A cellarette or cellaret is a small furniture cabinet, available in various sizes, shapes, and designs which is used to store bottles of alcoholic beverages such as wine or whiskey. They usually come with some type of security such as a lock to protect the contents. Such wooden containers for alcoholic beverages appeared in Europe as early as the fifteenth century. They first appeared in America in the early eighteenth century and were popular through the nineteenth century. They were usually made of a decorative wood and sometimes had special designs so as to conceal them from the casual observer. They were found in pubs, taverns, and homes of the wealthy.

History

Wood box containers as freestanding alcoholic beverage cabinets first appeared in Europe in the fifteenth century to hold and secure alcoholic beverages in public houses. Cellarettes first appeared in colonial America in the eighteenth century as a form of the European liquor cabinet. The main purpose of a liquor cabinet or cellarette was to secure wine and whiskey from theft as the bottles were hidden and the cabinet could have a lock.[1]

During the American Revolutionary War and the Civil War army officers' cellarettes often came with crystal decanters, shot glasses, pitchers, funnels, and drinking goblets.[1] Eighteenth century cellarette designs were used into the twentieth century. Cellarettes of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries were found in taverns and pubs and, in some cases, in the private homes of the elite.[2]

Prohibition in the United States brought about variations of trompe-l'œil cellarettes designed to conceal illegal alcoholic beverages. To the casual observer, the three dimensional trompe-l'œil artwork on these cellarettes made them appear to be an ordinary table, bookcase, or other piece of furniture.[1]

Description

Cellarettes in England and America were custom designed wooden chests to carry, transport and store small numbers of bottled alcoholic beverages. They were often made of fine decorative wood like mahogany, rosewood, or walnut and could be of various shapes and sizes. Cellarettes were generally associated with dining room furniture. Sometimes cellarettes were small portable pieces of furniture with handles that could be moved from room to room in a house. Another type was a permanent piece of furniture built on a stand with a sliding shelf to hold glasses and a drawer for serving paraphernalia.[3]

They could be free standing or built into a "pedestal-end" dining room buffet serving sideboard. Normally a cellarette had a hinged door or hinged top cover. Frequently a lock was provided, to secure the contents from thieves.[1] Some cellarettes were lined internally with metal. This allowed wine or food to be iced keeping them longer than if they were at room temperature.[3] The metal also prevented melted ice water from soaking into the wood.[4] Men of wealth had as many as three cellarettes at a time as a status symbol, not necessarily indicating one was a heavy drinker.[2]

In the late-18th and early-19th centuries, cellarettes were typically simple in design, following a Neoclassical aesthetic. Eventually, as Neoclassicism gave way to the more ostentatious Empire style, cellarettes became heavier and more ornate, emphasizing Roman and Grecian motifs. Some examples were made in the shape of sarcophagi mounted with lions' heads and animal-paw feet.[5] Cellarette use declined in the 20th century due to the use of the refrigerator.[6]

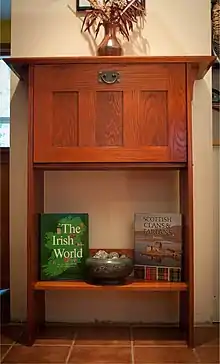

Mission style cellarette, built in 2007

Mission style cellarette, built in 2007 Cellarette at the de Young's International Arts & Crafts exhibition

Cellarette at the de Young's International Arts & Crafts exhibition Antique cellarette - "sarcophagus" style located at Lanier Mansion in Madison, Ind.

Antique cellarette - "sarcophagus" style located at Lanier Mansion in Madison, Ind. Sideboard, Cellarette, and Painting Cleveland Museum of Art - Gallery 205

Sideboard, Cellarette, and Painting Cleveland Museum of Art - Gallery 205

Etymology and term origin

When the word cellarette is broken apart as "cellar-ette" it denotes a small piece of furniture used to store bottles of alcoholic beverages. It is associated with a food serving sideboard used in a formal dining room area of a home.[7] Some sources say that the word "cellarette" came into use during the eighteenth century at the time of cabinetmaker George Hepplewhite. In Hepplewhite's 1794 The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide he demonstrates cellarettes as being octagonal and elliptical shaped with internal compartments for bottles of wine and liquor.[4] Renowned eighteenth century Charleston, South Carolina, furniture craftsman Thomas Elfe made several "Mahogany Cases for bottles with brass handles" for £12.[4] In 1803, furniture designer Thomas Sheraton described the piece as: "Cellaret, amongst cabinet makers, denotes a convenience for wine, or wine cistern.[4]

In the eighteenth century a cellarette was sometimes referred to as a "Mahogany Butler for liquors" or a "wine cooler" or a "butler".[4] The word bouteillier/butler was later standardized as a reference to the staff person exercising custodial responsibility over the bottles contained in a cellarette or wine cellar.[8][9]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Smith 2007, p. 359.

- 1 2 Howard 2007, p. 148.

- 1 2 Margon 1975, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burton 1997, p. 58.

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 604.

- ↑ "Cellarette". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ↑ Prown 2000, p. 48.

- ↑ Hanks 2003, p. 207.

- ↑ Jones 2017, p. 99.

General and cited references

- Burton, E. Milby (1997). Charleston Furniture, 1700-1825. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-147-2.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 604.

- Hanks, Patrick (2003). Dictionary of American Family Names. Oxforn University Press. ISBN 9780199771691.

- Howard, Hugh (2007). Houses of the Founding Fathers. Artisan. ISBN 978-1-57965-275-3.

- Jones, Paul Anthony (2017). The Accidental Dictionary. Pegasus Books. ISBN 9781681775852.

- Margon, Lester (1975). American Furniture Treasures. Dover Publications, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-486-23056-6.

- Prown, Jules David (2000). American artifacts. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87013-524-8.

- Smith, Andrew F. (2007). Oxford Companion to American Food & Drink. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530796-2.