Mesh analysis (or the mesh current method) is a circuit analysis method for planar circuits. Planar circuits are circuits that can be drawn on a plane surface with no wires crossing each other. A more general technique, called loop analysis (with the corresponding network variables called loop currents) can be applied to any circuit, planar or not. Mesh analysis and loop analysis both make systematic use of Kirchhoff’s voltage law to arrive at a set of equations guaranteed to be solvable if the circuit has a solution.[1] Mesh analysis is usually easier to use when the circuit is planar, compared to loop analysis.[2]

Mesh currents and essential meshes

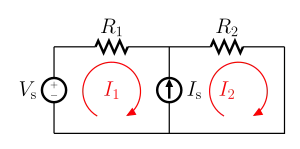

Mesh analysis works by arbitrarily assigning mesh currents in the essential meshes (also referred to as independent meshes). An essential mesh is a loop in the circuit that does not contain any other loop. Figure 1 labels the essential meshes with one, two, and three.[3]

A mesh current is a current that loops around the essential mesh and the equations are solved in terms of them. A mesh current may not correspond to any physically flowing current, but the physical currents are easily found from them.[2] It is usual practice to have all the mesh currents loop in the same direction. This helps prevent errors when writing out the equations. The convention is to have all the mesh currents looping in a clockwise direction.[3] Figure 2 shows the same circuit from Figure 1 with the mesh currents labeled.

Solving for mesh currents instead of directly applying Kirchhoff's current law and Kirchhoff's voltage law can greatly reduce the amount of calculation required. This is because there are fewer mesh currents than there are physical branch currents. In figure 2 for example, there are six branch currents but only three mesh currents.

Setting up the equations

Each mesh produces one equation. These equations are the sum of the voltage drops in a complete loop of the mesh current.[3] For problems more general than those including current and voltage sources, the voltage drops will be the impedance of the electronic component multiplied by the mesh current in that loop.[4]

If a voltage source is present within the mesh loop, the voltage at the source is either added or subtracted depending on if it is a voltage drop or a voltage rise in the direction of the mesh current. For a current source that is not contained between two meshes (for example, the current source in essential mesh 1 in the circuit above), the mesh current will take the positive or negative value of the current source depending on if the mesh current is in the same or opposite direction of the current source.[3] The following is the same circuit from above with the equations needed to solve for all the currents in the circuit.

Once the equations are found, the system of linear equations can be solved by using any technique to solve linear equations.

Special cases

There are two special cases in mesh current: currents containing a supermesh and currents containing dependent sources.

Supermesh

A supermesh occurs when a current source is contained between two essential meshes. The circuit is first treated as if the current source is not there. This leads to one equation that incorporates two mesh currents. Once this equation is formed, an equation is needed that relates the two mesh currents with the current source. This will be an equation where the current source is equal to one of the mesh currents minus the other. The following is a simple example of dealing with a supermesh.[2]

Dependent sources

A dependent source is a current source or voltage source that depends on the voltage or current of another element in the circuit. When a dependent source is contained within an essential mesh, the dependent source should be treated like an independent source. After the mesh equation is formed, a dependent source equation is needed. This equation is generally called a constraint equation. This is an equation that relates the dependent source’s variable to the voltage or current that the source depends on in the circuit. The following is a simple example of a dependent source.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Hayt, William H., & Kemmerly, Jack E. (1993). Engineering Circuit Analysis (5th ed.), New York: McGraw Hill.

- 1 2 3 4 Nilsson, James W., & Riedel, Susan A. (2002). Introductory Circuits for Electrical and Computer Engineering. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

- 1 2 3 4 Lueg, Russell E., & Reinhard, Erwin A. (1972). Basic Electronics for Engineers and Scientists (2nd ed.). New York: International Textbook Company.

- ↑ Puckett, Russell E., & Romanowitz, Harry A. (1976). Introduction to Electronics (2nd ed.). San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.