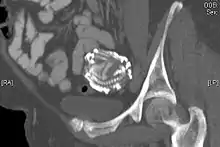

A lithopedion (also spelled lithopaedion or lithopædion; from Ancient Greek: λίθος "stone" and Ancient Greek: παιδίον "small child, infant"), or stone baby, is a rare phenomenon which occurs most commonly when a fetus dies during an abdominal pregnancy,[1] is too large to be reabsorbed by the body, and calcifies on the outside as part of a foreign body reaction, shielding the mother's body from the dead tissue of the fetus and preventing infection.

Lithopedia may occur from 14 weeks gestation to full term. It is not unusual for a stone baby to remain undiagnosed for decades and to be found well after natural menopause; diagnosis often happens when the patient is examined for other conditions that require being subjected to an X-ray study. A review of 128 cases by T.S.P. Tien found that the mean age of women with lithopedia was 55 years at the time of diagnosis, with the oldest being 100 years old. The lithopedion was carried for an average of 22 years, and in several cases, the women became pregnant a second time and gave birth to children without incident. Nine of the reviewed cases had carried lithopedia for over 50 years before diagnosis.[2]

According to one report there are only 300 known cases of lithopedia[3] recorded over 400 years of medical literature. While the chance of abdominal pregnancy is one in 11,000 pregnancies, only between 1.5 and 1.8 percent of these abdominal pregnancies may develop into lithopedia.[4]

History

The earliest known lithopedion was found in an archaeological excavation at Bering Sinkhole, on the Edwards Plateau in Kerr County, Texas, and dated to 1100 BC.[5] Another early example may have been found in a Gallo-Roman archaeological site in Costebelle, southern France, dating to the 4th century.[6]

The condition was first described in a treatise by the Spanish Muslim physician Abū al-Qāsim (Abulcasis) in the 10th century.[5] By the mid-18th century, a number of cases had been documented in humans, sheep and hares in France and Germany. In a speech before the French Académie Royale des Sciences in 1748, surgeon Sauveur François Morand used lithopedia both as evidence of the common nature of fetal development in viviparous and oviparous animals, and as an argument in favor of caesarean section.[7]

An archeological team did a "differential diagnosis of a calcified cyst found in an 18th century female burial site at St. Nicholas Church cemetery" in Czechia and determined the mass was likely either a case of lithopedion or fetus in fetu.[8]

In 1880, German physician Friedrich Küchenmeister reviewed 47 cases of lithopedia from the medical literature and distinguished three subgroups: Lithokelyphos ("Stone Sheath"), where calcification occurs on the placental membrane and not the fetus; Lithotecnon ("Stone Child") or "true" lithopedion, where the fetus itself is calcified after entering the abdominal cavity, following the rupture of the placental and ovarian membranes; and Lithokelyphopedion ("Stone Sheath [and] Child"), where both fetus and sac are calcified. Lithopedia can originate both as tubal and ovarian pregnancies, although tubal pregnancy cases are more common.[2]

Reported cases

Before 1900

| Patient (age at time of diagnosis) |

Location | Date of pregnancy | Date of diagnosis (case duration) |

Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unknown | Cordoba, II Umayyad Caliphate | Unknown | Late 10th century | The case referred by Abulcasis. The patient was pregnant in two separate occasions but never gave birth. "A long time" after, she developed a large swelling in the navel area, that turned into a suppurating wound and would not heal despite receiving treatment. This continued until Abulcasis removed several fetal bones through the wound, which initially shocked Abulcasis, as he had never known of a similar case. The patient largely recovered her health, but she continued to suppurate through the wound.[9] |

| Lodovia "LaCavalla" | Pomponischi, Duchy of Mantua | Unknown | 1540 | The patient had a failed pregnancy followed by a successful one, after which she fell sick and rapidly lost weight. Christopher Bain, a travelling surgeon, practised an incision and extracted "the skeleton of a male child". She recovered fully and went on to have four more children.[9] |

| Colombe Chatri (68)* | Sens, Kingdom of France | 1554 | 1582 (28 years) |

Chatri became pregnant for the first time at 40, but never gave birth after breaking her water and going through labor pains. She was bedridden for the next three years, during which she noticed a hard tumor on her lower abdomen, and complained of tiredness and abdominal pains for the rest of her life. After her death, her widower requested two physicians to examine her body, who discovered a fully formed, petrified baby girl, with remains of hair and a single tooth.[2] By 1653 the lithopedion had come into the possession of King Frederick III of Denmark, who consented to show it to Thomas Bartholin, but not to examine it further.[7] |

| Unknown | Pont-à-Mousson, Lorraine, Holy Roman Empire | 1629 | 1659 (30 years) |

[7][10] |

| Unknown | Dôle, Franche-Comté, Spanish Empire | 1645 | 1661 (16 years) |

[7][10] |

| Marguerite Mathieu (62)* | Toulouse, Kingdom of France | 1653 | 1678 (25 years) |

Originally from the Gascon village of Viulas near Lombez, Mathieu gave birth to ten children but only three survived infancy. At 37, she became pregnant, carried to full term and broke her water for the eleventh time, but never gave birth despite the efforts of a physician. She suffered from acute abdominal pain for two months, vaginal bleeding for five months, and felt discomfort for the rest of her life. This only eased when she laid on her back, making her bedridden and she experienced periodic paroxysmal attacks. Her case became notorious and her symptoms were popularly attributed to a spell cast by a sorceress whom Mathieu had rejected as a midwife. She consented to a public, three-day long necropsy after her death, which was attended by four doctors, three surgeons and their assistants. They found the calcified umbilical cord, placenta and a fully formed baby boy inside that weighed 3,916 grams (8 lb 10 oz). The lithopedion was found floating in white, odorless pus, which made it semi-mobile and would explain Mathieu's claim that she could still feel the baby moving inside her. The lithopedion was extensively described and pictured in a published memoir by François Bayle, one of the doctors present.[7] |

| Unknown | Leeuwarden, United Provinces | c. 1692 | 1694 (21 months) |

A 21-month-old, intra-tubarian lithopedion was removed successfully from a living woman by Cyprien, a teacher of anatomy and surgery at the University of Franeker.[7] |

| Anna Mullern (94)* | Leinzell, Swabia, Holy Roman Empire | 1674 | 1720 (46 years) |

Aged 48, Mullern became pregnant, broke her water and went through labor pains for seven weeks without giving birth, retaining a swollen belly afterwards. She would suffer pain when exercising for the rest of her life, but she was able to become pregnant again and gave birth to healthy dizygotic twins. Convinced that she had been pregnant and carried the previous baby with her still, Mullern made the local physician and surgeon swear that they would open her body after her death. The physician did not survive her, but the elderly surgeon fulfilled his promise with the help of his son, finding "a hard mass of the form and size of a large Ninepin-Bowl" that contained a petrified fetus inside. It was examined by George I of Britain's personal physician Johann Georg Steigerthal, who wrote an account of it.[11] |

| Marie de Bresse (61)* | Joigny, Kingdom of France | 1716 | 1747 (31 years) |

Patient was in her second pregnancy after a natural abortion four years before. De Bresse took it to full term and underwent labor pains for two days, but never had vaginal dilatation. After the midwife gave up, an assembly of doctors and physicians from Troyes decided unanimously that the best was to perform a cesarean section, but she refused. She continued having abdominal pains for a month and could not resume work before eight. She never regained her period and continued lactating for thirty years. At 61, she was hospitalized for chest inflammation and died shortly after. The autopsy found an oval mass the size of a man's head embedded in her right fallopian tube, which weighed 8 pounds (3.6 kg) and contained a fully formed baby boy with hair, two incisors and remains of amniotic fluid. The envelope was not fully calcified.[12] |

| Mrs. Ball | London, Kingdom of Great Britain | 1741 | 1747 (6 years) |

"A dead infant" was found in the belly, outside of the womb, during an autopsy performed at the request of the patient. In the time between her failed pregnancy and her own death, Ball became pregnant and gave birth four times without complications.[12] |

| Randi Jonsdatter (50) | Kvikne, Hedmark, Denmark-Norway | 1803 | 1813 (10 years) |

Patient "gave birth" to a petrified baby divided in two parts, through a cut performed over Jonsdatter's belly button. She lived for many years after without any further problems.[13] |

| Rebecca Eddy (77)* | Frankfort, New York, United States | c. 1802 | 1852 (c. 50 years) |

Aged 27 and in her first pregnancy, Eddy went through what seemed to be labor pains after an accident with a large kettle over the fire, but the pains disappeared a few days later and she never gave birth. William H. H. Parkhurst examined her in 1842, noting the "largeness, hardness and irregularity" of her abdominal lump; he would perform her autopsy in front of 20 witnesses when she died a decade later. During the process Parkhurst found "a perfect formed child... weighing 6 pounds avoirdupois (2.7 kilograms)" who "had no adhesions or connections with the mother except to the Fallopian tubes, and the blood vessels which nourished it, and which were given off from the mesenteric arteries... the child was almost floating in the abdomen."[14] |

| Sophia Magdalena Lehmann (87)* | Zittau, German Empire | 1823 | 1880 (57 years) |

Lehmann, a widow from Olbersdorf, was diagnosed with lithopedion in 1823 by an obstetrician in Zittau, and treated by Küchenmeister before he moved to Dresden in 1859. Upon her death, Küchenmeister performed her autopsy and used her case to describe the lythokeliphos category.[7] |

- * After death of the patient.

After 1900

| Patient (age at time of diagnosis) |

Location | Date of pregnancy | Date of diagnosis (case duration) |

Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mrs. C (31) | London & Devon, Great Britain | Jan–June 1929 (presumed) | 1930-02-24 (seven months) |

"Skiagram confirmed...the fœtus was lying among coils of small intestine"[15] |

| Unknown | Yazoo City, Mississippi, United States | c. 1930 | 1933 (c. 2–3 years) |

While performing surgery to remove a tumor on a woman from Inverness, Mississippi, Dr. L.T. Miller discovered the lithopedion "that had become petrified to the right of the tumor."[16] |

| Unknown (54) | Jamaica | 1957 | 1966 (9 years) |

The patient, who had given birth previously, had a swollen belly and noted movement inside, but did not believe she was pregnant because she continued to menstruate, albeit irregularly. The movements ceased shortly after being admitted to a Kingston hospital but the bleeding and pain continued until she was operated on 8 months later. Although her belly had deflated, the patient still felt a mass inside, but was dismissed by her doctor. The pain resumed years later, when the woman had migrated to Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and she was relieved of an oval-shaped, calcified mass of 8 × 4 x 3 cm.[17] |

| Unknown (60) | Thailand | 1959 | 1987 (28 years) |

A 60-year-old woman presented with an abdominal mass that she had had for 28 years, with no additional symptoms being reported. Scans revealed the nature of the mass to be a lithopedion. Surgical removal yielded a well-preserved calcified dead foetus weighing 1060 grams and the patient recovered uneventfully.[18] |

| Unknown (76) | Republic of China | 1950 | 1999 (49 years) |

Patient was originally diagnosed with a benign tumor in 1950, but refused the operation to extract it.[19] |

| Unknown (67) | Washington, United States | 1962 | 1999; not extracted (37 years) |

Admitted with abdominal pain, the patient reported to have "missed the baby" during a pregnancy 37 years prior, but refused intervention. She suffered no consequences and carried a second intrauterine pregnancy to term with no problem. Pain episode resolved and patient released without attempt of extraction.[20] |

| Unknown (40) | Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil | 1982 | 2000 (18 years) |

The "patient reported regular abdominal growth and healthy fetal activity from a pregnancy that happened 18 years earlier. She had never done pre-natal follow-up. In the third trimester, she felt strong cramps in the lower abdomen at the same time that fetal activity disappeared. She had not looked for medical assistance and some weeks later she eliminated a dark red mass through the vagina with a placental appearance. She had experienced the characteristic modifications of breast lactation. The abdomen had started to decrease but retained an infra-umbilical mass of about 20 centimeters in diameter, mobile and painless."[3] |

| Zahra Aboutalib (75) | Grand Casablanca, Morocco | 1955 | 2001 (46 years) |

Probably the most documented case. Heavily pregnant, Aboutalib went through labor pains for 48 hours at her home before being taken to a hospital, where she was scheduled for a cesarean section. However, after witnessing another young woman dying during the procedure she feared for her life and fled the hospital. The pain ceased days later and did not return for 46 years, when the still unidentified lithopedion was initially mistaken for an ovarian tumor. Aboutalib never bore children again after her ectopic pregnancy, but adopted three.[21][22][23] |

| Unknown (80) | South Africa | 1960 | 2001 (c. 40 years) |

An 80-year-old woman presented in the outpatient department with severe abdominal pain. Ultrasound examination revealed a large echogenic mass (20 x 20 cm) in the right upper quadrant. An abdominal x-ray demonstrated the skeleton of a fully developed extrauterine fetus. It is presumed from the patient's history that this fetus was present for at least 40 years. Radiography revealed a fetus shrouded in a mantle of calcification. The fetus was hyper-flexed with other signs of "intrauterine" death. Fetal dentition charts dated the fetus at 34 weeks, the epiphyses being obscured by extensive calcification. In addition to subcutaneous calcification there was extensive visceral and intracranial calcification.[24] |

| Unknown (63) | Daegu, South Korea | 1961 | 2001 (40 years) |

Postterm abdominal pregnancy extended beyond nine months, after which fetal movement ceased and the mother suffered from vaginal bleeding, but never gave birth. The patient became pregnant again and gave birth to a healthy baby girl two years later.[25] |

| Unknown (33) | Ghana | 1990 | 2002 (12 years) |

Third pregnancy after two natural miscarriages. Patient experienced abdominal pain, bilateral tubal blockage and infertility.[26] |

| Unknown (40) | Burla, Odisha, India | 1999 | 2007 (8 years) |

Only known case of twin lithopedia. One embryo grew in each ovary until both died 5 months into development; the patient assumed she had suffered a normal natural miscarriage. She had pain in both sides of the lower abdomen through the following 8 years, when it was joined by abdominal distention, vomiting and intestinal constipation.[4] |

| Unknown (31) | Curaren, Francisco Morazán, Honduras | 1995 | 2008 (13 years) |

The ectopic pregnancy happened shortly after the birth of the patient's first child. Afterwards she was pregnant seven times more, giving birth to her last child just two months before the diagnosis.[27] |

| Unknown (68) | Northern Cape, South Africa | 1986 | 2011; not extracted (25 years) |

Fourth pregnancy, when the patient was aged 44. Resulted in infertility, which was taken for a case of early menopause, but was otherwise asymptomatic.[28] |

| Unknown (37) | Malongo, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 2009 | 2011 (3 years) |

Patient went through the same experience as in her previous eight pregnancies, but "the baby never came out". Surgeons retrieved a calcified 32 weeks fetus from the abdominal cavity; the ovaries and uterus were intact and the patient had her period regularly.[29] |

| Unknown (32) | Santa Clara, Waspam, Nicaragua | 2010 | 2011 (35 weeks) |

Patient in her third pregnancy. Was hospitalized because she did not feel fetal movement anymore.[30] |

| Antamma (70) | Mominpur, West Bengal, India | 1977 | 2012 (35 years) |

Admitted to hospital after complaining of stomach pain for some time. The patient had delivered three healthy children after this incomplete pregnancy.[31] |

| Huang Yijun (92) | People's Republic of China | 1948 | 2013 (65 years) |

Longest known case. The patient was informed that the fetus had died inside her in 1948, but she did not remove it earlier because she lacked the money.[32] |

| Unknown (82) |

Bogota, Colombia | 1973 | 2013; not extracted (40 years) |

Patient originally thought to be suffering from gastroenteritis but an abdominal radiography discovered a calcified fetus in her abdomen.[33] |

| Unknown (70) |

Tamil Nadu, India | 1962 | 2014; not extracted (52 years) |

Patient presented with history of purulent discharge per vagina. Treated as purulent inflammation of cervix after biopsy report. Subsequently, condition resolved followed by history of pain and breathlessness. On radiography, it was found that the patient had a lithopedion fetus in her abdomen. She was asymptomatic through her reproductive life. |

| Joaquina Costa Leite (84) |

Natividade, Tocantins State, Brazil | 1970 | 2014; not extracted (44 years) | Patient was having abdominal pain, when doctors discovered the fetus. She claimed to have been pregnant more than 40 years prior. After extreme pain back then, she saw a local traditional healer who gave her medication that ended the pain, and – she had assumed – miscarried the baby.[34] |

| Estela Meléndez (90) |

San Antonio, Chile | 1965 | 2015; not extracted (50 years) |

A 2 kg (4.4 lb) calcified fetus was discovered in the abdomen of a 90-year-old Chilean woman. The discovery was made during an X-ray examination after the lady was brought to the hospital following a fall. The lithopedion, which is believed to have been there for 50 years, was so large and developed, it occupied the whole abdominal cavity. The fetus was not removed on the grounds of the patient's age.[35] |

| Kantabai Thakre (60) |

Nagpur, India | 1978 | 2015 (37 years) | Thakre was warned that her pregnancy was ectopic and would not be successful, but she was afraid of surgery and returned home, where she took remedies to alleviate the pain only. The pains disappeared a few months later, but they returned after 37 years. Fearing cancer, Thakre sought hospital treatment, was diagnosed and had the fetus remains extracted.[36] |

| Hawa Adan (31) |

Mandera, Kenya | 2007 | 2020 (13 years) | Adan, a 31-year-old Ethiopian woman, unsuccessfully sought medical treatment in her native country for an abdominal swelling. Subsequently, she moved to Mandera County Referral Hospital in northern Kenya where a CT scan diagnosed her with lithopedion. Doctors at the hospital successfully operated on her to remove the male infant stone baby.[37] |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Spitz, Werner U.; Spitz, Daniel J., eds. (2006). "Chapter III: Time of Death and Changes after Death. Part 1: Anatomical Considerations.". Spitz and Fisher's medicolegal investigation of death : guidelines for the application of pathology to crime investigation (4th ed.). Springfield, Ill.: Charles C. Thomas. pp. 87–127. ISBN 0398075441. OCLC 56614481.

- 1 2 3 Bondeson, Jan (2000). The two-headed boy, and other medical marvels. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0801437679. OCLC 43296582.

- 1 2 Passini, Renato; Knobel, Roxana; Parpinelli, Mary Ângela; Pereira, Belmiro Gonçalves; Amaral, Eliana; de Castro Surita, Fernanda Garanhani; de Araújo Lett, Caio Rogério (November 2000). "Calcified abdominal pregnancy with eighteen years of evolution: case report". São Paulo Medical Journal. 118 (6): 192–94. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802000000600008. PMID 11120551.

- 1 2 Mishra, JM; Behera, TK; Panda, BK; Sarangi, K (September 2007). "Twin lithopaedions: a rare entity" (PDF). Singapore Medical Journal. 48 (9): 866–68. PMID 17728971. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- 1 2 Rothschild, BM; Rothschild, C; Bernent, LG (July 1993). "Three-millennium antiquity of the lithokelyphos variety of lithopedion". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 169 (1): 140–41. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90148-c. PMID 8333440.

- ↑ Rose, Mark (January–February 1997). "Origins of Syphilis". Archaeology Magazine. Vol. 50, no. 1. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stofft, Henri (1986). "Un lithopédion en 1678" [One case of Lithopaedion in 1678] (PDF). Histoire des sciences médicales (in French). 20 (3): 267–286. PMID 11634084. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ Kwiatkowska, Barbara; Bisiecka, Agata; Pawelec, Łukasz; Witek, Agnieszka; Witan, Joanna; Nowakowski, Dariusz; Konczewski, Paweł; Biel, Radosław; Król, Katarzyna; Martewicz, Katarzyna; Lissek, Petr; Vařeka, Pavel; Lipowicz, Anna (2 July 2021). "Differential diagnosis of a calcified cyst found in an 18th century female burial site at St. Nicholas Church cemetery (Libkovice, Czechia)". PLOS ONE. 16 (7): e0254173. Bibcode:2021PLoSO..1654173K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0254173. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8253445. PMID 34214114.

- 1 2 Schumann, Edward A. (1921). Extra-uterine pregnancy. Gynecological and obstetrical monographs. New York: Appleton. LCCN 31005951. OCLC 951855728 – via HathiTrust.

- 1 2 Félice, Fortuné Barthélemy de (1775). Encyclopédie, Ou Dictionnaire Universel Raisonné Des Connoissances Humaines. Vol. 3. Con–Impu – via Google Books.

- ↑ Bondeson, Jan (2004). The Two-Headed Boy, and Other Medical Marvels. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0801489587. OCLC 56642689.

- 1 2 Morand, S.F. (1748). "Histoire de l'Enfant de Joigny, qui a été treinte-un ans dans le ventre de sa mère; avec de remarques sur les phénoménes de cette espèce" [Story of the Child of Joigny, who was thirty-one years old in his mother's womb; with remarks on the phenomena of this species]. Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences (in French). Académie des Sciences. MDCCXLVIII: 108–122 – via Gallica (Bibliothèque Nationale de France).

- ↑ Bjerke, Ernst (13 December 2007). "Et "tiaarigt Svangerskab"" [A pregnancy of 10-years duration] (PDF). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen (in Norwegian). 127 (24): 3249–3253. PMID 18084382.

Citing Otto Christian Stengel's "Udfaldet af et tiaarigt Svangerskab" in Eyr, Vol. 2, 1827, pp. 134–37, et al.

- ↑ Bernard, Grace Parkhurst (1947). "Lithopedion from the Case of Dr. William H. H. Parkhurst, 1853". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (3): 377–378. JSTOR 44441156. PMID 20257377.

- ↑ Griffith, H. K. (September 1930). "A Case of Lithopædion". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 23 (11): 1542. ISSN 0035-9157. PMC 2182179. PMID 19987758.

- ↑ "Unusual case is treated by colored doctor". Yazoo Herald. Yazoo City, Mississippi. 13 October 1933. p. 1. Archived from the original on 12 November 1996. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

Dr. Miller states that he knew there was a growth of some kind in the stomach besides the tumor, and was much surprised after removing the tumor to discover a lithopaedion, a dead foetus (child) that had become petrified to the right of the tumor.

- ↑ Chase, A. L. (1968). "Lithopedion". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 99 (5): 226–30. PMC 1924357. PMID 5671128.

- ↑ Srisomboon, Jatupol; Maneewattana, Trong; Simarak, Suri; Koonlertkij, Sompong; Sirivatanapa, Pannee (March 1988). "Chronic abdominal pregnancy (Lithopedion): A case report". Chiang Mai Medical Journal. 27 (1): 45–52. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ↑ Chang, C M; Yu, K J; Lin, J J; Sheu, M H; Chang, C Y (1 June 2001). "Lithopedion". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi = Chinese Medical Journal; Free China ed. 64 (6): 369–372. ISSN 0578-1337. PMID 11534806.

- ↑ Frayer CA, Hibbert ML; Hibbert (July 1999). "Abdominal pregnancy in a 67-year-old woman undetected for 37 years. A case report". The Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 44 (7): 633–35. PMID 10442329.

- ↑ "Zahra Aboutalib – The 46 Year Pregnancy". RareHumans.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Rosenhek, Jackie (September 2008). "Fetal rock". Doctor's Review. Montreal: Parkhurst. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "The 46-Year Pregnancy". Extraordinary People. Season 3. Episode 1. 23 March 2005. 60 minutes in. Channel 5 (UK).

- ↑ Lachman, N; Satyapal, KS; Kalideen, JM; Moodley, TR (2001). "Lithopedion: a case report". Clinical Anatomy. 14 (1): 52–54. doi:10.1002/1098-2353(200101)14:1<52::AID-CA1009>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 11135399. S2CID 21390235.

- ↑ Kim, Mi Suk; Park, Soyoon; Lee, Tae Sung (April 2002). "Old abdominal pregnancy presenting as an ovarian neoplasm". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 17 (2): 274–75. doi:10.3346/jkms.2002.17.2.274. PMC 3054860. PMID 11961318.

- ↑ Burger, Natalie Z.; Hung, Y. Elizabeth; Kalof, Alexandra N.; Casson, Peter R. (May 2007). "Lithopedion: laparoscopic diagnosis and removal" (PDF). Fertility and Sterility. 87 (5): 1208–1209. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.11.065. PMID 17289039. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ Contreras, Claudia; López, Virgilio Cardona (2006). "Litopedión" (PDF). Revista Médica Hondureña (in Spanish). Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Colegio Médico de Honduras. 74 (3): 782. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- ↑ Ede, J; Sobnach, S; Castillo, F; Bhyat, A; Corbett, JH (August 2011). "The lithopedion – an unusual cause of an abdominal mass". South African Journal of Surgery. 49 (3): 140–41. PMID 21933501.

- ↑ Folley, Dr. Andrew (28 October 2011). "Stone baby". contemporaryobgyn.net. Archived from the original on 3 December 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ Cabrera, Angel Rafael Rodríguez; Hernández, Yanela Infante; Dávila, Carlos Manuel Hernández (21 June 2012). "Litopedion. Presentación de un caso". Medisur (in Spanish). 10 (3): 237–240. ISSN 1727-897X. Archived from the original on 9 February 2023. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ "35 year old 'stone baby' removed from 70 year old woman's womb". Siasat.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ Osayimwen, Etinosa (2 April 2013). "92-yr-old woman Miraculously delivers 'stone baby' after 60 yrs pregnancy". The Herald. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Nelson, Sara (12 December 2013). "Stone Baby: Doctors Find 40-Year-Old Lithopaedion Foetus in Body of Woman, 82". Huffington Post UK. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ↑ Smith, Lydia (12 February 2014). "Four Decades Old 'Stone Baby' Inside Brazilian Pensioner". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ "Chilean woman 'carried calcified foetus for 50 years'". BBC News. 20 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Buchanan, Rose Troup (26 August 2014). "36-year-old skeleton of dead baby found inside Indian woman". The Independent. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ↑ Atieno, Anyango (19 November 2020). "Woman gives birth to 13-year old stone baby". The Standard. Nairobi, Kenya. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

Further reading

- Costa, S. D.; Presley, J.; Bastert, G. (August 1991). "Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 46 (8): 515–525. doi:10.1097/00006254-199108000-00003. ISSN 0029-7828. PMID 1886705.

Believe this includes the archeological case in Costebelle, France mentioned in history section