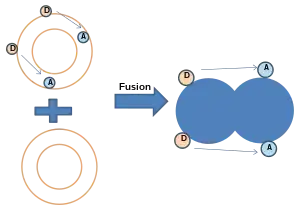

In membrane biology, fusion is the process by which two initially distinct lipid bilayers merge their hydrophobic cores, resulting in one interconnected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, an aqueous bridge is formed and the internal contents of the two structures can mix. Alternatively, if only one leaflet from each bilayer is involved in the fusion process, the bilayers are said to be hemifused. In hemifusion, the lipid constituents of the outer leaflet of the two bilayers can mix, but the inner leaflets remain distinct. The aqueous contents enclosed by each bilayer also remain separated.

Fusion is involved in many cellular processes, particularly in eukaryotes since the eukaryotic cell is extensively sub-divided by lipid bilayer membranes. Exocytosis, fertilization of an egg by sperm and transport of waste products to the lysosome are a few of the many eukaryotic processes that rely on some form of fusion. Fusion is also an important mechanism for transport of lipids from their site of synthesis to the membrane where they are needed. Even the entry of pathogens can be governed by fusion, as many bilayer-coated viruses have dedicated fusion proteins to gain entry into the host cell.

Lipid mechanism

There are four fundamental steps in the fusion process, although each of these steps actually represents a complex sequence of events.[1] First, the involved membranes must aggregate, approaching each other to within several nanometers. Second, the two bilayers must come into very close contact (within a few angstroms). To achieve this close contact, the two surfaces must become at least partially dehydrated, as the bound surface water normally present causes bilayers to strongly repel at this distance. Third, a destabilization must develop at one point between the two bilayers, inducing a highly localized rearrangement of the two bilayers. Finally, as this point defect grows, the components of the two bilayers mix and diffuse away from the site of contact. Depending on whether hemifusion or full fusion occurs, the internal contents of the membranes may mix at this point as well.

The exact mechanisms behind this complex sequence of events are still a matter of debate. To simplify the system and allow more definitive study, many experiments have been performed in vitro with synthetic lipid vesicles. These studies have shown that divalent cations play a critical role in the fusion process by binding to negatively charged lipids such as phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylglycerol and cardiolipin.[2] One role on these ions in the fusion process is to shield the negative charge on the surface of the bilayer, diminishing electrostatic repulsion and allowing the membranes to approach each other. This is clearly not the only role, however, since there is an extensively documented difference in the ability of Mg2+ versus Ca2+ to induce fusion. Although Mg2+ will induce extensive aggregation it will not induce fusion, while Ca2+ induces both.[3] It has been proposed that this discrepancy is due to a difference in extent of dehydration. Under this theory, calcium ions bind more strongly to charged lipids, but less strongly to water. The resulting displacement of calcium for water destabilizes the lipid-water interface and promotes intimate interbilayer contact.[4] A recently proposed alternative hypothesis is that the binding of calcium induces a destabilizing lateral tension.[5] Whatever the mechanism of calcium-induced fusion, the initial interaction is clearly electrostatic, since zwitterionic lipids are not susceptible to this effect.[6][7]

In the fusion process, the lipid head group is not only involved in charge density, but can affect dehydration and defect nucleation. These effects are independent of the effects of ions. The presence of the uncharged headgroup phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) increases fusion when incorporated into a phosphatidylcholine bilayer. This phenomenon has been explained by some as a dehydration effect similar to the influence of calcium.[8] The PE headgroup binds water less tightly than PC and therefore may allow close apposition more easily. An alternate explanation is that the physical rather than chemical nature of PE may help induce fusion. According to the stalk hypothesis of fusion, a highly curved bridge must form between the two bilayers for fusion to occur.[9] Since PE has a small headgroup and readily forms inverted micelle phases it should, according to the stalk model, promote the formation of these stalks.[10] Further evidence cited in favor of this theory is the fact that certain lipid mixtures have been shown to only support fusion when raised above the transition temperature of these inverted phases.[11][12] This topic also remains controversial, and even if there is a curved structure present in the fusion process, there is debate in the literature over whether it is a cubic, hexagonal or more exotic extended phase.[13]

Fusion proteins

The situation is further complicated when considering fusion in vivo since biological fusion is almost always regulated by the action of membrane-associated proteins. The first of these proteins to be studied were the viral fusion proteins, which allow an enveloped virus to insert its genetic material into the host cell (enveloped viruses are those surrounded by a lipid bilayer; some others have only a protein coat). Broadly, there are two classes of viral fusion proteins: acidic and pH-independent.[1] pH independent fusion proteins can function under neutral conditions and fuse with the plasma membrane, allowing viral entry into the cell. Viruses utilizing this scheme included HIV, measles and herpes. Acidic fusion proteins such as those found on influenza are only activated when in the low pH of acidic endosomes and must first be endocytosed to gain entry into the cell.

Eukaryotic cells use entirely different classes of fusion proteins, the best studied of which are the SNAREs. SNARE proteins are used to direct all vesicular intracellular trafficking. Despite years of study, much is still unknown about the function of this protein class. In fact, there is still an active debate regarding whether SNAREs are linked to early docking or participate later in the fusion process by facilitating hemifusion.[15] Even once the role of SNAREs or other specific proteins is illuminated, a unified understanding of fusion proteins is unlikely as there is an enormous diversity of structure and function within these classes, and very few themes are conserved.[16]

Fusion in laboratory practice

In studies of molecular and cellular biology it is often desirable to artificially induce fusion. Although this can be accomplished with the addition of calcium as discussed earlier, this procedure is often not feasible because calcium regulates many other biochemical processes and its addition would be a strong confound. Also, as mentioned, calcium induces massive aggregation as well as fusion. The addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) causes fusion without significant aggregation or biochemical disruption. This procedure is now used extensively, for example by fusing B-cells with myeloma cells.[17] The resulting “hybridoma” from this combination expresses a desired antibody as determined by the B-cell involved, but is immortalized due to the myeloma component. The mechanism of PEG fusion has not been definitively identified, but some researchers believe that the PEG, by binding a large number of water molecules, effectively decreases the chemical activity of the water and thus dehydrates the lipid headgroups.[18] Fusion can also be artificially induced through electroporation in a process known as electrofusion. It is believed that this phenomenon results from the energetically active edges formed during electroporation, which can act as the local defect point to nucleate stalk growth between two bilayers.[19]

Alternatively, SNARE-inspired model systems can be used to induce membrane fusion of lipid vesicles. In those systems membrane anchored complementary DNA,[20][21][22] PNA,[23] peptides,[24] or other molecules[25] "zip" together and pull the membranes into proximity. Such systems could have practical applications in the future, for example in drug delivery.[26] The probably best investigated system[27] consists of coiled-coil forming peptides of complementary charge (one is typically carrying an excess of positively charged lysins and is thus termed peptide K, and one negatively charged glutamic acids called peptide E).[28] Interestingly, it was discovered that not only the coiled-coil formation between the two peptides is necessary for membrane fusion to occur, but also that the peptide K interacts with the membrane surface and cause local defects.[29]

Assays to measure membrane fusion

There are two levels of fusion: mixing of membrane lipids and mixing of contents. Assays of membrane fusion report either the mixing of membrane lipids or the mixing of the aqueous contents of the fused entities.

Assays for measuring lipid mixing

Assays evaluating lipid mixing make use of concentration dependent effects such as nonradiative energy transfer, fluorescence quenching and pyrene excimer formation.

- NBD-Rhodamine Energy Transfer:[30] In this method, membrane labeled with both NBD (donor) and Rhodamine (acceptor) combine with unlabeled membrane. When NBD and Rhodamine are within a certain distance, the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) happens. After fusion, resonance energy transfer (FRET) decreases when the average distance between probes increases, while NBD fluorescence increases.

- Pyrene Excimer Formation: Pyrene monomer and excimer emission wavelengths are different. The emission wavelength of monomer is around 400 nm and that of excimer is around 470 nm. In this method, membrane labeled with Pyrene combines with unlabeled membrane. Pyrene self associates in membrane and then excited pyrene excites other pyrene. Before fusion, the majority of the emission is excimer emission. After fusion, the distance between probes increases and the ratio of excimer emission decreases.

- Octadecyl Rhodamine B Self-Quenching:[31] This assay is based on self-quenching of octadecyl rhodamine B. Octadecyl rhodamine B self-quenching occurs when the probe is incorporated into membrane lipids at concentrations of 1–10 mole percent[32] because Rhodamine dimers quench fluorescence. In this method, membrane labeled Rhodamine combines with unlabeled membrane. Fusion with unlabeled membranes resulting in dilution of the probe, which is accompanied by increasing fluorescence.[33][34] The major problem of this assay is spontaneous transfer.

Assays for measuring content mixing

Mixing of aqueous contents from vesicles as a result of lysis, fusion or physiological permeability can be detected fluorometrically using low molecular weight soluble tracers.

- Fluorescence quenching assays with ANTS/DPX:[35][36] ANTS is a polyanionic fluorophore, while DPX is a cationic quencher. The assay is based on the collisional quenching of them. Separate vesicle populations are loaded with ANTS or DPX, respectively. When content mixing happens, ANTS and DPX collide and fluorescence of ANTS monitored at 530 nm, with excitation at 360 nm is quenched. This method is performed at acidic pH and high concentration.

- Fluorescence enhancement assays with Tb3+/DPA:[37][38] This method is based on the fact that chelate of Tb3+/DPA is 10,000 times more fluorescent than Tb3+ alone. In the Tb3+/DPA assay, separate vesicle populations are loaded with TbCl3 or DPA. The formation of Tb3+/DPA chelate can be used to indicate vesicle fusion. This method is good for protein free membranes.

- Single molecule DNA assay.[39] A DNA hairpin composed of 5 base pair stem and poly-thymidine loop that is labeled with a donor (Cy3) and an acceptor (Cy5) at the ends of the stem was encapsulated in the v-SNARE vesicle. We separately encapsulated multiple unlabeled poly-adenosine DNA strands in the t-SNARE vesicle. If the two vesicles, both ~100 nm in diameter, dock and a large enough fusion pore forms between them, the two DNA molecules should hybridize, opening up the stem region of the hairpin and switching the Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) efficiency (E) between Cy3 and Cy5 from a high to a low value.

See also

References

- 1 2 Yeagle, P. L. (1993). The Membranes of Cells (2nd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 9780127690414.

- ↑ Papahadjopoulos, Demetrios; Nir, Shlomo; Düzgünes, Nejat (1990). "Molecular mechanisms of calcium-induced membrane fusion". Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 22 (2): 157–79. doi:10.1007/BF00762944. PMID 2139437. S2CID 1465571.

- ↑ Leventis, Rania; Gagne, Jeannine; Fuller, Nola; Rand, R.; Silvius, J. (1986). "Divalent Cation Induced Fusion and Lipid Lateral Segregation in Phosphatidylcholine-Phosphatidic Acid Vesicles". Biochemistry. 25 (22): 6978–87. doi:10.1021/bi00370a600. PMID 3801406.

- ↑ Wilschut, Jan; Duezguenes, Nejat; Papahadjopoulos, Demetrios (1981). "Calcium/magnesium specificity in membrane fusion: Kinetics of aggregation and fusion of phosphatidylserine vesicles and the role of bilayer curvature". Biochemistry. 20 (11): 3126–33. doi:10.1021/bi00514a022. PMID 7248275.

- ↑ Chanturiya, A; Scaria, P; Woodle, MC (2000). "The Role of Membrane Lateral Tension in Calcium-Induced Membrane Fusion". The Journal of Membrane Biology. 176 (1): 67–75. doi:10.1007/s00232001076. PMID 10882429. S2CID 2209769.

- ↑ Pannuzzo, Martina; Jong, De; Djurre, H.; Raudino, Antonio; Marrink Siewert, J. (2014). "Simulation of polyethylene glycol and calcium-mediated membrane fusion" (PDF). J. Chem. Phys. 140 (12): 124905. Bibcode:2014JChPh.140l4905P. doi:10.1063/1.4869176. hdl:11370/78e66c44-d236-4336-9b4a-151d52ffa961. PMID 24697479. S2CID 7548382.

- ↑ Papahadjopoulos, D.; Poste, G.; Schaeffer, B.E.; Vail, W.J. (1974). "Membrane fusion and molecular segregation in phospholipid vesicles". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 352 (1): 10–28. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(74)90175-8. PMID 4859411.

- ↑ Düzgünes, Nejat; Wilschut, Jan; Fraley, Robert; Papahadjopoulos, Demetrios (1981). "Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion. Role of head-group composition in calcium- and magnesium-induced fusion of mixed phospholipid vesicles". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 642 (1): 182–95. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(81)90148-6. PMID 7225377.

- ↑ Markin, VS; Kozlov, MM; Borovjagin, VL (1984). "On the theory of membrane fusion. The stalk mechanism" (PDF). General Physiology and Biophysics. 3 (5): 361–77. PMID 6510702.

- ↑ Chernomordik, Leonid V.; Kozlov, Michael M. (2003). "Protein-lipid interplay in fusion and fission of biological membranes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 72: 175–207. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161504. PMID 14527322.

- ↑ Nir, S.; Bentz, J.; Wilschut, J.; Duzgunes, N. (1983). "Aggregation and fusion of phospholipid vesicles". Progress in Surface Science. 13 (1): 1–124. Bibcode:1983PrSS...13....1N. doi:10.1016/0079-6816(83)90010-2.

- ↑ Ellens, Harma; Bentz, Joe; Szoka, Francis C. (1986). "Fusion of phosphatidylethanolamine-containing liposomes and mechanism of L.alpha.-HII phase transition". Biochemistry. 25 (14): 4141–7. doi:10.1021/bi00362a023. PMID 3741846.

- ↑ Holopainen, Juha M.; Lehtonen, Jukka Y.A.; Kinnunen, Paavo K.J. (1999). "Evidence for the Extended Phospholipid Conformation in Membrane Fusion and Hemifusion". Biophysical Journal. 76 (4): 2111–20. Bibcode:1999BpJ....76.2111H. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77367-4. PMC 1300184. PMID 10096906.

- ↑ Georgiev, Danko D.; Glazebrook, James F. (2007). "Subneuronal processing of information by solitary waves and stochastic processes". In Lyshevski, Sergey Edward (ed.). Nano and Molecular Electronics Handbook (PDF). Nano and Microengineering Series. CRC Press. pp. 17–1–17–41. doi:10.1201/9781315221670. ISBN 978-0-8493-8528-5.

- ↑ Chen, Yu A.; Scheller, Richard H. (2001). "SNARE-mediated membrane fusion". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2 (2): 98–106. doi:10.1038/35052017. PMID 11252968. S2CID 205012830.

- ↑ White, J M (1990). "Viral and Cellular Membrane Fusion Proteins". Annual Review of Physiology. 52: 675–97. doi:10.1146/annurev.ph.52.030190.003331. PMID 2184772.

- ↑ Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. (1975). "Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity". Nature. 256 (5517): 495–7. Bibcode:1975Natur.256..495K. doi:10.1038/256495a0. PMID 1172191. S2CID 4161444.

- ↑ Lentz, Barry R. (1994). "Polymer-induced membrane fusion: Potential mechanism and relation to cell fusion events". Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 73 (1–2): 91–106. doi:10.1016/0009-3084(94)90176-7. PMID 8001186.

- ↑ Jordan, C. A.; Neumann, E.; Sowers, A. E., eds. (1989). Electroporation and Electrofusion in Cell Biology. Springer. ISBN 978-0-306-43043-5.

- ↑ Malle, M.G.; Löffler, P.M.G; Bohr, S.SR.; et al. (4 April 2022). "Single-particle combinatorial multiplexed liposome fusion mediated by DNA". Nat. Chem. 14 (5): 558–565. Bibcode:2022NatCh..14..558M. doi:10.1038/s41557-022-00912-5. PMID 35379901. S2CID 247942781.

- ↑ Löffler, Philipp M. G.; Ries, Oliver; Rabe, Alexander; Okholm, Anders H.; Thomsen, Rasmus P.; Kjems, Jørgen; Vogel, Stefan (2017). "A DNA-Programmed Liposome Fusion Cascade". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 56 (43): 13228–13231. doi:10.1002/anie.201703243. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 28598002. S2CID 205401773.

- ↑ Stengel, Gudrun; Zahn, Raphael; Höök, Fredrik (2007-08-01). "DNA-Induced Programmable Fusion of Phospholipid Vesicles". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (31): 9584–9585. doi:10.1021/ja073200k. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 17629277.

- ↑ Lygina, Antonina S.; Meyenberg, Karsten; Jahn, Reinhard; Diederichsen, Ulf (2011). "Transmembrane Domain Peptide/Peptide Nucleic Acid Hybrid as a Model of a SNARE Protein in Vesicle Fusion". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (37): 8597–8601. doi:10.1002/anie.201101951. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-000F-41FF-2. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 21786370.

- ↑ Litowski, J. R.; Hodges, R. S. (2002-10-04). "Designing Heterodimeric Two-stranded α-Helical Coiled-coils: EFFECTS OF HYDROPHOBICITY AND α-HELICAL PROPENSITY ON PROTEIN FOLDING, STABILITY, AND SPECIFICITY". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (40): 37272–37279. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204257200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 12138097. S2CID 84379119.

- ↑ Kumar, Pawan; Guha, Samit; Diederichsen, Ulf (2015). "SNARE protein analog-mediated membrane fusion". Journal of Peptide Science. 21 (8): 621–629. doi:10.1002/psc.2773. ISSN 1099-1387. PMID 25858776. S2CID 23718905.

- ↑ Yang, Jian; Bahreman, Azadeh; Daudey, Geert; Bussmann, Jeroen; Olsthoorn, René C. L.; Kros, Alexander (2016-09-28). "Drug Delivery via Cell Membrane Fusion Using Lipopeptide Modified Liposomes". ACS Central Science. 2 (9): 621–630. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.6b00172. ISSN 2374-7943. PMC 5043431. PMID 27725960.

- ↑ Robson Marsden, Hana; Elbers, Nina A.; Bomans, Paul H. H.; Sommerdijk, Nico A. J. M.; Kros, Alexander (2009). "A Reduced SNARE Model for Membrane Fusion". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 48 (13): 2330–2333. doi:10.1002/anie.200804493. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 19222065.

- ↑ Lindhout, Darrin A.; Litowski, Jennifer R.; Mercier, Pascal; Hodges, Robert S.; Sykes, Brian D. (2004). "NMR solution structure of a highly stable de novo heterodimeric coiled-coil". Biopolymers. 75 (5): 367–375. doi:10.1002/bip.20150. ISSN 1097-0282. PMID 15457434. S2CID 28856028.

- ↑ Rabe, Martin; Aisenbrey, Christopher; Pluhackova, Kristyna; De Wert, Vincent; Boyle, Aimee L.; Bruggeman, Didjay F.; Kirsch, Sonja A.; Böckmann, Rainer A.; Kros, Alexander; Raap, Jan; Bechinger, Burkhard (2016-11-15). "A Coiled-Coil Peptide Shaping Lipid Bilayers upon Fusion". Biophysical Journal. 111 (10): 2162–2175. Bibcode:2016BpJ...111.2162R. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2016.10.010. ISSN 0006-3495. PMC 5113151. PMID 27851940.

- ↑ Struck, Douglas K.; Hoekstra, Dick; Pagano, Richard E. (1981). "Use of resonance energy transfer to monitor membrane fusion". Biochemistry. 20 (14): 4093–9. doi:10.1021/bi00517a023. PMID 7284312.

- ↑ Hoekstra, Dick; De Boer, Tiny; Klappe, Karin; Wilschut, Jan (1984). "Fluorescence method for measuring the kinetics of fusion between biological membranes". Biochemistry. 23 (24): 5675–81. doi:10.1021/bi00319a002. PMID 6098295.

- ↑ MacDonald, Ruby I (1990). "Characteristics of self-quenching of the fluorescence of lipid-conjugated rhodamine in membranes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (23): 13533–9. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)77380-8. PMID 2380172.

- ↑ Rubin, R.J.; Chen, Y.D. (1990). "Diffusion and redistribution of lipid-like molecules between membranes in virus-cell and cell-cell fusion systems". Biophysical Journal. 58 (5): 1157–67. Bibcode:1990BpJ....58.1157R. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82457-7. PMC 1281061. PMID 2291940.

- ↑ Chen, Y.D.; Rubin, R.J.; Szabo, A. (1993). "Fluorescence dequenching kinetics of single cell-cell fusion complexes". Biophysical Journal. 65 (1): 325–33. Bibcode:1993BpJ....65..325C. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81076-2. PMC 1225727. PMID 8369440.

- ↑ Smolarsky, Moshe; Teitelbaum, Dvora; Sela, Michael; Gitler, Carlos (1977). "A simple fluorescent method to determine complement-mediated liposome immune lysis". Journal of Immunological Methods. 15 (3): 255–65. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(77)90063-1. PMID 323363.

- ↑ Ellens, H; Bentz, J; Szoka, FC (1985). "H+- and Ca2+-induced fusion and destabilization of liposomes". Biochemistry. 24 (13): 3099–106. doi:10.1021/bi00334a005. PMID 4027232.

- ↑ Wilschut, Jan; Papahadjopoulos, Demetrios (1979). "Ca2+-induced fusion of phospholipid vesicles monitored by mixing of aqueous contents". Nature. 281 (5733): 690–2. Bibcode:1979Natur.281..690W. doi:10.1038/281690a0. PMID 551288. S2CID 4353081.

- ↑ Wilschut, Jan; Duzgunes, Nejat; Fraley, Robert; Papahadjopoulos, Demetrios (1980). "Studies on the mechanism of membrane fusion: Kinetics of calcium ion induced fusion of phosphatidylserine vesicles followed by a new assay for mixing of aqueous vesicle contents". Biochemistry. 19 (26): 6011–21. doi:10.1021/bi00567a011. PMID 7470445.

- ↑ Diao, Jiajie; Su, Zengliu; Ishitsuka, Yuji; Lu, Bin; Lee, Kyung Suk; Lai, Ying; Shin, Yeon-Kyun; Ha, Taekjip (2010). "A single-vesicle content mixing assay for SNARE-mediated membrane fusion". Nature Communications. 1 (5): 1–6. Bibcode:2010NatCo...1E..54D. doi:10.1038/ncomms1054. PMC 3518844. PMID 20975723.