| Liliʻuokalani | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by James J. Williams, c. 1891 | |||||

| Queen of the Hawaiian Islands | |||||

| Reign | January 29, 1891 – January 17, 1893 | ||||

| Predecessor | Kalākaua | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy overthrown | ||||

| Born | Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha September 2, 1838 Honolulu, Oʻahu, Hawaiian Kingdom | ||||

| Died | November 11, 1917 (aged 79) Honolulu, Oʻahu, Territory of Hawaii | ||||

| Burial | November 18, 1917 | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| |||||

| House | Kalākaua | ||||

| Father |

| ||||

| Mother |

| ||||

| Religion | Protestantism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

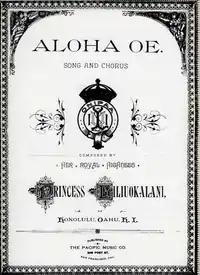

Liliʻuokalani (Hawaiian pronunciation: [liˌliʔuokəˈlɐni]; Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha; September 2, 1838 – November 11, 1917) was the only queen regnant and the last sovereign monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, ruling from January 29, 1891, until the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893. The composer of "Aloha ʻOe" and numerous other works, she wrote her autobiography Hawaiʻi's Story by Hawaiʻi's Queen during her imprisonment following the overthrow.

Liliʻuokalani was born in 1838 in Honolulu, on the island of Oʻahu. While her natural parents were Analea Keohokālole and Caesar Kapaʻakea, she was hānai (informally adopted) at birth by Abner Pākī and Laura Kōnia and raised with their daughter Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Baptized as a Christian and educated at the Royal School, she and her siblings and cousins were proclaimed eligible for the throne by King Kamehameha III. She was married to American-born John Owen Dominis, who later became the Governor of Oʻahu. The couple had no biological children but adopted several. After the accession of her brother David Kalākaua to the throne in 1874, she and her siblings were given Western style titles of Prince and Princess. In 1877, after her younger brother Leleiohoku II's death, she was proclaimed as heir apparent to the throne. During the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, she represented her brother as an official envoy to the United Kingdom.

Liliʻuokalani ascended to the throne on January 29, 1891, nine days after her brother's death. During her reign, she attempted to draft a new constitution which would restore the power of the monarchy and the voting rights of the economically disenfranchised. Threatened by her attempts to abrogate the Bayonet Constitution, pro-American elements in Hawaiʻi overthrew the monarchy on January 17, 1893. The overthrow was bolstered by the landing of US Marines under John L. Stevens to protect American interests, which rendered the monarchy unable to protect itself.

The coup d'état established the Republic of Hawaiʻi, but the ultimate goal was the annexation of the islands to the United States, which was temporarily blocked by President Grover Cleveland. After an unsuccessful uprising to restore the monarchy, the oligarchical government placed the former queen under house arrest at the ʻIolani Palace. On January 24, 1895, Liliʻuokalani was forced to abdicate the Hawaiian throne, officially ending the deposed monarchy. Attempts were made to restore the monarchy and oppose annexation, but with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, the United States annexed Hawaiʻi. Living out the remainder of her later life as a private citizen, Liliʻuokalani died at her residence, Washington Place, in Honolulu in 1917.

Early life

Liliʻuokalani was born Lydia Liliʻu Loloku Walania Kamakaʻeha[1][note 1] on September 2, 1838, to Analea Keohokālole and Caesar Kapaʻakea. She was born in the large grass hut of her maternal grandfather, ʻAikanaka, at the base of Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu.[3][note 2] According to Hawaiian custom, she was named after an event linked to her birth. At the time she was born, Kuhina Nui (regent) Elizabeth Kīnaʻu had developed an eye infection. She named the child using the words; liliʻu (smarting), loloku (tearful), walania (a burning pain) and kamakaʻeha (sore eyes).[5][1] She was baptized by American missionary Reverend Levi Chamberlain on December 23, and given the Christian name Lydia.[6][7]

Her family were of the aliʻi class of the Hawaiian nobility and were collateral relations of the reigning House of Kamehameha, sharing common descent from the 18th-century aliʻi nui (supreme monarch) Keaweʻīkekahialiʻiokamoku. From her biological parents, she descended from Keaweaheulu and Kameʻeiamoku, two of the five royal counselors of Kamehameha I during his conquest of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Kameʻeiamoku, the grandfather of both her mother and father, was depicted, along with his royal twin Kamanawa, on the Hawaiian coat of arms.[8] Liliʻuokalani referred to her family line as the "Keawe-a-Heulu line" after her mother's line.[9] The third surviving child of a large family, her biological siblings included: James Kaliokalani, David Kalākaua, Anna Kaʻiulani, Kaʻiminaʻauao, Miriam Likelike and William Pitt Leleiohoku II.[10] She and her siblings were hānai (informally adopted) to other family members. The Hawaiian custom of hānai is an informal form of adoption between extended families practiced by Hawaiian royals and commoners alike.[11][12] She was given at birth to Abner Pākī and his wife Laura Kōnia and raised with their daughter Bernice Pauahi.[13][14]

In 1842, at the age of four, she began her education at the Chiefs' Children's School (later known as the Royal School). She, along with her classmates, had been formally proclaimed by Kamehameha III as eligible for the throne of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[15] Liliʻuokalani later noted that these "pupils were exclusively persons whose claims to the throne were acknowledged."[16] She, along with her two older brothers James Kaliokalani and David Kalākaua, as well as her thirteen royal cousins, were taught in English by American missionaries Amos Starr Cooke and his wife, Juliette Montague Cooke.[17] The children were taught reading, spelling, penmanship, arithmetic, geometry, algebra, physics, geography, history, bookkeeping, music and English composition by the missionary couple who had to maintain the moral and sexual development of their charges.[18] Liliʻuokalani was placed with the youngest pupils of the class along with Princess Victoria Kamāmalu, Mary Polly Paʻaʻāina, and John William Pitt Kīnaʻu.[19] In later life, Liliʻuokalani would look back unfavorably on her early education remembering being "sent hungry to bed" and the 1848 measles epidemic that claimed the life of a classmate Moses Kekūāiwa and her younger sister Kaʻiminaʻauao.[17] The boarding school run by the Cookes was discontinued around 1850, so she, along with her former classmate Victoria, was sent to the relocated day school (also called Royal School) run by Reverend Edward G. Beckwith.[20] On May 5, 1853, she finished third in her final class exams behind Victoria and Nancy Sumner.[21] In 1865, after her marriage, she informally attended Oʻahu College (modern day Punahou School) and received instruction under Susan Tolman Mills, who later cofounded Mills College in California.[22]

Courtship and married life

After the boarding school was discontinued in 1850, Liliʻuokalani lived with her hānai parents at Haleʻākala, which she referred to in later life as her childhood home. Around this time, her hānai sister Pauahi married the American Charles Reed Bishop against the wishes of their parents but reconciled with them shortly before Pākī's death in 1855. Kōnia died two years afterward and Liliʻuokalani came under the Bishops' guardianship. During this period, Liliʻuokalani became a part of the young social elite under the reign of Kamehameha IV who ascended to the throne in 1855.[23] In 1856, Kamehameha IV announced his intent to marry Emma Rooke, one of their classmates. However, according to Liliʻuokalani, certain elements of the court argued "there is no other chief equal to you in birth and rank but the adopted daughter of Paki,"[24][note 3] which infuriated the King and brought the Queen to tears. Despite this upset, Liliʻuokalani was regarded as a close friend of the new Queen, and she served as a maid of honor during the royal wedding alongside Princess Victoria Kamāmalu and Mary Pitman.[26] At official state occasions, she served as an attendant and lady-in-waiting in Queen Emma's retinue. Visiting British dignitaries Lady Franklin and her niece Sophia Cracroft noted in 1861 that the "Honble. Lydia Paki" was "the highest unmarried woman in the Kingdom".[27]

Marriage consideration had begun early on for her. American merchant Gorham D. Gilman, a houseguest of the Pākīs, had courted her unsuccessfully when she was fifteen. Around the time of Kōnia's final illness in 1857, Liliʻuokalani was briefly engaged to William Charles Lunalilo. They shared an interest in music composition and had known each other from childhood. He had been betrothed from birth to Princess Victoria, the king's sister, but disagreements with her brothers prevented the marriage from materializing. Thus, Lunalilo proposed to Liliʻuokalani during a trip to Lahaina to be with Kōnia. A short-lived dual engagement occurred in which Liliʻuokalani was matched to Lunalilo and her brother Kalakaua to Princess Victoria. She ultimately broke off the engagement because of the urging of King Kamehameha IV and the opposition of the Bishops to the union.[28][note 4] Afterward, she became romantically involved with the American-born John Owen Dominis, a staff member for Prince Lot Kapuāiwa (the future Kamehameha V) and secretary to King Kamehameha IV. Dominis was the son of Captain John Dominis, of Trieste, and Mary Lambert Jones, of Boston. According to Liliʻuokalani's memoir, they had known each other from childhood when he watched the royal children from a school next to the Cookes'. During a court excursion, Dominis escorted her home despite falling from his horse and breaking his leg.[30]

.jpg.webp)

From 1860 to 1862, Liliʻuokalani and Dominis were engaged with the wedding set on her twenty-fourth birthday. This was postponed to September 16, 1862, out of respect for the death of Prince Albert Kamehameha, son of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma. The wedding was held at Haleʻākala, the residence of the Bishops. The ceremony was officiated by Reverend Samuel Chenery Damon in the Anglican rites. Her bridemaids were her former classmates Elizabeth Kekaʻaniau and Martha Swinton. King Kamehameha IV and other members of the royal family were honored guests. The couple moved into the Dominises' residence, Washington Place in Honolulu. Through his wife and connections with the king, Dominis would later become Governor of Oʻahu and Maui.[31] The union was reportedly an unhappy one with much gossip about Dominis' infidelities and domestic strife between Liliʻuokalani and Dominis' mother Mary who disapproved of the marriage of her son with a Hawaiian.[32] They never had any children of their own, but, against the wish of her husband and brother, Liliʻuokalani adopted three hānai children: Lydia Kaʻonohiponiponiokalani Aholo, the daughter of a family friend; Joseph Kaiponohea ʻAeʻa, the son of a retainer; and John ʻAimoku Dominis, her husband's son.[33][note 5]

After her marriage, she retained her position in the court circle of Kamehameha IV and later his brother and successor Kamehameha V. She assisted Queen Emma and King Kamehameha IV in raising funds to build The Queen's Hospital. In 1864, she and Pauahi helped Princess Victoria establish the Kaʻahumanu Society, a female-led organization aimed at the relief of the elderly and the ill. At the request of Kamehameha V, she composed "He Mele Lāhui Hawaiʻi" in 1866 as the new Hawaiian national anthem. This was in use until replaced by her brother's composition "Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī". During the 1869 visit of Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh and the Galatea, she entertained the British prince with a traditional Hawaiian luau at her Waikiki residence of Hamohamo.[35][4]

Heir apparent and regency

Elections of 1874

When Kamehameha V died in 1872 with no heir, the 1864 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom called for the legislature to elect the next monarch. Following a non-binding referendum and subsequent unanimous vote in the legislature, Lunalilo became the first elected king of Hawaii.[36] Lunalilo died without an heir in 1874. In the election that followed, Liliʻuokalani's brother, David Kalākaua, ran against Emma, the dowager queen of Kamehameha IV.[37] The choice of Kalākaua by the legislature, and the subsequent announcement, caused a riot at the courthouse. US and British troops were landed, and some of Emma's supporters were arrested. The results of the election strained the relationship between Emma and the Kalākaua family.[38][note 6]

After his accession, Kalākaua gave royal titles and styles to his surviving siblings, his sisters, Princess Lydia Kamakaʻeha Dominis and Princess Miriam Likelike Cleghorn, as well as his brother William Pitt Leleiohoku, whom he named heir to the Hawaiian throne as Kalākaua and Queen Kapiʻolani had no children of their own.[note 7] Leleiohoku died without an heir in 1877.[42] Leleiohoku's hānai (adoptive) mother, Ruth Keʻelikōlani, wanted to be named heir, but the king's cabinet ministers objected as that would place Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Ruth's first cousin, next in line.[43] This would put the Kamehamehas back in succession to the throne again, which Kalākaua did not wish. On top of that, Kalākaua's court genealogists had already cast doubt on Ruth's direct lineage, and in doing so placed doubt on Bernice's.[44] At noon on April 10, Liliʻuokalani became the newly designated heir apparent to the throne of Hawaii.[45] It was at this time that Kalākaua had her name changed to Liliʻuokalani (the "smarting of the royal ones"), replacing her given name of Liliʻu and her baptismal name of Lydia.[46] In 1878, Liliʻuokalani and Dominis sailed to California for her health. They stayed in San Francisco and Sacramento where she visited the Crocker Art Museum.[47][48]

First regency

During Kalākaua's 1881 world tour, Liliʻuokalani served as Regent in his absence.[49] One of her first responsibilities was handling the smallpox epidemic of 1881 likely brought to the islands by Chinese contracted laborers. After meeting her with her brother's cabinet ministers, she closed all the ports, halted all passenger vessels out of Oʻahu, and initiated a quarantine of the affected. The measures kept the disease contained in Honolulu and Oʻahu with only a few cases on Kauaʻi. The disease mainly affected Native Hawaiians with the total number of cases at 789 with 289 fatalities, or a little over thirty-six percent.[50][51][52]

It was during this regency that Liliʻuokalani visited the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on Molokaʻi in September.[53] She was too overcome to speak and John Makini Kapena, one of her brother's ministers, had to address the people on her behalf. After the visit, in the name of her brother, Liliʻuokalani made Father Damien a knight commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua for his service to her subjects. She also convinced the governmental board of health to set aside land for a leprosy hospital at Kakaʻako.[54] She made a second visit to the settlement with Queen Kapiʻolani in 1884.[55]

Liliʻuokalani was active in philanthropy and the welfare of her people. In 1886, she founded a bank for women in Honolulu named Liliuokalani's Savings Bank and helped Isabella Chamberlain Lyman establish Kumukanawai o ka Liliuokalani Hui Hookuonoono, a money lending group for women in Hilo. In the same year, she also founded the Liliʻuokalani Educational Society, an organization "to interest the Hawaiian ladies in the proper training of young girls of their own race whose parents would be unable to give them advantages by which they would be prepared for the duties of life." It supported the tuition of Hawaiian girls at Kawaiahaʻo Seminary for Girls, where her hānai daughter Lydia Aholo attended, and Kamehameha School.[56][57][58]

Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria

.jpg.webp)

In April 1887, Kalākaua sent a delegation to attend the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria in London. It included his wife Queen Kapiʻolani, the Princess Liliʻuokalani and her husband, as well as Court Chamberlain Colonel Curtis P. Iaukea acting as the official envoy of the King and Colonel James Harbottle Boyd acting as aide-de-camp to the Queen.[59] The party landed in San Francisco and traveled across the United States visiting Washington, D.C., Boston and New York City, where they boarded a ship for the United Kingdom. While in the American capital, they were received by President Grover Cleveland and his wife Frances Cleveland.[60] In London, Kapiʻolani and Liliʻuokalani received an official audience with Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. Queen Victoria greeted both Hawaiian royals with affection, and recalled Kalākaua's visit in 1881. They attended the special Jubilee service at Westminster Abbey and were seated with other foreign royal guests, and with members of the Royal Household.[61] Shortly after the Jubilee celebrations, they learned of the Bayonet Constitution that Kalākaua had been forced to sign under the threat of death. They canceled their tour of Europe and returned to Hawaii.[62]

Liliʻuokalani was approached on December 20 and 23 by James I. Dowsett, Jr. and William R. Castle, members of the legislature's Reform (Missionary) Party, proposing her ascension to the throne if her brother Kalākaua were removed from power. Historian Ralph S. Kuykendall stated that she gave a conditional "if necessary" response; however, Liliʻuokalani's account was that she firmly turned down both men.[63] In 1889, a part Native Hawaiian officer Robert W Wilcox, who resided in Liliʻuokalani's Palama residence, instigated an unsuccessful rebellion to overthrow the Bayonet Constitution.[64]

Second regency and death of Kalākaua

Kalākaua arrived in California aboard the USS Charleston on November 25, 1890. There was uncertainty as to the purpose of the king's trip. Minister of Foreign Affairs John Adams Cummins reported that the trip was solely for the king's health and would not extend beyond California, while local newspapers and the British commissioner James Hay Wodehouse speculated that the king might go further east to Washington, D.C., to negotiate a treaty to extend the existing exclusive US access rights to Pearl Harbor, or the annexation of the kingdom. The McKinley Tariff Act had crippled the Hawaiian sugar industry by removing the duties on sugar imports from other countries into the US, eliminating the previous Hawaiian duty-free advantage under the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875.[65][66] After failing to persuade the king to stay, Liliʻuokalani wrote that he and Hawaiian ambassador to the United States Henry A. P. Carter planned to discuss the tariff situation in Washington.[67] In his absence, Liliʻuokalani was left in charge as regent for the second time. In her memoir, she wrote that "Nothing worthy of record transpired during the closing days of 1890, and the opening weeks of 1891."[68]

Upon arriving in California, Kalākaua, whose health had been declining, stayed in a suite at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco.[69][70] Traveling throughout Southern California and Northern Mexico, the monarch suffered a stroke in Santa Barbara[71] and was rushed back to San Francisco. Kalākaua fell into a coma in his suite on January 18, and died two days later on January 20.[69][72] The official cause of death was "Bright's disease with Uremic Blood Poisoning."[73] The news of Kalākaua's death did not reach Hawaii until January 29 when the Charleston returned to Honolulu with the remains of the king.[74]

Reign

On January 29, 1891, in the presence of the cabinet ministers and the supreme court justices, Liliʻuokalani took the oath of office to uphold the constitution, and became the first and only female monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[75][76] The first few weeks of her reign were obscured by the funeral of her brother. After the end of the period of mourning, one of her first acts was to request the formal resignation of the holdover cabinet from her brother's reign. These ministers refused, and asked for a ruling by the Hawaii Supreme Court. All the justices but one ruled in favor of the Queen's decision, and the ministers resigned. Liliʻuokalani appointed Samuel Parker, Hermann A. Widemann, and William A. Whiting, and reappointed Charles N. Spencer (from the hold-over cabinet), as her new cabinet ministers. On March 9, with the approval of the House of Nobles, as required by the Hawaiian constitution, she named as successor her niece Kaʻiulani, the only daughter of Archibald Scott Cleghorn and her sister Princess Likelike, who had died in 1887.[77][78][79] From April to July, Liliʻuokalani paid the customary visits to the main Hawaiian Islands, including a third visit to the leper settlement at Kalaupapa. Historian Ralph Simpson Kuykendall noted, "Everywhere she was accorded the homage traditionally paid by the Hawaiian people to their alii."[80][81][82]

Following her accession, John Owen Dominis was given the title Prince Consort and restored to the Governorship of Oʻahu, which had been abolished following the Bayonet Constitution of 1887.[83][84] Dominis' death on August 27, seven months into her reign, greatly affected the new Queen. Liliʻuokalani later wrote: "His death occurred at a time when his long experience in public life, his amiable qualities, and his universal popularity, would have made him an adviser to me for whom no substitute could possibly be found. I have often said that it pleased the Almighty Ruler of nations to take him away from me at precisely the time when I felt that I most needed his counsel and companionship."[85][86][87] Cleghorn, her sister's widower, was appointed to succeed Dominis as Governor of Oʻahu. In 1892, Liliʻuokalani would also restore the positions of governor for the other three main islands for her friends and supporters.[88][83]

From May 1892 to January 1893, the legislature of the Kingdom convened for an unprecedented 171 days, which later historians such as Albertine Loomis and Helena G. Allen dubbed the "Longest Legislature".[89][90] This session was dominated by political infighting between and within the four parties: National Reform, Reform, National Liberal and Independent; none were able to gain a majority. Debates heard on the floor of the houses concerned the popular demand for a new constitution and the passage of a lottery bill and an opium licensing bill, aimed at alleviating the economic crisis caused by the McKinley Tariff. The main issues of contention between the new monarch and the legislators were the retention of her cabinet ministers, since political division prevented Liliʻuokalani from appointing a balanced council and the 1887 constitution gave the legislature the power to vote for the dismissal of her cabinet. Seven resolutions of want of confidence were introduced during this session, and four of her self-appointed cabinets (the Widemann, Macfarlane, Cornwell, and Wilcox cabinets) were ousted by votes of the legislature. On January 13, 1893, after the legislature dismissed the George Norton Wilcox cabinet (which had political sympathies to the Reform Party), Liliʻuokalani appointed the new Parker cabinet consisting of Samuel Parker, as minister of foreign affairs; John F. Colburn, as minister of the interior; William H. Cornwell, as minister of finance; and Arthur P. Peterson, as attorney general.[91] She chose these men specifically to support her plan of promulgating a new constitution while the legislature was not in session.[92]

Promulgating a new constitution

The precipitating event[93] leading to the 1893 overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was the attempt by Queen Liliʻuokalani to promulgate a new constitution to regain powers for the monarchy and Native Hawaiians that had been lost under the Bayonet Constitution. Her opponents, who were led by two Hawaiian citizens Lorrin A. Thurston and W. O. Smith and included six Hawaiian citizens, five US citizens and one German citizen,[94] were outraged by her attempt to promulgate a new constitution and moved to depose the Queen, overthrow the monarchy, and seek Hawaii's annexation to the United States.[note 8][96]

Shortly after her accession, Liliʻuokalani began to receive petitions to re-write the Bayonet Constitution[note 9] through the two major political parties of the time, Hui Kālaiʻāina and the National Reform Party.[note 10] Supported by two-thirds of the registered voters,[99] she moved to abrogate the existing 1887 constitution, but her cabinet withheld their support, knowing what her opponents' likely response would be.[note 11]

The proposed constitution (co-written by the Queen and two legislators, Joseph Nāwahī and William Pūnohu White) would have restored the power to the monarchy, and voting rights to economically disenfranchised native Hawaiians and Asians.[100][101] Her ministers and closest friends were all opposed to this plan; they tried unsuccessfully to dissuade her from pursuing these initiatives, both of which came to be used against her in the brewing constitutional crisis.[102]

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

.jpg.webp)

The political fallout led to citywide political rallies and meetings in Honolulu. Anti-monarchists, annexationists, and leading Reform Party politicians that included Lorrin A. Thurston, a grandson of American missionaries, and Kalākaua's former cabinet ministers under the Bayonet Constitution, formed the Committee of Safety in protest of the "revolutionary" action of the queen and conspired to depose her.[103] Thurston and the Committee of Safety derived their support primarily from the American and European business class residing in Hawaiʻi. Most of the leaders of the overthrow were American and European citizens who were also Kingdom subjects. They also included legislators, government officers, and a justice of the Hawaiian Supreme Court.[104][105]

In response, royalists and loyalists formed the Committee of Law and Order and met at the palace square on January 16, 1893. Nāwahī, White, Robert W. Wilcox, and other pro-monarchist leaders gave speeches in support for the queen and the government. To try to appease the instigators, the queen and her supporters abandoned attempts to unilaterally promulgate a constitution .[106][103]

The same day, the Marshal of the Kingdom, Charles Burnett Wilson, was tipped off by detectives to the imminent planned coup. Wilson requested warrants to arrest the 13-member council of the Committee of Safety, and put the Kingdom under martial law. Because the members had strong political ties to United States Minister to Hawaii John L. Stevens, the requests were repeatedly denied by the queen's cabinet, who feared that the arrests would escalate the situation. After a failed negotiation with Thurston,[107] Wilson began to collect his men for the confrontation. Wilson and captain of the Royal Household Guard Samuel Nowlein had rallied a force of 496 men who were kept at hand to protect the queen.[108] Marines from the USS Boston and two companies of US sailors landed and took up positions at the US Legation, the Consulate, and Arion Hall. The sailors and Marines did not enter the palace grounds or take over any buildings, and never fired a shot, but their presence served effectively in intimidating royalist defenders. Historian William Russ states, "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself".[109]

The queen was deposed on January 17, and the provisional government established under pro-annexation leader Sanford B. Dole was officially recognized by Stevens as the de facto government.[110][111][112] She temporarily relinquished her throne to the United States, rather than the Dole-led government, in hopes that the United States would restore Hawaii's sovereignty to the rightful holder.[113][114] The government under Dole began using ʻIolani Palace as its executive building.[115][116] A delegation departed for Washington, D.C., on January 19, to ask for immediate annexation by the United States.[117] At the request of the provisional government, Stevens proclaimed Hawaii a protectorate of the United States on February 1, to temporarily provide a buffer against domestic upheaval and interference by foreign governments.[118][119] The US flag was raised over the palace, and martial law was enforced. The annexation treaty presented to the US Senate contained a provision to grant Liliʻuokalani a $20,000 per annum lifetime pension, and Kaʻiulani a lump-sum payment of $150,000. The queen protested the proposed annexation in a January 19 letter to President Benjamin Harrison. She sent Prince David Kawānanakoa and Paul Neumann to represent her.[120]

Neumann delivered a letter from the queen to Grover Cleveland, who began his second non-consecutive term as president on March 4.[121] The Cleveland administration commissioned James Henderson Blount to investigate the overthrow. He interviewed those involved in the coup and wrote the Blount Report, and based on its findings, concluded that the overthrow of Liliʻuokalani was illegal, and that Stevens and American military troops had acted inappropriately in support of those who carried out the overthrow. On November 16, Cleveland sent his minister Albert S. Willis to propose a return of the throne to Liliʻuokalani if she granted amnesty to everyone responsible. Her first response was that Hawaiian law called for property confiscation and the death penalty for treason, and that only her cabinet ministers could put aside the law in favor of amnesty.[122][123][124] Liliuokalani's extreme position lost her the goodwill of the Cleveland administration.[125]

Cleveland sent the issue to the Congress, stating, "The Provisional Government has not assumed a republican, or other constitutional form, but has remained a mere executive council, or oligarchy, without the consent of the people".[126] The queen changed her position on the issue of amnesty, and on December 18, Willis demanded the provisional government reinstate her to the throne, but was refused. Congress responded with a US Senate investigation that resulted in the Morgan Report on February 26, 1894. It found Stevens and all parties except the queen "not guilty", absolving them of responsibility for the overthrow.[127] The provisional government formed the Republic of Hawaii on July 4 with Dole as its president, maintaining oligarchical control and a limited system of suffrage.[128]

Arrest and imprisonment

.jpg.webp)

At the beginning of January 1895, Robert W. Wilcox and Samuel Nowlein launched a rebellion against the forces of the Republic with the aim of restoring the queen and the monarchy. Its ultimate failure led to the arrest of many of the participants and other sympathizers of the monarchy. Liliʻuokalani was also arrested and imprisoned in an upstairs bedroom at the palace on January 16, several days after the failed rebellion, when firearms were found at her home of Washington Place after a tip from a prisoner.[129]

During her imprisonment, she abdicated her throne in return for the release (and commutation of the death sentences) of her jailed supporters; six had been sentenced to be hanged including Wilcox and Nowlein.[130] She signed the document of abdication on January 24. In 1898, Liliʻuokalani wrote:

For myself, I would have chosen death rather than to have signed it; but it was represented to me that by my signing this paper all the persons who had been arrested, all my people now in trouble by reason of their love and loyalty towards me, would be immediately released. Think of my position, – sick, a lone woman in prison, scarcely knowing who was my friend, or who listened to my words only to betray me, without legal advice or friendly counsel, and the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.

— Queen Liliʻuokalani, Hawaii's Story By Hawaii's Queen[131]

She was tried by the military commission of the Republic led by her former attorney general Whiting in the palace throne room on February 8. Defended at trial by another one of her former attorneys general Paul Neumann, she claimed ignorance but was sentenced to five years of hard labor in prison by the military tribunal and fined $5,000.[132][133][134] The sentence was commuted on September 4, to imprisonment in the palace, attended by her lady-in-waiting Eveline Townsend Wilson (aka Kitty), wife of Marshal Wilson.[135] In confinement she composed songs including "The Queen's Prayer" (Ke Aloha o Ka Haku – "The Grace of the Lord").[136]

On October 13, 1896, the Republic of Hawaii gave her a full pardon and restored her civil rights.[137] "Upon receiving my full release, I felt greatly inclined to go abroad," Liliʻuokalani wrote in her memoir.[138] From December 1896 through January 1897, she stayed in Brookline, Massachusetts, with her husband's cousins William Lee and Sara White Lee, of the Lee & Shepard publishing house.[139] During this period her long-time friend Julius A. Palmer Jr. became her secretary and stenographer, helping to write every letter, note, or publication. He was her literary support in the 1897 publication of the Kumulipo translation, and helped her in compiling a book of her songs. He assisted her as she wrote her memoir Hawaii's Story by Hawaii's Queen.[140] Sara Lee edited the book published in 1898 by Lee & Shepard.[141]

Annexation

.jpg.webp)

At the end of her visit in Massachusetts, Liliʻuokalani began to divide her time between Hawaii and Washington, D.C., where she worked to seek indemnity from the United States.[139]

She attended the inauguration of US President William McKinley on March 4, 1897, with a Republic of Hawaii passport personally issued to "Liliuokalani of Hawaii" by the republic's president Sanford B. Dole.[138] On June 16, McKinley presented the United States Senate with a new version of the annexation treaty, one that eliminated the monetary compensation for Liliʻuokalani and Kaʻiulani.[142] Liliʻuokalani filed an official protest with Secretary of State John Sherman the next day. The protest was witnessed by her agent and private secretary Joseph Heleluhe, Wekeki Heleluhe, and Captain Julius A. Palmer Jr., reported to be her American secretary.[143]

In June 1897 President McKinley signed the "Treaty for the Annexation for the Hawaiian Islands", but it failed to pass in the United States Senate after the Kūʻē Petitions were submitted by a commission of Native Hawaiian delegates consisting of James Keauiluna Kaulia, David Kalauokalani, William Auld, and John Richardson. Members of Hui Aloha ʻĀina collected over 21,000 signatures opposing an annexation treaty. Another 17,000 signatures were collected by members of Hui Kālaiʻāina but not submitted to the Senate because those signatures were also asking for restoration of the Queen. The petitions collectively were presented as evidence of the strong grassroots opposition of the Hawaiian community to annexation, and the treaty was defeated in the Senate— however, following its failure, Hawaii was annexed anyway via the Newlands Resolution, a joint resolution of Congress, in July 1898, shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War.[144][145][146]

As founder and head of the ʻOnipaʻa[147] movement Liliʻuokalani struggled fiercely against the annexation.[148] However, the annexation ceremony was held on August 12, 1898, at ʻIolani Palace, now being used as the executive building of the government. President Sanford B. Dole handed over "the sovereignty and public property of the Hawaiian Islands" to United States Minister Harold M. Sewall. The flag of the Republic of Hawaii was lowered and the flag of the United States was raised in its place.[149] Liliʻuokalani and her family members and retainers boycotted the event and shuttered themselves away at Washington Place. Many Native Hawaiians and royalists followed suit and refused to attend the ceremony.[150][151]

Crown Lands of Hawaii

Prior to the 1848 division of land known as the Great Māhele, during the reign of Kamehameha III, all land in Hawaii was owned by the monarchy. The Great Māhele subdivided the land among the monarchy, the government, and private ownership by tenants living on the land. What was reserved for the monarchy became known as the Crown Lands of Hawaii.[152] When Hawaii was annexed, the Crown Lands were seized by the United States government. The Queen gave George Macfarlane her power of attorney in 1898 as part of her legal defense team in seeking indemnity for the government's seizure of the Crown Lands. She filed a protest with the United States Senate on December 20, 1898, requesting their return and claiming the lands were seized without due process or recompense.[153]

That, the portion of the public domain heretofore known as Crown land is hereby declared to have been, on the twelfth day of August, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, and prior thereto, the property of the Hawaiian government, and to be free and clear from any trust of or concerning the same, and from all claim of any nature what soever, upon the rents, issues, and profits thereof. It shall be subject to alienation and other uses as may be provided by law.

– Hawaiian Organic Act, Sec. 99[154]

On April 30, 1900, the US Congress passed the Hawaii Organic Act establishing a government for the Territory of Hawaii.[155] The territorial government took control of the Crown Lands,[155] which became the source of the "Ceded Lands" issue in Hawaii.[156] The San Francisco Call reported on May 31 that Macfarlane had informed them the Queen had exhausted her patience with Congress and intended to file a lawsuit against the government.[157] Former United States Minister to Hawaii Edward M. McCook said he believed that once President McKinley began his second term on March 1, 1901, that the government would negotiate a generous settlement with Liliʻuokalani.[158]

During a 1900 Congressional deadlock, she departed for Honolulu with her Washington, D.C., physician Charles H. English (sometimes referred to as John H. English). Newspapers speculated that the Queen, having been diagnosed with cancer, was going home to die.[159] Historian Helena G. Allen made the case that English intended to gain title to crown lands for himself. According to Allen, the Queen balked at his draft of a settlement letter to Senator George Frisbie Hoar that he wanted her to copy in her handwriting and sign.[160] The doctor was terminated "without cause" a month after her return and sued her.[161]

The Pacific Commercial Advertiser lamented in 1903, "There is something pathetic in the appearance of Queen Liliuokalani as a waiting claimant before Congress." It detailed her years-long residencies in the nation's capital seeking indemnity, while legislators offered empty promises, but nothing of substance.[162]

Liliʻuokalani v. the United States

In 1909, Liliʻuokalani brought an unsuccessful lawsuit against the United States under the Fifth Amendment seeking the return of the Hawaiian Crown Lands.[155] The US courts invoked an 1864 Kingdom Supreme Court decision over a case involving the Dowager Queen Emma and Kamehameha V, using it against her. In this decision the courts found that the Crown Lands were not necessarily the private possession of the monarch in the strictest sense of the term.[163]

Later life and death

Although Liliʻuokalani was never successful in more than a decade of legal pursuits for recompense from the United States government for seized land, in 1911 she was finally granted a lifetime pension of $1,250 a month by the Territory of Hawaii. Historian Sydney Lehua Iaukea noted that the grant never addressed the question of the legality of the seizure itself, and the figure was greatly reduced from what she had requested for recompense.[164]

In April 1917, Liliʻuokalani raised the American flag at Washington Place in honor of five Hawaiian sailors who had perished in the sinking of the SS Aztec by German U-boats. Her act was interpreted by many as her symbolic support of the United States.[165] Subsequent historians have disputed the true meaning of her act; Neil Thomas Proto argued that "her gesture that day was intended to reflect the dignity with which she still held the right of her people to choose their own fate long after she was gone".[166]

By the end of that summer, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin reported that she was too frail to hold her birthday reception for the public, an annual tradition dating back to the days of the monarchy.[167] As one of her last public appearances in September, she officially became a member of the American Red Cross.[168] Following several months of deteriorating health that left her without the use of her lower limbs, as well as a diminished mental capacity rendering her incapable of recognizing her own house, her inner circle of friends and caregivers sat vigil for the last two weeks of her life knowing the end was near. In accordance with Hawaiian tradition, the royal kāhili fanned her as she lay in bed. On the morning of November 11, Liliʻuokalani died at the age of seventy-nine at her residence at Washington Place.[169]

The bells of Saint Andrew Cathedral and Kawaiahaʻo Church announced her death, tolling 79 times to signify her age. In keeping with Hawaiian tradition regarding deceased royalty, her body was not removed from her home until nearly midnight.[170] Her body lay in state at Kawaiahaʻo Church for public viewing, after which she received a state funeral in the throne room of Iolani Palace, on November 18. Composer Charles E. King led a youth choir in "Aloha ʻOe" as her catafalque was moved from the palace up Nuuanu Avenue with 1,200-foot ropes pulled by 200 people, for entombment with her family members in the Kalākaua Crypt at the Royal Mausoleum of Mauna ʻAla. The song was picked up by the procession participants and the crowds of people along the route.[171] Films were taken of the funeral procession and later stored at ʻĀinahau, the former residence of her sister and niece. A fire on August 1, 1921, destroyed the home and all its contents, including the footage of the Queen's funeral.[172]

Religious beliefs

Educated by American Protestant missionaries from a young age, Liliʻuokalani became a devout Christian and adherent to the principles of Christianity. These missionaries were largely of Congregationalist and Presbyterian extractions, subscribing to Calvinist theology, and Liliʻuokalani considered herself a "regular attendant on the Presbyterian worship".[173] She was the first member of the royal family to consistently and regularly attend service at Kawaiahaʻo Church since King Kamehameha IV converted to Anglicanism. On Sundays, she played the organ and led the choir at Kawaiahaʻo. She also regularly attended service at Kaumakapili Church and held a special interest in the Liliʻuokalani Protestant Church, to which she donated the Queen Liliʻuokalani Clock in 1892.[174]

Historian Helena G. Allen noted that Liliʻuokalani and Kalākaua "believed all religions had their 'rights' and were entitled to equal treatment and opportunities". Throughout her life, Liliʻuokalani showed a broad interest in the different Christian faiths including Catholicism, Mormonism, Episcopalianism and other Protestant denominations.[175] In 1896, she became a regular member of the Hawaiian Congregation at St. Andrew's Cathedral associated with the Reformed Catholic (Anglican/Episcopal) Church of Hawaii, which King Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma had founded.[176] During the overthrow and her imprisonment, Bishop Alfred Willis of St. Andrew's Cathedral had openly supported the Queen while Reverend Henry Hodges Parker of Kawaiahaʻo had supported her opponents.[177] Bishop Willis visited and wrote to her during her imprisonment and sent her a copy of the Book of Common Prayer.[178] Shortly after her release on parole, the former queen was baptized and confirmed by Bishop Willis on May 18, 1896, in a private ceremony in the presence of the sisters of St. Andrew's Priory.[179] In her memoir, Liliʻuokalani stated:

That first night of my imprisonment was the longest night I have ever passed in my life; it seemed as though the dawn of day would never come. I found in my bag a small Book of Common Prayer according to the ritual of the Episcopal Church. It was a great comfort to me, and before retiring to rest Mrs. Clark and I spent a few minutes in the devotions appropriate to the evening. Here, perhaps, I may say, that although I had been a regular attendant on the Presbyterian worship since my childhood, a constant contributor to all the missionary societies, and had helped to build their churches and ornament the walls, giving my time and my musical ability freely to make their meetings attractive to my people, yet none of these pious church members or clergymen remembered me in my prison. To this (Christian ?) conduct I contrast that of the Anglican bishop, Rt. Rev. Alfred Willis, who visited me from time to time in my house, and in whose church I have since been confirmed as a communicant. But he was not allowed to see me at the palace.[180]

She traveled to Utah in 1901 for a visit with Mormon president Joseph F. Smith, a former missionary to the Hawaiian Island. There she joined in services at the Salt Lake Tabernacle, and was feted at a Beehive House reception, attended by many expatriate Native Hawaiians.[181] In 1906, Mormon newspapers reported she had been baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by Elder Abraham Kaleimahoe Fernandez.[182] However, many historians doubt this claim, since the Queen herself never announced it. In fact, Liliʻuokalani continued to refer to herself as an Episcopalian in secular newspapers published the same week of her supposed Mormon baptism.[183] The Queen's interest in Mormonism later waned.[184]

The Queen was also remembered for her support of Buddhist and Shinto priests in Hawaii and became one of the first Native Hawaiians to attend a Buddha's Birthday celebration of May 19, 1901, at the Honwangji mission. Her attendance in the celebration helped Buddhism and Shinto gain acceptance into Hawaiian society and prevented the possible banning of the two religions by the Territorial government. Her presence was also widely reported in Chinese and Japanese newspapers throughout the world, and earned her the respect of many Japanese people both in Hawaii and in Japan itself.[185]

Compositions

Liliʻuokalani was an accomplished author and songwriter. Her book Hawaiʻi's Story by Hawaiʻi's Queen gave her view of the history of her country and her overthrow. She is said to have played guitar, piano, organ, ʻukulele and zither, and also sang alto, performing Hawaiian and English sacred and secular music.[186][187] In her memoirs she wrote:

To compose was as natural to me as to breathe; and this gift of nature, never having been suffered to fall into disuse, remains a source of the greatest consolation to this day.[…] Hours of which it is not yet in place to speak, which I might have found long and lonely, passed quickly and cheerfully by, occupied and soothed by the expression of my thoughts in music.[188]

Liliʻuokalani helped preserve key elements of Hawaiʻi's traditional poetics while mixing in Western harmonies brought by the missionaries. A compilation of her works, titled The Queen's Songbook, was published in 1999 by the Queen Liliʻuokalani Trust.[186][189] Liliʻuokalani used her musical compositions as a way to express her feelings for her people, her country, and what was happening in the political realm in Hawaiʻi.[190] One example of the way her music reflected her political views is her translation of the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant passed down orally by her great grandmother Alapaiwahine. While under house arrest, Liliʻuokalani feared she would never leave the palace alive, so she translated the Kumulipo in hopes that the history and culture of her people would never be lost.[191] The ancient chants record her family's genealogy back to the origin story of Hawaiʻi.[192]

After Liliʻuokalani was imprisoned in the ʻIolani Palace, she was denied literature and newspapers, essentially cutting her off from her people, but she continued to compose music with paper and pencil while she was in confinement.[193] Another of her compositions was "Aloha ʻOe", a song she had written previously and transcribed during her confinement. In her writings, she says, "At first I had no instrument, and had to transcribe the notes by voice alone; but I found, notwithstanding disadvantages, great consolation in composing, and transcribed a number of songs. Three found their way from my prison to the city of Chicago, where they were printed, among them the 'Aloha ʻOe' or 'Farewell to Thee', which became a very popular song."[193] Originally written as a lover's good-bye, the song came to be regarded as a symbol of, and lament for, the loss of her country. Today, it is one of the most recognizable Hawaiian songs.[190][194][195]

Legacy

Captain Julius A. Palmer Jr. of Massachusetts was her friend for three decades, and became her spokesperson when she was in residence at Boston and Washington, D.C., protesting the annexation of Hawaiʻi. In the nation's capital, he estimated that she had 5,000 visitors. When asked by an interviewer, "What are her most distinctive personal graces?", Palmer replied, "Above everything else she displayed a disposition of the most Christian forgiveness."[196] In covering her death and funeral, the mainstream newspapers in Hawaii that had supported the overthrow and annexation recognized that she had been held in great esteem around the world.[197] In March 2016, Hawaiʻi Magazine listed Liliʻuokalani as one of the most influential women in Hawaiian history.[194]

The Queen Liliʻuokalani Trust was established on December 2, 1909, for the care of orphaned and destitute children in Hawaii. Effective upon her death, the proceeds of her estate, with the exception of twelve individual inheritances specified therein, were to be used for the Trust.[198] The largest of these hereditary estates were willed to her hānai sons and their heirs: John ʻAimoku Dominis would receive Washington Place while Joseph Kaiponohea ʻAeʻa would receive Kealohilani, her residence at Waikiki. Both men predeceased the Queen.[199][200] Before and after her death, lawsuits were filed to overturn her will establishing the Trust. One notable litigant was Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, the nephew of her brother Kalākaua and his wife Kapiʻolani and Liliʻuokalani's second cousin,[note 12] who brought a suit against the Trust on November 30, 1915, questioning the Queen's competency in executing the will and attempting to break the Trust. These lawsuits were resolved in 1923 and the will went into probate.[203][204] The Queen Liliʻuokalani Children's Center was created by the Trust.[205][206]

Liliʻuokalani and her siblings are recognized by the Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame as Na Lani ʻEhā (The Heavenly Four) for their patronage and enrichment of Hawaii's musical culture and history.[207][208] In 2007, Honolulu magazine rated "Aloha ʻOe" as the greatest song in the history of Hawaiian music.[195] Songwriter Charles E. King, known as the composer of "Ke Kali Nei Au", was tutored in music by her.[209] Entertainer Bina Mossman led the Bina Mossman Glee Club that rehearsed regularly at Washington Place, while Liliʻuokalani helped them with pronunciation of the Hawaiian language. At the queen's funeral, the glee club was part of the kahili bearers who stood watch over the coffin for two hours at a time, waving the kahilis and singing Liliʻuokalani's compositions.[210][211]

The annual Queen Liliʻuokalani Outrigger Canoe Race, which follows an 18-mile course from Kailua Bay to Honaunau Bay, was organized in 1972 as an endurance training course for men, in preparation for the traditional Molokaʻi to Oʻahu canoe races. Women canoe teams were added in 1974. The race is held over Labor Day Weekend each year to coincide with Liliʻuokalani's birthday on September 2.[212]

In the 2001 naming of the "Queen Liliʻuokalani Center for Student Services", on the University of Hawaii at Manoa campus, the Board of Regents noted, "As the last Hawaiian monarch, Queen Liliʻuokalani symbolizes an important link to traditional Hawaiian culture and society. Her influence is well understood, widely respected and has been a strong motivating factor in the widespread emergence of Hawaiian culture and the values embodied in it."[213]

In 2017, Edgy Lee researched and filmed Liliuokalani – Reflections of Our Queen, a documentary looking at the legacy of the queen in Hawaii. A showing at Washington Place fundraised for the museum.[58] Liliʻuokalani and the overthrow have been subject of documentaries including The American Experience: Hawaii's Last Queen (1994) and Conquest of Hawaii (2003).[214][215][216]

Numerous hula events are held to honor her memory, including the Queen Liliʻuokalani Keiki Hula Competition Honolulu, organized in 1976.[217] The County of Hawaii holds an annual He Hali'a Aloha no Lili'uokalani Festival, Queen's Birthday Celebration at Liliʻuokalani Park and Gardens in Hilo, in partnership with the Queen Lili'uokalani Trust. The event begins with several hundred dancers showered by 50,000 orchid blossoms.[218]

Titles, styles and arms

Titles and styles

- 1838 – September 16, 1862: The Honorable Miss Lydia Kamakaʻeha Pākī[27][31][219]

- September 16, 1862 – 1874: The Honorable Mrs. Lydia Kamakaʻeha Dominis[220]

- 1874 – April 10, 1877: Her Royal Highness The Princess Lydia Kamakaʻeha Dominis[221][222][note 13]

- April 10, 1877 – January 29, 1891: Her Royal Highness The Princess Liliʻuokalani, Heir Apparent[223][note 14]

- January 20, 1881 – October 29, 1881, and November 25, 1890 – January 29, 1891: Her Royal Highness The Princess Regent[225]

- January 29, 1891 – January 17, 1893: Her Majesty The Queen[226]

Regalia

|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

| Monogram of Queen Liliʻuokalani | Coat of arms of the Kalākaua Dynasty | Monogram of Queen Liliʻuokalani (variant) |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Liliʻuokalani | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Family tree

|

Key- (k)= Kane (male/husband) |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Other source gives her the additional name of "Wewehi" which has no translation in relation to her birth.[2]

- ↑ The area was traditionally referred to as Mana, Manamana, Honolulu and later became the site of The Queen's Hospital.[4]

- ↑ According to American Commissioner to Hawaii, David L. Gregg, "Pakea [sic] was more unequivocal in his condemnation of the match. He expressed his opinion that his daughter Lydia Paki was more eligible, but declared that if neither the King nor any high chief thought proper to marry her, he would have her married to some good white man, which after all might be much more for her good."[25]

- ↑ Historian Helena G. Allen noted that this "would undoubtedly been a disasterous [sic] marriage".[29]

- ↑ John Dominis ʻAimoku formally changed his surname to Dominis in 1910.[34]

- ↑ Historian George Kanahele noted that the rift was largely between Liliʻuokalani and Emma since her brother actively sought reconciliation with the dowager queen. During the coronation of Kalākaua, Queen Emma was given greater precedence over Liliʻuokalani and her husband, an action that infuriated Liliʻuokalani.[39]

- ↑ Allen noted, "According to Thrum's Annual, two new princesses were designated: 'Princess Likelike and Princess Kamakaeha Dominis.' There is no evidence of an official act on the part of Kalakaua [at this time]."[40] On February 10, 1883, Kalākaua officially created her a Princess of the Kingdom by Letters Patent along with other members of his family who been using their courtesy titles for the years between 1873 and 1883.[41]

- ↑ "W.D. Alexander (History of Later Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy and the Revolution of 1893, Alexander 1896, p. 37) gives the following as the wording of Thurston's motion [to launch the coup]: 'That preliminary steps be taken at once to form and declare a Provisional Government with a view to annexation to the United States.' Thurston later wrote that his motion was 'substantially as follows: "I move that it is the sense of this meeting that the solution of the present situation is annexation to the United States."'(Memoirs, p. 250) Lt. Lucien Young (The Boston at Hawaii, p. 175) gives the following version of the motion: 'Resolved, That it is the sense of this committee that in view of the present unsatisfactory state of affairs, the proper course to pursue is to abolish the monarchy and apply for annexation to the United States.'"[95]

- ↑ The Bayonet Constitution was named because it had been signed by the previous monarch under threat of violence from a militia composed of armed American and Europeans calling themselves the "Honolulu Rifles".[97]

- ↑ "She ... defended her act[ions] by showing that, out of a possible 9,500 native voters in 1892, 6,500 asked for a new Constitution."[98]

- ↑ The Queen's new cabinet "had been in office less than a week, and whatever they thought about the need for a new constitution ... they knew enough about the temper of the queen's opponents to realize that they would endure the chance to challenge her, and no minister of the crown could look forward ... to that confrontation".[100]

- ↑ Although Liliʻuokalani referred to Kūhiō as her second cousin, Kūhiō was actually her first cousin once removed.[201][202]

- ↑ Information on Liliʻuokalani's titles and styles from 1874 to 1893 is from the yearly editions of the Hawaiian Almanac and Annual, all edited by Thomas G. Thrum and published by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Abbreviated citations are provided to indicate the specific editions used.

- ↑ She was referred to as Crown Princess of Hawaii while in England, although this was never one of her official titles.[224]

Citations

- 1 2 Haley 2014, p. 232; Allen 1982, p. 36; Siler 2012, p. 32

- ↑ Morris 1993, p. x.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 1–4; Allen 1982, p. 33

- 1 2 Kanahele 1999, p. 105; "La Hanau o ke Kama Aliiwahine Liliu". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. Vol. XIV, no. 36. Honolulu. September 4, 1875. p. 2. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Pukui & Elbert 1986, pp. 38, 206, 211. 224, 381.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 40; Cooke & Cooke 1937, p. 20

- ↑ Chamberlain, Levi (July 21, 1842). "Journal of Levi Chamberlain" (PDF). 23. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 1–2, 104–105, 399–409; Pratt 1920, pp. 34–36; Allen 1982, pp. 33–36; Haley 2014, p. 96; Gregg 1982, pp. 316–317, 528, 571, 581

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 104–105; Kuykendall 1967, p. 262; Osorio 2002, p. 201; Van Dyke 2008, p. 96

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 399.

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ King & Roth 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Hodges 1918, p. 13.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ "CALENDAR: Princes and Chiefs eligible to be Rulers". The Polynesian. Vol. 1, no. 9. Honolulu. July 20, 1844. p. 1, col. 3. Archived from the original on March 11, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.; Cooke & Cooke 1937, pp. v–vi; Van Dyke 2008, p. 364; Pratt 1920, pp. 52–55

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 5

- 1 2 Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 5–9; Allen 1982, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, pp. 23–39; Kanahele 2002, pp. 21–54; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 5–9; Allen 1982, pp. 47–68

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, pp. 30–34.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 9; Allen 1982, p. 72

- ↑ Topolinski 1975, pp. 32–34, 38.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 109–110.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 69–84; King & Roth 2006, p. 21; Taylor, Albert Pierce (June 12, 1910). "Court Beauties of Fifty Years Ago". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. VII, no. 388. Honolulu. p. 13. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 12

- ↑ Gregg 1982, pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 81–84; Kanahele 1999, pp. 60–62; "His Majesty's Marriage". The Polynesian. Vol. XIII, no. 7. Honolulu. June 21, 1856. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017.; "Marriage Of His Majesty Kamehameha IV". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. 1, no. 1. Honolulu. July 2, 1856. Image 2, col. 4. Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- 1 2 Cracroft, Franklin & Queen Emma 1958, pp. 111–112

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 77, 84–89; Haley 2014, p. 217; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 89.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 52, 84–89; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 11–13, 16

- 1 2 Allen 1982, pp. 84–89, 98–99, 103–104; Kanahele 2002, p. 97; "Notes of the Week". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. VII, no. 12. Honolulu. September 18, 1862. Image 2, col. 5. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "Marela". Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. Vol. I, no. 43. Honolulu. September 20, 1862. p. 3. Retrieved September 26, 2016.; "Na Mea Mare". Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika. Vol. II, no. 52. Honolulu. September 18, 1862. p. 2. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 109–153, 159–161; Haley 2014, p. 200; Blount 1895, p. 996

- ↑ Bonura & Witmer 2013, pp. 109–115.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 91–98–99, 116–117, 122–123; Smith 1956, pp. 8–10

- ↑ Kuykendall 1953, pp. 239–245; "Death of the King". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XVII, no. 24. Honolulu. December 14, 1872. Image 2, col. 2. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "Meeting of the Assembly! Election of Prince Lunalilo As King! Immense Enthusiasm!". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XVII, no. 28. Honolulu. January 11, 1873. Image 4, col. 4. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "The Accession to the Throne". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XVII, no. 28. Honolulu. January 11, 1873. Image 3, Col. 4. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 3–16.

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, pp. 315–319; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 40–41, 45–49

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, p. 318, 353–354.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 138.

- ↑ "By Authority". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Honolulu. February 17, 1883. Image 5. col. 1. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Kanahele 1999, p. 318.

- ↑ Kanahele 2002, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 53–55; Kanahele 2002, pp. 151–152; "The Heir Apparent". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XXI, no. 42. Honolulu. April 14, 1877. Image 2, col. 2. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "Proclamation of the Heir Apparent". The Hawaiian Gazette. Vol. XIII, no. 16. Honolulu. April 18, 1877. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 147.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 61–68.

- ↑ "The Hawaiian Princess". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco. April 13, 1878. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 227; Liliuokalani 1898, p. 75–85; Middleton 2015, p. 530

- ↑ Dye 1997, pp. 171–177.

- ↑ Thrum 1882, p. 66.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1886, p. 79.

- ↑ Inglis 2013, pp. 130; Law 2012, p. 125

- ↑ Law 2012, p. 125

- ↑ Inglis 2013, pp. 88–89; Liliuokalani 1886, pp. iii–xvii

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Bonura & Witmer 2013, pp. 120–121.

- 1 2 Hawe, Jeff (August 7, 2018). "Ahead of Her Time". Hawaii Business Magazine. Honolulu. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ↑ Iaukea 2012, p. 30; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 341

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 340–343; Liliuokalani 1898, p. 116–176

- ↑ Iaukea 2012, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 171–176; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 340–343

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 415; Liliuokalani 1898, p. 186–188

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 191–201; Siler 2012, p. 176; Kuykendall 1967, pp. 424–432

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 466–469.

- ↑ Spickard, Rondilla & Wright 2002, p. 316.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 470–474; Krout 1898, p. 10; Thrum 1892, p. 126; Dando-Collins 2014, p. 42; Allen 1982, pp. 225–226; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 206–207

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 470; Allen 1982, pp. 225–229; Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 206–209

- 1 2 Dando-Collins 2014, p. 42.

- ↑ Rego, Nilda (April 25, 2013). "Days Gone By: 1890: Hawaii's King Kalakaua visits San Francisco". The Mercury News. San Francisco. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 472.

- ↑ Vowell 2011, p. 91.

- ↑ Mcdermott, Choy & Guerrero 2015, p. 59.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 473–474.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 474–76.

- ↑ "By Authority". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. XV, no. 25. Honolulu. January 30, 1891. Image 2, col. 1. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 476–78.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 245.

- ↑ "The Succession Princess Kaiulani Proclaimed Successor to the Hawaiian Throne". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. XV, no. 57. Honolulu. March 9, 1891. Image 2, col. 2. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 484.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 246–53.

- ↑ Inglis 2013, p. 136.

- 1 2 Newbury 2001, pp. 16, 29–30.

- ↑ "By Authority". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. XV, no. 51. Honolulu. March 2, 1891. Image 2, col. 1. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 255–58.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 486–86.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 29, 220–25.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 485–86.

- ↑ Loomis 1963, pp. 7–27.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 269–70.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 562–563, 573–581; Allen 1982, p. 174–175; Moblo 1998, pp. 229–232; "A New Cabinet – Some New Ministers for the Public to Swallow". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XVII, no. 3277. Honolulu. January 14, 1893. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 581–583

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 582.

- ↑ Blount 1895, p. 588.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 587–588.

- ↑ Russ 1959, p. 90.

- ↑ Lee 1993, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Russ 1959, p. 67.

- ↑ Lobo, Talbot & Carlston 2016, p. 122.

- 1 2 Daws 1968, p. 271.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 582–586.

- ↑ Blount 1895, p. 496.

- 1 2 Kuykendall 1967, pp. 586–594; Alexander 1896, pp. 37–51

- ↑ Twigg-Smith 1998, pp. 135–166.

- ↑ Andrade 1996, p. 130.

- ↑ "Popular Meeting – Over Two Thousand Person Assemble on Palace Square – They Pass a Resolution Upholding the Queen and the Government". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. January 17, 1893. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017.

- ↑ Twombly 1900, p. 333.

- ↑ Young 1899, p. 252.

- ↑ Russ 1959, p. 350

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, pp. 387–388.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 294.

- ↑ Alexander 1896, p. 65.

- ↑ Tabrah 1984, p. 102.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 603.

- ↑ Alexander 1896, p. 66.

- ↑ Siler 2012, p. 250.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 605–610.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 599–605.

- ↑ Alexander 1896, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Alexander 1896, pp. 71–76.

- ↑ Alexander 1896, p. 74.

- ↑ Calhoun 1988, p. 150.

- ↑ Love 2005, p. 112.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, p. 642.

- ↑ Warren Zimmermann (2004). First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made Their Country a World Power. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 290. ISBN 9780374528935. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ↑ "Hawaiian Situation: The President's Message to Congress". The National Tribune. Washington D.C. December 21, 1893. p. 8, col. 4. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 642–45.

- ↑ Kuykendall 1967, pp. 649–50.

- ↑ "Queen Arrested". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. IX, no. 1238. Honolulu. January 16, 1895. Image 3. col. 1. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "She Plotted". The Hawaiian Star. Vol. III, no. 557. Honolulu. January 17, 1895. p. 3, col. 2. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Siler 2012, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ Liliuokalani 1898, p. 274.

- ↑ Proto 2009, pp. 93–112.

- ↑ Siler 2012, p. 268.

- ↑ Borch 2014, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 123, 147, 187, 344–345, 347; "Declines to Confess". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. IX, no. 1256. Honolulu. February 6, 1895. p. 5, col. 2. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "Five Years in Parlor". The Daily Bulletin. Vol. IX, no. 1274. Honolulu. February 27, 1895. p. 5, col. 2. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Siler 2012, p. 274.

- ↑ Siler 2012, pp. 276–279.

- 1 2 Liliuokalani 1898, p. 305.

- 1 2 "A PACIFIC CABLE: Liliuokalani is in Boston". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XXV, no. 4507. Honolulu. January 15, 1897. Image 1, col. 2. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "PRIVATE AFFAIRS: Liliuokalani and Capt. Palmer to Work McKinley". Hawaiian Gazette. Vol. XXXII, no. 19. Honolulu. March 5, 1897. Image 1, col. 6. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Julius A. Palmer's Story". The Independent (reprinted from The Boston Globe). September 29, 1897. Image 1, cols. 1–2; Image 4, cols. 3–5. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 356–359.

- ↑ "Treaty to Annex Hawaii". The Times. No. 1185. Washington, D.C. June 17, 1897. Image 1, col. 3. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "Treaty to Annex Hawaii". The Times. No. 1185. Washington, D.C. June 17, 1897. Image 2, col. 4. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "By the Ex-Queen: Protest Made to the Annexation of Hawaii. An Appeal for Restoration. Authority of Present Government Denied. Document Signed in Washington and 'Julius' Witnessed the Signature". Hawaiian Gazette. Vol. XXXII, no. 55. Honolulu. July 9, 1897. Image 1, Col. 6. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "The Ex-Queen's Protest". The Times. No. 1186. Washington, D.C. June 18, 1897. Image 1, col. 7. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Haley 2014, pp. 317–336.

- ↑ Silva 2004, pp. 123–163; Silva, Noenoe K. (1998). "The 1897 Petitions Protesting Annexation". The Annexation Of Hawaii: A Collection Of Document. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ↑ Mehmed 1998, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of ʻonipaʻa". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ ‘Onipa‘ a movement. in: Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ Haley 2014, pp. 336.

- ↑ Allen 1982, p. 365.

- ↑ Mehmed 1998, pp. 141–144.

- ↑ Linnekin 1983, p. 173.

- ↑ "HAWAII'S EX-QUEEN: Protests Against the Seizure of Her Property". The Herald. Vol. 26, no. 82. Los Angeles. December 21, 1898. Image 1. col. 3. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Thorpe 1909, p. 903

- 1 2 3 Parker 2007, p. 205.

- ↑ Parker 2007, pp. 205–207.

- ↑ Proto 2009, p. 132; "Hawaiian Queen Decides to Sue for Crown Lands". The San Francisco Call. Vol. LXXXVII, no. 192. San Francisco. May 31, 1900. Image 12, col. 1. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Claims of Ex-Queen". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XXXII, no. 5589. Honolulu. July 5, 1903. p. 10, col. 2. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Ex-Queen Liliuokalani Is Here on Her Way to Hawaii". San Francisco Chronicle. Vol. LXXI, no. 125. San Francisco. May 20, 1900. p. 1, col. 1. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved October 15, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.; "Ex-Queen Here Soon". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XXXI, no. 5559. Honolulu. May 31, 1900. p. 5, col. 3. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Allen 1982, pp. 330–361, 368–369

- ↑ "Court Notes". The Independent. Vol. XI, no. 1586. Honolulu. August 16, 1900. p. 4. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.; "Dr. English's Suit Against Liliuokalani". The Honolulu Republican. Vol. I, no. 71. Honolulu. September 5, 1900. Image 8, col. 3. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Liliuokalani's Claim". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser. Vol. XXXVII, no. 6399. Honolulu. February 10, 1903. Image 4, col. 1. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Banner 2009, p. 161.

- ↑ Iaukea 2012, pp. 86, 181; "Queen's Pension is Approved". Evening Bulletin. Honolulu. March 30, 1911. p. 2, col. 3. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Abbott, Lyman; Mabie, H. W., eds. (May 30, 1917). "An American Queen". The Outlook. Vol. 116, no. 5. New York. pp. 177–178. OCLC 5361126. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017.; "Elima Keiki Hawaii i Make". Ke Aloha Aina. Vol. XXII, no. 14. Honolulu. April 6, 1917. p. 1. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ↑ Proto 2009, p. 207

- ↑ "Queen Not to Hold Reception". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. August 29, 1917. p. 10, col. 5. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.; "The Queen's Birthday". The Daily Bulletin. Honolulu. September 3, 1892. Image 3, col. 2. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Liliuokalani Becomes a Red Cross Member as Whistles Signify 8000 Mark is Reached". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. September 29, 1917. p. 2, col. 2–5. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ↑ Hodges 1918, pp. 35–37; Allen 1982, p. 396

- ↑ "Death Comes to Hawaii's Queen in Calm of Sabbath Morning". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Honolulu. November 12, 1917. p. 2 headline. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.