|

| Part of a series on |

| Muisca culture |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History and timeline |

Muisca cuisine describes the food and preparation the Muisca elaborated. The Muisca were an advanced civilization inhabiting the central highlands of the Colombian Andes (Altiplano Cundiboyacense) before the Spanish conquest of the Muisca in the 1530s. Their diet and cuisine consisted of many endemic flora and fauna of Colombia.

The main product of the Muisca was maize, in various forms. The advantage of maize was that it could be grown in the various climatic zones the Muisca territories experienced.[1] It was the basis for their diet and the alcoholic drink, chicha, made from fermented maize and sugar.

In the Muisca religion their agriculture and celebration of harvests, conducted along the complex Muisca calendar, were protected by Chaquén and Nencatacoa. The Muisca ate a variety of roots and tubers and even had a specific word in their Chibcha language for eating those: bgysqua.[2]

Muisca cuisine

The Muisca cultivated many different crops in their own regions, part of the Muisca Confederation, and obtained more exotic culinary treats through trade with neighbouring indigenous peoples, with as most important; the Lache (cotton, tobacco, tropical fruits, sea snails), Muzo (emeralds, Magdalena River fish, access to gold, spices), Achagua (coca, feathers, yopó, Llanos Basin fish, curare).

The climatic variation of the Muisca territories allowed for the agriculture of different crops. Javier Ocampo López describes the Muisca diet as predominantly vegetarian: potatoes, maize, beans, mandioca, tomatoes, calabazas, peppers and numerous fruits. The Muisca also used grains known today as quinoa.

The main base for the Muisca cuisine was maize, considered a holy crop. The Muisca roasted corn (maize), ate it off the plant or converted it into popcorn.

Main meat was the guinea pig, endemic to South America, which they farmed in their homes. In special cases they ate llamas, alpacas, deer, capybara (chigüiro in Spanish), and fish from the rivers and lakes of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense and Magdalena and Llanos through trade. The Muisca drank a lot of chicha, a fermented alcoholic drink of maize and sugar, served in ceramic pots called urdu or aryballus.[3]

Paleodietary studies performed on the Bogotá savanna, where 18 Muisca skeletons ranging in historical age from 8th to 10th century AD and 26 skeletons from the 12th and 13th century AD, together with analysis of 10 mummies of the Guane, Lache and Muisca were analysed, have shown that about 60% of the food of the people consisted of vegetary products and 40% of meat and especially fish.

After the Spanish conquest, the access to meat was drastically reduced changing the diet of the Muisca and other indigenous groups of central Colombia. Studies from Tunja, called Hunza in the time of the Muisca, have shown the people did not suffer from malnutrition though.[4]

Words for maize

As maize was the most important crop and food for the Muisca, their language (Muysccubun) had many different words for maize, parts of the plant and the different processes and eating habits.[5]

| Muysccubun | English |

|---|---|

| aba | maize |

| abqui | corncob |

| abzie | maize hairs |

| fica | maize leaf |

| agua | maize kernels |

| amne | maize stem |

| abtiba | yellow maize |

| chiscami | black maize |

| fuquiepquijiza | white maize |

| fusuamuy | half-coloured maize |

| jachua | hard maize |

| jichuami | rice maize |

| pochuba | soft coloured maize |

| sasami | coloured maize |

| amtaquin | dry maize stem |

| amne chijuchua | green maize stem |

| absum | maize seed |

| abitago | maize surplus |

| abquy | grainless maize |

| bcahachysuca | removing maize grains |

| lie bun | maize roll |

| chochoca | seasoned maize |

Plants

_seeds.JPG.webp)

The Muisca cultivated their crops in so-called camellones, artificially elevated surfaces that allowed the roots of the crops to be sufficiently irrigated with the average 700-1000 mm of rain a year and drainage systems regulating the water levels.[6]

Main plants to be cultivated were:

- Canna edulis or achira, one of the first plants cultivated in the Andes[7]

- Arracacia xanthorrhiza or arracacha, ideally grown at altitudes of 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) and above, used in soups, grilled, boiled, fried or baked[8]

- Tropaeolum tuberosum, ideally grown at high altitudes exceeding 3,000 metres (9,800 ft)[9]

- Oxalis tuberosa—although this root is not native to Colombia, it was used by pre-Columbian societies in Cundinamarca and Boyacá, after being introduced from its place of origin in Peru, where the majority of varieties are found[10]

- Ullucus tuberosus or ulluco, used in various traditional dishes, still today[11]

- Yacón, eaten raw, usually with a bit of salt, also eaten traditionally today[12]

- Solanum tuberosum, Solanum colombianum, Solanum andigens, Solanum rybinii and Solanum boyacense, different types of potatoes were a lesser part of the Muisca diet; maize was more important[12]

- Manihot esculenta or yuca, a very important tuber in the diet of the South American indigenous people, cultivated as of 1120 BCE and still one of the most important ingredients in Colombian and other Latin-American cuisine[13]

- Ipomoea batatas, sweet potatoes, as evidenced from 3200 years before present in Zipacón[14]

Grains and cereals

- Zea mays or corn, earliest use of corn dated to 150 BCE in Zipaquirá, 275 BCE in Tequendama and even up to 2250 BCE[15]

- Chenopodium quinoa, quinoa, originating from Peru, more than 5000 years before present[16]

- Phaseolus vulgaris, common bean, first domesticated in Mexico, Central America, Peru and Colombia[17]

- Arachis hypogaea, peanuts, grown in the Andes and in Alto Magdalena[18]

- Erythrina edulis, called chachafruto or balú, growing at altitudes between 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) and 1,800 metres (5,900 ft)[18]

Fruits

- Inga feuilleei, where not the seeds yet the fruit was eaten[19]

- Curcubita maxima and Curcubita pepo, pumpkins, earliest evidence from Zipacón already 3860 BCE[20]

- Capsicum sp, such as C. pubescens, C. annuum, C. frutens, C. baccatum, peppers were common in the Americas and in Colombia, mainly product of trading with the U'wa (Tunebos)[21][22]

- Ananas comosus, pineapple, widely grown[23]

- Physalis peruviana or uchuva, typical fruit of Colombia, grown at altitudes above 2,200 metres (7,200 ft)[24]

- Solanum quitoense or lulo, the national fruit of Colombia[25]

- Passiflora, a wide variety of passionfruits,[26] such as P. mixta, P. cumablensis, P. antioquiensis and P. ambigua and the largest species P. quadrangularis[27]

- Persea americana or avocado[28]

- Psidium guajava, guava[29]

- Cyphomandra betacea, tree tomato[30]

- Annona cherimola, A. muricata and A. squamosal[31]

- Carica or papaya[32]

- Vaccinium meridionale[33]

- Rubus glaucus, R. macrocarpus and R. adenotrichus[34]

Leaves

- Galinsoga parviflora or guasca[35]

- Erythroxylum coca or coca[36]

Meat

Mammals

- Cavia porcellus, or guinea pig (guy), widely domesticated in Muisca territories[37]

- Odocoileus virginianus, Mazama rufina, M. americana and M. goazoubira, or species of deer[38]

- Cuniculus taczanowskii, or mountain paca[39]

- Armadillos[4]

- Capybara, traded with Achagua towards Llanos Orientales

Birds

As Colombia has the biggest biodiversity of birds in the world, they formed part of their cuisine, mainly:[40]

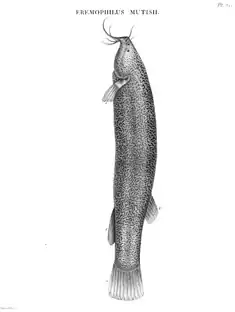

Fish

Insects

- Termites[42]

- Hormiga culona, a type of ant[42]

- Chisas, larvae of beetles[42]

- Worms[42]

- Cockroaches[42]

Food processing and preparation

Using the abundant coal of the Muisca territories, they heated their ovens and cooked their food.[43]

Eating habits

The Muisca sat down on the ground while eating and they did not use cutlery, and ate with their hands. The food was served on leaves or in ceramic pots.[43]

See also

References

- ↑ Restrepo, 2009, p.29

- ↑ García, 2012, p.65

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.177

- 1 2 Martínez & Manrique, 2014, p.100

- ↑ Daza, 2013, pp.27-28

- ↑ García, 2012, p.43

- ↑ García, 2012, p.44

- ↑ García, 2012, p.50

- ↑ García, 2012, p.52

- ↑ García, 2012, p.55

- ↑ García, 2012, p.56

- 1 2 García, 2012, p.59

- ↑ García, 2012, p.61

- ↑ García, 2012, p.63

- ↑ García, 2012, p.66

- ↑ García, 2012, p.73

- ↑ García, 2012, p.76

- 1 2 García, 2012, p.80

- ↑ García, 2012, p.82

- ↑ García, 2012, p.84

- ↑ García, 2012, p.87

- ↑ Rodríguez Cuenca, 2006, p.115

- ↑ García, 2012, p.90

- ↑ García, 2012, p.91

- ↑ García, 2012, p.93

- ↑ García, 2012, p.94

- ↑ García, 2012, p.98

- ↑ García, 2012, p.100

- ↑ García, 2012, p.103

- ↑ García, 2012, p.105

- ↑ García, 2012, p.106

- ↑ García, 2012, p.109

- ↑ García, 2012, p.110

- ↑ García, 2012, p.112

- ↑ García, 2012, p.115

- ↑ García, 2012, p.116

- ↑ García, 2012, p.122

- ↑ García, 2012, p.127

- ↑ Cardale, 1985, p.105

- ↑ García, 2012, p.132

- ↑ García, 2012, p.133

- 1 2 3 4 5 Restrepo, 2009, p.41

- 1 2 Restrepo, 2009, p.43

Bibliography

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. En busca de los primeros agricultores del Altiplano Cundiboyacense - Searching for the first farmers of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 99–125. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Daza, Blanca Ysabel. 2013. Historia del proceso de mestizaje alimentario entre Colombia y España - History of the integration process of foods between Colombia and Spain (PhD), 1-494. Universitat de Barcelona.

- García, Jorge Luis. 2012. The Foods and crops of the Muisca: a dietary reconstruction of the intermediate chiefdoms of Bogotá (Bacatá) and Tunja (Hunza), Colombia (M.A.), 1–201. University of Central Florida. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Martínez Martín, A. F., and E. J. Manrique Corredor. 2014. Alimentación prehispánica y transformaciones tras la conquista europea del altiplano cundiboyacense, Colombia. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte 41. 96–111. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América - Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Restrepo Manrique, Cecilia. 2009. La alimentación en la vida cotidiana del Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario: 1653-1773 & 1776-1900 - The food in the daily life of the Colegio Mayor de Nuestra Señora del Rosario: 1653-1773 & 1776-1900, 1–352. Ministerio de la Cultura. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Rodríguez Cuenca, José Vicente. 2006. Las enfermedades en las condiciones de vida prehispánica de Colombia - La alimentación prehispánica - The diseases in the prehispanic living conditions of Colombia - the prehispanic food, 83–128. Accessed 2016-07-08.