Kingdom of Luba Luba | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1585–1889 | |||||||||

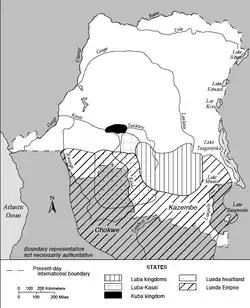

Map of the Lunda Empire and Luba kingdoms in the Congo River Basin around 1850 | |||||||||

| Capital | Mwibele (today in Haut-Lomami) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Kiluba[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| muLopwe | |||||||||

• c. 1780 – 1810 | Ilunga Sungu | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1585 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1889 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• | 1 million | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Luba or Luba Empire (1585–1889) was a pre-colonial Central African state that arose in the marshy grasslands of the Upemba Depression in what is now southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Origins and foundation

Archaeological research shows that the Upemba depression had been occupied continuously since at least the 4th century AD. In the 4th century, the region was occupied by iron-working farmers. Over the centuries, the people of the region learned to use nets, harpoons, make dugout canoes, and clear canals through swamps.[2] They had also learned techniques for drying fish, which were an important source of protein;[2] they began trading the dried fish with the inhabitants of the protein-starved savanna.[3]

By the 6th century, fishing people lived on lakeshores, worked iron, and traded palm oil.[3]

By the 10th century, the people of Upemba had diversified their economy,[3] combining fishing, farming and metal-working. Metal-workers relied on traders to bring them the copper and charcoal that they needed in smelting. Traders exported salt and iron items, and imported glass beads and cowry shells from the distant Indian Ocean.

By the 14th century, the people of the region were organized into various successful farming and trading communities — the gradual process of the communities merging began. Some communities began to merge into larger, more centralized ones; the reason for this is likely because of competition for increasingly limited resources.[2]

The Luba Kingdom was founded by King Kongolo Mwamba around 1585. His nephew and immediate successor, Kalala Ilunga, expanded the empire over the upper left bank territories of the Lualaba River. At its peak, the state had about a million people paying tribute to its king.

Myths

According oral tradition, Kongolo Mwamba founded a capital near Lake Boya. From the east, a hunter known as Ilunga Mbidi Kiluwe arrived. Ilunga married two sisters of Kongolo — Bulanda and Mabele. Hostility grew between Kongolo and Ilunga, to the point where Ilunga left for an unknown location. Bulanda had a son named Kalala Ilunga — Ilunga Mbidi Kiluwe was the father and Kongolo was the uncle. Kalala began to overshadow his uncle. The conflict between the two grew, but turned in Kalala's favour; Kalala eventually seized power and decapitated his uncle. Kalala's reign, the tradition says, initiated an expansionary period for the Kingdom.[4][5] The new Ilunga dynasty, according to tradition, expanded the Kingdom westward past Lake Kisale. The new dynasty also established a more centralized state, where the king ruled closely with governors.[6]

According to the historian Thomas Reefe, the accuracy of the story and the existence of certain figures, like Kolongo, Kalala, and Ilunga, is questionable. Reefe believes that the accounts of Luba's foundation are mythical tales.[7]

Empire

| History of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| See also: Years | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Government

The kingdom of Luba's success was due in large part to its development of a form of a government durable enough to withstand the disruptions of succession disputes and flexible enough to incorporate foreign leaders and governments. The Luba model of governing was so successful that it was adopted by the Lunda Kingdom and spread throughout the region that is today northern Angola, northwestern Zambia, and southern Democratic Republic of Congo.

Law and order were handled by the king, known as the Mulopwe ('sacred king'),[8] with the assistance of a court of nobles known as Bamfumus. The kings reigned over their subjects through clan kings known as Balopwe. The diverse populations of the Luba were linked by the Bambudye, a secret society that kept the memory of the Luba alive and taught throughout the realm.

Kingship

The Mbudye tradition states that all of the rulers of the Luba Empire traced their ancestry to Kalala Ilunga, a mystical hunter credited with toppling Kongolo Mwamba. This figure is also credited with the introduction of advanced iron forging techniques to the Luba peoples. Luba kings became deities upon their deaths, and the villages from which they ruled were transformed into living shrines devoted to their legacies.

The Luba heartland was dotted with these landmarks. Central to Luba regalia for kings and other nobles were mwadi, female incarnations of the ancestral kings. Staffs, headrests, bow stands and royal seats featuring this subject represented the divine status of the ruler and the elegant refinement of his court.

Mbudye

The Luba Kingdom kept official "men of memory" who were part of a group called the Mbudye. They were responsible for maintaining the oral histories associated with kings, their villages and the customs of the land. Parallels to these kinds of officials can be found in neighboring kingdoms such as Kuba and Lunda.

Economy

The local economy led to the development of several small Luba kingdoms. Luba traders linked the Congolese forest to the north with the mineral-rich region in the center of modern Zambia known as the Copperbelt. The trade routes passing through Luba territory were also connected with wider networks extending to both the Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts.

With the formation of the Luba kingdom, the economy was complex and based on a tribute system that redistributed agricultural, hunting and mining resources among nobles. The ruling class held a virtual monopoly on trade items such as salt, copper, and iron ore. This allowed them to continue their dominance in much of Central Africa.

Arts and beliefs

As in the Kuba Kingdom, the Luba Kingdom held the arts in high esteem. A carver held relatively high status, which was displayed by an adze (axe) that he carried over his shoulder. Luba art varied because of the kingdom's vast territory. Some characteristics are common. The important role of woman in the creation myths and political society resulted in the decoration of many presitigious objects with female figures.

Headrests and staffs were of great importance in relation to beliefs about prophetic dreams and ancestor worship. Dreams were believed to communicate messages from the other world. Therefore, it was common to have two priestess figures adorned on a headrest on which one slept. Luba staffs, usually owned by kings, village chiefs or court dignitaries, were also carved with dual or paired female figures. Single figures on art pieces, specifically staffs, represented dead kings whose spirits are carried in a woman's body.

Among the Luba, the name "Nkole" appears at the head of every genealogy. It is an honorific title, with the literal meaning of "the essentially powerful". It was given to the three most distant patriarchs and inserted symbolically in all genealogies.

In Baluba tradition, a kasala is a well-defined form of slogans in free-verse poetry. They are chanted or recited, sometimes with instrumental accompaniment, by men and women who are professional specialists. It dramatizes public events that call for strong emotions, such as courage in battle, collective joy at official functions, and bereavement at funerals. In style and content, the kasala by itself is a diverse genre of proverbs, myths, fables, riddles, tales and historical narratives.

Influence

The prestige attached to the lineage of the sacred kings was enormous, and rulers of small neighboring chiefdoms were eager to associate themselves with Luba culture. In return for tribute in goods and labor, these less powerful rulers were integrated into the royal lineage and adopted the sacred Luba ancestors as their own. Luba courtly traditions, including artistic styles and sculptural forms, were also passed along to client states.

Decline

Ultimately, long-distance trade destroyed the kingdom of Luba. In the 1870s and 1880s, traders from East Africa began searching for slaves and ivory in the savannas of central Africa. The empire was raided for slaves beginning the rapid destruction of the Luba Kingdom. In 1889 it was split in two by a succession dispute, ending the unified state, and later joined the Belgian Congo Free State.

See also

References

- ↑ Augustin MUBIAYI MAMBA, Description des consequences des violations de coutumes luba-kasaï et leurs therapies, Université de Kinshasa - DIPLOME D'ETUDES SUPERIEURES (DES) EN PSYCHOLOGIE, 2014 (in French)

- 1 2 3 Shillington, Kevin (1995). History of Africa. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 140-4. ISBN 0-312-12598-4.

- 1 2 3 Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: The History of a Continent. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-86438-1.

- ↑ Yoder, John C. (2004). "Luba: Origins and Growth". In Shllington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. p. 854. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

- ↑ Nziem, Ndaywel è (1992). "The political system of the Luba and Lunda: its emergence and expansion". In Ogot, Bethwall A. (ed.). General History of Africa, V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press. p. 592. ISBN 978-0520039162.

- ↑ Page, Willie F. (2001). Encyclopedia of African History and Culture: From Conquest to Colonization (1500-1850). Facts on File. p. 157. ISBN 978-0816044726.

- ↑ Petit, Pierre (2004). "Luba: Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries". In Shillington, Kevin (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. p. 855. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

- ↑ "Luba - Art & Life in Africa - The University of Iowa Museum of Art". africa.uima.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

Further reading

- Reefe, Thomas Q. (1981). The Rainbow and the Kings: A History of the Luba Empire to 1891. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520041400.

- Juengst, Daniel African art, women, history: the Luba people of central Africa. Created and produced by Linda Freeman; executive producer, Lorraine E. Hall; written and directed by David Irving; narrated by Dr. Mary Nooter Roberts. Chappaqua, NY: L & S Video, 1998. [Video recording]

- Bantje, Han. Kaonde song and ritual: La musique et son role dans la vie sociale et rituelle Luba. Tervuren: Musee royal de l'Afrique centrale, 1978.

- Bateman, Charles Somerville Latrobe. The first ascent of the Kasai: being some records of service under the Lone Star. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1889.

- Bleakley, Robert. Baluba Mask. New York: St. Martin Press, 1978.

- Bonnke, Reinhard. Church report, Mbuji-Mayi, Zaire. Laguna Hills, CA: Reinhard Bonnke Ministries, 1980-89? [Video recording]

- Brown, H.D. "The Nkumu of the Tumba: ritual chieftainship on the middle Congo". Africa, v. 14 (1944).

- Burton, William Frederick P. God working with them: being eighteen years of Congo evangelistic mission history. London: Victory Press, 1938.

- Burton, William Frederick P. Luba religion and magic in custom and belief. Tervuren: Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, 1961.

- Elisofon, Eliot. Baluba. New York: Frederic A. Praeger, 1958.

- Traditions, changement, histoire: Les "Somba" du Dahomey, Septentrional. Paul Mercier. Paris: Editions Anthro-pos Paris, 1968. xiii + 538 pp.

- Caeneghem, Van R. " Memoire De l’Institut Royal Colonial Belge, Classe des Sciences Morales et politiques." Godsbegrip der Baluba van Kasai. Vol. XXII. Brussels: n.p., 1954. N. pag. Print. 8.

- Bortolot, Alexander Yves. "Kingdoms of the Savanna: The Luba and Lunda Empires." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. Print.