The Earl of Ypres | |

|---|---|

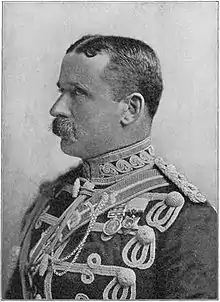

Photograph of John French, 1st Earl of Ypres, Commander-in-Chief | |

| Birth name | John Denton Pinkstone French |

| Born | 28 September 1852 Ripple, Kent, England |

| Died | 22 May 1925 (aged 72) Deal, Kent, England |

| Buried | Ripple, Kent |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1866–1921 |

| Rank | Field Marshal |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | |

| Relations | Charlotte Despard (sister) |

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, PC (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925), known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent to an Anglo-Irish family, he saw brief service as a midshipman in the Royal Navy, before becoming a cavalry officer. He achieved rapid promotion and distinguished himself on the Gordon Relief Expedition. French had a considerable reputation as a womaniser throughout his life, and his career nearly ended when he was cited in the divorce of a brother officer while in India in the early 1890s.

French became a national hero during the Second Boer War. During the Edwardian period he commanded I Corps at Aldershot, then served as Inspector-General of the Army, before becoming Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS, the professional head of the British Army) in 1912. During this time he helped to prepare the British Army for a possible European war, and was also one of those who insisted, in the so-called "cavalry controversy", that cavalry still be trained to charge with sabre and lance. During the Curragh incident he had to resign as CIGS after promising Hubert Gough in writing that the Army would not be used to coerce Ulster Protestants into a Home Rule Ireland.

French's most important role was as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) for the first year and a half of the First World War. He had an immediate personality clash with the French General Charles Lanrezac. After the British suffered heavy casualties at the battles of Mons and Le Cateau (where Smith-Dorrien made a stand contrary to French's wishes), French wanted to withdraw the BEF from the Allied line to refit and only agreed to take part in the First Battle of the Marne after a private meeting with the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, against whom he bore a grudge thereafter. In May 1915 he leaked information about shell shortages to the press in the hope of engineering Kitchener's removal. By summer 1915 French's command was being increasingly criticised in London by Kitchener and other members of the government, and by Haig, Robertson and other senior generals in France. After the Battle of Loos, at which French's slow release of XI Corps from reserve was blamed for the failure to achieve a decisive breakthrough on the first day, H. H. Asquith, the British Prime Minister, demanded his resignation. He was replaced by Haig, who was formerly French's trusted subordinate and who had saved him from bankruptcy by lending him a large sum of money in 1899.

French was then appointed Commander-in-Chief, Home Forces for 1916–1918. This period saw the country running increasingly short of manpower for the Army. While the Third Battle of Ypres was in progress, French, as part of Lloyd George's manoeuvres to reduce the power of Haig and Robertson, submitted a paper which was critical of Haig's command record and which recommended that there be no further major offensives until the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) was present in strength. He then became Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1918, a position he held throughout much of the Irish War of Independence (1919–1922), in which his own sister was involved on the republican side. During this time he published 1914, an inaccurate and much criticised volume of memoirs.

Early life and career

Family

French's family was related to the French/De Freyne family which had gone to present-day County Wexford in the fourteenth century and had substantial estates at Frenchpark, County Roscommon. French always regarded himself as "Irish", although his branch of the family had lived in England since the eighteenth century.[1][2][3]

His father was Commander John Tracey William French, RN, who had fought at Navarino and under Napier in support of Dom Pedro in the Portuguese Civil War.[3] His mother was Margaret Eccles, from Glasgow, who after suffering a breakdown following her husband's death was eventually institutionalised.[4] She died in 1867 leaving French to be brought up by his sisters.[5][6] He was educated at a Harrow preparatory school and Eastman's Royal Naval Academy at Portsmouth[6] before joining the Royal Navy in 1866.[7]

Royal Navy

He joined the Royal Navy because it gave him a chance to leave home four or five years earlier than the Army. From August 1866 he trained on board the three-decker battleship HMS Britannia at Dartmouth. He obtained only an "average" certificate which required him to do a further six months of training on board the frigate HMS Bristol at Sheerness from January 1868 before qualifying as a midshipman.[8]

In 1869 he served as a midshipman on HMS Warrior commanded by Captain Boys, an old friend of French's father. She patrolled in the English Channel and off Spain and Portugal. While in Lisbon French was able to hire horses and ride over Wellington's old battlefields. During his service he also witnessed the accidental sinking of HMS Captain. He resigned from the Royal Navy in November 1870[1][8] as he was discovered to be acrophobic[9] and to suffer from seasickness.[10]

Early army career

French joined the Suffolk Artillery Militia in November 1870[11] where he was expected to put in about two months a year with the regiment. He initially failed his exams (mathematics and foreign languages) for a regular commission and had to hire a new tutor losing the fees he had paid in advance to the previous one.[12]

He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars on 28 February 1874,[11] but there is no evidence that he ever served with them.[12] He transferred to the 19th Hussars on 11 March 1874[13] possibly as it was less expensive—following the sale of the family home at Ripple Valley French's private income of £1,000 per annum was enough to cover the £500–£600 required by his new regiment.[12] He was posted to Aldershot Command.[14] He became an expert hunter and steeplechaser, permanently damaging the little finger of his right hand in a fall.[15]

The 19th Hussars were posted to Ireland in June 1876. In September 1877 French was one of two lieutenants who persuaded 70 drunk and mutinous troopers, who had armed themselves with sticks and threatened "murder" if infantry pickets were sent after them, to return to barracks (the ringleaders were subsequently imprisoned).[16] In the autumn of 1880 the 19th were deployed to Ballinrobe and Lough Mask to protect labourers ricking hay at the height of the Captain Boycott disturbances. An Irishman hamstrung French's horse with a sickle while he was sitting on it.[17]

He became adjutant of his regiment on 1 June 1880.[18] At that time the 19th Hussars had only one major but as three different men held that rank in three years (1877–1880) the resulting turnover of officers brought French his promotion to captain[17] on 16 October 1880.[19]

He became adjutant of the Northumberland Hussars on 1 April 1881.[20] While in Northumberland he missed out on active service: the 19th Hussars took part in the occupation of Egypt and Battle of Tel el-Kebir (13 September 1882) but French's applications to rejoin his regiment were rejected by the War Office.[21] An increase in the number of majors in the 19th Hussars brought French promotion to that rank on 3 April 1883.[22][23] These promotions (captain at the age of 28, major at 30) were relatively rapid.[24]

Sudan

French was initially expected to rejoin his regiment when they returned to Ireland, but the emergence of the Mahdi in the Sudan required them to remain in the theatre, fighting Mahdist forces in the eastern Sudan near Suakin. French eventually rejoined the regiment when they returned to Cairo in October 1884.[1][25]

French took part in the Sudan expedition to relieve Major-General Charles Gordon in 1884.[7] He was second-in-command to his friend Lieutenant Colonel Percy Barrow, with the cavalry which accompanied Brigadier-General Sir Herbert Stewart as he took the short route across 176 miles of desert (the other British force under Major-General William Earle marched the long way along the bend of the Nile). Most of the cavalry work was in reconnaissance and warding off Dervish raids, although they did—at a walk—pursue the retreating enemy after the Battle of Abu Klea in January 1885. By the time they reached the Nile the horses had not been watered for between 56 and 72 hours.[26] During the retreat back across the desert via Jakdul (the expedition had reached Khartoum too late to save Gordon) Major French led a rearguard of thirteen men, again warding off Dervish attacks and impressing Redvers Buller and Sir Garnet Wolseley.[27]

He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on 7 February 1885.[28][29] Once again, this was an unusually early promotion, and he was appointed second-in-command of the 19th Hussars. His experience of handling cavalry with scarce water would stand him in good stead in South Africa. In January 1886 he briefly acted as Commanding Officer when Colonel Barrow died,[30] but French was considered too young for the position, and Colonel Boyce Combe was transferred in from the 10th Hussars.[31]

From June 1886 to April 1888 French was stationed at Norwich with the regiment.[32] He became Commanding Officer of the 19th Hussars—still aged only 36—on 27 September 1888.[33][34] He impressed Evelyn Wood by his initiative in organising his regiment into squadrons commanded by majors.[35][36]

India and divorce scandal

He was promoted brevet colonel (7 February 1889), and was posted to India in September 1891.[39] There, at cavalry camp during an exercise in November 1891, he first met Captain Douglas Haig, with whose career his own was to be entwined for the next 25 years.[24] French became Assistant Adjutant-General of Cavalry in 1893.[7]

In India serving initially at Secunderabad and Bangalore, French worked as a staff officer under Sir George Luck,[40] a noted trainer of cavalry, albeit with perhaps an excessive emphasis on parade-ground drill.[41] French commanded a brigade of Indian Cavalry on manoeuvres near Lahore in January 1893. He seems not to have acquired the deep affection for India common in officers who served there.[38]

French's wife did not accompany him to India (they seem to have lived apart for a while after his return from Egypt).[42] When commanding the 19th Hussars in India, French was cited for adultery with the wife of a brother officer during his leave in the Indian hills; he was lucky this did not terminate his career.[43] There were also unsubstantiated rumours that French had had affairs with the daughter of an Anglo-Indian railway official and also, earlier in his career, with his commanding officer's wife.[44] A later tale, that he had once been the lover of the Irish nationalist Maud Gonne, appeared in Mary Colum's Life and the Dream (1947), although his biographer comments that it "lacks firm evidence".[45]

He was on half-pay in 1893–1895, possibly as a result of the Indian divorce scandal, and reduced to bicycling with his sons as he could not afford to keep horses.[43] According to his son Gerald he would hop alongside the bicycle as he never mastered the art of mounting it.[46]

Career saved twice

Two years on half pay would normally have meant compulsory retirement but in autumn 1894 he temporarily commanded a cavalry brigade under Lieutenant-General Sir James Keith-Fraser on the manoeuvres in the Vale of the White Horse in Berkshire. French commented that the role of modern cavalry was not to "cut and hack and thrust" but rather to herd the enemy within range of friendly artillery. His handling of the brigade was seen as one of the few successful parts of the manoeuvres, and Luck replaced Keith-Fraser as Inspector General. The introduction of cavalry brigades was also an innovation, supported by French.[47]

Buller got him a job as Assistant Adjutant-General at Army Headquarters on 24 August 1895,[48] writing a new cavalry training manual (in practice extensively assisted by Captain Douglas Haig).[39] However, Buller had been Adjutant-General since 1890, and French's appointment coincided with Luck's arrival as Inspector-General, suggesting that Luck's influence was more important.[44] Ian Beckett agrees, adding that French was also a protege of the influential General Evelyn Wood.[24]

French went on to be Commander of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade at Canterbury on 1 May 1897[49] and Commander of the 1st Cavalry Brigade at Aldershot Command on 12 January 1899.[50]

Haig, recently returned from the Sudan War, was French's brigade-major at Aldershot.[24] French was promoted to temporary major-general early in 1899. There were some accusations that these promotions, for a man whose career had so recently nearly ended, relied too much on powerful patrons.[51] Early in 1899, at his own request, French borrowed £2,500, in a formal contract with interest, from Haig. He was within 24 hours of bankruptcy—which would have required him to resign his commission—after unwise investments in South African mining shares (Transvaal Golds), which crashed in value as war loomed. Richard Holmes believed the loan was never repaid,[52] but Haig's biographer Walter Reid believes that the loan was probably repaid in 1909.[53]

Boer War

Early war

Arrival

French embarked from Southampton for the Second Boer War on 23 September 1899, inviting Haig to share his cabin.[54] War had not yet officially been declared when French put to sea. British troops were being sent in the hope of intimidating President Paul Kruger of the Transvaal into granting equal voting rights to the Uitlanders—non-Boer settlers—which would break the Boer stronghold on political power. It had the opposite effect, as the Boers issued their own ultimatum on 9 October, while the British troops were still at sea, in the hope of provoking an anti-British rising by the Boers of the British-ruled Cape Colony.[55] He was appointed both a major-general on the staff and a local major-general.[56]

French arrived at Cape Town on 11 October. He had expected to command a cavalry brigade under Lieutenant-General George White in Natal, White also had the equivalent of a division of infantry but Colonel Brocklehurst was appointed to this command, while French and Haig were ordered to proceed to Natal "for the present" after receiving a cable from the Nord Office,[57] which they guessed correctly meant that they were to take charge of the Cavalry Division when Buller's Army Corps arrived. After steaming to Durban French and Haig arrived in Ladysmith at 5:40am on 20 October, just as hostilities were beginning.[58]

Elandslaagte

On the morning of his arrival, French was ordered to investigate reports that the Boers had taken Elandslaagte, north-east of Ladysmith, cutting communications with Major-General Penn Symons's force at Dundee. Taking with him the 5th Lancers, six squadrons of Natal Carbineers and Natal Mounted Rifles, a battery of field artillery and a brigade of infantry under Colonel Ian Hamilton, he made contact with the Boers at 13:00 that day. White was initially cautious but on 21 October, having learned of Symons' victory at Talana the previous day, he permitted French to attack. Concerned at French's lack of experience at commanding infantry, White initially proposed that his chief of staff Maj-Gen Archibald Hunter take command, but Hunter advised that French should be left in command. White himself came merely to observe, satisfied that the infantry were in Hamilton's capable hands.[59] French enjoyed numerical superiority of around 3:1.[60][61]

Elandslaagte saw British cavalry charge with the lance, cutting down fleeing Boers amid gory scenes described by one British officer as "most excellent pig-sticking". This was portrayed as proving the continued relevance of old-fashioned cavalry charges, but in fact owed much to special circumstances: the success of Hamilton's preceding infantry attack, and the fact that the charge was carried out at dusk.[62] French celebrated the anniversary of this small battle for the rest of his life. At the time it was seized on by the press in Britain.[63]

That night White ordered all British forces to fall back on Ladysmith, where it was soon clear that they were about to be besieged by the combined Transvaal and Orange Free State forces. French spent much of 26 and 27 October patrolling around the advancing Boer forces. On 30 October his cavalry fought dismounted at Lombard's Kop north-east of Ladysmith; this was the right flank of three unsuccessful actions—the others being Nicholson's Nek and an infantry action at Long Hill in the centre which ended in near-rout—fought by White's troops on "Mournful Monday".[64]

Although French pointed out that cavalry were unlikely to be of much use in a besieged town, White refused him permission to break out. On 2 November, after he had spent the morning on a raid on a Boer laager, French received orders to leave Ladysmith. French and Haig escaped under fire on the last train out as the Boer siege began; Boers tore up the track minutes after the train passed. Steaming from Durban on 3 November, he arrived at Cape Town on 8 November, meeting with Buller, whose Army Corps was then arriving.[39][65]

Colesberg operations

French was initially ordered to assemble the Cavalry Division at Maitland, near Cape Town. Now a local lieutenant-general like Buller's other four division commanders, he was then ordered to take command of forces covering the Colesberg area, filling in the gap between Methuen's division (operating at Orange River Station, with a view to relieving Kimberley and Mafeking) and Gatacre's Division at Stormberg. On 18 November he went up to De Aar, nearer the front, to confer with Maj-Gen Wauchope, in charge of the lines of communication.[66]

French arrived at Naawpoort on the afternoon of 20 November, and personally led a reconnaissance the following morning. The Boer force of General Schoeman[lower-alpha 1] had been reinforced by local Boers, and French, not strong enough to attack Arundel directly, conducted an active defence. At one stage, in late November and until 14 December, he was also required to extend his forces east to Rosmead to protect the railway to Port Elizabeth on the coast. A Boer penetration here would have cut off Cape Colony from Natal. French was proud of having achieved "moral ascendancy" (keeping the initiative, in modern parlance) over the Boers despite his force of 2,000 men being outnumbered by two to one. French's subordinate Colonel T. C. Porter won a small action near Vaal Kop on 13 December, but the Boers captured that place on 16 December, causing French to go forward and take personal command. Around this time he offered to cancel his plans to advance on Colesberg and lend his cavalry to Methuen, who had been defeated at Magersfontein, but this was rejected as there was insufficient water even for Methuen's own horses in the Modder River sector.[67]

Between Field Marshal Frederick Roberts' appointment as Commander-in-Chief on 17 December 1899 (following the defeats of Black Week) and arrival at Cape Town on 10 January, French was the only senior British commander to conduct active operations. Although Schoeman's force had grown further in size, he had lost the confidence of his subordinates and, after a Boer council of war, fell back on a strong position surrounded by hills at Colesberg (29 December) just as French had been preparing to outflank him. French instead (1 January 1900) pinned down the Boer forces and turned their right flank (the British left). The fighting went on until 25 January, with French several times attempting to turn the Boer flanks but pulling back as his forces ran into resistance.[68]

French did not succeed in capturing Colesberg, but he had prevented a Boer invasion of the Cape and tied down Boer forces which might have been used elsewhere. Leo Amery's Times History, highly critical of British generalship during this period, later wrote of his "almost unbroken series of successes", showing grasp of tactics and skill at throwing every available man into battle at the exact right moment. Cavalry—often fighting dismounted—never made up more than half of his force, and were usually outnumbered three-to-one by Boer cavalry.[69] There were some accusations that French was a glory-hunter.[70]

Under Roberts

Cavalry Division

French was one of the few senior officers to be retained by Roberts.[39] Roberts summoned French to Cape Town on 29 January to inquire about expenditure of horses and ammunition around Colesberg. The plan for the Relief of Kimberley was, as the Official History later put it, "only incidentally disclosed" in the meeting. French came away with the impression that he had "only with difficulty persuaded (Roberts and Kitchener) on 29 January to send the Cavalry Division and himself in command of it". Given that he received written orders on 30 January, this is unlikely to have been the case, but French's insecurity was increased by this turn of events—not only did he belong to the wrong faction in the Army—the followers of Wolseley and Buller—now in eclipse, but he had up until now been denied command both of the cavalry brigade in Natal and the Cavalry Division (instead being given ad hoc forces to command in both cases).[71]

French was affectionate about "dear old Bobs" but sometimes took a dim view of his military abilities. He correctly predicted that the centralisation of transport would lead to a collapse in supply arrangements.[72] French disliked William Nicholson, under whose control Roberts had centralised all transport, and retained autonomy for Cavalry Division transport.[39]

Unlike Roberts, French and Haig believed that cavalry should still be trained to charge with cold steel as well as to fight dismounted with firearms. They appreciated the value of good colonial troops and trained Mounted Infantry, but had already (according to Haig's letter to his sister 8 December 1899) insisted that the New Zealand Mounted Rifles fix bayonets to their carbines to use as lances, and were sceptical about the Colonial "Skallywag" units which Roberts was raising. Roberts also appointed the Earl of Erroll as Assistant Adjutant-General (AAG) of the Cavalry Division, with Haig, to whom Buller had promised the job, as his deputy—French did his best to bypass Erroll and work through Haig.[73] On 31 January French returned to the Colesberg front to break up his old command, leaving Maj-Gen R. A. P. Clemens to cover the Colesberg area with a mixed force.[74]

March to relieve Kimberley

Kitchener ordered French (10 February) "The cavalry must relieve Kimberley at all costs ... If it fails neither I nor the Field Marshal can tell what the effect on the Empire may be".[75] French promised Roberts (10 February) that if he were still alive he would be in Kimberley, where the civilian population was urging Colonel Robert Kekewich to surrender, in five days.[76]

French's Cavalry Division consisted of three cavalry brigades and two brigades of mounted infantry, although the latter did not accompany them when they broke camp at 3 am on 11 March—a separate provisional brigade of mounted infantry was provided instead. Roberts gave an inspirational speech to French's brigade and regimental commanders. Rather than cross the Modder River directly (Kimberley lay around 25 miles north-east), they made an envelopment move: first over 20 miles south to Ramdam, then about 15 miles east to seize the Riet River Crossings, then about 25 miles (roughly north-north-east) to Klip Drift on the Modder, then another 20 miles north-west to Kimberley. This was to be accomplished across arid land in five days, with much of the travel by moonlight as it was the middle of summer. French carried only six days' rations for the men and five days' forage for the horses.[77]

The force left Ramdam at 2 am on 12 February, with only 4,000 horsemen rather than the 8,000 he had expected to have, but French felt he had to push on rather than wait for straggling units to catch up (the brigades' staffs were all new, and brigadiers only joined their units in the course of the march). De Kiel's Drift on the Riet was seized by mid afternoon—French ordered his cavalry to gallop for it as soon as he saw the way was clear—but the crossing was soon in what Haig called "an indescribable state of confusion" as Roberts had neglected to order priority for Cavalry Division baggage. Kitchener, arriving in the evening, ordered French to seize Waterval Drift, another crossing a few miles to the northwest where he had left a brigade masking a small Boer force under Christiaan de Wet. Although this was done, the advance could not be resumed until 10.30am—with the sun high in the sky—on 13 February, and accompanied by five baggage wagons which had managed to get through the logjam at De Kiel's Drift.[78]

Klip Drift

French's division moved in line of squadron columns across a five-mile wide front, halting between 12.30 and 1 pm at the well at Blauuwboschpan, where he left a garrison to hold until the infantry arrived. He brushed aside a small Boer force (perhaps 300 men) which attempted to block his path to the Modder River, but concerned that he might be attacked from the east by de Wet's main force, moved quickly at 2 pm to seize the crossings at Rondeval and Klip Drift (he aimed to at least threaten two crossings to avoid the delay which had happened at De Kiel's Drift). By 5 pm he was able to send a galloper to Roberts with the message that he was across the Modder. He had lost only three men wounded, although 40 horses had died of exhaustion and over 500 were incapable of further work. French then had to wait a day while Thomas Kelly-Kenny's 6th Infantry Division made a forced march from the Riet Crossings to the Modder Crossings, during which time Piet Cronje, believing French's advance to be a feint, missed an opportunity to reinforce the area.[79]

Equipped with three days' supplies, French resumed his advance at 9.30 am[80] on 15 February. At Abon's Dam, five miles north of the Modder, French sent his cavalry, supported by the fire of 56 guns, charging up a valley between two Boer held ridges. The charge was led by the 9th and 16th Lancers. The Boer riflemen, perhaps 600 in number, were able to achieve little at ranges of 1,000 yards.[81]

Amery's Times History later wrote "the charge at Klip Drift marks an epoch in the history of cavalry", arguing that French had "divined" that a cavalry charge made with "reckless, dare-devil confidence" could cut through a line of "unseen" enemy infantry who could have resisted a cautious attack by British infantry. The Official History called it "the most brilliant stroke of the war". He was also later praised by the cavalry writer Erskine Childers and by the German history of the campaign, which cited Klip Drift as evidence that cavalry could still charge infantry armed with magazine rifles. These claims were exaggerated. French had attacked a thinly-held part of the line, under cover of artillery fire and dust clouds, inflicting only 20 Boer casualties to sword and lance (as opposed to 60 at Elandslaagte). French himself saw it as a triumph of the cavalry spirit rather than a charge with cold steel per se.[82]

French entered Kimberley at 6 pm on 15 February, and was entertained at the Sanatorium by Cecil Rhodes, who soon persuaded him to relieve Kekewich, the military commander of the town. Holmes cites this as an evidence of French's tendency to take against people based only on superficial evidence.[83]

French was congratulated by Roberts, and Queen Victoria praised the cavalry's "brilliant success". For his success with the relief, French was promoted for distinguished service in the field on 21 February 1900, from substantive colonel to supernumerary major-general, and to local lieutenant-general.[84] Although French was later criticised for attacking the Boers around Kimberley on 16 February, Roberts' orders to pursue the retreating Cronje did not reach him owing to a cut telegraph line, and there is no evidence that Roberts made further efforts to contact him, although French heliographed to request orders.[85]

Paardeberg

Orders to pursue Cronje were hand-delivered to French at 10 pm on 16 February. French had only 1,500 mounted men and 12 guns fit for duty after their recent exertions—one regiment recorded on 17 February that only 28 of its horses could "raise a trot"—but, setting out at 3 am on 17 February, he and Broadwood led an advanced guard on a forced march, twice as fast as Cronje's force, to intercept them at 10 am as they tried to cross the Modder at Vendutie Drift (a distance of around 30 miles from Kimberley). Outnumbered three to one, and with another 2,000 Boers close by, French held his position long enough for the British infantry (6th and 9th Divisions) to catch up with Cronje's army at Paardeberg.[86]

French was too far away to interfere in the Battle of Paardeberg, although he sent a message urging caution—Kitchener ignored this and launched a disastrous frontal assault on 18 February. French spent the day holding off Boers who attempted to reinforce Cronje's force.[87] French also prevented the main Boer field army from escaping across the Modder River after the battle.[6]

Poplar Grove

Cronje at last surrendered his field army to Roberts on 27 February. On the morning of Klip Drift French had had 5,027 horses, but by 28 February exhaustion had reduced this number to 3,553. As Roberts prepared to advance on Bloemfontein, French was now, on 6 March, ordered to take his division and two Mounted Infantry Brigades and swing seventeen miles around the left flank of the Boer position at Poplar Grove on the Modder River, while Roberts' main force prepared to attack them from the front. Although French now had 5,665 horses again, many of these were of poor quality and sick, and he was short of fodder (horses were entitled to 3 lb of fodder per day, less than half of what they were getting a month earlier). On the basis of incorrect information from Colonel Richardson, Director of Supplies, who had not realised that sick horses were also entitled to fodder, Roberts gave French a dressing-down in front of his brigadiers, for consuming too many supplies. This was probably a turning point in their relationship.[88]

French led his men out of camp at 3 am on 7 March, amid confusion as Kelly-Kenny's Division, which was supposed to follow his, had started an hour earlier owing to unclear orders. The moon had set and French had to halt between 5 am and 5.45 am to await daybreak. By 7 am he had reached Kalkfontein Dam, a march of 12 miles, and spent 45 minutes watering his horses. By 7.30 am the Boers began to retreat from their position. Roberts later blamed French for failing to cut them off (and missing a chance to capture President Kruger). French argued that his horses were too weak to do more than trot, and that he was not strong enough as Kelly-Kenny's men had not yet arrived. He concentrated his Division for a pursuit, but even then was beaten off by the Boer rearguard. The Official History supported French's decision, although some felt that French was giving less than wholehearted co-operation after his unjustified public rebuke over the fodder issue. Holmes suggests that French carried out a plan in which he had no confidence because of Roberts' reputation for ruthlessness with unsatisfactory officers.[89]

French and Haig were sceptical about the riding abilities of Mounted Infantry, and felt that Roberts was wasting too many horses on them (Haig letter to his sister 16 March 1900) and that the cavalry had been "practically starving" since 11 February.[90][91] Bloemfontein fell on 13 March, and soon suffered an outbreak of typhoid.[92] In an implicit criticism of Roberts, French recorded (22 March 1900) that there "would be a grand opportunity for a great strategist at the head of affairs".[72] With Roberts' main army immobilised by disease at Bloemfontein, de Wet was still active making raids around the British periphery. Roberts eventually (20 March) sent French with a single cavalry brigade and some guns and Mounted Infantry in a vain attempt to intercept Olivier's column (numbering 6,000–7,000 men) at Thabanchu.[93][94] French made another raid to Karee Siding (29 March)—but until the middle of April he devoted most of his energies to inspecting the horses, many of them Argentinian, with which his division was being remounted.[94]

French was summoned to see Roberts (5 April 1900), who told him (5 April 1900) that the fighting at Poplar Grove proved that the future lay with Mounted Infantry. French wrote to Colonel Lonsdale Hale, former professor at Staff College (12 April 1900), for speaking out for the idea of cavalry against the "chatter and cackle" of its opponents, quoting the opinion of a German officer that Mounted Infantry were too poor at riding to fight effectively. French also clashed with Edward Hutton (14 April) when he asked for French's cavalry to be used to relieve his mounted infantry on outpost duty.[95]

Kroonstad

On the march to Pretoria (early May 1900) French's three brigades made up the left wing of Roberts' main thrust. (Other thrusts were by Mahon and Hunter over the Bechuanaland border, by Buller up from Natal and a semi-independent command under Hamilton, which might have been French's had he not been out of favour.) French lost another 184 of his still unacclimatised horses making—on Roberts' orders—a forced march to the Vet River.[96]

Botha was now making a stand along the River Zand, in front of the Orange Free State's temporary capital at Kroonstad. French was ordered to encircle Botha from the left, accompanied by Hutton's Mounted Infantry, while Broadwood struck from the right. Roberts over-ruled French's wish to make a wide encirclement and ordered a shallower one—this lost the advantage of surprise, and Botha pulled his forces back so that French ran into strong resistance on 10 May. Roberts now ordered French to pull back and make a deeper encirclement as he had originally proposed, with a view to cutting the railway behind Kroonstad. However, French's cavalry were now too tired, after an advance of forty miles, to achieve much, and Botha's army escaped. The Times History later praised French's rapidity of movement but criticised him—unfairly in Holmes' view—for failure to concentrate his forces.[97]

Transvaal

Roberts halted in Kroonstad to repair the railway and refit between 12 and 22 May. New horses arrived for French, but a third of them were unfit for action, and French and Hutton were only able to muster 2,330 effectives. French and Hamilton were now sent to threaten Johannesburg from the left.[98]

Roberts entered Johannesburg (31 May) and Pretoria (5 June), although without pressing Botha to a decisive battle in either case. French correctly dismissed talk of victory as premature, and continued to spend much of his time inspecting remounts—the job of Director of Remounts at Stellenbosch had been given to an incompetent and manic depressive officer, who eventually shot himself.[99] French played a key role at the victory over Louis Botha at Diamond Hill (11–12 June) in the north-east Transvaal. French, leading one of his own brigades in the usual encircling movement, came under heavy fire—a medical major was shot at his side—but held his position despite Roberts' permission to withdraw.[100]

In mid-July French operated against de Wet's guerrilla force around Pretoria, although he did not understand that this was an autonomous force, and advised Roberts that the best defence would be to continue to attack Botha's main army. French was then recalled to take part in another attack on Botha's army, but once again Roberts vetoed French's proposal of a deeper encirclement (on the British right this time), allowing Botha's army to escape.[101]

In late July 1900 Reginald Pole-Carew, commander of 11th Division, refused to accept French's orders. French at first asked to be relieved of responsibility for Pole-Carew's sector, but matters were patched up after what French described as a "somewhat stormy" meeting.[102]

Barberton

By August 1900 the Boer forces had been pushed into the northeast Transvaal. French was holding a position beyond Middelburg, maintaining moral ascendancy over the enemy by active probing and patrolling as he had around Colesberg earlier in the year. Roberts' plan was to push slowly eastward along the Delagoa Bay railway connecting Pretoria with the sea, while he ordered French to co-operate with Buller as he marched up from Natal. French wrote (24 August) "We sadly want someone in Chief Command here". Roberts at first refused French permission to concentrate the Cavalry Division for an outflanking move towards Barberton, an important Boer depot, and when he at last gave permission in late August Botha's force had retreated too far to be encircled as French had intended. Barberton is surrounded by 3,000 foot mountains, and French once again made a bold encircling move—first (9 September) south from the railway to Carolina, deceiving the Boer commandos that he intended to move southwest. He then moved back, and personally led his 1st Cavalry Brigade up a bridle path through the mountains ready to attack Barberton from the west. As soon as Henry Jenner Scobell, who had been sent around with two squadrons of the Greys, heliographed that he had cut the railway, French led his men down into the town. Scobell captured £10,000 in gold and notes, while French telegraphed to Roberts: "Have captured forty engines, seventy wagons of stores, eighty women all in good working order". Boer sniping from the hills ceased after French threatened to withdraw his men and shell the town.[103]

The war seemed over as Kruger left the country on 11 September 1900 (he sailed to the Netherlands from Portuguese Lourenço Marques on 19 November 1900).[104] French was promoted from supernumerary to substantive major-general on 9 October 1900, while continuing to hold the local rank of lieutenant-general.[105]

Under Kitchener

Johannesburg Area

French's colonials were sent home and replaced by regular Mounted Infantry. Roberts told French that the Cavalry Division was to be broken up, although he would retain "nominal command", and gave him command of Johannesburg Area.[6][104] On 13 December 1900 Jan Smuts and Koos de la Rey attacked a British force at Nooitgedacht. On 17 December 1900 Pieter Hendrik Kritzinger and Herzog invaded Cape Colony, hoping to stir up rebellion among the Cape Boers.[104] Although Kitchener had a paper strength of 200,000 men in early 1901, so many of these were tied down on garrison duty that French had only 22,000 men, of whom 13,000 were combatants, to fight 20,000 Boer guerrillas.[106]

By April 1901, after three months campaigning, French's eight columns had captured 1,332 Boers and 272,752 farm animals.[107] French was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB),[108] for his role in the conventional phases of the war (the award was dated 29 November 1900 and gazetted in April 1901, but French did not receive the decoration itself until an audience with King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace on 8 August 1902[109]).[110]

Cape Colony

On 1 June 1901 Kitchener ordered French to take command in Cape Colony.[6][111] He was ordered to use "severity" against captured rebels—this was intended to complement lenient treatment for those who surrendered voluntarily. Milner had already warned French at the time of the Colesberg operations (30 December 1899) not to treat every Cape Boer as a rebel unless it was proven so. French, who had lost several friends during the war, believed that stern measures would help end matters more quickly. French even forced the inhabitants of Middelburg to watch one hanging, incurring a concerned inquiry from St John Brodrick (Secretary of State for War), who was also vainly urging Kitchener to greater leniency.[111]

During this period of the war—conducting "drives" across the country for Boer guerrillas, and eventually dividing up the country with barbed wire and imprisoning Boer civilians in camps—French had to struggle with out-of-date information, and trying to maintain communications between British forces by telegraph, heliograph and dispatch rider.[112] Kritzinger was driven out of the Cape in mid-August 1901, and Harry Scobell captured Lotter's commando (5 September 1901). On 7 September Smuts defeated a squadron of Haig's 17th Lancers at Elands River Poort. Gideon Scheepers was captured on 11 October.[113]

Relations with Kitchener

French had a serious personality clash with the ascetic Kitchener, worsened by both men's obstinacy; French would later have a poor relationship with Kitchener during the First World War.[72] Although he had been unimpressed by his handling of Paardeberg, he seems to have broadly welcomed his appointment as Commander-in-Chief, not least because he was not as opposed as Roberts to the "arme blanche". In August 1900 Kitchener praised French to the Duke of York (later George V) and wrote to Roberts that French was "quite first rate, and has the absolute confidence of all serving under him, as well as mine".[114]

Kitchener wrote to Roberts praising French for the capture of Lotter's commando, but by 17 January 1902 he wrote to Roberts "French has not done much lately in the colony. I cannot make out why, the country is no doubt difficult but I certainly expected more." After meeting French at Nauuwport Kitchener recorded (14 February 1902) "he was quite cheerful and happy about progress made, though it appears to me slow". Ian Hamilton, now Kitchener's chief of staff, wrote that French was "very much left to his own devices ... he was one of the few men that Kitchener had trusted to do a job on his own".[115]

Kitchener later wrote of French "his willingness to accept responsibility, and his bold and sanguine disposition have relieved me from many anxieties".[116] Kitchener wrote of him to Roberts: "French is the most thoroughly loyal, energetic soldier I have, and all under him are devoted to him—not because he is lenient, but because they admire his soldier-like qualities".[117]

War ends

Roberts (now Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in London) ordered French to convene a committee to report on cavalry tactics; French replied (15 September 1901) that he was consulting his regimental commanders, and accepted that cavalry should fight dismounted with firearms, but that they needed a new and better sword.[118] French was appointed (23 October 1901) to command 1st Army Corps at Aldershot, in place of the disgraced Buller. French wrote to thank Roberts, to whose recommendation he guessed – correctly – that he owed the job, but also wrote to Buller, stressing that he had not been offered the position, but had been appointed to it by the King.[119]

The report on cavalry tactics (8 November 1901) demanded an effective rifle for cavalry rather than the existing carbine, but only as a "secondary" weapon. Roberts (10 November 1901) ordered cavalry to give up their steel weapons for the duration of the campaign, over the protests of French who argued that this was making the Boers tactically bolder.[118] In early November 1901 French, who was by now reliant on methodical operations and excellent field Intelligence, was infuriated by Kitchener's attempt to micromanage operations. In March French had expected the war to drag on until September 1902, but Kritzinger was captured in mid-November.[113][120] French continued to lobby about cavalry tactics, agreeing (21 February 1902) with the Mounted Infantry expert Maj-Gen Edward Hutton that it was "the bullet that kills" but that the important matter was "the moral power of cavalry".[121]

The war ended at the start of June 1902, after over a month of negotiations. French was ordered to return home on the same ship as Lord Kitchener;[122] they returned to Southampton on 12 July 1902,[110] and received an enthusiastic welcome with thousands of people lining the streets of London for their procession through the city.[123] At the peace he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in recognition of his services in South Africa,[124] an unusual award for a soldier. He also received honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge Universities and the freedom of a number of cities and livery companies.[110]

Edwardian period

Corps Commander, Aldershot

French was promoted to permanent lieutenant-general for distinguished service in the field on 22 August 1902.[125] In September 1902, he accompanied Lord Roberts and St John Brodrick, Secretary of State for War, on a visit to Germany to attend the German army maneuvers as guest of the Emperor Wilhelm.[126]

French took office as Commander of 1st Army Corps at Aldershot Command, from 15 September 1902.[127] He attracted the attention of Lord Esher when he testified before the Elgin Commission.[128] Esher reported to the King (27 February 1903) that he regarded French as the outstanding soldier of his generation, both as a field commander but also as a thinker. However, Balfour (Prime Minister) blocked French's appointment to the Esher Committee.[129]

French was proposed as a potential Chief of Staff in 1903–04. Esher wrote "he has never failed" while Admiral Fisher—who stressed French's excellent record in South Africa, his skill as a judge of men, and his openness to army-navy operations—wrote "plump for French and efficiency", although with growing friction over war planning, Fisher hoped that French would be an ally in opposing Army plans for deploying an expeditionary force to Europe. French's appointment was—to his relief, as he did not relish having to fight with Arnold-Forster over his mooted reforms—vetoed by King Edward VII, who thought him too junior for the post.[130] Esher pressed Neville Lyttelton, who was appointed instead, to give French as free a hand as possible.[131]

French had been insisting since January 1904 that, irrespective of what reforms the War Secretaries Brodrick or Arnold-Forster were pushing through, I Corps should be the Army's main strike force with at least one of its divisions kept up to strength for service overseas, and managed to force his view through the Army Council in August 1904.[131] French may have privately shared the doubts which others had about his intellectual capacity, but Esher wrote of him that his grasp of strategy and tactics broadened, and, although naturally gregarious, he became more aloof and solitary as he prepared himself for high command.[132] In 1904 French urged the adoption of the 18 pounder field gun on Esher. He also recognised the importance of howitzers.[133] At the 1904 Manoeuvres French commanded an "invasion force" which advanced inland from Clacton—many horses and supplies were lost, which apparently persuaded French that an enemy would find it hard to invade Britain successfully.[134] In October 1904 French won Fisher's approval with a paper on the strategic importance of the Dardanelles.[134]

French threatened resignation unless his aide de camp Major Algy Lawson, who had not attended Staff College, was appointed Brigade-Major of the 1st Cavalry Brigade. He suspected a War Office plot led by the rising staff officers Henry Rawlinson and Henry Wilson, whom at this stage he distrusted. Despite being advised by Esher that this was not a sufficiently serious matter to justify such obstinacy, French got his way (December 1904) by threatening to appeal to the King. He also got his way over a similar matter involving Esher's son Lt Maurice Brett, who served as French's ADC, and on this occasion did approach the King's secretary (February 1905).[135]

French was given General Officer Commanding-in-Chief status at Aldershot on 1 June 1905.[136] He was on the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1905, possibly because of his willingness to consider amphibious operations including at various times, in the Baltic and on the Belgian Coast. Philpott[137] discusses French's significant influence on pre-war strategic planning.[138] He generally confined his advice to practical questions such as the difficulties of keeping horses at sea for long periods.[134] French had a poor regard for staff officers and had poor relations with the general staff. At one meeting of the CID he became scarlet and speechless with rage while listening to Lyttelton proposing that Egypt could be defended by warships in the Suez Canal.[139]

On 19 December 1905 and 6 January 1906, as a result of the First Moroccan Crisis, French was one of a four-man committee convened by Esher to discuss war planning: the options were purely naval operations, an amphibious landing in the Baltic, or a deployment of an expeditionary force to France. At the second meeting French presented a plan for deployment to France or Belgium ten days after mobilisation, possibly mobilising on French territory to save time.[140][141] Although French helped to draw up deployment plans as asked, it is not entirely clear from the surviving documents that he wholeheartedly supported such a commitment to France ("WF"—"With France"—as this scheme was known) until he was eventually persuaded by Henry Wilson, and he did not entirely rule out an amphibious landing in the Baltic. He also maintained an interest in a possible deployment to Antwerp.[142]

French generally had good relation with Haldane, the new Secretary of State for War, but lobbied him against cutting two Guards battalions (the Liberals had been elected on a platform of retrenchment).[143] In February 1906 French told Major-General Grierson (Director of Military Operations) that he was to be Commander-in-Chief of the BEF during the next war, with Grierson as his chief of staff. He had meetings with Grierson throughout March until the Moroccan crisis was resolved.[144] French told the Daily Mail (12 May 1906) that a force of trained volunteers would deter an enemy invasion.[134] In June 1906 French still believed that another war scare might come soon, and in July he attended French Army manoeuvres in Champagne, by which he was impressed, although he was less impressed by the Belgian Army. On this trip he was accused of giving unauthorised interviews to the French press, after uttering what Grierson called "a few platitudes" to the Figaro correspondent.[145]

Haldane confirmed to Esher (26 September 1906) that French was to be Commander-in-Chief of the BEF during the next war.[146] He visited France unofficially in November 1906 in an attempt to improve his French, although he never became fluent in the language.[145] A Special Army Order of 1 January 1907 laid down that in the event of war Britain would send an Expeditionary force of six infantry and one cavalry division to assist the French.[147] French was promoted to full general on 12 February 1907.[148] In the summer of 1907 he entertained General Victor Michel, French Commander-in-Chief designate, at Aldershot to observe British manoeuvres.[149]

The cavalry controversy

French testified to the Elgin Commission that cavalry should be trained to shoot but that the sword and lance should remain their main weapons. Hutton wrote to French (1 April 1903) that cavalry should retain some shock capacity but that the real issue was recruiting "professional" officers in place of the present rich and aristocratic ones. French strongly disagreed, although he remained on friendly terms with Hutton and recognised that the expense of being a cavalry officer deterred many able young men.[121] The Adjutant-General's memorandum (10 March 1903) recommended the retention of the sword—which Roberts had wanted replaced by an automatic pistol—but not the lance. Roberts also chaired a conference on the topic six months later, at which Haig was the leading traditionalist. Haig's heavily traditional "Cavalry Training" appeared in 1904, leaning heavily on the 1898 Cavalry Drill Book which he had helped French to write, although with a "reforming" preface by Roberts.[150]

In response to a request from Arnold-Forster, French submitted a memorandum (7 March 1904) arguing that cavalry still needed to fight the old-fashioned way as a European War would begin with a "great cavalry battle". He also sent a copy to the King. In response to Roberts' claim that he wanted to give cavalry the ability to act independently, French wrote in the margin that the campaigns of early 1900 had seen cavalry acting independently, although he replied politely that their differences were not as great as Roberts seemed to think. Roberts had the support of Kitchener (who thought cavalry should be able to seize and hold positions, but not to roam about the battlefield looking for enemy cavalry), but he was away as Commander-in-Chief, India. French's memorandum was supported by Baden-Powell (Inspector-General of Cavalry), Sir Francis Grenfell (who commented that he had not spoken to any junior officer who agreed with Roberts) and by Evelyn Wood. In February 1905, after Roberts' removal as Commander-in-Chief, the Army Council authorised the publication of Haig's "Cavalry Training" but without Roberts' preface, although the lance was declared abolished as a weapon of war—a decision ignored by French, who allowed his lancer regiments at Aldershot to carry the lance in field training.[151]

The first edition of the Cavalry Journal appeared in 1906, promoted by C. S. Goldman, an admirer of French. It was put on an official basis in 1911.[152] Lieutenant General Friedrich von Bernhardi's Cavalry in Future Wars was published in 1906, with a preface by French, repeating his arguments that cold steel gave the cavalry moral superiority, and that the next war would see an opening clash of cavalry. French also claimed that Russian cavalry in the Russo-Japanese War had come off worse as they were too willing to fight dismounted—this was the opposite of the truth.[153][154] The new edition of Cavalry Training in 1907 reaffirmed that cold steel was the main weapon of the cavalry.[152] However, at the end of the 1908 Manoeuvres French criticised cavalry's poor dismounted work, and—to Haig's annoyance—declared that the rifle was cavalry's main weapon. He also noted that infantry lacked a doctrine for the final stages of their attack, as they closed with the enemy—something which was to prove a problem in the middle years of the Great War.[155] The lance was formally reinstated in June 1909. However, in his 1909 Inspection Report French again criticised cavalry's poor dismounted work.[156]

Although French believed that the "cavalry spirit" gave them an edge in action, his tendency to identify with his subordinates—in this case the cavalry, whose identity seemed under threat—and to take disagreements personally caused him to be seen as more of a reactionary than was in fact the case. In the event, cavalry would fight successfully in 1914: the "cavalry spirit" helped them to perform well on the Retreat From Mons, while they were still capable of fighting effectively on foot at First Ypres.[157]

There was general agreement that the greater size of battlefields would increase the importance of cavalry. The publication of Erskine Childers' War and the Arme Blanche (1910) with a preface by Roberts went some way to reinstating the reformers' case. Childers argued that there had been only four real cavalry charges in South Africa, inflicting at most 100 casualties by cold steel, but acknowledged that French, "our ablest cavalry officer", disagreed with him.[158] However, in September 1913 the Army Council decreed that Mounted Infantry would not be used in future wars and the two existing Mounted Infantry brigades were broken up.[159]

Inspector-General of the Army

After extensive lobbying by Esher, and with the King's support, French was selected as Inspector-General of the Army in November 1907.[160][161] The appointment was announced on 21 December 1907.[162] Irish MP Moreton Frewen demanded – apparently in vain – a Court of Inquiry into French's dismissal of his brother Stephen Frewen from command of the 16th Lancers during the Boer War, pointing out to Haldane that French was "an adulterer convicted in a court of law", for which offence "Haldane's late chief" had "drum(med) his late chief" out of public life.[163] French was also appointed a Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order in 1907.[6]

French openly opposed conscription, thinking Roberts' demand for a conscript army to defend against German invasion "absurd".[164] He was generally supportive of the new Territorial Army, although he had some doubts about the effectiveness of Territorial Artillery. In 1907–08 he sat on a CID committee to consider the risk of German invasion—it was decided to retain two divisions at home as a deterrent to invasion, until the Territorial Force was ready.[165] At the August 1908 manoeuvres, French's poor report ended the military career of Harry Scobell, who commanded the Cavalry Division on the exercise, despite being well connected, a personal friend of French, and a successful commander from the South African campaigns. French's reports showed great interest in trenches, machine guns and artillery. He also believed strongly that peacetime drill, both for infantry and for cavalry, was necessary to prepare men for combat discipline.[166] In the winter of 1908–09 French served on the "Military Needs of the Empire" sub-committee of the CID, which reaffirmed the commitment to France in the event of war.[149] He was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in the King's Birthday Honours 1909.[167] French courted unpopularity with some infantry officers by urging a doubling in the size of infantry companies. In the winter of 1909–10 he toured British troops in the Far East, and in the summer of 1910 he inspected the Canadian Militia, at the request of the Canadian Dominion administration. He declined to express an opinion on the mooted introduction of conscription in Canada, replying that the existing system of voluntary recruitment had not been tested for long enough yet.[168]

This period also saw the beginning of the feud between French and Smith-Dorrien, his successor at Aldershot with whom he had been on relatively cordial terms at the end of the Boer War. Smith-Dorrien annoyed French by insisting that cavalry improve their musketry, by abolishing the pickets which trawled the streets for drunken soldiers, by more than doubling the number of playing fields available to the men, by cutting down trees, and by building new and better barracks. By 1910 the feud was common knowledge throughout the Army. Smith-Dorrien, happily married to a young and pretty wife, also objected to French's womanising.[169]

French was made an Aide-de-Camp General to the King on 19 June 1911.[170] The Second Moroccan Crisis was occasion for French to push again for greater Army-Navy co-operation. Admiral Fisher, recently retired as First Sea Lord, wrote (20 August 1911) that French had been to see him "as the tool of Sir William Nicholson. I told him to go to Hell." On 23 August Henry Wilson carried a CID meeting with a lucid presentation of the Army's plans for deployment to France; Admiral Wilson's plans to land on the Baltic Coast were rejected. French spoke to the Navy Club that year on the need for co-operation between the two services.[171] The autumn 1911 manoeuvres were cancelled, supposedly because of shortage of water but in reality because of the war scare. French accompanied Grierson and the French military attaché Victor Huguet to France for talks with de Castelnau, Assistant Chief of the French General Staff (Wilson—Director of Military Operations since August 1910—had already been over for talks in July). On the journey, French talked of how Douglas and Paget would command armies under him in the event of war, with Grierson as chief of staff. Plans for British deployment were especially welcome as French war plans were in a state of flux, with Joffre having been appointed commander-in-chief designate on 28 July.[172] After his return from France in 1911 French inspected German cavalry manoeuvres in Mecklenburg, and was summoned from his bath to receive the Order of the Red Eagle. On presenting him with a signed photograph of himself the Kaiser told him: "You may have seen just how long my sword is: you may find it just as sharp".[173]

In January 1912 French attended the annual staff conference at Staff College, and was impressed by the quality of the discussion. However, he lectured staff officers that they should not consider themselves the superiors of regimental officers, but that their job was to provide the commander with impartial advice and then endeavour to carry out his wishes.[139]

Chief of the Imperial General Staff

He became Chief of the Imperial General Staff ("CIGS"—professional head of the Army) on 15 March 1912 although he neither had staff experience nor had studied at Staff College.[6][174] On his first day as CIGS (16 March 1912) he told his three directors (Wilson—Director of Military Operations, Murray—Director of Military Training and Kiggell—Director of Staff Duties) that he intended to get the Army ready for war. French was receptive to Wilson's wishes to explore co-operation with Belgium (although in the end the Belgian Government refused to co-operate and remained strictly neutral until the outbreak of war).[175][176] French had initially been suspicious of Wilson as a Roberts protégé, but in 1906 had supported Wilson's candidacy for Commandant of Staff College. By 1912 Wilson had become French's most trusted adviser.[171] On 8 November 1912, with the First Balkan War causing another war scare, Wilson helped French draw up a list of key officers for the Expeditionary Force: Haig and Smith-Dorrien were to command "armies", Allenby the cavalry division, and Grierson was to be chief of staff.[177]

In February 1913 Repington wrote a series of articles in The Times demanding conscription for home defence. The Prime Minister himself led the CID "Invasion Inquiry", on which French sat. The conclusions, which were not reached until early 1914, were that two divisions should be retained at home, reducing the size of the BEF. (French and Roberts had agreed with one another that one division would have sufficed.[177])

In April 1913, French told Wilson that he expected to serve as CIGS (extending his term by two years) until 1918, and to be succeeded by Murray.[178] In April 1913 the King told Seely that he was to make French a field marshal in the next honours.[146] He received the promotion on 3 June 1913.[6]

French's efforts "to get the Army ready for war" were hampered by budgetary constraints, and he was unsuited by temperament or experience for the job. French caused controversy by passing over four generals for promotion in the autumn of 1913, and angered some infantry officers by forcing through the changes to infantry battalions so that they comprised four large companies commanded by majors rather than eight small companies commanded by captains. French lobbied Seely for an increase in pay and allowances for officers, to widen the social base from which officers were recruited—this was enacted from 1 January 1914.[179]

In the summer of 1913 French, accompanied by Grierson and Wilson, again visited French manoeuvres in Champagne.[180] After the September 1913 Manoeuvres Repington wrote in The Times that French had found it difficult to defeat even a skeleton army.[180] Since 1904 French himself had to act as Director of the Annual Manoeuvres, so that although other officers had the chance to learn to handle divisions, he himself had little chance to learn to handle a force of several divisions. This lack of training may well have been factor in his poor performance in August 1914.[181] The BEF senior officers (French, Haig, Wilson, Grierson and Paget who had replaced Smith-Dorrien by then) met to discuss strategy on 17 November 1913. In his diary Wilson praised "Johnnie French" for "hitting out" at the Royal Navy over their poor transport arrangements, but recorded his concerns at French's lack of intellect and hoped there would not be a war just yet.[177][182]

Curragh incident

Plans for deployment

With Irish Home Rule about to become law in 1914, the Cabinet were contemplating military action against the Ulster Volunteers (UVF) who wanted no part of it, and who were seen by many officers as loyal British subjects. In response to the King's request for his views, French wrote that the army would obey "the absolute commands of the King", but he warned that some might think "that they were best serving their King and country either by refusing to march against the Ulstermen or by openly joining their ranks".[183] In December 1913, French recommended that Captain Spender, who was openly assisting the UVF, be cashiered "pour décourager les autres".[184]

With political negotiations deadlocked and intelligence reports that the Ulster Volunteers (now 100,000 strong) might be about to seize the ammunition at Carrickfergus Castle, French only agreed to summon Paget (Commander-in-Chief, Ireland) to London to discuss planned troop movements when Seely (Secretary of State for War) repeatedly assured him of the accuracy of intelligence that UVF might march on Dublin. French did not oppose the deployment of troops in principle but told Wilson that the government were "scattering troops all over Ulster as if it were a Pontypool coal strike".[185]

At another meeting on 19 March French told Paget not to be "a bloody fool" when he said that he would "lead his Army to the Boyne", although after the meeting he resisted lobbying from Robertson and Wilson to advise the Government that the Army could not be used against Ulster. That evening French was summoned to an emergency meeting at 10 Downing Street (he was requested to come in via the garden, not the front door) with Asquith, Seely, Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty), Birrell (Chief Secretary for Ireland) and Paget, where he was told that Carson, who had stormed out of a Commons debate, was expected to declare a provisional government in Ulster. French was persuaded by Asquith to send infantry to defend the artillery at Dundalk, and by Seely that a unionist coup was imminent in Ulster. No trace of Seely's intelligence survives. Seely reassured French, who was worried about a possible European war, that "large mobile forces of the Regular Army" would not be sent to Ireland unless needed, but he was sure that Ulster would support Britain in that event.[186]

Peccant paragraphs

The result was the Curragh incident, in which Hubert Gough and other of Paget's officers threatened to resign rather than coerce Ulster. French, advised by Haldane (Lord Chancellor) told the King on 22 March that Paget should not have asked officers about "hypothetical contingencies" and declared that he would resign unless Gough, who had confirmed that he would have obeyed a direct order to move against Ulster, was reinstated.[187]

French suggested to Seely that a written document from the Army Council might help to convince Gough's officers. The Cabinet text stated that the Army Council were satisfied that the incident had been a misunderstanding, and that it was "the duty of all soldiers to obey lawful commands", to which Seely added two paragraphs, stating that the Government had the right to use "the forces of the Crown" in Ireland or elsewhere, but had no intention of using force "to crush opposition to the Home Rule Bill".[188] Gough insisted on adding a further paragraph clarifying that the Army would not be used to enforce Home Rule "on Ulster", to which French added in writing "This is how I read it. JF CIGS". He may have been acting in the belief that the matter needed to be resolved quickly after learning from Haig that afternoon that all the officers of Aldershot Command would resign if Gough was punished.[6][189]

Asquith publicly repudiated the "peccant paragraphs". Wilson, who hoped to bring down the government, advised French to resign, as an officer could not be seen to break his word, even at the behest of politicians. Asquith at first wanted French to stay on as he had been "so loyal and well-behaved", but then changed his mind despite French drawing up two statements with Haldane, claiming that he had been acting in accordance with Haldane's statement in the House of Lords on 23 March. Seely also had to resign.[190] French resigned on 6 April 1914.[191]

Results

French had been made to look naive and overly friendly to the Liberal government. Most officers were Conservative and Ulster Unionist sympathisers, but, with a few exceptions (Kitchener and Wilson's party sympathies were well known), took pride in their loyalty to the King and professed contempt for party politics. French was thought by Margot Asquith to be a "hot Liberal".[192] By 1914, he was a personal friend of the Liberal ministers Winston Churchill and Jack Seely.[128] Meanwhile, Sir Edward Grey wrote "French is a trump, and I love him". After 1918 French became a Home Ruler, but at this stage he simply thought his duty to be ensuring that the Army obeyed the government's orders.[192]

As far back as 20 April 1913, Wilson recorded his concerns that French's friendship with Seely and unexpected promotion to Field Marshal were bringing him too close to the Liberals.[184] Throughout the affair French resisted pressure from Wilson to warn the government that the Army would not move against Ulster,[193] and he had an acrimonious telephone conversation (21 March) with Field Marshal Roberts in which he was told that he would share the blame if he collaborated with the Cabinet's "dastardly" attempt to coerce Ulster;[194][195] French for his part blamed Roberts for stirring up the Incident.[160] Esher approved of his resignation, as did H. A. Gwynne, who throughout the crisis had pressed French to tell the Cabinet that the Army would not coerce Ulster, and Godfrey Locker-Lampson.[196]

While sorting out some papers for his successor Charles Douglas, French told Wilson that Asquith had promised him command of the BEF in the event of war, although nobody realised how quickly this would come.[197] Margot Asquith wrote that he would soon be "coming back", suggesting that Asquith may have promised to appoint French Inspector-General. Churchill described him as "a broken-hearted man" when he joined the trial mobilisation of the fleet in mid-July. French was still seen as a potential Commander-in-Chief of the BEF, although even in early August French himself was uncertain that he would be appointed.[196][198][199]

Commander-in-Chief, BEF

1914: BEF goes to war

Mobilisation and deployment

The "Precautionary Period" for British mobilisation began on 29 July, the day after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. French was summoned by Sir Charles Douglas (CIGS) and told (30 July) he would command the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).[7][200] There was no other serious candidate for the position.[201] He was first briefly re-appointed Inspector-General of the Army (1 August).[202] Sir John spent much of 2 August in discussions with French Ambassador Paul Cambon.[200] British mobilisation began at 4 pm on 4 August,[203] and Britain joined the war at midnight.[204]

French attended the War Council at 10 Downing Street (5 August), and there presented the War Office plans (drawn up by Wilson) to send the BEF to Maubeuge, although he also suggested that as British mobilisation was lagging behind France's it might be safer to send the BEF to Amiens (also the view of Lord Kitchener and Lt.-General Sir Douglas Haig). French also suggested that the BEF might operate from Antwerp against the German right flank, similar to schemes which had been floated in 1905–06 and reflecting French's reluctant acceptance of the continental commitment. This suggestion was dropped when Churchill said the Royal Navy could not guarantee safe passage.[200] Kitchener, believing the war would be long, decided at Cabinet (6 August) that the BEF would consist of only 4 infantry divisions (and 1 cavalry); French, believing the war would be short, demanded 5 infantry divisions but was over-ruled at another War Council that afternoon. Embarkation began on 9 August.[203]

On 12 August, French, Murray, Wilson and the French liaison officer Victor Huguet met at French's house at Lancaster Gate and agreed to concentrate at Maubeuge, and after another meeting with Kitchener (who had had an argument with Wilson on 9 August—given Wilson's influence over French, this served to worsen relations between French and Kitchener), who still preferred to concentrate further back at Amiens, they left to obtain the Prime Minister's agreement.[205]

French crossed to France on 14 August.[203] President Poincaré, meeting French on 15 August, commented on his "quiet manner ... not very military in appearance" and thought that one might mistake him for a plodding engineer rather than a dashing cavalry general. French told Poincare that he would not be ready until 24 August, not 20 August as planned.[206] French also met Messimy (French War Minister) and Joffre (16 August).[207] Sir John's orders from Kitchener were to co-operate with the French but not to take orders from them, and given that the tiny BEF (about 100,000 men, half of them regulars and half reservists) was Britain's only army, to avoid undue losses and being exposed to "forward movements where large numbers of French troops are not engaged" until Kitchener had had a chance to discuss the matter with the Cabinet.[208]

Clash with Lanrezac

The Siege of Liège ended when the last of the Belgian fortresses fell on 16 August and most of the remaining Belgian troops were soon besieged in Antwerp, opening Belgium to the German advance. Previously ardent and bombastic, French became hesitant and cautious, giving different answers about the date when the BEF could be expected to begin operations in the field.[209][210]

At his meeting with Joffre (16 August), French had been advised to hurry up and join in Lanrezac's offensive, as he would not wait for him to catch up.[211] French met General Charles Lanrezac, commanding the French Fifth Army on his right, at Rethel (17 August)—they were met by Lanrezac's Chief of Staff Hely d'Oissel, with the words: "At last you're here: it's not a moment too soon. If we are beaten we will owe it to you". They conferred in private despite the fact that Lanrezac spoke no English and Sir John could speak little French, Wilson being eventually called over to translate. French informed Lanrezac that his forces would not be ready until 24 August, three days later than promised. The French cavalry under André Sordet, which Sir John had previously asked Joffre in vain to be placed under his command, were further north trying to maintain contact with the Belgians. Sir John, concerned that he had only four infantry divisions rather than the planned six, wanted to keep Allenby's cavalry division in reserve and refused Lanrezac's request that he lend it for reconnaissance in front of the French forces (Lanrezac misunderstood that French intended to use the British cavalry as mounted infantry). French and Lanrezac came away from the meeting with a poor relationship. At the time French wrote in his diary that Lanrezac was "a very capable soldier", although he claimed otherwise in his memoirs 1914. Besides their mutual dislike he believed Lanrezac was about to take the offensive, whereas Lanrezac had in fact been forbidden by Joffre to fall back and wanted the BEF moved back further to clear roads for a possible French retreat.[209][210][212][213]

French's friend General Grierson, GOC II Corps, had died suddenly on the train near Amiens and French returned to GHQ on 17 August, to find that Kitchener had appointed Lieutenant-General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien to command, knowing that French disliked him, rather than Plumer (French's choice) or Hamilton (who asked for it).[210][214]

Spears arrived at GHQ (21 August) and reported to Wilson (French was out visiting Allenby) that Lanrezac did not want to leave his strong position (behind the angle of the Rivers Sambre and Meuse) and "had declaimed at length on the folly of attack". Holmes believes French was receiving very bad advice from Wilson at this time, in spite of good air and cavalry intelligence of strong German forces. French set out for Lanrezac's HQ (22 August) but by chance met Spears on the way, who told him that Lanrezac was in no position to attack after losses the previous day at the Battle of Charleroi, which Sir John did not quite believe and that Lanrezac was out at a forward command post. Brushing aside Spears' arguments that another meeting with Lanrezac would help, French cancelled his journey and returned to GHQ; "relations with Lanrezac had broken down", writes Holmes, because Sir John saw no point in driving for hours, only to be insulted once again in a language he did not quite understand.[215][216]

French was then visited again over dinner by Spears, who warned him that the BEF was now 9 miles (14 km) ahead of the main French line, with a gap of 5 miles (8.0 km) between the British right and Lanzerac's left, exposing the BEF to potential encirclement. Spears was accompanied by George Macdonogh, who had deduced from air reconnaissance that the BEF was facing three German corps, one of which was moving around the BEF left flank (only three French territorial divisions were to the left of the BEF; Sordet's French cavalry corps was on its way to the British left but its horses were exhausted). Sir John cancelled the planned advance. Also that evening a request arrived from Lanrezac, that the BEF attack the flank of the German forces which were attacking Fifth Army, although he also—contradicting himself—reported that the BEF was still in echelon behind his own left flank, which if true would have made it impossible for the BEF to do as he asked. French thought Lanrezac's request unrealistic but agreed to hold his current position for another 24 hours.[215][217]

Mons