.jpg.webp)

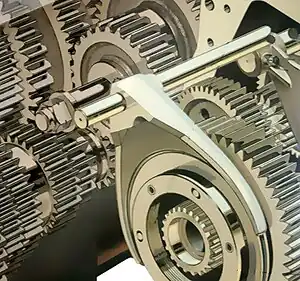

A gear train or gear set is a machine element of a mechanical system formed by mounting two or more gears on a frame such that the teeth of the gears engage.

Gear teeth are designed to ensure the pitch circles of engaging gears roll on each other without slipping, providing a smooth transmission of rotation from one gear to the next.[1] Features of gears and gear trains include:

- The gear ratio of the pitch circles of mating gears defines the speed ratio and the mechanical advantage of the gear set.

- A planetary gear train provides high gear reduction in a compact package.

- It is possible to design gear teeth for gears that are non-circular, yet still transmit torque smoothly.

- The speed ratios of chain and belt drives are computed in the same way as gear ratios. See bicycle gearing.

The transmission of rotation between contacting toothed wheels can be traced back to the Antikythera mechanism of Greece and the south-pointing chariot of China. Illustrations by the Renaissance scientist Georgius Agricola show gear trains with cylindrical teeth. The implementation of the involute tooth yielded a standard gear design that provides a constant speed ratio.

Mechanical advantage

Gear teeth are designed so the number of teeth on a gear is proportional to the radius of its pitch circle, and so the pitch circles of meshing gears roll on each other without slipping. The speed ratio for a pair of meshing gears can be computed from ratio of the radii of the pitch circles and the ratio of the number of teeth on each gear.

The velocity v of the point of contact on the pitch circles is the same on both gears, and is given by:

where input gear A with radius rA and angular velocity ωA meshes with output gear B with radius rB and angular velocity ωB. Therefore,

where NA is the number of teeth on the input gear and NB is the number of teeth on the output gear.

The mechanical advantage of a pair of meshing gears for which the input gear has NA teeth and the output gear has NB teeth is given by

This shows that if the output gear GB has more teeth than the input gear GA, then the gear train amplifies the input torque. And, if the output gear has fewer teeth than the input gear, then the gear train reduces the input torque. If the output gear of a gear train rotates more slowly than the input gear, then the gear train is called a speed reducer. In this case, because the output gear must have more teeth than the input gear, the speed reducer amplifies the input torque.

Analysis using virtual work

For this analysis, consider a gear train that has one degree of freedom, which means the angular rotation of all the gears in the gear train are defined by the angle of the input gear.

The size of the gears and the sequence in which they engage define the ratio of the angular velocity ωA of the input gear to the angular velocity ωB of the output gear, known as the speed ratio, or gear ratio, of the gear train. Let R be the speed ratio, then

The input torque TA acting on the input gear GA is transformed by the gear train into the output torque TB exerted by the output gear GB. Assuming the gears are rigid and there are no losses in the engagement of the gear teeth, then the principle of virtual work can be used to analyze the static equilibrium of the gear train.

Let the angle θ of the input gear be the generalized coordinate of the gear train, then the speed ratio R of the gear train defines the angular velocity of the output gear in terms of the input gear:

The formula for the generalized force obtained from the principle of virtual work with applied torques yields:[2]

The mechanical advantage of the gear train is the ratio of the output torque TB to the input torque TA, and the above equation yields:

The speed ratio of a gear train also defines its mechanical advantage. This shows that if the input gear rotates faster than the output gear, then the gear train amplifies the input torque. And if the input gear rotates slower than the output gear, the gear train reduces the input torque.

Gear trains with two gears

The simplest example of a gear train has two gears. The "input gear" (also known as drive gear) transmits power to the "output gear" (also known as driven gear). The input gear will typically be connected to a power source, such as a motor or engine. In such an example, the output of torque and rotational speed from the output (driven) gear depend on the ratio of the dimensions of the two gears.

Formula

The teeth on gears are designed so the gears can roll on each other smoothly (without slipping or jamming). In order for two gears to roll on each other smoothly, they must be designed so the velocity at the point of contact of the two pitch circles (represented by v) is the same for each gear.

Mathematically, if the input gear GA has the radius rA and angular velocity , and meshes with output gear GB of radius rB and angular velocity , then:

The number of teeth on a gear is proportional to the radius of its pitch circle, which means the ratios of the gears' angular velocities, radii, and number of teeth are equal. Where NA is the number of teeth on the input gear and NB is the number of teeth on the output gear, the following equation is formed:

This shows that a simple gear train with two gears has the gear ratio R given by:

This equation shows that if the number of teeth on the output gear GB is larger than the number of teeth on the input gear GA, then the input gear GA must rotate faster than the output gear GB.

Double reduction gear

A double reduction gear set comprises two pairs of gears, each individually single reductions, in series. In the diagram, the red and blue gears give the first stage of reduction and the orange and green gears give the second stage of reduction. The total reduction is the product of the first stage of reduction and the second stage of reduction.

It is essential to have two coupled gears, of different sizes, on the intermediate layshaft. If a single intermediate gear was used, the overall ratio would be simply that between the first and final gears, the intermediate gear would only act as an idler gear: it would reverse the direction of rotation, but not change the ratio.

Hunting and non-hunting gear sets

A hunting gear set is a set of gears where the gear teeth counts are relatively prime on each gear in an interfacing pair. Since the number of teeth on each gear have no common factors, then any tooth on one of the gears will come into contact with every tooth on the other gear before encountering the same tooth again. This results in less wear and longer life of the mechanical parts. A non-hunting gear set is one where the teeth counts are insufficiently prime. In this case, some particular gear teeth will come into contact with particular opposing gear teeth more times than others, resulting in more wear on some teeth than others.[3][4]

Speed ratio

Gear teeth are distributed along the circumference of the pitch circle so the thickness t of each tooth and the space between neighboring teeth are the same. The pitch p of the gear, which is the distance between equivalent points on neighboring teeth along the pitch circle, is equal to twice the thickness of a tooth,

The pitch of a gear GA can be computed from the number of teeth NA and the radius rA of its pitch circle

In order to mesh smoothly two gears GA and GB must have the same sized teeth and therefore they must have the same pitch p, which means

This equation shows that the ratio of the circumference, the diameters and the radii of two meshing gears is equal to the ratio of their number of teeth,

The speed ratio of two gears rolling without slipping on their pitch circles is given by,

therefore

In other words, the gear ratio, or speed ratio, is inversely proportional to the radius of the pitch circle and the number of teeth of the input gear.

Torque ratio

A gear train can be analyzed using the principle of virtual work to show that its torque ratio, which is the ratio of its output torque to its input torque, is equal to the gear ratio, or speed ratio, of the gear train.

This means the input torque ΤA applied to the input gear GA and the output torque ΤB on the output gear GB are related by the ratio

where R is the gear ratio of the gear train.

The torque ratio of a gear train is also known as its mechanical advantage

Idler gears

In a sequence of gears chained together, the ratio depends only on the number of teeth on the first and last gear. The intermediate gears, regardless of their size, do not alter the overall gear ratio of the chain. However, the addition of each intermediate gear reverses the direction of rotation of the final gear.

An intermediate gear which does not drive a shaft to perform any work is called an idler gear. Sometimes, a single idler gear is used to reverse the direction, in which case it may be referred to as a reverse idler. For instance, the typical automobile manual transmission engages reverse gear by means of inserting a reverse idler between two gears.

Idler gears can also transmit rotation among distant shafts in situations where it would be impractical to simply make the distant gears larger to bring them together. Not only do larger gears occupy more space, the mass and rotational inertia (moment of inertia) of a gear is proportional to the square of its radius. Instead of idler gears, a toothed belt or chain can be used to transmit torque over distance.

Formula

If a simple gear train has three gears, such that the input gear GA meshes with an intermediate gear GI which in turn meshes with the output gear GB, then the pitch circle of the intermediate gear rolls without slipping on both the pitch circles of the input and output gears. This yields the two relations

The speed ratio of this gear train is obtained by multiplying these two equations to obtain

Notice that this gear ratio is exactly the same as for the case when the gears GA and GB engage directly. The intermediate gear provides spacing but does not affect the gear ratio. For this reason it is called an idler gear. The same gear ratio is obtained for a sequence of idler gears and hence an idler gear is used to provide the same direction to rotate the driver and driven gear. If the driver gear moves in the clockwise direction, then the driven gear also moves in the clockwise direction with the help of the idler gear.

Example

In the photo, assuming the smallest gear is connected to the motor, it is called the drive gear or input gear. The somewhat larger gear in the middle is called an idler gear. It is not connected directly to either the motor or the output shaft and only transmits power between the input and output gears. There is a third gear in the upper-right corner of the photo. Assuming that gear is connected to the machine's output shaft, it is the output or driven gear.

The input gear in this gear train has 13 teeth and the idler gear has 21 teeth. Considering only these gears, the gear ratio between the idler and the input gear can be calculated as if the idler gear was the output gear. Therefore, the gear ratio is driven/drive = 21/13 ≈1.62 or 1.62:1.

At this ratio, it means the drive gear must make 1.62 revolutions to turn the driven gear once. It also means that for every one revolution of the driver, the driven gear has made 1/1.62, or 0.62, revolutions. Essentially, the larger gear turns slower.

The third gear in the picture has 42 teeth. The gear ratio between the idler and third gear is thus 42/21, or 2:1, and hence the final gear ratio is 1.62x2≈3.23. For every 3.23 revolutions of the smallest gear, the largest gear turns one revolution, or for every one revolution of the smallest gear, the largest gear turns 0.31 (1/3.23) revolution, a total reduction of about 1:3.23 (Gear Reduction Ratio (GRR) = 1/Gear Ratio (GR)).

Since the idler gear contacts directly both the smaller and the larger gear, it can be removed from the calculation, also giving a ratio of 42/13≈3.23. The idler gear serves to make both the drive gear and the driven gear rotate in the same direction, but confers no mechanical advantage.

Belt drives

Belts can have teeth in them also and be coupled to gear-like pulleys. Special gears called sprockets can be coupled together with chains, as on bicycles and some motorcycles. Again, exact accounting of teeth and revolutions can be applied with these machines.

(The small gear in the lower left is on the balance shaft.)

For example, a belt with teeth, called the timing belt, is used in some internal combustion engines to synchronize the movement of the camshaft with that of the crankshaft, so that the valves open and close at the top of each cylinder at exactly the right time relative to the movement of each piston. A chain, called a timing chain, is used on some automobiles for this purpose, while in others, the camshaft and crankshaft are coupled directly together through meshed gears. Regardless of which form of drive is employed, the crankshaft-to-camshaft gear ratio is always 2:1 on four-stroke engines, which means that for every two revolutions of the crankshaft the camshaft will rotate once.

Automotive applications

Automobile drivetrains generally have two or more major areas where gear sets are used. For internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, gearing is typically employed in the transmission, which contains a number of different sets of gears that can be changed to allow a wide range of vehicle speeds to accommodate the low torque of an ICE engine at both low and high speeds. The second common gear set in almost all motor vehicles is the differential, which contains the final drive to and often provides additional speed reduction at the wheels. Moreover, the differential contains gearing that splits torque equally between the two wheels while permitting them to have different speeds when traveling in a curved path.

The transmission and final drive might be separate and connected by a driveshaft, or they might be combined into one unit called a transaxle. The gear ratios in transmission and final drive are important because different gear ratios will change the characteristics of a vehicle's performance.

Example

A 2004 Chevrolet Corvette C5 Z06 with a six-speed manual transmission has the following gear ratios in the transmission:

| Gear | Ratio |

|---|---|

| 1st gear | 2.97:1 |

| 2nd gear | 2.07:1 |

| 3rd gear | 1.43:1 |

| 4th gear | 1.00:1 |

| 5th gear | 0.84:1 |

| 6th gear | 0.56:1 |

| reverse | −3.38:1 |

In 1st gear, the engine makes 2.97 revolutions for every revolution of the transmission's output. In 4th gear, the gear ratio of 1:1 means that the engine and the transmission's output rotate at the same speed, referred to as the "direct drive" ratio. 5th and 6th gears are known as overdrive gears, in which the output of the transmission is revolving faster than the engine's output.

The Corvette above has an axle ratio of 3.42:1, meaning that for every 3.42 revolutions of the transmission's output, the wheels make one revolution. The differential ratio multiplies with the transmission ratio, so in 1st gear, the engine makes 10.16 revolutions for every revolution of the wheels.

The car's tires can almost be thought of as a third type of gearing. This car is equipped with 295/35-18 tires, which have a circumference of 82.1 inches. This means that for every complete revolution of the wheel, the car travels 82.1 inches (209 cm). If the Corvette had larger tires, it would travel farther with each revolution of the wheel, which would be like a higher gear. If the car had smaller tires, it would be like a lower gear.

With the gear ratios of the transmission and differential and the size of the tires, it becomes possible to calculate the speed of the car for a particular gear at a particular engine RPM.

For example, it is possible to determine the distance the car will travel for one revolution of the engine by dividing the circumference of the tire by the combined gear ratio of the transmission and differential.

It is also possible to determine a car's speed from the engine speed by multiplying the circumference of the tire by the engine speed and dividing by the combined gear ratio.

Note that the answer is in inches per minute, which can be converted to mph by dividing by 1056.[5]

| Gear | Distance per engine revolution | Speed per 1000 RPM |

|---|---|---|

| 1st gear | 8.1 in (210 mm) | 7.7 mph (12.4 km/h) |

| 2nd gear | 11.6 in (290 mm) | 11.0 mph (17.7 km/h) |

| 3rd gear | 16.8 in (430 mm) | 15.9 mph (25.6 km/h) |

| 4th gear | 24.0 in (610 mm) | 22.7 mph (36.5 km/h) |

| 5th gear | 28.6 in (730 mm) | 27.1 mph (43.6 km/h) |

| 6th gear | 42.9 in (1,090 mm) | 40.6 mph (65.3 km/h) |

Wide-ratio vs. close-ratio transmission

A close-ratio transmission is a transmission in which there is a relatively little difference between the gear ratios of the gears. For example, a transmission with an engine shaft to drive shaft ratio of 4:1 in first gear and 2:1 in second gear would be considered wide-ratio when compared to another transmission with a ratio of 4:1 in first and 3:1 in second. This is because the close-ratio transmission has less of a progression between gears. For the wide-ratio transmission, the first gear ratio is 4:1 or 4, and in second gear it is 2:1 or 2, so the progression is equal to 4/2 = 2 (or 200%). For the close-ratio transmission, first gear has a 4:1 ratio or 4, and second gear has a ratio of 3:1 or 3, so the progression between gears is 4/3, or 133%. Since 133% is less than 200%, the transmission with the smaller progression between gears is considered close-ratio. However, the difference between a close-ratio and wide-ratio transmission is subjective and relative.[6]

Close-ratio transmissions are generally offered in sports cars, sport bikes, and especially in race vehicles, where the engine is tuned for maximum power in a narrow range of operating speeds, and the driver or rider can be expected to shift often to keep the engine in its power band.

Factory 4-speed or 5-speed transmission ratios generally have a greater difference between gear ratios and tend to be effective for ordinary driving and moderate performance use. Wider gaps between ratios allow a higher 1st gear ratio for better manners in traffic, but cause engine speed to decrease more when shifting. Narrowing the gaps will increase acceleration at speed, and potentially improve top speed under certain conditions, but acceleration from a stopped position and operation in daily driving will suffer.

Range is the torque multiplication difference between 1st and 4th gears; wider-ratio gear-sets have more, typically between 2.8 and 3.2. This is the single most important determinant of low-speed acceleration from stopped.

Progression is the reduction or decay in the percentage drop in engine speed in the next gear, for example after shifting from 1st to 2nd gear. Most transmissions have some degree of progression in that the RPM drop on the 1-2 shift is larger than the RPM drop on the 2-3 shift, which is in turn larger than the RPM drop on the 3-4 shift. The progression may not be linear (continuously reduced) or done in proportionate stages for various reasons, including a special need for a gear to reach a specific speed or RPM for passing, racing and so on, or simply economic necessity that the parts were available.

Range and progression are not mutually exclusive, but each limits the number of options for the other. A wide range, which gives a strong torque multiplication in 1st gear for excellent manners in low-speed traffic, especially with a smaller motor, heavy vehicle, or numerically low axle ratio such as 2.50, means the progression percentages must be high. The amount of engine speed, and therefore power, lost on each up-shift is greater than would be the case in a transmission with less range, but less power in 1st gear. A numerically low 1st gear, such as 2:1, reduces available torque in 1st gear, but allows more choices of progression.

There is no optimal choice of transmission gear ratios or a final drive ratio for best performance at all speeds, as gear ratios are compromises, and not necessarily better than the original ratios for certain purposes.

See also

- Machine (mechanical)

- Mechanism (engineering)

- Powertrain

- Wheel train (horology)

- Outline of machines

- Epicyclic gearing - related to turboprop reduction gear boxes

- Continuously variable transmission (CVT)

- Virtual work

References

- ↑ Uicker, J. J.; G. R. Pennock; J. E. Shigley (2003). Theory of Machines and Mechanisms. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Paul, B. (1979). Kinematics and Dynamics of Planar Machinery. Prentice Hall.

- ↑ "Why choose ring and pinion gears". amtechinternational.com. 5 December 2023.

- ↑ "Hunting Vs Non Hunting Gears (What You Should Know!)". goenthusiast.com. 5 December 2023.

- ↑ "Google: convert in/min to mph". Retrieved 2018-11-24.

Formula: divide the speed value by 1056

- ↑ Cangialosi, Paul (2001). "TechZone Article: Wide and Close Gear Ratios". 5speeds.com. Medatronics. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.