| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

β-D-Galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-D-glucose | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R,3R,4S,5R,6S)-2-(Hydroxymethyl)-6-{[(2R,3S,4R,5R,6R)-4,5,6-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-3-yl]oxy}oxane-3,4,5-triol | |

| Other names

Milk sugar Lactobiose 4-O-β-D-Galactopyranosyl-D-glucose | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 90841 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.509 |

| EC Number |

|

| 342369 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H22O11 | |

| Molar mass | 342.297 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Density | 1.525 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 252 °C (anhydrous)[1] 202 °C (monohydrate)[1] |

| 195 g/L[2][3] | |

Chiral rotation ([α]D) |

+55.4° (anhydrous) +52.3° (monohydrate) |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

5652 kJ/mol, 1351 kcal/mol, 16.5 kJ/g, 3.94 kcal/g |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | 357.8 °C (676.0 °F; 631.0 K)[4] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Lactose, or milk sugar, is a disaccharide sugar synthesized by galactose and glucose subunits and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from lact (gen. lactis), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix -ose used to name sugars. The compound is a white, water-soluble, non-hygroscopic solid with a mildly sweet taste. It is used in the food industry.[5]

Structure and reactions

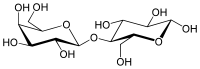

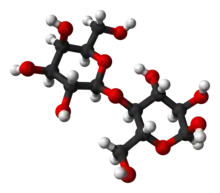

Lactose is a disaccharide derived from the condensation of galactose and glucose, which form a β-1→4 glycosidic linkage. Its systematic name is β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1→4)-D-glucose. The glucose can be in either the α-pyranose form or the β-pyranose form, whereas the galactose can only have the β-pyranose form: hence α-lactose and β-lactose refer to the anomeric form of the glucopyranose ring alone. Detection reactions for lactose are the Woehlk-[6] and Fearon's test.[7] Both can be easily used in school experiments to visualise the different lactose content of different dairy products such as whole milk, lactose free milk, yogurt, buttermilk, coffee creamer, sour cream, kefir, etc.[8]

Lactose is hydrolysed to glucose and galactose, isomerised in alkaline solution to lactulose, and catalytically hydrogenated to the corresponding polyhydric alcohol, lactitol.[9] Lactulose is a commercial product, used for treatment of constipation.

Occurrence and isolation

Lactose comprises about 2–8% of milk by weight. Several million tons are produced annually as a by-product of the dairy industry.

Whey or milk plasma is the liquid remaining after milk is curdled and strained, for example in the production of cheese. Whey is made up of 6.5% solids, of which 4.8% is lactose, which is purified by crystallisation.[10] Industrially, lactose is produced from whey permeate – that is whey filtrated for all major proteins. The protein fraction is used in infant nutrition and sports nutrition while the permeate can be evaporated to 60–65% solids and crystallized while cooling.[11] Lactose can also be isolated by dilution of whey with ethanol.[12]

Dairy products such as yogurt and cheese contain very little lactose. This is because the bacteria used to make these products breaks down lactose through the use of lactase.

Metabolism

Infant mammals nurse on their mothers to drink milk, which is rich in lactose. The intestinal villi secrete the enzyme lactase (β-D-galactosidase) to digest it. This enzyme cleaves the lactose molecule into its two subunits, the simple sugars glucose and galactose, which can be absorbed. Since lactose occurs mostly in milk, in most mammals, the production of lactase gradually decreases with maturity due to genetic predispositions.

Many people with ancestry in Europe, West Asia, South Asia, the Sahel belt in West Africa, East Africa and a few other parts of Central Africa maintain lactase production into adulthood. In many of these areas, milk from mammals such as cattle, goats, and sheep is used as a large source of food. Hence, it was in these regions that genes for lifelong lactase production first evolved. The genes of adult lactose tolerance have evolved independently in various ethnic groups.[13] By descent, more than 70% of western Europeans can digest lactose as adults, compared with less than 30% of people from areas of Africa, eastern and south-eastern Asia and Oceania.[14] In people who are lactose intolerant, lactose is not broken down and provides food for gas-producing gut flora, which can lead to diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Biological properties

The sweetness of lactose is 0.2 to 0.4, relative to 1.0 for sucrose.[15] For comparison, the sweetness of glucose is 0.6 to 0.7, of fructose is 1.3, of galactose is 0.5 to 0.7, of maltose is 0.4 to 0.5, of sorbose is 0.4, and of xylose is 0.6 to 0.7.[15]

When lactose is completely digested in the small intestine, its caloric value is 4 kcal/g, or the same as that of other carbohydrates.[15] However, lactose is not always fully digested in the small intestine.[15] Depending on ingested dose, combination with meals (either solid or liquid), and lactase activity in the intestines, the caloric value of lactose ranges from 2 to 4 kcal/g.[15] Undigested lactose acts as dietary fiber.[15] It also has positive effects on absorption of minerals, such as calcium and magnesium.[15]

The glycemic index of lactose is 46 to 65.[15][16] For comparison, the glycemic index of glucose is 100 to 138, of sucrose is 68 to 92, of maltose is 105, and of fructose is 19 to 27.[15][16]

Lactose has relatively low cariogenicity among sugars.[17][15] This is because it is not a substrate for dental plaque formation and it is not rapidly fermented by oral bacteria.[17][15] The buffering capacity of milk also reduces the cariogenicity of lactose.[15]

Applications

Its mild flavor and easy handling properties have led to its use as a carrier and stabiliser of aromas and pharmaceutical products.[5] Lactose is not added directly to many foods, because its solubility is less than that of other sugars commonly used in food. Infant formula is a notable exception, where the addition of lactose is necessary to match the composition of human milk.

Lactose is not fermented by most yeast during brewing, which may be used to advantage.[9] For example, lactose may be used to sweeten stout beer; the resulting beer is usually called a milk stout or a cream stout.

Yeast belonging to the genus Kluyveromyces have a unique industrial application, as they are capable of fermenting lactose for ethanol production. Surplus lactose from the whey by-product of dairy operations is a potential source of alternative energy.[18]

Another significant lactose use is in the pharmaceutical industry. Lactose is added to tablet and capsule drug products as an ingredient because of its physical and functional properties.[5] For similar reasons, it can be used to dilute illicit drugs such as cocaine or heroin.[19]

History

The first crude isolation of lactose, by Italian physician Fabrizio Bartoletti (1576–1630), was published in 1633.[20] In 1700, the Venetian pharmacist Lodovico Testi (1640–1707) published a booklet of testimonials to the power of milk sugar (saccharum lactis) to relieve, among other ailments, the symptoms of arthritis.[21] In 1715, Testi's procedure for making milk sugar was published by Antonio Vallisneri.[22] Lactose was identified as a sugar in 1780 by Carl Wilhelm Scheele.[23][9]

In 1812, Heinrich Vogel (1778–1867) recognized that glucose was a product of hydrolyzing lactose.[24] In 1856, Louis Pasteur crystallized the other component of lactose, galactose.[25] By 1894, Emil Fischer had established the configurations of the component sugars.[26]

Lactose was named by the French chemist Jean Baptiste André Dumas (1800–1884) in 1843.[27] In 1856, Pasteur named galactose "lactose".[28] In 1860, Marcellin Berthelot renamed it "galactose", and transferred the name "lactose" to what is now called lactose.[29] It has a formula of C12H22O11 and the hydrate formula C12H22O11·H2O, making it an isomer of sucrose.

See also

References

- 1 2 Peter M. Collins (2006). Dictionary of Carbohydrates (2nd ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. p. 677. ISBN 978-0-8493-3829-8.

- ↑ "D-Lactose".

- ↑ The solubility of lactose in water is 189.049 g at 25 °C, 251.484 g at 40 °C and 372.149 g at 60 °C per kg solution. Its solubility in ethanol is 0.111 g at 40 °C and 0.270 g at 60 °C per kg solution.Machado, José J. B.; Coutinho, João A.; Macedo, Eugénia A. (2001), "Solid–liquid equilibrium of α-lactose in ethanol/water" (PDF), Fluid Phase Equilibria, 173 (1): 121–34, doi:10.1016/S0378-3812(00)00388-5. ds

- ↑ Sigma Aldrich

- 1 2 3 Gerrit M. Westhoff; Ben F.M. Kuster; Michiel C. Heslinga; Hendrik Pluim; Marinus Verhage (2014). "Lactose and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_107.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ↑ Ruppersberg, Klaus; Blankenburg, Janet (2018). "150 Years Alfred Wöhlk". ChemViews. doi:10.1002/chemv.201800002.

- ↑ Fearon, W. R. (1942). "The detection of lactose and maltose by means of methylamine". The Analyst. 67 (793): 130. doi:10.1039/an9426700130. ISSN 0003-2654.

- ↑ Ruppersberg, Klaus; Herzog, Stefanie; Kussler, Manfred W.; Parchmann, Ilka (2019-10-17). "How to visualize the different lactose content of dairy products by Fearon's test and Woehlk test in classroom experiments and a new approach to the mechanisms and formulae of the mysterious red dyes". Chemistry Teacher International. 2 (2). doi:10.1515/cti-2019-0008. ISSN 2569-3263. S2CID 208714341.

- 1 2 3 Linko, P (1982), "Lactose and Lactitol", in Birch, G.G.; Parker, K.J (eds.), Natural Sweeteners, London & New Jersey: Applied Science Publishers, pp. 109–132, ISBN 978-0-85334-997-6

- ↑ Ranken, M. D.; Kill, R. C. (1997), Food industries manual, Springer, p. 125, ISBN 978-0-7514-0404-3

- ↑ Wong, S. Y.; Hartel, R. W. (2014), "Crystallization in lactose refining-a review", Journal of Food Science, 79 (3): R257–72, doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12349, PMID 24517206, DOI is open access

- ↑ Pavia, Donald L.; Lampman, Gary M.; Kriz, George S. (1990), Introduction to Organic Laboratory Techniques: A Microscale Approach, Saunders, ISBN 0-03-014813-8

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2006-12-10), "Study Detects Recent Instance of Human Evolution", New York Times.

- ↑ Ridley, Matt (1999), Genome, HarperCollins, p. 193, ISBN 978-0-06-089408-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Schaafsma, Gertjan (2008). "Lactose and lactose derivatives as bioactive ingredients in human nutrition" (PDF). International Dairy Journal. 18 (5): 458–465. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2007.11.013. ISSN 0958-6946. S2CID 10346203. Archived from the original (PDF) on Mar 2, 2019.

- 1 2 Björck, Inger; Liljeberg, Helena; Östman, Elin (2000). "Low glycaemic-index foods". British Journal of Nutrition. 83 (S1): S149–S155. doi:10.1017/S0007114500001094. ISSN 0007-1145. PMID 10889806. S2CID 14574754.

- 1 2 Gregory D. Miller; Judith K. Jarvis; Lois D. McBean (15 December 2006). Handbook of Dairy Foods and Nutrition. CRC Press. pp. 248–. ISBN 978-1-4200-0431-1.

- ↑ Ling, Charles (2008), Whey to Ethanol: A Biofuel Role for Dairy Cooperatives? (PDF), United States Department of Agriculture Rural Development.

- ↑ Rinaldi, R.; Negro, F.; Minutillo, A. (2020-02-20). "The health threat of new synthetic opioids as adulterants of classic drugs of abuse" (PDF). La Clinica Terapeutica. 171 (2): 107–109. doi:10.7417/CT.2020.2198. ISSN 1972-6007. PMID 32141480.

- ↑ Fabrizio Bartoletti, Methodus in dyspnoeam … [Procedure for asthma … ], (Bologna ("Bononia"), (Italy): Nicolò Tebaldini for the heirs of Evangelista Dozza, 1633), p. 400. From page 400: "Manna seri hæc. Destilla leni balnei calore serum lactis, donec in fundo vasis butyracea fœx subsideat, cui hærebit salina quædam substantia subalbida. Hanc curiose segrega, est enim sal seri essentiale; seu nitrum, cujus causa nitrosum dicitut serum, huicque tota abstergedi vis inest. Solve in aqua propria, & coagula. Opus repete, donec seri cremorem habeas sapore omnino mannam referentem." (This is the manna of whey. [Note: "Manna" was the dried, sweet sap of the tree Fraxinus ornus.] Gently distill whey via a heat bath until the buttery scum settles to the bottom of the vessel, to which substance some whitish salt [i.e., precipitate] attaches. This curious [substance once] separated, is truly the essential salt of whey; or, on account of which nitre, is called "nitre of whey", and all [life] force is in this that will be expelled. [Note: "Nitre" was an alchemical concept. It was the power of life, which gave life to otherwise inanimate matter. See the philosophy of Sendivogius.] Dissolve it in [its] own water and coagulate. Repeat the operation until you have cream of whey, recalling, by [its] taste, only manna.)

In 1688, the German physician Michael Ettmüller (1644–1683) reprinted Bartoletti's preparation. See: Ettmüller, Michael, Opera Omnia … (Frankfurt am Main ("Francofurtum ad Moenum"), [Germany]: Johann David Zunner, 1688), book 2, page 163. Archived 2018-11-09 at the Wayback Machine From page 163: "Undd Bertholetus praeparat ex sero lactis remedium, quod vocat mannam S. [alchemical symbol for salt, salem] seri lactis vid. in Encyclopaed. p. 400. Praeparatio est haec: … " (Whence Bartoletti prepared from milk whey a medicine, which he called manna or salt of milk whey; see in [his] Encyclopedia [note: this is a mistake; the preparation appeared in Bartoletti's Methodus in dyspnoeam … ], p. 400. This is the preparation: … ) - ↑ Lodovico Testi, De novo Saccharo Lactis [On the new milk sugar] (Venice, (Italy): Hertz, 1700).

- ↑ Ludovico Testi (1715) "Saccharum lactis" (Milk sugar), Academiae Caesareo-Leopoldinae naturae curiosorum ephemerides, … , 3 : 69–79. The procedure was also published in Giornale de' letterati d'Italia in 1715.

- ↑ See:

- Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1780) "Om Mjölk och dess syra" (About milk and its acid), Kongliga Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar (New Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Science), 1 : 116–124. From page 116: "Det år bekant, at Ko-mjölk innehåller Smör, Ost, Mjölk-såcker, … " (It is known, that cow's milk contains butter, cheese, milk-sugar, … )

- Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1780) "Om Mjölk-Såcker-Syra" (On milk-sugar acid), Kongliga Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar (New Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Science), 1 : 269–275. From pages 269–270: "Mjölk-Såcker år et sal essentiale, som uti Mjölken finnes uplöst, och som, för dess sötaktiga smak skull, fått namn af såcker." (Milk sugar is an essential salt, which is found dissolved in milk, and which, on account of its sweet taste, has the name of "sugar".)

- ↑ See:

- Vogel (1812) "Sur le sucre liquide d'amidon, et sur la transmutation des matières douces en sucre fermentescible" (On the liquid sugar of starch, and on the transformation of sweet materials into fermentable sugars), Annales de chemie et de physique, series 1, 82 : 148–164; see especially pages 156–158.

- H. A. Vogel (1812) "Ueber die Verwandlung der Stärke und andrer Körper in Zucker" (On the conversion of starches and other substances into sugar), Annalen der Physik, new series, 42 : 123–134; see especially pages 129–131.

- ↑ Pasteur (1856) "Note sur le sucre de lait" (Note on milk sugar), Comptes rendus, 42 : 347–351.

- ↑ Fischer determined the configuration of glucose in:

- Emil Fischer (1891) "Ueber die Configuration des Traubenzuckers und seiner Isomeren" (On the configuration of grape sugar and its isomers), Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 24 : 1836–1845.

- Emil Fischer (1891) "Ueber die Configuration des Traubenzuckers und seiner Isomeren. II" (On the configuration of grape sugar and its isomers), Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft, 24 : 2683–2687.

- Emil Fischer and Robert S. Morrell (1894) "Ueber die Configuration der Rhamnose und Galactose" (On the configuration of rhamnose and galactose), Berichte der Deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin, 27 : 382–394. The configuration of galactose appears on page 385.

- ↑ Dumas, Traité de Chimie, Appliquée aux Arts, volume 6 (Paris, France: Bechet Jeune, 1843), p. 293.

- ↑ Pasteur (1856) "Note sur le sucre de lait" (Note on milk sugar), Comptes rendus, 42 : 347–351. From page 348: "Je propose de le nommer lactose." (I propose to name it lactose.)

- ↑ Marcellin Berthelot, Chimie organique fondée sur la synthèse [Organic chemistry based on synthesis] (Paris, France: Mallet-Bachelier, 1860), vol. 2, pp. 248–249 and pp. 268–270.

External links

Media related to Lactose at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lactose at Wikimedia Commons