A soap bubble (commonly referred to as simply a bubble) is an extremely thin film of soap or detergent and water enclosing air that forms a hollow sphere with an iridescent surface. Soap bubbles usually last for only a few seconds before bursting, either on their own or on contact with another object. They are often used for children's enjoyment, but they are also used in artistic performances. Assembling many bubbles results in foam.

When light shines onto a bubble it appears to change colour. Unlike those seen in a rainbow, which arise from differential refraction, the colours seen in a soap bubble arise from light wave interference, reflecting off the front and back surfaces of the thin soap film. Depending on the thickness of the film, different colours interfere constructively and destructively.

Mathematics

Soap bubbles are physical examples of the complex mathematical problem of minimal surface. They will assume the shape of least surface area possible containing a given volume. A true minimal surface is more properly illustrated by a soap film, which has equal pressure on both sides, becoming a surface with zero mean curvature. A soap bubble is a closed soap film: due to the difference in outside and inside pressure, it is a surface of constant mean curvature.

While it has been known since 1884 that a spherical soap bubble is the least-area way of enclosing a given volume of air (a theorem of H. A. Schwarz), it was not until 2000 that it was proven that two merged soap bubbles provide the optimum way of enclosing two given volumes of air of different size with the least surface area. This has been dubbed the double bubble conjecture.[1]

Because of these qualities, soap bubble films have been used in practical problem solving applications. Structural engineer Frei Otto used soap bubble films to determine the geometry of a sheet of least surface area that spreads between several points, and translated this geometry into revolutionary tensile roof structures.[2] A famous example is his West German Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal.

Soap bubbles as unconventional computing

The structures that soap films make can not just be enclosed as spheres, but virtually any shape, for example in wire frames. Therefore, many different minimal surfaces can be designed. It is actually sometimes easier to physically make them than to compute them by mathematical modelling. This is why the soap films can be considered as analog computers which can outperform conventional computers, depending on the complexity of the system.[3][4][5]

Physics

Merging

When two bubbles merge, they adopt a shape which makes the sum of their surface areas as small as possible, compatible with the volume of air each bubble encloses. If the bubbles are of equal size, their common wall is flat. If they are not the same size, their common wall bulges into the larger bubble, since the smaller one has a higher internal pressure than the larger one, as predicted by the Young–Laplace equation.

At a point where three or more bubbles meet, they sort themselves out so that only three bubble walls meet along a line. Since the surface tension is the same in each of the three surfaces, the three angles between them must be equal to 120°. Only four bubble walls can meet at a point, with the lines where triplets of bubble walls meet separated by cos−1(−1/3) ≈ 109.47°. All these rules, known as Plateau's laws, determine how a foam is built from bubbles.

Stability

The longevity of a soap bubble is limited by the ease of rupture of the very thin layer of water which constitutes its surface, namely a micrometer-thick soap film. It is thus sensitive to :

- Drainage within the soap film: water falls down due to gravity. This can be slowed by increasing the water viscosity, for instance by adding glycerol. Still, there is an ultimate height limit, which is the capillary length, very high for soap bubbles: around 13 feet (4 meters). In principle, there is no limit in the length it can reach.

- Evaporation: This can be slowed by blowing bubbles in a wet atmosphere, or by adding some sugar to the water.

- Dirt and fat: When the bubble touches an object, it usually ruptures the soap film. This can be prevented by wetting these surfaces with water (preferably containing some soap).

After experiments, researchers found that a solution containing:

- 85.9 % water

- 10 % glycerol

- 4 % washing-up liquid

- 0.1 % guar gum

gave the longest lasting results as it minimised the Marangoni Effect.[6]

Wetting

When a soap bubble is in contact with a solid or a liquid surface wetting is observed. On a solid surface, the contact angle of the bubble depends on the surface energy of the solid.,[7][8] A soap bubble has a larger contact angle on a solid surface displaying ultrahydrophobicity than on a hydrophilic surface – see Wetting. On a liquid surface, the contact angle of the soap bubble depends on its size - smaller bubbles have lower contact angles.[9][10]

A soap bubble wetting an ultrahydrophobic surface

A soap bubble wetting an ultrahydrophobic surface A soap bubble wetting a liquid surface

A soap bubble wetting a liquid surface

Floatation

The gas inside a bubble is less dense than air because it is mostly water vapor. Water vapor is a gas that is formed when water molecules evaporate. When water molecules evaporate, they escape from the liquid state and enter the gas state. In the gas state, water molecules are further apart than they are in the liquid state. This is because water molecules are attracted to each other. When they evaporate, they break away from these attractions and move further apart.

The further apart water molecules are, the less dense they are. This is why water vapor is less dense than air. The gas inside a bubble is mostly water vapor, so it is also less dense than air.

The density of a gas can also be affected by its temperature. As the temperature of a gas increases, the molecules of the gas move faster. This causes them to spread out and become less dense. The opposite is also true. As the temperature of a gas decreases, the molecules of the gas move slower. This causes them to bunch together and become more dense.

The temperature of the gas inside a bubble is affected by the temperature of the water around it. The warmer the water, the warmer the gas inside the bubble. This means that the gas inside a bubble will be less dense if the water is warm than if the water is cold.

Recreation

Use in play

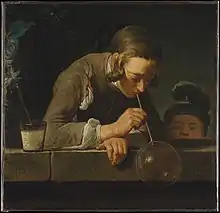

Soap bubbles have been used as entertainment for at least 400 years, as evidenced by 17th-century Flemish paintings showing children blowing bubbles with clay pipes. The London-based firm A. & F. Pears created a famous advertising campaign for its soaps in 1886 using a painting by John Everett Millais of a child playing with bubbles. The Chicago company Chemtoy began selling bubble solution in the 1940s, and bubble solution has been popular with children ever since. According to one industry estimate, retailers sell around 200 million bottles annually.

A woman creating bubbles with a long soap bubble wand

A woman creating bubbles with a long soap bubble wand Bubble Blowing at Dolores Park during Dyke March, June 2019

Bubble Blowing at Dolores Park during Dyke March, June 2019 Adriaen Hanneman, Two Boys Blowing Bubbles (ca. 1630)

Adriaen Hanneman, Two Boys Blowing Bubbles (ca. 1630) Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles (ca. 1734)

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Soap Bubbles (ca. 1734)

Colored bubbles

A bubble is made of transparent water enclosing transparent air. However, the soap film is as thin as the visible light wavelength, resulting in optical interference. This creates iridescence which, together with the bubble's spherical shape and fragility, contributes to its magical effect on children and adults alike. Each colour is the result of varying thicknesses of soap bubble film. Tom Noddy (who featured in the second episode of Marcus du Sautoy's The Code) gave the analogy of looking at a contour map of the bubbles' surface. However, it has become a challenge to produce artificially coloured bubbles.

Byron, Melody & Enoch Swetland invented a patented non-toxic bubble (Tekno Bubbles)[11] that glow under UV lighting. These bubbles look like ordinary high quality "clear" bubbles under normal lighting, but glow when exposed to true UV light. The brighter the UV lighting, the brighter they glow. The family sold them worldwide, but has since sold their company.

Adding coloured dye to bubble mixtures fails to produce coloured bubbles, because the dye attaches to the water molecules as opposed to the surfactant. Therefore, a colourless bubble forms with the dye falling to a point at the base. Dye chemist Dr. Ram Sabnis has developed a lactone dye that sticks to the surfactants, enabling brightly coloured bubbles to be formed. Crystal violet lactone is an example. Another man named Tim Kehoe invented a coloured bubble which loses its colour when exposed to pressure or oxygen, which he is now marketing online as Zubbles, which are non-toxic and non-staining. In 2010, Japanese astronaut Naoko Yamazaki demonstrated that it is possible to create coloured bubbles in microgravity. The reason is that the water molecules are spread evenly around the bubble in the low-gravity environment.

Freezing

If soap bubbles are blown into air that is below a temperature of −15 °C (5 °F), they will freeze when they touch a surface. The air inside will gradually diffuse out, causing the bubble to crumble under its own weight. At temperatures below about −25 °C (−13 °F), bubbles will freeze in the air and may shatter when hitting the ground. When a bubble is blown with warm air, the bubble will freeze to an almost perfect sphere at first, but when the warm air cools, and a reduction in volume occurs, there will be a partial collapse of the bubble. A bubble, created successfully at this low temperature, will always be rather small; it will freeze quickly and will shatter if increased further.[12] Freezing of small soap bubbles happens within 2 seconds after setting on snow (at air temperature around –10...–14 °C).[13]

Art

.JPG.webp)

Soap bubble performances combine entertainment with artistic achievement. They require a high degree of skill. Some performers use common commercially available bubble liquids while others compose their own solutions. Some artists create giant bubbles or tubes, often enveloping objects or even humans. Others manage to create bubbles forming cubes, tetrahedra and other shapes and forms. Bubbles are sometimes handled with bare hands. To add to the visual experience, they are sometimes filled with smoke, vapour or helium and combined with laser lights or fire. Soap bubbles can be filled with a flammable gas such as natural gas and then ignited.

Education

Bubbles can be effectively used to teach and explore a wide variety of concepts to even young children. Flexibility, colour formation, reflective or mirrored surfaces, concave and convex surfaces, transparency, a variety of shapes (circle, square, triangle, sphere, cube, tetrahedron, hexagon), elastic properties, and comparative sizing, as well as the more esoteric properties of bubbles listed on this page. Bubbles are useful in teaching concepts starting from 2 years old and into college years. A Swiss university professor, Dr. Natalie Hartzell, has theorized that the usage of artificial bubbles for entertainment purposes of young children has shown a positive effect in the region of the child's brain that controls motor skills and is responsible for coordination with children exposed to bubbles at a young age showing measurably better motion skills than those who were not.[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Hutchings, Michael; Morgan, Frank; Ritoré, Manuel; Ros, Antonio (July 17, 2000). "Proof of the double bubble conjecture". Electronic Research Announcements. 6 (6): 45–49. doi:10.1090/S1079-6762-00-00079-2. hdl:10481/32449.

- ↑ Jonathan Glancey, The Guardian November 28, 2012 Archived January 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Isenberg, Cyril (2012). "The Soap Film: An Analogue Computer". American Scientist. 100 (3): 1. doi:10.1511/2012.96.1.

- ↑ Isenberg, Cyril (1976). "The Soap Film: An Analogue Computer". American Scientist. 64 (3): 514–518. Bibcode:1976AmSci..64..514I. doi:10.1511/2012.96.1.

- ↑ Taylor, Jean E. (1977). "Soap Film Letters". American Scientist. 100 (January–February): 1. doi:10.1511/2012.96.1.

- ↑ New Scientist: What’s the best recipe for bubble mixture? Scientists have the answer 22 September 2022 By Chris Simms

- ↑ Teixeira, M.A.C.; Teixeira, P.I.C. (2009). "Contact angle of a hemispherical bubble: An analytical approach" (PDF). Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 338 (1): 193–200. Bibcode:2009JCIS..338..193T. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2009.05.062. PMID 19541324. S2CID 205804300.

- ↑ Arscott, Steve (2013). "Wetting of soap bubbles on hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and superhydrophobic surfaces". Applied Physics Letters. 102 (25): 254103. arXiv:1303.6414. Bibcode:2013ApPhL.102y4103A. doi:10.1063/1.4812710. S2CID 118645574.

- ↑ M.A.C. Teixeira, S. Arscott, S.J. Cox and P.I.C. Teixeira, Langmuir 31, 13708 (2015).

- ↑ "O despertar da bolha". Archived from the original on 2016-02-12. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ↑ Mary Bellis (1999-10-05). "Interview with Byron and Melody Swetland - The Inventors of Tekno Bubbles". Inventors.about.com. Archived from the original on 2013-07-04. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- ↑ Hope Thurston Carter: Frozen Frosted Fun Archived 2016-02-15 at the Wayback Machine hopecarter.photoshelter.com, Michigan, USA, 2014, retrieved 25 January 2017. – Photo catalogue.

- ↑ pilleuspulcher: Freezing soap bubbles on snow Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine google+, Regensburg, Germany, 23 January 2017, retrieved 25 January 2017. – Photos, description in German.

- ↑ Taylor, J. E. (1976). "The Structure of Singularities in Soap-Bubble-Like and Soap-Film-Like Minimal Surfaces". The Annals of Mathematics. 103 (3): 489–539. doi:10.2307/1970949. JSTOR 1970949.

Further reading

- Oprea, John (2000). The Mathematics of Soap Films – Explorations with Maple. American Mathematical Society (1st ed.). ISBN 0-8218-2118-0

- Boys, C. V. (1890) Soap-Bubbles and the Forces that Mould Them; (Dover reprint) ISBN 0-486-20542-8. Classic Victorian exposition, based on a series of lectures originally delivered "before a juvenile audience".

- Isenberg, Cyril (1992) The Science of Soap Films and Soap Bubbles ; (Dover) ISBN 0-486-26960-4.

- Noddy, Tom (1982) "Tom Noddy's Bubble Magic" Pioneer bubble performer's explanations created the modern performance art.

- Stein, David (2005) "How to Make Monstrous, Huge, Unbelievably Big Bubbles"; (Klutz) Formerly "The Unbelievable Bubble Book" (1987) it started the giant bubble sport. ISBN 978-1-57054-257-2

.jpg.webp)