Minefields in Croatia cover 258.00 square kilometres (99.61 square miles) of territory.[1] As of 2020, the minefields (usually known as "mine suspected areas") are located in 45[1] cities and municipalities within 8[1] counties. These areas are thought to contain approximately 17,285[1] land mines, in addition to unexploded ordnance left over from the Croatian War of Independence. Land mines were used extensively during the war by all sides in the conflict; about 1.5 million were deployed. They were intended to strengthen defensive positions lacking sufficient weapons or manpower, but played a limited role in the fighting.

After the war 13,000 square kilometres (5,000 square miles) of territory was initially suspected to contain mines, but this estimate was later reduced to 1,174 square kilometres (453 square miles) after physical inspection. As of 2013 demining programs were coordinated through governmental bodies such as the Croatian Mine Action Centre, which was hiring private demining companies employing 632 deminers. The areas are marked with 11,454[1] warning signs.

As of 4 April 2013, 509 people had been killed and 1,466 injured by land mines in Croatia since the war; with these figures including 60 deminers and seven Croatian Army engineers killed during demining operations. In the immediate aftermath of the war, there were about 100 civilian mine casualties per year, but this decreased to below ten per year by 2010 through demining, mine-awareness, and education programs. Croatia has spent approximately €450 million on demining since 1998, when the process was taken over by private contractors coordinated by the Croatian Mine Action Centre. The cost to complete the demining is estimated at €500 million or more. Economic loss to Croatia (due to loss of land use within suspected minefields) is estimated at €47.3 million per year.

Background

In 1990, following the electoral defeat of the Communist regime in Croatia by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), ethnic tensions between Croats and Serbs worsened. After the elections, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) confiscated Croatia's Territorial Defence weapons to minimize potential resistance.[2] On 17 August, tensions escalated to an open revolt by the Croatian Serbs. The JNA stepped in, preventing Croatian police from intervening.[3] The revolt centred on the predominantly Serb-populated areas of the Dalmatian hinterland around the city of Knin,[4] parts of the Lika, Kordun and Banovina regions and eastern Croatian settlements with a significant Serb population.[5] This incontiguous area was subsequently named the Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK). The RSK declared its intention to join Serbia, and as a result came to be viewed by the Government of Croatia as a breakaway region.[6] By March 1991, the conflict had escalated into what became known as the Croatian War of Independence.[7] In June, Croatia declared its independence as Yugoslavia disintegrated.[8] By January 1992, the RSK held 17,028 square kilometres (6,575 sq mi) of territory within borders claimed by Croatia. This territory ranged from 2.5 to 63.1 kilometres (1.6 to 39.2 miles) in depth, and had a 923-kilometre (574 mi) front line along Croatian-controlled territory.[9]

Wartime use

.jpg.webp)

Land mines were first used by the JNA in early 1991, before its withdrawal from Croatia, to protect military barracks and other facilities. Even JNA facilities located in urban centers were secured in this way, using mines such as the PROM-1 bounding mine and MRUD directional anti-personnel mine.[10] The Croatian Army (HV) and Croatian police began laying land mines in late 1991, relying heavily on them to stop advances by the JNA and the Army of the RSK (ARSK) until early 1992. These early minefields were laid with little documentation. In 1992 the ARSK increased its use of mines to secure the front line,[11] largely due to its limited number of troops. Consequently, the ARSK constructed static defensive lines (consisting of trenches, bunkers and large numbers of mines designed to protect thinly-manned defences) to delay HV offensives. This approach was necessitated by the limited depth of RSK territory and the lack of reserves available with which to counterattack (or block) breaches of its defensive line, which meant that the ARSK was unable to employ defence in depth tactics.[12] The combination of poor documentation of minefield locations and the lack of markings (or fencing) led to frequent injuries to military personnel caused by mines laid by friendly forces.[13] It is estimated that a total of 1.5 million land mines were laid during the war.[10]

The HV successfully used anti-tank mines as obstacles in combination with infantry anti-tank weapons, destroying or disabling more than 300 JNA tanks (particularly during defensive operations in Slavonia).[10] Conversely, anti-personnel mines deployed by the ARSK proved less effective against the HV during operations Flash and Storm in 1995. During these operations, the HV crossed (or bypassed) many ARSK minefields based on information from land-based and unmanned aerial vehicle reconnaissance of the movement of ARSK patrols, civilian populations, and the activation of mines by wildlife.[14] Out of the 224 HV personnel killed in operations Flash and Storm, only 15 fatalities were caused by land mines. Similarly, out of 966 wounded in the two offensives only 92 were injured by land mines.[15]

Casualties

As of 4 April 2013 a total of 509 people had been killed and 1,466 injured by land mines in 1,352 incidents in Croatia.[16] There were 557 civilian casualties from land mines between 1991 and 1995, during the war and in its immediate aftermath. Between 1996 and 1998 there were approximately 100 civilian casualties from land mines per year in Croatia,[17] but the number gradually decreased to less than ten per year by 2010.[18] During the war, 57 HV troops were killed or injured by mines in 1992.[19] In 1995, 169 were killed or injured (most during operations Flash and Storm)[15] out of 130,000 HV troops involved.[20] Seven HV engineers were killed and 18 injured by land mines during HV mine clearance operations between 1996 and 1998.[17] Civilian casualties include 60 deminers killed since 1998.[21]

Croatia has established an extensive framework to assist those injured by mines and the families of mine victims. This assistance includes emergency and ongoing medical care, physical rehabilitation, psychological and social support, employment and social-integration assistance, public awareness, and access to public services. Institutions and organizations supporting mine victims include a wide range of governmental bodies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).[22]

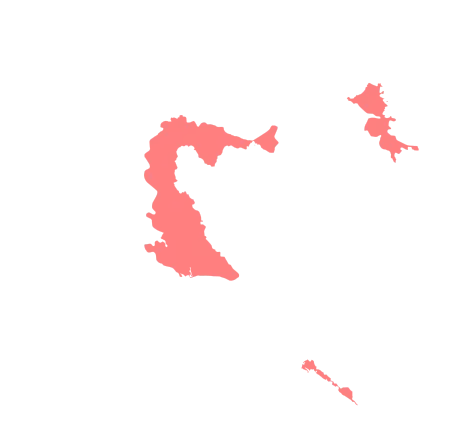

Existing minefields

As of November 2022, minefields in Croatia cover 149.7 square kilometres (57.8 square miles) of territory. The minefields (usually known as "mine suspected areas" or MSA) are located in 6 counties and 28 cities and municipalities. These areas are thought to contain approximately c.11,732 land mines, in addition to unexploded ordnance left over from the Croatian War of Independence.[23][24]

The area suspected of containing land mines is marked using more than 6,255 warning signs. Based on the analysis of the area structure in MSAs, at the end of 2022, after the demining, technical survey and general and supplementary general survey, it was determined that 98.7% of MSAs are forests and forest areas, while 1.2% MSAs of the Republic of Croatia are agricultural land, and 0.1% of MSAs are categorized as "other areas" (water, wetlands, rocks, landslides, rocks, shores, etc.).[25][26]

In 2023, areas thought to contain unexploded ordnance (but no land mines) had been marked with 6,255 warning signs.[18]

| County | 1 January 2022 | 1 January 2023 | Demining plan in 2023 | Demining plan in 2024 | Demining plan in 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bjelovar-Bilogora | Demined in 2005[27] | ||||

| Brod-Posavina | Demined in 2018[28] | ||||

| Dubrovnik-Neretva | Demined in 2014[27][29] | ||||

| Karlovac | 38.1 (14.7) | 18.9 (7.3) | −11.5 (−4.4) | −7.0 (−2.7) | To be demined |

| Lika-Senj | 86.7 (33.5) | 74.6 (28.8) | −17.4 (−6.7) | −24.4 (−9.4) | −31.3 (−12.1) |

| Osijek-Baranja | 11.1 (4.3) | 6.8 (2.6) | −7.1 (−2.7) | To be demined | |

| Požega-Slavonia | Demined in 2022[30] | ||||

| Sisak-Moslavina | 34.8 (13.4) | 25.0 (9.7) | −9.5 (−3.7) | −11.1 (−4.3) | −5.5 (−2.1) |

| Split-Dalmatia | 18.1 (7.0) | 16.5 (6.4) | −7.1 (−2.7) | −8.6 (−3.3) | To be demined |

| Šibenik-Knin | Demined in 2023[31] | ||||

| Virovitica-Podravina | Demined in 2014[27] | ||||

| Vukovar-Syrmia | Demined in 2016[27][32] | ||||

| Zadar | Demined in 2021[24] | ||||

| Zagreb | Demined in 2005[27] | ||||

| Total | 239.4 (92.4) | 149.7 (57.8) | −60.6 (−23.4) | −51.1 (−19.7) | −36.8 (−14.2) |

Social and economic impacts

Land mines are a safety issue for populations living near minefields. In 2008, an estimated 920,000 people in Croatia were endangered by their proximity to mined areas (20.8 percent of the population). Land mines are also a significant problem for development, because a substantial portion of the minefields in Croatia are on agricultural land and in forests. Some drainage channels are consequently inaccessible for maintenance, resulting in intermittent flooding; this is particularly severe in areas bordering Hungary. Similar problems are caused by mines laid on the banks of the Drava, Kupa, and Sava rivers.[33] The presence of land mines adversely affected post-war recovery in rural areas, reducing the amount of available agricultural land, impeding development, and affecting the quality of life for people in mined areas.[34] In addition to agriculture, the most significant economic problem caused by mines in Croatia is their impact on tourism (especially on forested areas and hunting in areas inland from the Adriatic Sea coast). In 2012, it was estimated that the economy of Croatia lost 355 million kuna (c. 47.3 million euros) a year from the effects of mine-suspected areas on the economy.[35]

Because of the importance of tourism to the Croatian economy, areas frequented by tourists (or near major tourist routes) have been given priority for demining.[33] Other safety-related areas receiving demining priority are settlements, commercial and industrial facilities and all documented minefields. Agricultural land, infrastructure, and forests are grouped in three priority categories depending on their economic significance. National parks in Croatia were also demined as top-priority areas, along with areas significant for fire protection.[36] Theft of minefield signs is a significant problem, and is particularly pronounced in areas with concerns among the local population that the signs harm tourism. The signs are regularly replaced, sometimes with concrete or masonry structures to display them instead of metal poles.[37] Since the 1990s, only one tourist has been injured by a land mine in Croatia.

The Government of Croatia established several bodies to address the problem of land mines in Croatia; foremost among them are the Office for Mine Action and the Croatian Mine Action Centre. The Office for Mine Action is a government agency tasked with providing expert analysis and advice on demining. The Croatian Mine Action Centre is a public-sector body tasked with planning and conducting demining surveys, accepting cleared areas, marking mine-suspected areas, quality assurance, demining research and development, and victim assistance. The work of the Croatian Mine Action Centre is supervised by the Office for Mine Action.[38][39]

As refugees flee to Europe, from Syria and other Middle Eastern nations, some are migrating through Croatia due to Hungary's recent closing of its borders. These immigrants trying to cross to Europe are seeking Croatia's help in finding safe routes of passage.

Mine awareness and education

Croatia has implemented a mine-awareness educational program aimed at reducing the frequency of mine-related accidents through an ongoing information campaign. The program is conducted by the Croatian Red Cross, the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports and several NGOs in cooperation with the Croatian Mine Action Centre. The Croatian Mine Action Centre actively supports NGOs to develop as many programs as possible and attract new NGOs to mine-awareness and educational activities.[40] It maintains an accessible online database with cartographic information on the location of mine-suspected areas in Croatia.[41]

One mine-awareness campaign involving billboard advertising attracted criticism from the Ministry of Tourism and the Croatian National Tourist Board (CNTB) because the signs were placed in tourist areas, far from any mine-suspected areas. The Ministry of Tourism and the CNTB welcomed the effort's humanitarian aspect, but considered the signs a potential source of unwarranted negative reaction from tourists.[42] Tourist guidebooks of Croatia include warnings about the danger posed by mines in the country, and provide general information about their location.[43]

Demining

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the Croatian War of Independence, approximately 13,000 square kilometres (5,000 square miles) of the country was suspected of containing land mines.[44] During the war and in its immediate aftermath, demining was performed by HV engineers[17] supported by police and civil defence personnel. Wartime demining was focused on clearance tasks in support of military operations and the safety of the civilian population. In 1996 the Parliament of Croatia enacted the Demining Act, tasking police with its organization and the government-owned AKD Mungos company with the demining itself.[45] By April 1998 approximately 40 square kilometres (15 square miles) had been cleared of mines, and the initial estimate of minefield areas was reduced after inspection. By 2003 the entire territory of Croatia was reviewed, and the minefield area was reduced to 1,174 square kilometres (453 square miles).[46]

Since May 1998[47] the Croatian Mine Action Centre has been tasked with the development of demining plans, projects, technical inspections, cleared-area handover, demining quality assurance, expert assistance and the coordination of mine-clearance activities.[39] The demining is performed by 35 licensed companies, employing 632 demining professionals and 58 auxiliary personnel. The companies do their work with 681 metal detectors, 55 mine rollers and mine flails, and 15 mine-detection dogs.[48] Mine-clearing machines include locally designed models produced by DOK-ING.[49] Deminers typically earn €.50–1.20 for each 1 square metre (11 square feet) cleared, or €800–900 a month.[50]

Since 1998, demining has been funded through the government and by donations. From 1998 to 2011, donations amounted to €75.5 million (17 percent of the total of €450 million spent on demining during that period). Most donations were from foreign contributors, including NGOs and foreign governments (among them Japan, Germany, Monaco, Luxembourg and the United States). The European Union was also a significant contributor during that period, providing €20.7 million.[51] As of 2013, the Croatian Mine Action Centre has been allocated approximately 400 million kuna (c. 53 million euros) a year for demining.[49] In 2011, an estimated further €500 million (or more) was needed to remove all remaining land mines from Croatia by 2019,[52] the deadline for land-mine clearance set by the Ottawa Treaty.[53] The Croatian Mine Action Centre spends approximately 500,000 kuna (c. 66,600 euros) a year to maintain minefield warning signs (including the replacement of stolen signs).[44]

As of April 2017, approximately 446 km² containing around 43,000 potential landmines was yet to be cleared.[54]

On July 28, 2022, the Croatian government submitted to the Parliament the Proposal for the National Mine Action Program until 2026, which defines the demining strategy for mine-suspected areas and the deadline for completion by county.[55]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Minska situacija u RH". civilna-zastita.gov.hr. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ Hoare 2010, p. 117

- ↑ Hoare 2010, p. 118

- ↑ The New York Times & 19 August 1990

- ↑ ICTY & 12 June 2007

- ↑ The New York Times & 2 April 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 3 March 1991

- ↑ The New York Times & 26 June 1991

- ↑ Marijan 2007, p. 36

- 1 2 3 Halužan 1999, p. 142

- ↑ Halužan 1999, p. 143

- ↑ Balkan Battlegrounds 2002, p. 272

- ↑ Halužan 1999, p. 144

- ↑ Halužan 1999, p. 147

- 1 2 Halužan 1999, p. 148

- ↑ tportal.hr & 4 April 2013

- 1 2 3 Halužan 1999, p. 149

- 1 2 HCR 2010, p. 8

- ↑ Halužan 1999, p. 145

- ↑ Index.hr & 5 August 2011

- ↑ Slobodna Dalmacija & 24 July 2012

- ↑ HCR & Assistance

- ↑ "Minska situacija u RH" [Mine situation in Croatia]. Ravnateljstvo civilne zaštite (in Croatian). Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- 1 2 "Svečano obilježen završetak razminiranja Zadarske županije" [The demining of the Zadar County was solemnly marked]. Ministarstvo unuratnjih poslova (in Croatian). 17 December 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- 1 2 "Izvješće o provedbi plana protuminskog djelovanja i utrošenim financijskim sredstvima za 2022. godinu" [Report on the implementation of the mine action plan and the financial resources spent for 2022] (PDF). Hrvatski sabor (in Croatian). Croatian Government. 4 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- 1 2 "Prijedlog nacionalnog programa protuminskog djelovanja Republike Hrvatske do 2026. godine" [Proposal of the national mine action program of the Republic of Croatia until 2026] (PDF). Hrvatski Sabor. Zagreb. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mjesec zaštite od mina: U Hrvatskoj još uvijek veliki broj zaostalih eksplozija iz rata" [Mine Protection Month: Croatia still has a large backlog of war explosions]. Hrvatski crveni križ (in Croatian). 4 April 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ↑ "Brodsko-posavska županija slobodna od mina: Pronađeno i uništeno 1700 komada eksplozivnih ostataka rata" [Brod-Posavina County free of mines: 1,700 explosive remnants of war found and destroyed]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 11 June 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ↑ Miličić Vukosavić, Nila (28 June 2014). "Dubrovačko-neretvanska županija očišćena od mina" [Dubrovnik-Neretva County cleared of mines]. HRT (in Croatian). Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ↑ Pejaković, Mateo (21 November 2022). "Požeško-slavonska županija je od danas i službeno bez mina" [As of today, Požega-Slavonia County is officially mine-free]. požeški.hr (in Croatian). Retrieved 21 November 2022.

- ↑ Petrić, Ana (4 December 2023). "Završio 'rat' nakon rata: Šibensko- kninska županija konačno razminirana, očišćena od podmuklog oružja" [Ended the 'war' after the war: Šibenik-Knin County finally demined, cleared of insidious weapons]. šibenski. (in Croatian). Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ "Vukovarsko-srijemska županija u cijelosti očišćena od mina" [Vukovar-Srijem County completely cleared of mines]. Vukovarsko-srijemska županija (in Croatian). 17 February 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- 1 2 HCR & Programme, p. 6

- ↑ MVEP 2008, p. 8

- ↑ tportal.hr & 21 November 2012

- ↑ HCR & Programme, p. 7

- ↑ ezadar.hr & 28 August 2011

- ↑ Vlada RH & 22 May 2012

- 1 2 HCR & Activities

- ↑ HCR & Programme, p. 4

- ↑ HCR & Awareness

- ↑ MT & 23 February 2006

- ↑ Bousfield 2003, p. 47

- 1 2 Večernji list & 7 March 2012

- ↑ HCR & Programme, p. 1

- ↑ HCR & Programme, p. 2

- ↑ "Do 2026. razminirati 277,63 četvorna kilometra šuma". Glas Slavonije. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ↑ HCR & Licensees

- 1 2 Index.hr & 4 April 2013

- ↑ DW & 4 April 2013

- ↑ HCR & Donations

- ↑ tportal.hr & 7 September 2011

- ↑ Nacional & 14 January 2011

- ↑ Igor Spaic (4 April 2017). "Bosnia 'Failing to Meet Landmine Removal Target'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ "Prijedlog nacionalnog programa protuminskog djelovanja do 2026. godine" [Proposal for the National Mine Action Program until 2026] (PDF). Hrvatski Sabor (in Croatian). Zagreb. 28 July 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

References

- Books

- Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990–1995. Darby, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing Company. 2003. ISBN 978-0-7567-2930-1.

- Bousfield, Jonathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Croatia. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-084-8.

- Hoare, Marko Attila (2010). "The War of Yugoslav Succession". In Ramet, Sabrina P. (ed.). Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Marijan, Davor (2007). Oluja [Storm] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Memorial-Documentation Centre of the Homeland War of the Government of Croatia. ISBN 978-953-7439-08-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- News reports

- Alač, Zvonko (5 August 2011). "Oluja: 16 godina od hrvatskog rušenja Velike Srbije" [Storm: 16 years since Croatia toppled Greater Serbia] (in Croatian). Index.hr. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013.

- Bogdanić, Siniša; Arbutina, Zoran (4 April 2013). "Croatia brings minefields to EU soil". Deutsche Welle.

- "Donacija od više milijuna dolara: Bill Gates pomaže razminiravanju Hrvatske" [Multi-million-dollar donation: Bill Gates supports demining in Croatia] (in Croatian). Nacional. 14 January 2011. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- Dukić, Snježana (24 July 2012). "Pirotehničare tjeraju u smrt za 2,5 kune" [Deminers led to death for 2.5 kuna]. Slobodna Dalmacija (in Croatian).

- Engelberg, Stephen (3 March 1991). "Belgrade Sends Troops to Croatia Town". The New York Times.

- Flauder, Goran (7 September 2011). "Za razminiranje Hrvatske trebat će više od pola milijarde eura" [It will take more than a half a billion euro to clear mines from Croatia] (in Croatian). tportal.hr.

- "Kako mine koče hrvatsko gospodarstvo?" [How do mines impede Croatian development?] (in Croatian). tportal.hr.

- Luić, Andrina. "U okolici Zadra ukradeno 200 ploča koje upozoravaju na mine" [200 mine warning signs stolen in Zadar area]. Večernji list (in Croatian).

- "Milanović: Nisam zadovoljan proračunom za razminiranje; Bandić: Hrvatski stroj za razminiranje je naš ponos!" [Milanović: I am not satisfied with demining budget; Bandić: Croatian demining machine is our pride!] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 4 April 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013.

- "Policija: Nizozemski turist stradao u eksploziji protupješadijske mine, tzv. paštete" [Police: A Dutch tourist injured in an anti-personnel land mine explosion] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 21 July 2005.

- "Političari pokazali čarape u humanitarne svrhe" [Politicians show socks in support of a humanitarian cause] (in Croatian). tportal.hr. 4 April 2013.

- "Roads Sealed as Yugoslav Unrest Mounts". The New York Times. Reuters. 19 August 1990.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 April 1991). "Rebel Serbs Complicate Rift on Yugoslav Unity". The New York Times.

- "Uklanjaju upozorenja o minama da im ne otjeraju goste?!" [Removing mine warnings not to drive their guests away?!] (in Croatian). ezadar.hr. 28 August 2011.

- Other sources

- "Croatian Tourism: Great Results in First Two Months". Ministry of Tourism (Croatia). 23 February 2006.

- "Donacije" [Donations] (in Croatian). Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- "Introduction". Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original on 2019-01-10. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Izviješće o provedbi plana humanitarnog razminiravanja i utrošenim financijskim sredstvima za 2010. godinu" [Report on implementation of humanitarian demining plan and spent financial assets in 2010] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-18. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Kapaciteti ovlaštenih pravnih osoba" [Resources of licensed legal persons] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Mine Action Centre. 16 April 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013.

- Halužan, Slavko (December 1999). "Vojna učinkovitost protupješačkih mina: Iskustva iz Domovinskog rata" [Military effectiveness of anti-personnel land mines: Experience from the Croatian War of Independence]. Polemos: Journal of Interdisciplinary Research on War and Peace (in Croatian). Croatian Sociological Association. 2 (3–4). ISSN 1331-5595.

- "Mine Action in Croatia". Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Mine Risk Education and Mine Awareness". Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Mine victims assistance (MVA)". Croatian Mine Action Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Minska situacija u RH - srpanj 2014" [Mine situation in the Republic of Croatia - July 2014] (in Croatian). Office for Mine Action of the Government of Croatia. Archived from the original on 2013-12-29.

- "Nacionalni program protuminskog djelovanja - sažetak" [National programme of counter-mine activities - summary] (PDF) (in Croatian). Croatian Mine Action Centre. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-05. Retrieved 2013-04-18.

- "Pregovaračko stajalište Republike Hrvatske za Međuvladinu konferenciju o pristupanju Republike Hrvatske Europskoj uniji za poglavlje 11. "Poljoprivreda i ruralni razvitak"" [Negotiation platform of the Republic of Croatia for the Intergovernmental conference on accession of the Republic of Croatia to the European Union for chapter 11 "Agriculture and rural development"] (PDF) (in Croatian). Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (Croatia). 4 September 2008.

- "The Prosecutor vs. Milan Martic - Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 12 June 2007.

- "Ured za razminiranje" [Office for Demining] (in Croatian). Government of Croatia. 22 May 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013.