| Hyades Cluster | |

|---|---|

Photograph of the Hyades Cluster | |

| Observation data (J2000.0 epoch) | |

| Right ascension | 4h 27m |

| Declination | +15° 52′ |

| Distance | 153 ly (47 pc[1][2][3][4]) |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 0.5 |

| Apparent dimensions (V) | 330′ |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mass | 400 M☉ |

| Radius | 10 light-years (core radius) |

| Estimated age | 625 million years |

| Closest open cluster | |

| Other designations | Caldwell 41, Cr 50, Mel 25 |

| Associations | |

| Constellation | Taurus |

The Hyades (/ˈhaɪ.ədiːz/; Greek Ὑάδες, also known as Caldwell 41, Collinder 50, or Melotte 25) is the nearest open cluster and one of the best-studied star clusters. Located about 153 light-years (47 parsecs)[1][2][3][4] away from the Sun, it consists of a roughly spherical group of hundreds of stars sharing the same age, place of origin, chemical characteristics, and motion through space.[1][5] From the perspective of observers on Earth, the Hyades Cluster appears in the constellation Taurus, where its brightest stars form a "V" shape along with the still-brighter Aldebaran. However, Aldebaran is unrelated to the Hyades, as it is located much closer to Earth and merely happens to lie along the same line of sight.

The five brightest member stars of the Hyades have consumed the hydrogen fuel at their cores and are now evolving into giant stars.[6] Four of these stars, with Bayer designations Gamma, Delta 1, Epsilon, and Theta Tauri, form an asterism that is traditionally identified as the head of Taurus the Bull.[6] The fifth of these stars is Theta1 Tauri, a tight naked-eye companion to the brighter Theta2 Tauri. Epsilon Tauri, known as Ain (the "Bull's Eye"), has a gas giant exoplanet candidate,[7] the first planet to be found in any open cluster.

The age of the Hyades is estimated to be about 625 million years.[1] The core of the cluster, where stars are the most densely packed, has a radius of 8.8 light-years (2.7 parsecs), and the cluster's tidal radius – where the stars become more strongly influenced by the gravity of the surrounding Milky Way galaxy – is 33 light-years (10 parsecs).[1] However, about one-third of confirmed member stars have been observed well outside the latter boundary, in the cluster's extended halo; these stars are probably in the process of escaping from its gravitational influence.[1]

Location and motion

The cluster is sufficiently close to the Sun that its distance can be directly measured by observing the amount of parallax shift of the member stars as the Earth orbits the Sun. This measurement has been performed with great accuracy using the Hipparcos satellite and the Hubble Space Telescope. An alternative method of computing the distance is to fit the cluster members to a standardized infrared color–magnitude diagram for stars of their type, and use the resulting data to infer their intrinsic brightness. Comparing this data to the brightness of the stars as seen from Earth allows their distances to be estimated. Both methods have yielded a distance estimate of 153 light-years (47 parsecs) to the cluster center.[1][2][3][4] The fact that these independent measurements agree makes the Hyades an important rung on the cosmic distance ladder method for estimating the distances of extragalactic objects.

The stars of the Hyades are more enriched in heavier elements than the Sun and other ordinary stars in the solar neighborhood, with the overall cluster metallicity measured at +0.14.[1] The Hyades Cluster is related to other stellar groups in the Sun's vicinity. Its age, metallicity, and proper motion coincide with those of the larger and more distant Praesepe Cluster,[8] and the trajectories of both clusters can be traced back to the same region of space, indicating a common origin.[9] Another associate is the Hyades Stream, a large collection of scattered stars that also share a similar trajectory with the Hyades Cluster. Recent results have found that at least 15% of stars in the Hyades Stream share the same chemical fingerprint as the Hyades cluster stars.[10] However, about 85% of stars in the Hyades Stream have been shown to be completely unrelated to the original cluster on the grounds of dissimilar age and metallicity; their common motion is attributed to tidal effects of the massive rotating bar at the center of the Milky Way galaxy.[11] Among the remaining members of the Hyades Stream, the exoplanet host star Iota Horologii has recently been proposed as an escaped member of the primordial Hyades Cluster.[12]

The Hyades are unrelated to two other nearby stellar groups, the Pleiades and the Ursa Major Stream, which are easily visible to the naked eye under clear dark skies.

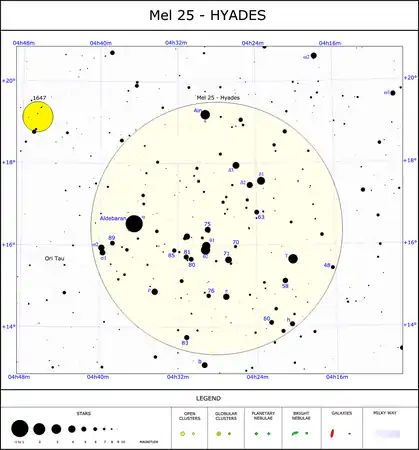

Star chart of the Hyades cluster

Star chart of the Hyades cluster.png.webp) Map of stars within 100 parsecs of the Sun, the Hyades is at 180° galactic longitude.

Map of stars within 100 parsecs of the Sun, the Hyades is at 180° galactic longitude.

Astrometry

A 2018 Gaia DR1 study of the Hyades Cluster determined a (U, V, W) group velocity of (−41.92 ± 0.16, −19.35 ± 0.13, −1.11 ± 0.11) km/sec, based on the space velocities of the 138 core stars. [13]

A 2019 Gaia DR2 study finds a (U, V, W) group velocity of (−42.24, −19.00, −1.48) km/sec, in very close agreement with the 2018 DR1 derivation. [14]

Another DR2 study from 2019 focused on mapping the 3D Topology & Velocities of the Hyades main body out to 30 parsecs, and included Sub-Stellar members as well. They identified 1764 member candidates, including 10 Brown Dwarfs and 17 White Dwarfs. The White Dwarfs included 9 single stars, and 4 binary systems. [15]

A 2022 Hyades study utilizing Gaia EDR3 derived a (U, V, W) group velocity of (-42.11±6.50, - 19.09±4.37, -1.32±0.44) km/sec, also with close agreement to DR1 and DR2 studies.[16]

History

Together with the other eye-catching open star cluster of the Pleiades, the Hyades form the Golden Gate of the Ecliptic, which has been known for several thousand years.

In Greek mythology, the Hyades were the five daughters of Atlas and half-sisters to the Pleiades. After the death of their brother, Hyas, the weeping sisters were transformed into a cluster of stars that was afterwards associated with rain.[17]

As a naked-eye object, the Hyades cluster has been known since prehistoric times. It is mentioned by numerous Classical authors from Homer to Ovid.[18] In Book 18 of the Iliad the stars of the Hyades appear along with the Pleiades, Ursa Major, and Orion on the shield that the god Hephaistos made for Achilles.[19]

In England the cluster was known as the "April Rainers" from an association with April showers, as recorded in the folk song "Green Grow the Rushes, O".

The cluster was probably first catalogued by Giovanni Battista Hodierna in 1654, and it subsequently appeared in many star atlases of the 17th and 18th centuries.[18] However, Charles Messier did not include the Hyades in his 1781 catalog of deep sky objects.[18] It therefore lacks a Messier number, unlike many other, more distant open clusters – e.g., M44 (Praesepe), M45 (Pleiades), and M67.

In 1869, the astronomer R.A. Proctor observed that numerous stars at large distances from the Hyades share a similar motion through space.[20] In 1908, Lewis Boss reported almost 25 years of observations to support this premise, arguing for the existence of a co-moving group of stars that he called the Taurus Stream (now generally known as the Hyades Stream or Hyades Supercluster). Boss published a chart that traced the scattered stars' movements back to a common point of convergence.[21]

By the 1920s, the notion that the Hyades shared a common origin with the Praesepe Cluster was widespread,[22] with Rudolf Klein-Wassink noting in 1927 that the two clusters are "probably cosmically related".[23] For much of the twentieth century, scientific study of the Hyades focused on determining its distance, modeling its evolution, confirming or rejecting candidate members, and characterizing individual stars.

Morphology and evolution

All stars form in clusters, but most clusters break up less than 50 million years after star formation concludes.[24] The astronomical term for this process is "evaporation." Only extremely massive clusters, orbiting far from the Galactic Center, can avoid evaporation over extended timescales.[25] As one such survivor, the Hyades Cluster probably contained a much larger star population in its infancy. Estimates of its original mass range from 800 to 1,600 times the mass of the Sun (M☉), implying still larger numbers of individual stars.[26][27]

Star populations

Theory predicts that a young cluster of this size should give birth to stars and substellar objects of all spectral types, from huge, hot O stars down to dim brown dwarfs.[27] However, studies of the Hyades show that it is deficient in stars at both extremes of mass.[5][28] At an age of 625 million years, the cluster's main sequence turn-off is about 2.3 M☉, meaning that all heavier stars have evolved into subgiants, giants, or white dwarfs, while less massive stars continue fusing hydrogen on the main sequence.[26] Extensive surveys have revealed a total of 8 white dwarfs in the cluster core,[29] corresponding to the final evolutionary stage of its original population of B-type stars (each about 3 M☉).[26] The preceding evolutionary stage is currently represented by the cluster's four red clump giants. Their present spectral type is K0 III, but all are actually "retired A stars" of around 2.5 M☉.[7][30][31] An additional "white giant" of type A7 III is the primary of θ2 Tauri, a binary system that includes a less massive companion of spectral type A; this pair is visually associated with θ1 Tauri, one of the four red giants, which also has an A-type binary companion.[30][32]

The remaining population of confirmed cluster members includes numerous bright stars of spectral types A (at least 21), F (about 60), and G (about 50).[1][28] All these star types are concentrated much more densely within the tidal radius of the Hyades than within an equivalent 10-parsec radius of the Earth. By comparison, our local 10-parsec sphere contains only 4 A stars, 6 F stars, and 21 G stars.[33]

The Hyades' cohort of lower-mass stars – spectral types K and M – remains poorly understood, despite proximity and long observation. At least 48 K dwarfs are confirmed members, along with about a dozen M dwarfs of spectral types M0-M2.[1][28][34] Additional M dwarfs have been proposed, but few are later than M3, and only about 12 brown dwarfs are currently reported.[5][35][36] This deficiency at the bottom of the mass range contrasts strongly with the distribution of stars within 10 parsecs of the Solar System, where at least 239 M dwarfs are known, comprising about 76% of all neighborhood stars.[33]

Mass segregation

The observed distribution of stellar types in the Hyades Cluster demonstrates a history of mass segregation. With the exception of its white dwarfs, the cluster's central two parsecs (6.5 light-years) contain only star systems of at least 1 M☉.[1] This tight concentration of heavy stars gives the Hyades its overall structure, with a core defined by bright, closely packed systems and a halo consisting of more widely separated stars in which later spectral types are common. The core radius is 2.7 parsecs (8.8 light-years, a little more than the distance between the Sun and Sirius), while the half-mass radius, within which half the cluster's mass is contained, is 5.7 parsecs (19 light-years). The tidal radius of ten parsecs (33 light-years) represents the Hyades' average outer limit, beyond which a star is unlikely to remain gravitationally bound to the cluster core.[1][26]

Stellar evaporation occurs in the cluster halo as smaller stars are scattered outward by more massive insiders. From the halo they may then be lost to tides exerted by the Galactic core or to shocks generated by collisions with drifting hydrogen clouds.[25] In this way the Hyades probably lost much of its original population of M dwarfs, along with substantial numbers of brighter stars.

Stellar multiplicity

Another result of mass segregation is the concentration of binary systems in the cluster core.[1][28] More than half of the known F and G stars are binaries, and these are preferentially located within this central region. As in the immediate Solar neighborhood, binarity increases with increasing stellar mass. The fraction of binary systems in the Hyades increases from 26% among K-type stars to 87% among A-type stars.[28] Hyades binaries tend to have small separations, with most binary pairs in shared orbits whose semimajor axes are smaller than 50 astronomical units.[37] Although the exact ratio of single to multiple systems in the cluster remains uncertain, this ratio has considerable implications for our understanding of its population. For example, Perryman and colleagues list about 200 high-probability Hyades members.[1] If the binary fraction is 50%, the total cluster population would be at least 300 individual stars.

Future evolution

Surveys indicate that 90% of open clusters dissolve less than 1 billion years after formation, while only a tiny fraction survive for the present age of the Solar System (about 4.6 billion years).[25] Over the next few hundred million years, the Hyades will continue to lose both mass and membership as its brightest stars evolve off the main sequence and its dimmest stars evaporate out of the cluster halo. It may eventually be reduced to a remnant containing about a dozen star systems, most of them binary or multiple, which will remain vulnerable to ongoing dissipative forces.[25]

Brightest stars

This is a list of Hyades cluster member stars that are fourth magnitude or brighter.[38]

| Designation | HD | Apparent magnitude |

Stellar classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theta2 Tauri | 28319 | 3.398 | A7III |

| Epsilon Tauri | 28305 | 3.529 | K0III |

| Gamma Tauri | 27371 | 3.642 | G8III |

| Delta1 Tauri | 27697 | 3.753 | G8III |

| Theta1 Tauri | 28307 | 3.836 | G7III |

| Kappa Tauri | 27934 | 4.201 | A7IV-V |

| 90 Tauri | 29388 | 4.262 | A6V |

| Upsilon Tauri | 28024 | 4.282 | A8Vn |

| Delta2 Tauri | 27962 | 4.298 | A2IV |

| 71 Tauri | 28052 | 4.480 | F0V |

Planets

Four stars in the Hyades have been found to host exoplanets. Epsilon Tauri has a superjovian planet, which was the first planet to be discovered in any open cluster.[7] HD 285507 has a hot Jupiter,[39] K2-25 has a Neptune-sized planet,[40] and K2-136 has a system of three planets.[41] Another star, HD 283869, may also host a planet, but this has not been confirmed as only one transit has been detected.[42]

In culture

In the works of Robert W. Chambers, H. P. Lovecraft, and others, the fictional city of Carcosa is located on a planet in the Hyades.

A 2018 archaeoastronomical paper suggested that the Hyades may have inspired the Norse myth of Ragnarök.[43] Astronomer Donald Olson questioned these findings, pointing out minor errors in the paper's astronomical data.[44]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Perryman, M.A.C.; et al. (1998). "The Hyades: distance, structure, dynamics, and age". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 331: 81–120. arXiv:astro-ph/9707253. Bibcode:1998A&A...331...81P.

- 1 2 3 van Leeuwen, F. "Parallaxes and proper motions for 20 open clusters as based on the new Hipparcos catalogue", A\&A, 2009

- 1 2 3 Majaess, D.; Turner, D.; Lane, D.; Krajci, T. "Deep Infrared ZAMS Fits to Benchmark Open Clusters Hosting delta Scuti Stars", Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, 2011

- 1 2 3 McArthur, Barbara E.; Benedict, G. Fritz; Harrison, Thomas E.; van Altena, William "Astrometry with the Hubble Space Telescope: Trigonometric Parallaxes of Selected Hyads", AJ, 2011

- 1 2 3 Bouvier J, Kendall T, Meeus G, Testi L, Moraux E, Stauffer JR, James D, Cuillandre J-C, Irwin J, McCaughrean MJ, Baraffe I, Bertin E. (2008) Brown dwarfs and very low mass stars in the Hyades cluster: a dynamically evolved mass function. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 481: 661-672. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008A%26A...481..661B.

- 1 2 Jim Kaler. "Hyadum I". Jim Kaler's Stars. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 Sato, Bun'ei; Izumiura, Hideyuki; Toyota, Eri; et al. (May 2007). "A Planetary Companion to the Hyades Giant ɛ Tauri". The Astrophysical Journal. 661 (1): 527–531. Bibcode:2007ApJ...661..527S. doi:10.1086/513503. S2CID 122683844.

- ↑ Dobbie, PD; Napiwotzki, R; Burleigh, MR; et al. (2006). "New Praesepe white dwarfs and the initial mass-final mass relation". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 369 (1): 383–389. arXiv:astro-ph/0603314. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.369..383D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10311.x. S2CID 17914736.

- ↑ "Messier Object 44". SEDS. 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

- ↑ De Silva, G; et al. (2011). "High-resolution elemental abundance analysis of the Hyades supercluster". MNRAS. 415 (1): 563–575. arXiv:1103.2588. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415..563D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18728.x. S2CID 56280307.

- ↑ Famaey B, Pont F, Luri X, Udry S, Mayor M, Jorissen A. (2007) The Hyades stream: an evaporated cluster or an intrusion from the inner disk? Astronomy & Astrophysics, 461: 957-962. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007A%26A...461..957F.

- ↑ Vauclair, S.; Laymand, M.; Bouchy, F.; Vauclair, G.; Hui Bon Hoa, A.; Charpinet, S.; Bazot, M. (2008). "The exoplanet-host star iota Horologii: an evaporated member of the primordial Hyades cluster". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 482 (2): L5–L8. arXiv:0803.2029. Bibcode:2008A&A...482L...5V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20079342. S2CID 18047352., announced in Emily Baldwin. "The Drifting Star". Archived from the original on 2008-04-21. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ Reino, Stella; de Bruijne, Jos; Zari, Eleonora; d'Antona, Francesca; Ventura, Paolo (2018-03-28). "A Gaia study of the Hyades open cluster". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 477 (3): 3197–3216. arXiv:1804.00759. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty793. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ↑ Röser, Siegfried; Schilbach, Elena; Goldman, Bertrand (2019-01-01). "Hyades tidal tails revealed by Gaia DR2". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 621: L2. arXiv:1811.03845. Bibcode:2019A&A...621L...2R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834608. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 118909033.

- ↑ Lodieu, N.; Smart, R. L.; Pérez-Garrido, A.; Silvotti, R. (2019-02-27). "A 3D view of the Hyades stellar and sub-stellar population". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 623: A35. arXiv:1901.07534. Bibcode:2019A&A...623A..35L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834045. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 119385406.

- ↑ Elsanhoury, Waleed; Al-Johani, Amnah; Al-anzi, Aneefah; Al-jaber, Bashayr; Al-Bishi, Fatmah; Kanaan, Nourah; Al-atwi, Ragwa; Al-khubrani, Reem; Al-anzi, Sarah (2022-03-16). "The Hyades Kinematical Structure with Gaia Era". Indian Journal of Pure & Applied Physics. 60 (3): 268–273. doi:10.56042/ijpap.v60i3.58781. ISSN 0975-1041. S2CID 251335023.

- ↑ Ian Ridpath. "The Hyades – the face of the bull". Ian Ridpath’s Star Tales. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 Information on the Hyades from SEDS

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Richmond Lattimore. University of Chicago Press, 1951.

- ↑ Zuckerman B, Song I. (2004) Young stars near the Sun. Annual Review of Astronomy & Astrophysics. Volume 42, 685-721. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2004ARA%26A..42..685Z.

- ↑ Boss L. (1908) Convergent of a moving cluster in Taurus. Astronomical Journal, 26: 31-36. Full text link at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1908AJ.....26...31B.

- ↑ Hertzsprung E. (1922) On the motions of Praesepe and of the Hyades. Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of the Netherlands, Vol. 1, p.150. Full text link at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1922BAN.....1..150H.

- ↑ Klein-Wassink WJ. (1927) The proper motion and the distance of the Praesepe cluster. Publications of the Kapteyn Astronomical Laboratory Groningen, 41: 1-48. Full text link at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1927PGro...41....1K

- ↑ Lada, CJ; Lada, EA (2003). "Embedded clusters in molecular clouds". Annual Review of Astronomy & Astrophysics. 41: 57–115. arXiv:astro-ph/0301540. Bibcode:2003ARA&A..41...57L. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.41.011802.094844. S2CID 16752089.

- 1 2 3 4 Pavani, DB; Bica, E (2007). "Characterization of open cluster remnants". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 468 (1): 139–150. arXiv:0704.1159. Bibcode:2007A&A...468..139P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20066240. S2CID 11609818.

- 1 2 3 4 Weideman V, Jordan S, Iben I, Casertano S. (1992) White dwarfs in the halo of the Hyades Cluster – The case of the missing white dwarfs. Astronomical Journal, 104: 1876-1891. 1992AJ....104.1876W.

- 1 2 Kroupa, P; Boily, CM (2002). "On the mass function of star clusters". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 336 (4): 1188–1194. arXiv:astro-ph/0207514. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.336.1188K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05848.x. S2CID 15225436.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Böhm-Vitense, E (2007). "Hyades morphology and star formation". Astronomical Journal. 133 (5): 1903–1910. Bibcode:2007AJ....133.1903B. doi:10.1086/512124.

- ↑ Böhm-Vitense E. (1995) White dwarf companions to Hyades F stars. Astronomical Journal, 110: 228-231. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1995AJ....110..228B.

- 1 2 Torres, G; Stefanik, RP; Latham, DW (1997). "The Hyades binaries Theta1 Tauri and Theta2 Tauri: The distance to the cluster and the mass-luminosity relation". Astrophysical Journal. 485 (1): 167–181. Bibcode:1997ApJ...485..167T. doi:10.1086/304422.

- ↑ Johnson JA, Fischer D, Marcy GW, Wright JT, Driscoll P, Butler RP, Hekker S, Reffert S, Vogt SS. (2007a) Retired A stars and their companions: Exoplanets orbiting three intermediate-mass subgiants. Astrophysical Journal, 665: 785-793. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007ApJ...665..785J.

- ↑ Armstrong, JT; Mozurkewich, D; Hajian, AR; et al. (2006). "The Hyades binary Theta2 Tauri: Confronting evolutionary models with optical interferometry". Astronomical Journal. 131 (5): 2643–2651. Bibcode:2006AJ....131.2643A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1000.4076. doi:10.1086/501429. S2CID 6268214.

- 1 2 Research Consortium on Nearby Stars (RECONS). Ten-parsec census at http://joy.chara.gsu.edu/RECONS/census.posted.htm.

- ↑ Endl, M; Cochran, WD; Kurster, M; Paulson, DB; Wittenmyer, RA; MacQueen, PJ; Tull, RG (2006). "Exploring the frequency of close-in Jovian planets around M dwarfs". Astrophysical Journal. 649 (1): 436–443. arXiv:astro-ph/0606121. Bibcode:2006ApJ...649..436E. doi:10.1086/506465. S2CID 14461746.

- ↑ Stauffer, JR; Balachandran, SC; Krishnamurthi, A; Pinsonneault, M; Terndrup, DM; Stern, RA (1997). "Rotational velocities and chromospheric activity of M dwarfs in the Hyades". Astrophysical Journal. 475 (2): 604–622. Bibcode:1997ApJ...479..776S. doi:10.1086/303930.

- ↑ Hogan E, Jameson R F, Casewell SL, Osbourne, SL, Hambly NC. (2008) L dwarfs in the Hyades. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 388 (2) 495-499. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008MNRAS.388..495H.

- ↑ Patience J, Ghez AM, Reid IN, Weinberger AJ, Matthews K. (1998) The multiplicity of the Hyades and its implications for binary star formation and evolution. Astronomical Journal, 115: 1972-1988. Abstract at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998AJ....115.1972P.

- ↑ Röser, S.; et al. (July 2011), "A deep all-sky census of the Hyades", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 531: 15, arXiv:1105.6093, Bibcode:2011A&A...531A..92R, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201116948, S2CID 118630215, A92. In the Vizier catalogue, sort on Vmag using '<4.51'. See also the linked entries in the All-sky Compiled Catalogue of 2.5 million stars (Kharchenko+ 2009).

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Quinn, Samuel N.; White, Russel J.; et al. (May 2014). "HD 285507b: An Eccentric Hot Jupiter in the Hyades Open Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 787 (1): 27. arXiv:1310.7328. Bibcode:2014ApJ...787...27Q. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/787/1/27. S2CID 118745790.

- ↑ Mann, Andrew W.; Gaidos, Eric; et al. (February 2016). "Zodiacal Exoplanets in Time (ZEIT). I. A Neptune-sized Planet Orbiting an M4.5 Dwarf in the Hyades Star Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 818 (1): 46. arXiv:1512.00483. Bibcode:2016ApJ...818...46M. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/818/1/46.

- ↑ Mann, Andrew W.; Vanderburg, Andrew; et al. (January 2018). "Zodiacal Exoplanets in Time (ZEIT). VI. A Three-planet System in the Hyades Cluster Including an Earth-sized Planet". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (1): 4. arXiv:1709.10328. Bibcode:2018AJ....155....4M. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa9791.

- ↑ Vanderburg, Andrew; Mann, Andrew W.; et al. (August 2018). "Zodiacal Exoplanets in Time (ZEIT). VII. A Temperate Candidate Super-Earth in the Hyades Cluster". The Astronomical Journal. 156 (2): 46. arXiv:1805.11117. Bibcode:2018AJ....156...46V. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aac894.

- ↑ Langer, Johnni (2018). "The Wolf's Jaw: an Astronomical Interpretation of Ragnarök". Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies. 6 (1) – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Ouellette, Jennifer (2018-11-16). ""Wolf's jaw" star cluster may have inspired parts of Ragnarök myth". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2022-06-09.

External links

- "Cl Melotte 25". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- Information on the Hyades from SEDS

- Astronomy Picture of the Day (2000-09-29)

- WEBDA open cluster database website for Hyades cluster – E. Paunzen (Univ. Vienna)

- Distance to the Hyades undergraduate lab Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine – J. Lucey (University of Durham)

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (medieval and early modern images of the Hyades)

- Hyades (star cluster) on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images