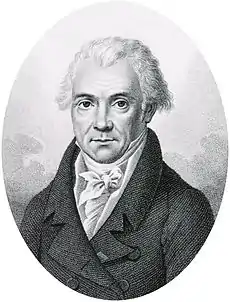

Louis Nicolas Vauquelin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16 May 1763 Saint-André-d'Hébertot, Normandy, France |

| Died | 14 November 1829 (aged 66) Saint-André-d'Hébertot, Normandy, France |

| Known for | Beryllium Chromium Asparagine |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Chemistry |

| Doctoral advisor | Antoine Francois de Fourcroy |

| Doctoral students | Friedrich Stromeyer Louis Thénard |

Louis Nicolas Vauquelin FRS(For) HFRSE (16 May 1763 – 14 November 1829) was a French pharmacist and chemist. He was the discoverer of both chromium and beryllium.

Early life

Vauquelin was born at Saint-André-d'Hébertot in Normandy, France, the son of Nicolas Vauquelin, an estate manager, and his wife, Catherine Le Charterier.[1]

His first acquaintance with chemistry was gained as laboratory assistant to an apothecary in Rouen (1777–1779), and after various vicissitudes he obtained an introduction to A. F. Fourcroy, in whose laboratory he was an assistant from 1783 to 1791.

Moving to Paris, he became a laboratory assistant at the Jardin du Roi and was befriended by a professor of chemistry. In 1791 he was made a member of the Academy of Sciences and from that time he helped to edit the journal Annales de Chimie (Chemical annals), although he left the country for a while during the height of the French Revolution. In 1798 Vauquelin discovered beryllium oxide by extracting it from an emerald (a beryl variety); Klaproth isolated the element from the oxide.[2]

Contributions to chemistry

At first his work appeared as that of his master and patron Fourcroy, then in their joint names; in 1790 he began to publish on his own, and between that year and 1833 his name is associated with 376 papers. Most of these were simple records of patient and laborious analytical operations, and it is perhaps surprising that among all the substances he analysed he detected only two new elements, beryllium in 1798 in beryl and chromium in 1797 in a red lead ore from Siberia. He also managed to get liquid ammonia at atmospheric pressure. Later with Fourcroy, he identified a metal in a platinum residue they called ‘ptène’, This name ‘ptene’ or ‘ptène’ was reported as an early synonym for osmium.[3]

Either together or successively he held the offices of inspector of mines, professor at the School of Mines and at the Polytechnic School, assayer of gold and silver articles, professor of chemistry in the College de France and at the Jardin des Plantes, member of the Council of Industry and Commerce, commissioner on the pharmacy laws, and finally professor of chemistry to the Medical Faculty, to which he succeeded on Fourcroy's death in 1809. His lectures, which were supplemented with practical laboratory teaching, were attended by many chemists who subsequently attained distinction.

A lesser-known contribution and finding of his included the study of hens fed a known amount of mineral. "Having calculated all the lime in oats fed to a hen, found still more in the shells of its eggs. Therefore, there is a creation of matter. In what way, no one knows."

Final achievements, days and legacy

From 1809 he was professor at the University of Paris. He was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1811[4] and a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1816. He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1828. In 1806, working with asparagus, he and Pierre Jean Robiquet (future discoverer of the famous red dye alizarin, then a young chemist and his assistant) isolated the amino acid asparagine, the first one to be discovered. He also discovered pectin and malic acid in apples, and isolated camphoric acid and quinic acid.

His death occurred while he was on a visit to his birthplace.

Among his best known works is "Manuel de l'essayeur" (Manual of the assayer).

The plant genus Vauquelinia is named in his honour, as is the Vauquelin, a white of egg foam associated with molecular gastronomy, and the mineral vauquelinite, discovered at the same mine as the crocoite from which Vauquelin isolated chromium.

References

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2019-01-04.

- ↑ Weeks, Mary Elvira; Leichester, Henry M. (1968). Discovery of the Elements. Easton, PA: Journal of Chemical Education. LCCCN 68-15217.

- ↑ Haubrichs, Rolf; Zaffalon, Pierre-Leonard (2017). "Osmium vs. 'Ptène': The Naming of the Densest Metal". Johnson Matthey Technology Review. 61 (3): 190–196. doi:10.1595/205651317x695631.

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- "Louis Nicolas Vauquelin (1763–1829)". Archived from the original on 18 November 2005. Retrieved 3 September 2005.

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin". Louis-Nicolas Vauquelin. Retrieved 3 September 2005.

- "Vauquelin, Louis Nicolas". Archived from the original on 28 November 2005. Retrieved 4 September 2005.

- Kyle, R A; Shampo, M A (1989). "Nicolas-Louis Vauquelin—discoverer of chromium". Mayo Clin. Proc. Vol. 64, no. 6 (published Jun 1989). p. 643. PMID 2664360.

- WILLIAMS-ASHMAN, H G (1965). "NICOLAS LOUIS VAUQUELIN (1763–1829)". Investigative Urology. Vol. 2 (published May 1965). pp. 605–13. PMID 14283607.

- Louis Nicolas Vauquelin at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vauquelin, Louis Nicolas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.