| Moti Masjid (Red Fort) | |

|---|---|

Exterior view of the Pearl Mosque (Moti Masjid) of the Red Fort | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| District | Central Delhi |

| Governing body | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Status | Inactive |

| Location | |

| Location | Delhi |

| Country | India |

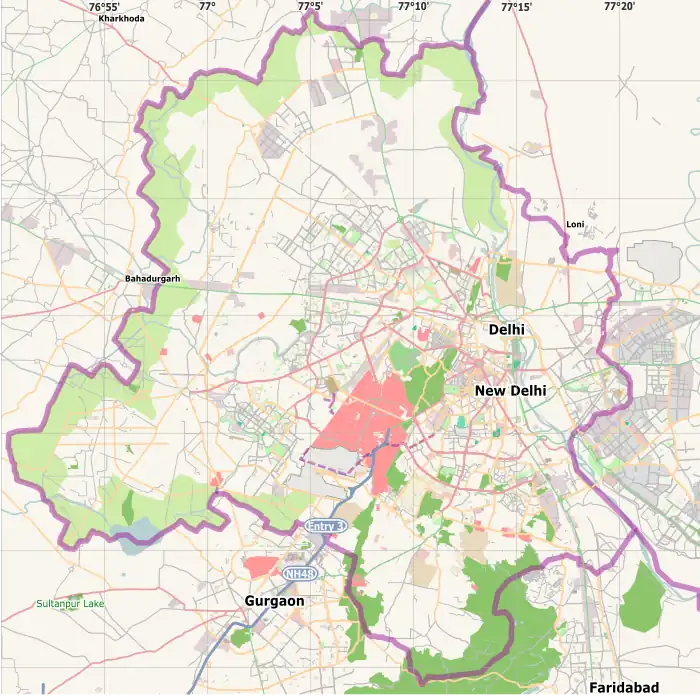

Shown within Delhi  Moti Masjid (Red Fort) (India) | |

| Territory | Delhi |

| Geographic coordinates | 28°39′25″N 77°14′35″E / 28.656815°N 77.243142°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Mughal |

| Founder | Aurangzeb |

| Completed | 1663 |

| Construction cost | 1 lakh and 60 thousand rupees |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Site area | 9 by 15 metres |

| Materials | White marble, red sandstone |

The Moti Masjid (lit. 'Pearl mosque')[1] is a 17th-century mosque inside the Red Fort complex in Delhi, India. It was built by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, damaged by the Siege of Delhi, and subsequently restored by the British. Named for its white marble,[2] the mosque features ornate floral carvings. It is an important example of Mughal architecture during Aurangzeb's reign.

History

The Moti Masjid was commissioned by Mughal emperor Aurangzeb shortly after his accession. The purpose was to provide the emperor a mosque for prayer closer to his private chambers within the Red Fort. At the time, the fort did not contain a mosque; the fort's builder and previous occupant, emperor Shah Jahan, instead offered congregational prayers at the nearby Jama Masjid.[3] Construction of the Moti Masjid took five years, completing in the year 1663, at the emperor's personal expense; the court chronicle Ma'asir-i-Alamgiri describes the cost to be 1 lakh and 60 thousand rupees.[3][4][5] Following its construction, Aurangzeb began to offer the zuhr prayer at the mosque with officials of the state, introducing a new ceremonial practice.[5]

In 1857, British soldiers looted the Red Fort, following its capture in the Siege of Delhi. The Moti Masjid in particular had its gilded copper domes stripped by Prize Agents (British military who had been authorized to collect spoils) and sold by auction. This exposed the domes to the elements, causing them to deteriorate, and allowed rainwater to damage the ceiling of the prayer hall.[6] The mosque domes were later replaced by the British with those of white marble.[3][2]

In the 1920s, initiatives by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) led to a swelling of tourism at the Red Fort, and the Moti Masjid experienced increased foot traffic. This caused rules and regulations to be put in place so as to have visitors comply with Islamic conduct. In the post-Revolt era, the ASI also raised concerns over British military personnel damaging the marble floors of the mosque.[7]

In the modern era, the ASI has kept the mosque building closed to visitors, to avoid damage to the structure.[8]

Architecture

The Moti Masjid consists of a prayer hall and courtyard, contained in a walled enclosure. The site is small, internally measuring 9 by 15 metres. The compound is raised slightly above ground level and entered from the east, accessed by a staircase. The enclosure walls are made of red sandstone, and are of notable height, obstructing the view of the structures within. The walls also vary in thickness, compensating for the mosque's orientation - the exterior walls align with the axes of the Red Fort, while the interior walls are aligned towards Mecca, as per Islamic tradition. The courtyard of the mosque is rectangular, and contains a recessed pool.[3][9][2]

Set at the end of the courtyard is the prayer hall (the main mosque building), a three-bayed structure divided into two aisles. The structure also has corridors for use by the ladies of the court. The facade of the prayer hall features three entrance arches on piers, as well as a curvilinear eave (bangla chhajja). The mosque building is topped by three pointed domes, sitting on constricted necks, aligned with the arches in the facade.[3][9] The prayer hall's marble floor is demarcated into rectangles, possibly to mark positions for worshippers.[2]

The Moti Masjid most closely resembles the Nagina Masjid, another small-scale palace mosque, built by Aurangzeb's predecessor Shah Jahan in the Agra Fort. Scholar Ebba Koch goes as far as to call it a near-literal copy. Both monuments have a similar plan, elevation, and building material (white marble). However, the Moti Masjid departs from the Nagina Masjid, in its extensive use of ornamentation. Unlike the Nagina Masjid, whose surfaces are plain, the Moti Masjid features a program of ornate floral decoration, executed as marble reliefs and inlays. These are found on the mosque's walls, arches, piers, and pendentives. Particularly notable are the mihrab (prayer niche) of the mosque, which features vine motifs, and the minbar (pulpit), sculpted as an acanthus vine supporting three steps. Such ornamentation stems from the palace architecture of Shah Jahan, reflected in several pavilions of the Red Fort. This is notably contrasted with the religious buildings of Shah Jahan's reign, which were more austere in nature. Dadlani views this as an innovation of Aurangzeb's reign, which also appears on his later imperial mosques. The Moti Masjid is also innovative in what Asher terms its 'spatial tension', achieved by the height of its enclosure walls and its domes; this spatial tension would become a feature of architecture during Aurangzeb's reign.[10][3][4]

Koch notes that the ostentatious design of the mosque stands in contrast to Aurangzeb's reputation of artistic austerity. She argues that this indicates the emperor's lack of direct involvement in the stylism of the project.[4] On the other hand, Dadlani views the monument as part of Aurangzeb's 'imperial visual program', which emphasized the construction of mosques to portray himself as a pious ruler, but also used ornamentation to recall Shah Jahan's reign, and thereby its political stability.[11]

Gallery

Bronze main door with floral decoration

Bronze main door with floral decoration.jpg.webp) Interior of the mosque, with ornate carvings on marble surfaces

Interior of the mosque, with ornate carvings on marble surfaces Samuel Bourne, "The Motee Musjid. Delhi. 1351," 1863–1869, photograph mounted on cardboard sheet, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC.

Samuel Bourne, "The Motee Musjid. Delhi. 1351," 1863–1869, photograph mounted on cardboard sheet, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Art Library, Washington, DC. Courtyard of the mosque, containing a recessed pool

Courtyard of the mosque, containing a recessed pool

References

- ↑ Dadlani 2019, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Alfieri, Bianca Maria (2000). Islamic Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Lawrence King Publishing. p. 267. ISBN 9781856691895.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Asher, Catherine B. (24 September 1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 255–257. doi:10.1017/chol9780521267281. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.

- 1 2 3 Koch, Ebba (1991). Mughal architecture : an outline of its history and development, 1526-1858. München, Federal Republic of Germany: Prestel. pp. 129–131. ISBN 3-7913-1070-4. OCLC 26808918.

- 1 2 Dadlani 2019, p. 37-38.

- ↑ Rajagopalan, Mrinalini (2016). Building Histories: The Archival and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern Delhi. University of Chicago Press. pp. 41, 49. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226331898.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-28347-0.

- ↑ Rajagopalan, Mrinalini (2016). Building Histories: The Archival and Affective Lives of Five Monuments in Modern Delhi. University of Chicago Press. pp. 52 & 107. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226331898.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-28347-0.

- ↑ Soofi, Mayank Austen (3 July 2017). "Delhiwale: Monument for a vilified emperor". Hindustan Times. New Delhi.

- 1 2 Dadlani 2019, p. 9.

- ↑ Dadlani 2019, p. 9-14.

- ↑ Dadlani 2019, p. 38-39.

Bibliography

- Dadlani, Chanchal B. (12 August 2019), "Chapter 1: Between Experimentation and Regulation: The Foundations of an Eighteenth-Century Style", From Stone to Paper: Architecture as History in the Late Mughal Empire, Yale University Press, doi:10.37862/aaeportal.00054.005, ISBN 978-0-300-25096-1, retrieved 2 December 2023