| Lion Capital of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

Four Asiatic lions stand back to back on a circular abacus. The Buddhist wheel of the moral law appears in relief below each lion. Between the chakras appear four animals in profile—horse, bull, elephant, and lion. The architectural bell below the abacus, is a stylized upside-down lotus | |

| Material | Sandstone |

| Height | 2.1 metres (7 ft) |

| Width | 86 centimetres (34 in) (diameter of abacus) |

| Created | 3rd century BCE |

| Discovered | F. O. Oertel (excavator), 1904–1905 |

| Present location | Sarnath Museum, India |

| Registration | A 1 |

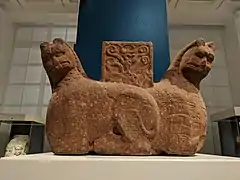

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the capital, or head, of a column erected by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in Sarnath, India, c. 250 BCE. Its crowning features[1] are four life-sized lions set back to back on a drum-shaped abacus. The side of the abacus is adorned with wheels in relief, and interspersing them, four animals, a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a galloping horse follow each other from right to left. A bell-shaped lotus forms the lowest member of the capital, and the whole 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall, carved out of a single block of sandstone and highly polished, was secured to its monolithic column by a metal dowel. Erected after Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, it commemorated the site of Gautama Buddha's first sermon some two centuries before.

The capital eventually fell to the ground and was buried. It was excavated by the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) in the very early years of the 20th century. The excavation was undertaken by F. O. Oertel in the ASI winter season of 1904–1905. The column, which had broken before it became buried, remains in its original location in Sarnath, protected but on view for visitors. The Lion Capital was in much better condition, though not undamaged. It was cracked across the neck just above the lotus, and two of its lions had sustained damage to their heads. It is displayed not far from the excavation site in the Sarnath Museum, the oldest site museum of the ASI.

The lion capital is among the first group of significant stone sculptures to have appeared in South Asia after the end of the Indus Valley Civilisation 1,600 years earlier. Their sudden appearance, as well as similarities to Persepolitan columns of Iran before the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BCE, have led some to conjecture an eastward migration of Iranian stonemasons among whom the tradition of naturalistic carving had been preserved during the intervening decades. Others have countered that a tradition of erecting columns in wood and copper had a history in India and the transition to stone was but a small step in an empire and period in which ideas and technologies were in a state of flux. The lion capital is rich in symbolism, both Buddhist and secular.

In July 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, the interim prime minister of India, proposed in the Constituent Assembly of India that the wheel on the abacus be the model for the wheel in the centre of the Dominion of India's new national flag, and the capital itself without the lotus the model for the state emblem. The proposal was accepted in December 1947.

History

Sarnath had a history of visits and some exploration in the 18th and 19th centuries. William Hodges, the painter visited in 1780 and made a record of the Dhamek Stupa, the most conspicuous monument at the site. In 1794, Jonathan Duncan, the Commissioner of Benares noted diggings for bricks carried out by Jagat Singh, the Dewan of the Raja of Benares. These had taken place 150 metres (490 ft) to the west of the Dhamekh.[2] Colin Mackenzie visited in 1815 and found some sculpture which he donated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In 1861 Alexander Cunningham attempted to dig down into the Dhamekh from its top to uncover relics.[2] He soon abandoned the effort, but not before noting that votive models of the stupa were scattered in the vicinity, lending credence to the view that the Dhamekh marked the spot at which the Buddha had preached his first sermon.[2]

For his investigations, Cunningham preferred to glean information from foreign sources. A French translation by Stanislas Julien of the travels of the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (then known as Hiuan-tsang) in India from 629 CE to 645 CE had appeared in 1857–1858.[3][4] In his account, Xuanzang mentioned a tall stupa to the northeast of Varanasi off the right bank of the Varuna river and a pillar nearby erected by Ashoka that was, "glistening and smooth as ice." He mentioned a monastery in "Mrigdeva", or Deer Park 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) away. Here there was another pillar erected by Ashoka about 21 metres (70 ft) high and shining "as bright as jade."[5] In the view of historian Frederick Asher, Xuanzang's account sometimes employed monuments as symbolic devices to fix miracles in a place.[6] More than two centuries before Xuanzang's visit, at the very beginning of the fifth century another Chinese visitor, Faxian, had recorded a short description of Sarnath. Faxian had also mentioned some towers, one at the site where the Buddha met the five disciples and another "60 paces north" where he gave the first sermon, the account being more about relating the traditional stories than giving particulars of geography.[4] Neither account was written on-site, but from memory upon returning to China.[6] Giving more literal credence to the accounts of Faxian and Xuanzang, the museum curator Sushma Jansari suggests that they could imply the existence of a greater number of Ashokan pillars during early historic[lower-alpha 1] South Asia and its immediate aftermath than had remained at the time of the 18th- and 19th-century British investigations.[8]

Although Buddhism and Buddhist monasticism had suffered setbacks in northwestern and southwestern India in the first millennium CE, they remained prominent in the religious life of central and northeastern regions well into the early centuries of the second millennium. This occurred despite Hindu and Jain religious establishments increasingly attracting the support of both the ordinary, non-clerical, public and royalty.[9] "In the historiography of India," according to archaeologist Lars Fogelin, "the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries are often depicted as a period when Islam was forcibly imposed on the native Hindu population. For British colonial historians, this depiction of Islamic despots served to illustrate the beneficence of British rule. Some postcolonial nationalist historians have used the presumed historical oppression of Hindus by Muslims to argue for a more Hindu, rather than secular, India. Buddhism has only a small place within these larger narratives of despotism, destruction, and desecration."[10]

According to historian Richard Eaton, instead of arbitrary attacks on Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples, the common practice of planning a conquest involved the swift and strictly defined desecration of those temples that were supported and frequented by royalty. The strategy was not new to India but had been prevalent there considerably before the arrival of the Ghaznavids and the Ghurids.[11] Temples had been the inevitable arenas for the struggle for kingly power.[12] The Turkish invaders followed the settled patterns.[12] Among Hindus and Jains, many temples have survived until the present day.[12] Whereas royal temples were raided and brought down, the ones attended by ordinary people were often left undisturbed.[12] "The same could have occurred with Buddhist institutions focused on the laity, had they existed." according to Fogelin, "However, by the thirteenth century CE, Buddhist monasteries in the Gangetic Plain and northeastern India were prominently supported by local and regional kings, and their relations with the non-elite laity consisted of little more than serving as landlords."[12] According to Eaton, "Detached from a Buddhist laity, these establishments had by this time become dependent on the patronage of local royal authorities, with whom they were identified."[13] Echoing the same theme, art historian Frederick Asher says, "Muhammad of Ghor, who did conquer Benares in 1193–94 ... might have plundered Sarnath, more likely for whatever wealth was imagined to be stored there ... than for the sake of iconoclastic destruction."[14]

Sarnath did not have unbroken history. Very few Buddhists remained in India after the 12th century. Buddhists from Tibet, Burma, and Southeast Asia did make pilgrimages to South Asia from the 13th to the 17th centuries, but their most common destination was Bodhgaya, the site of the Buddha's enlightenment, not Sarnath the site of his first sermon and the birthplace of the Buddhist order.[15] Sarnath was pillaged again in 1894 when a large number of bricks were carried away for use as ballast in a nearby railway line.[2]

Excavation and display

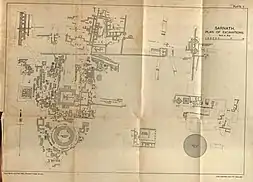

When F. O. Oertel, an engineer in the Public Works Department, who had surveyed Hindu and Buddhist sites in Burma and Central India in the 1890s[16] was appointed superintending engineer at Varanasi, he constructed a storehouse at Sarnath for the artefacts found earlier and paved the road to Sarnath. He then convinced Sir John Marshall, the director-general of the ASI, to be allowed to excavate Sarnath in the winter of 1904–05.[17] John Marshall resolved to put in place plans for a museum to keep the excavated artefacts close to the site.[18]

Oertel began his excavations in the vicinity of the Jagat Singh stupa, which lies to the southwest of the Dhamek. He proceeded to the Main Shrine, north of the stupa. It was to the west of this shrine that he found the buried stump and fragments of the Ashokan pillar at Sarnath, and soon its lion capital.[19]

The Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath, now Archaeological Museum Sarnath, the first site museum of the ASI, was completed in 1910.[18] The lion capital has been displayed in the museum since.[18] Daya Ram Sahni, Assistant Superintendent of the ASI, and later its Director-General, supervised the organisation and labelling of the museum's collection and in 1914 completed the Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath".[18] Oertel's detailed report, "Excavations at Särnäth", had appeared in 1908 in the Archæological Survey of India, Annual Report, 1904–5.[20]

Description

The capital is 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall in total. Its lowest portion is an inverted lotus petal bell[22] which is 61 centimetres (2 ft) high, carved in the Persepolitan style,[23] and decorated with 16 petals. The bell has been interpreted to be a stylized lotus, a common motif.[24] Above the bell is a circular abacus, or a drum-shaped slab, of diameter 86 centimetres (34 in) and height 34 centimetres (13+1⁄2 in). Set addorsed, on the abacus are four lions.[25] In this context, it means that only the frontal figures are visible joined at the shoulders, each with its back to another so as to form a pair and two pairs are perpendicular.[26] The lions are each 1.1 metres (3+3⁄4 ft) tall and have been described as "life-sized."[27]

Oertel describes the lions to be "standing back-to-back" in his original report of 1908.[28] Other authors have used the same expression in describing the lions' attitude, including in a 2014 study[29] and a 2017 review,[30] or have quoted Oertel using it, in a 2020 study.[31] The archaeologist Kazim Abdullaev, who analysed the pose of the Sarnath lions in a 2014 study, concluded they were seated on account of their backs sloping more steeply upwards than those of standing lions.[32] They have been described as seated in some other studies.[26][33][34]

Two lions were undamaged. The heads of the other two had come off before being buried and upon excavation required affixing. Of these damaged, one lion was missing the lower jaw at the time of the initial excavation and the other the upper, both not found since. On the side of the abacus and below each lion is carved a wheel of 24 spokes in high relief. Between the wheels, also shown in high relief are four animals following each other from right to left. They are a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a horse; the first three are shown at walking pace but the horse is at full gallop.[35][28] The capital which was carved from a single block of marble is broken across the necking just above the bell.

The capital has a polished finish.[33] Although most sandstone is difficult to polish without dislodging the grains on the surface, according to a 2020 study by Frederick Asher, very fine-grained sandstone found, e.g. in Chunar, can be polished with a fine abrasive or even patiently with wood.[37] According to art historian Gail Maxwell, the sandstone received its shine through the application of heat which gives a lasting glass-like finish to the stone.[22] The pillar which bore the capital aloft "remains broken in several pieces at the site and is now protected by a glass enclosure that separates the pillar from visitors."[21] Before it fell, it is thought the capital was secured to the intact pillar by a metal dowel.

The lions supported a larger wheel,[22] also polished, symbolizing the dharmachakra, the Buddhist wheel of the "social order and the sacred law,"[38] which is lost except for fragments.[lower-alpha 2] [40] It was held in place by a shaft. According to the detailed[41] Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath, 1914, written by Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India, 1931–1935, the stone shaft was not found but, "its thickness can be estimated from the mortice hole, 20 centimetres (8 in) in diameter, drilled into the stone between the lions' heads."[42] Further, according to Sahni, "Of the wheel itself, four small fragments were found. The ends of thirteen spokes remain on these pieces. Their total number was presumably thirty-two."[42] The original diameter of the surmounting wheel was conjectured to have been 0.84 metres (2+3⁄4 ft).[28] The wheel fragments are on display in the Sarnath Museum.[lower-alpha 3]

According to the museum's Catalogue, the lions did not have eyeballs; instead, precious stones were initially placed in the eye sockets. The stones were held in place by iron pins passing through fine holes in the upper and lower lids. Although the stones were lost, one pin had remained embedded in the upper left lid of one of the lions at the time of the discovery.[35]

Symbolism

The first of the existing visual portrayals of lions in South Asia are the Maurya columns such as the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath.[44] Some scholars believe that lions were introduced into India from western Asia as a quarry for royal hunts, implying that they became a feral population thereafter and eventually became wild.[44][lower-alpha 4] This is suggested to have resulted from the contact of the South Asian dynasties with the Achaemenid and Seleucid empires when hunting lions became a sign of royal prowess.[44] The Achaemenids had inherited the pastime from western Asia. There is evidence from Syria of lion hunts and lion menageries with caged lions in the early fourth-millennium BCE.[44] When emperor Ashoka converted to Buddhism in the wake of large-scale killing and destruction by his army in Kalinga, or what is today Odisha in eastern India, he gave a new direction to the imaginative treatment of the lion: from being a symbolic object of royal domination, the lion became an emblem of royal prowess.[44] According to architectural historian Pushkar Sohoni, "In early Buddhist architecture, the lion, along with the horse, the elephant, and the zebu, were considered auspicious. All these animals appeared as a standard quartet on many Mauryan pillars."[44]

The lion capital and its Ashokan pillar have complex meanings. The lions—the four sitting addorsed on the abacus and the one badly damaged appearing in relief on its rim—have been associated with the Buddha, one of whose names was Shakyasimha, the lion of the Shakya clan.[45] The three other animals on the rim of the abacus have been associated with events in the life of Prince Siddhartha: the elephant with his mother Queen Maya's dream about his birth; the horse with Kanthaka, the mount of his departure from the palace in the dead of night, and the bull with his first meditation under the rose apple tree (jambu, syzygium aqueum).[45] The abacus and its animals have been related to Lake Anavatapta of a contemporary 3rd century BCE myth.[45] A water spout arose from the heart of this lake. After surfacing and splitting into four streams it emanated from the mouths of the same four animals sitting on the lake's shore and flowed onto the four corners of the earth, like the message of the Buddha or of Ashoka himself.[45] The pillar, thus, has been likened both to the water spout rising to meet the lake-like abacus and also the axis mundi, the world's axis.[45]

The four lions have also been thought to be the cardinal directions as if roaring the Buddha's message to the remotest parts.[33] A later Buddhist text, the Maha-Sihanada Sutta (Great Discourse on the Lions' Roar), pointedly links the wheel and lion with its refrain, "[the Buddha] roars his lion’s roar in the assemblies, and sets rolling the Wheel of Dharma [wheel of the true eternal law]."[48] In other interpretations, the four small animals shown on the side of the abacus have been thought to represent the cardinal directions: the lion (north), elephant (west), bull (south), and horse (east),[49] and the smaller wheels for the solstices and the equinoxes.[50] According to Raymond Allchin, " The abacus depicts four Dharmacakras facing the four quarters, interspersed by four noble beasts, who in early Buddhist texts represent the four quarters."[33] In the Aṅguttara Nikāya, the Buddha compared himself to the Indian lotus, a flower that rises clean and pure from muddy pond water, as he rose above an impure world to achieve awakening.[50] According to art historian Gail Maxwell, The lions are fashioned so as to affect the viewer by the use of shape, colour, and texture, not necessarily to represent reality, suggestive of the addorsed capitals of the Achaemenid Empire. But all other aspects are Indian.[22] "The four lions," according to her, "very likely signify "the sovereignty of both Ashoka, since the pillar was erected near the capital of his kingdom and of the truths taught by the Buddha, whose clan, the Shakyas, used the lion as their emblem."[22]

Scholars have debated the meanings of the wheels, the large one that had once surmounted the capital and the four appearing in relief along the rim of the abacus. Some have likened the wheels, especially the lost larger one, to the Buddhist wheel of the moral law, the dharmachakra, which the Buddha began to turn in Sarnath and whose motion through time and space has spread his message universally.[48][51] Others have thought them to have been nonsectarian symbols, promoting an ethical notion of rulership, or chakravartin (literally wheel turner) which Ashoka might have been aspiring to present himself,[48] to align himself with the prestige and universality of the Buddha.[45][48] According to cultural historian Vasudeva Sharan Agrawala, the dharmachakra represented the body of the Buddha and the lions the throne. In his view, the Sarnath capital is equally Vedic and Buddhist in the significance of its various parts.[52] According to the Indologist John Irwin, the wheels on the rim of the abacus do not represent the Buddhist wheels of the sacred law but chariot wheels of the period which typically had 24 spokes.[53] According to the anthropologist Lars Fogelin, as the only capital to exhibit wheel motifs, the lion capital at Sarnath is thought to symbolize the wheel of the moral law in "a specifically Buddhist sense of the term." Overall, the symbolism of the Sarnath column and capital is thought to be more Buddhist than secular.[54]

According to cultural historian and museologist Sudeshna Guha, the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy argued in 1935 that Buddhist symbolism was not the only one established in the Vedic period which had preceded Buddhism and during which worship did not have a visual representation. The dharmachakra chiefly stood in Coomaraswamy's words for "the Revolution of the year, as Father Time, the flowing tide of all begotten things, dependent on the Sun.”[55] According to Guha, "Coomaraswamy’s interpretations aided the placing of the 'Sarnath wheel,' found broken and not physically connected with the lions on the pillar during Oertel’s excavations, on the Indian national flag."[55] Guha adds, "The historian and superintendent of the Museums Branch of the Archaeological Survey of India (1946–51), V. S. Agrawala, who was in charge of making the plaster cast in 1946, followed him in extending its meaning as the chakra dhvaja or 'the wheel flag.' Without invoking any new evidence Agrawala laboured to explain that 'there is no cult allegiance here in the symbolism of the Mahachakra [‘great wheel’] and its accessories like the four lions . . . here one is face to face with an acclamation to the single unmanifested and undifferentiated divine phenomenon.'"[55][56]

The significance and meaning of the lotus bell, the lowest member of the capital, has also been discussed in the literature. Agrawala explained in 1964: "The first decorative element of the Lion Capital can by no means be interpreted as Indo-Persepolitan Bell. It is in every respect the Purna-ghata motif of ancient Indian art and religion, overflowing with luxuriant lotus petals."[57] Writing in 1975, the Indologist John Irwin asked, "Did the carvers of 'Aśokan' pillars derive the idea of their bell from Persepolis, or not?" Irwin added, "So far, only one scholar, the late A. K. Coomaraswamy, has argued in the negative. He alone tried to prove that Indian artists had arrived independently at their form of bell. The logic of his argument, however, was weak."[58] According to Irwin, Coomaraswamy had picked some "untypical" details of reliefs of a century later in which the lotus had been stylized to argue that "the petals, stamen and pericarp of the lotus flower as stylized ... must have inspired the rope-moulding and abacus respectively of the Asokan pillar-capital. This argument is too weak to convince anybody but the already converted."[58] According to Irwin, "V. S. Agrawala followed Coomaraswamy in refusing to accept the 'Asokan bell' as anything but Indian, but he presented his case as an article of faith, making no attempt to prove it. He saw the bell as an inverted lotus flower 'overflowing' the form of a symbolic vase-of-plenty (purna-ghata)."[58]

Influences

Writing in 1911—following two decades of investigations—the historian Vincent Smith concluded that all the pillars that were considered Ashokan had been erected by the orders of emperor Ashoka during the twenty-five-year period from 257 BCE to 232 BCE. Setting the stage for future debate he suggested that their execution was "essentially foreign."[59] Following up in 1922, John Marshall was the first scholar to suggest that the Sarnath capital was the work of foreign artisans working in India. Comparing the capital to a male figure from Parkham, Marshall wrote, "While the Sārnāth capital is thus an exotic, alien to Indian ideas in expression and in execution, the statue of Pārkham falls naturally into line with other products of indigenous art and affords a valuable starting point for the study of its evolution."[60] The realism of the lions, the straining tendons of their paws, and the "flesh around the jaws" have led others to ask about the provenance of some of the art commonly ascribed to the Maurya period.[45]

Expanding on the theme further Vincent Smith wrote in 1930 that the shine of the Mauryan pillars, the lotus bell bases of their capitals and the stylized lions, suggested Iranian carvers had migrated to the Mauryan empire after Alexander the Great's sacking of Persepolis in 330 BCE. He and others after him have detected Persian-Hellenistic influences in Mauryan art.[61] The subject was taken up by Mortimer Wheeler who added that until the advent of the Mauryas Indian art had not strayed beyond the confines of folk art, and on that basis speculated that two or three generations after the downfall of the Achaemenid empire Hellenistic craftsmen working in Persepolis had been hired by emperor Ashoka.[59] Wheeler did suggest that free-standing pillars had not appeared in Europe before the advent of the Roman empire.[59]

Others who made noteworthy contributions were the linguist and Buddhism scholar Jean Przyluski, art historian Benjamin Rowland, and cultural historian and Sanskritist Vasudeva S. Agrawala, but rather than the archaeology or history, they concentrated on the symbolism which they thought was given concrete form by features of pre-Buddhist metaphysics.[62]

In 1973, John Irwin challenged the assertions of foreign influence by advancing three hypotheses: (a) Not all pillars were made for Ashoka; some had been adapted for his use; (b) whereas the four lions did seem to have Persian influence, the spiritedness of bull and the elephant betray an intimate familiarity with animals whose habitat did not extend to Iran; and (c) Ashoka had channelled a preexisting industry and culture devoted to treating a pillar as a symbol for axis mundi, the axis around which the earth revolves.[61] Irwin acknowledged the existence of numerous precedents of pillars with animal effigies in the ancient world, from the djed-pillars of Pre-dynastic Egypt, to the Sphinx of the Naxians, but argued that Greek examples were in essence classical load-bearing pillars with an animal on top, whereas the Indian pillars of Ashoka were more slender, and closer to monumental stone-versions of dhvajas, portable wooden standards known in India from undetermined antiquity.[63] To J. C. Harle, the Sarnath lions did show a conventionalized style associated with Achaemenid or Sargonid empires, but the floral motifs on the Mauryan abaci show the influence of western Asian traditions older than any in the Hellenistic world.[64] He also echoed Irwin's idea that as there are no examples elsewhere of "single, free-standing" pillars, they must be the product of a South Asian tradition, perhaps in non-durable materials such as wood for the pillar and copper for the crown.[64]

Irwin's first hypothesis has been challenged by Frederick Asher who says, "That the pillars attributed to Aśoka are really from his time is a virtual certainty despite arguments that they date earlier (Irwin 973). The author of the pillars’ inscriptions, Piyadasi, is known to be Aśoka from the Maski inscription in present-day Karnataka. Moreover, the symbolism of the pillars and their capitals, appropriate for these royal edicts, suggests that the pillars were made to carry the inscriptions."[65]

Osmund Bopearachchi has mentioned Irwin and V. S. Agrawala among those who have held that the early stone carving was the work of Indians alone. He has suggested that the inspiration for them and the technique of polishing them came from Persia, noting further the absence of any archaeological evidence for Agrawala's claim that the technique went back to the Vedic Age and was inherited by the Mauryans.[66]

Upinder Singh has observed that the cultural standing of the Asiatic lion (Panthera leo Persica, also Persian lion) as a symbol of projecting political power had significantly increased in India after the rise of the Mahajanapadas in the second half of the first millennium BCE. By Ashoka's time, the Asiatic lion had a long history of being employed as a symbol of the Achaemenian royalty. As the monarch of a vast realm, but also a Buddhist, he sought new symbols to project his power. Thus whereas the Ashokan lions seemed remarkably similar to the conventionalized Persian, the idea of using a pair of addorsed lions to project both spiritual and temporal power was new.[67]

Christopher Ernest Tadgell considers it unlikely that Ashoka's capital was carved "without the experience imported by Persian immigrants," but suggests that regardless of Ashoka's purpose of using Buddhism as a unifying force, his success depended on the prevailing worship of the pole (stambha) as the axis mundi in the native pre-Buddhist shrines.[68]

Harry Falk, while categorically stating a Mauryan debt to "the stonework inherited from Achaemenid Iran," of the appearance during the Mauryan period of artwork that contrasted remarkably with local styles, and stating the likelihood of traditions of producing "naturalistic forms" being preserved in Iranian stonemasons for the critical decades between the fall of Persepolis and the appearance of Mauryan columns, emphasises the entrepreneurial spirit of Ashoka who, "did not shrink from doing what only the most illustrious rulers outside India had done before him: he had pillars produced of unbelievable dimensions, cut in one piece and transported to predefined places—pillars crowned with lions and bulls of an unprecedented naturalistic beauty."[69]

Frederick Asher, summarizing, credits the world system that had briefly emerged during Ashoka's rule. In his view, South Asia had a hitherto unprecedented level of engagement with the Mediterranean world during the Mauryan period. It is no coincidence that it is during that period stone sculpture appeared in South Asia, at least in the form associated with Ashokan columns. But this should not be seen in colonialist terms as an export from an Achaemenian or Hellenistic centre to the South Asian periphery but as the result of Ashoka's entrepreneurial engagement with the larger world.[70] The culture in India was more receptive to innovation and there was a sense of a common culture, caused partly by the expansion of Buddhism to the borders with Iran, and the appearance of markers proclaiming a message. When the Ashokan empire fell, the breakdown was drastic. New styles of art emerged, but their artistic inspirations and appeal were more local.[70]

Author and editor Richard Stoneman arguing more generally about sculpture in early historic South Asia suggests that in figural and decorative sculpture, style and content need to be considered separately. "Techniques of carving," he states, "are not the same as the choice of subject matter, and choices of decorative detail lie somewhere between. Copying is not the only model: interaction and creative re-use may be more rewarding concepts." He describes the differing interpretations by art historians John Boardman and Margaret Cool Root of the extent of Greek influence on the art of Persepolis. Whereas Boardman sees "similarities, and probably influence, in technique and style," Root discounts influence "on the basis of pictorial content and ideological infrastructure; and both seem to be right."[71]

A transmission of Hellentistic architectural and decorative features from the Seleucid cities of Central Asia, or the Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum were posited by Boardman,[72] who stated, "The Sarnath lions take the same forms a little farther, but again the realistic carving of the flews, the crinkled folds beside the mouth, is not a feature of Persian or eastern work at all, but a reflection of the realistic rendering of this feature by Hellenistic Greek artists, who could effectively reduce the force of the compact eastern forms by such treatment. It remains odd that Panthera leo persica, whose distinctive belly hair (unlike the African lion) was carefully depicted by Mesopotamian artists, whence by Greek and then Persian, should lack this feature here; indeed the Sarnath lions and their kin owe all to the arts of others rather than native observation."[73] Sounding a similar theme as Asher, he concludes that it was "all a matter of assimilation and sometimes reinterpretation, rather than a crude choice between indigenous or foreign. But the visual experience of many Ashokan and later city dwellers in India was considerably conditioned by foreign arts, translated to an Indian environment, just as the archaic Greek had been by the Syrian, the Roman by the Greek, and the Persian by the arts of their whole empire."[74]

To Alexander Cunningham in Sanchi in 1851, the addorsed lions in the gateways and especially their claws bore the signs of Greek influence. "Many of the details," continues Stonemen, "such as the manes, do remind one strongly of Greek styles of carving." Citing art historian Sheila Huntington, Stoneman describes the Asiatic lion primarily to be a West Asiatic animal, and elephants and bulls to be the more characteristic beasts of India. "There is, then, the evidence here," he concludes, "for detailing influenced by Greek art, often through Persian models, in the architecture of the third to second centuries BCE. Sir John Marshall, after drawing attention to such foreign motifs at Sanchi as the ‘Assyrian tree of life, the West Asiatic winged beasts, and grapes, went on to remark that ‘nothing in these carvings is really mimetic, nothing certainly which degrades their art to the rank of a servile school’."[75]

Legacy

A stamp issued by the Dominion of India of its new national flag on 15 August 1947. In its centre is a wheel of 24 spokes based on those appearing on the side of the abacus in Ashoka's capital.

A stamp issued by the Dominion of India of its new national flag on 15 August 1947. In its centre is a wheel of 24 spokes based on those appearing on the side of the abacus in Ashoka's capital. "India in Flanders Field, 2011." Ypres, Belgium. Standing 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) tall, the memorial introduces many visitors to the 130,000 lives lost by Indian Expeditionary Force in this region in the First World War.[76]

"India in Flanders Field, 2011." Ypres, Belgium. Standing 1.8 metres (5.9 ft) tall, the memorial introduces many visitors to the 130,000 lives lost by Indian Expeditionary Force in this region in the First World War.[76]

In the days leading to India's independence, the Sarnath capital played an important role in the creation of both the state emblem and the national flag of the Dominion of India.[77][78] They were modelled on the lions and the dharmachakra of the capital, and their adoption constituted an attempt to give India a symbolism of ethical sovereignty.[77][79] On 22 July 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, the interim prime minister of India, and later the prime minister of the Republic of India proposed formally in the Constituent Assembly of India, which was tasked with creating the Constitution of India:[77]

Resolved that the National Flag of India shall be a horizontal tricolour of deep saffron (kesari), white and dark green in equal proportion. In the centre of the white band, there shall be a Wheel in navy blue to represent the Charkha. The design of the Wheel shall be that of the Wheel (Chakra) which appears on the abacus of the Sarnath Lion Capital of Asoka. The diameter of the Wheel shall approximate to the width of the white band. The ratio of the width to the length of the flag shall ordinarily be 2:3.[77]

Although several members in the assembly had proposed other meanings for India's national symbols, Nehru's meaning came to prevail.[77] On 11 December 1947, the Constituent Assembly adopted the resolution.[77] Nehru was well-acquainted with the history of Ashoka, having written about it in his books Letters from a father to his daughter and The Discovery of India.[77] The major contemporary philosopher of the religions of India, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, also advised Nehru in the choice.[77] The state emblem of the Dominion of India was accepted by the cabinet on 29 December 1947, with the resolution of a national motto set aside for a future date.[80] Nehru also explicitly displaced the spinning wheel, the charkha, at the centre of the flag of the Indian National Congress,[lower-alpha 7] the main instrument of Indian nationalism.[lower-alpha 8] He also attempted to give the dharmachakra the meaning of peace and internationalism which in his view had prevailed in Ashoka's empire at the time of the erection of the pillars.[lower-alpha 9]

The imaginative treatment of the lion changed in other ways after emperor Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism and the raising of the lion capital. Not just a symbol of imperial strength or the Buddha's power, the lion became also a symbol of peace.[76] Ashoka's lion capital has been used in memorials on battlefields. In the Ypres landscape, according to historian Karen Shelby, "the Indian Forces Memorial is the most striking. Through what would be unusual imagery for western eyes, the sculpture asserts an Indian presence. Eschewing traditional western figurative forms of commemoration, the statue is a replication of one of the Asokan lion capitals. ... The connections between the symbols of the lion capital and the postwar peaceful rhetoric are striking. Asoka’s acceptance of Buddhism was the result of witnessing the devastation after the successful Battle of Kalinga (261 B.C.E.). Affected by the bloodshed, he was filled with remorse and resolved to pursue a non-violent and peaceful approach to life. The latter symbolism is a fitting one in this context as Ypres ("leper" in Flemish) is also known as a 'city of peace'."[76]

Reconstructions

Various reconstructions of the Sarnath pillar and its capital have been proposed. The topmost wheel can rest on the backs of the four lions,[82] or it can be positioned higher (the exact length of the shaft supporting the wheel being unknown).[53] The full pillar is generally reconstructed straightforwardly from its archaeological remains, with the tall column supporting the capital, and the larger wheel on top.[53]

Related sculpture

Over the centuries, the lion capital of Ashoka served as an important artistic model, and inspired many creations throughout India and beyond:[88][89]

Lion capital of Ashoka at Sanchi with similar four addorsed lions, but with a flatter abacus showing alternating geese and flame palmettes, ca 250 BCE[90]

Lion capital of Ashoka at Sanchi with similar four addorsed lions, but with a flatter abacus showing alternating geese and flame palmettes, ca 250 BCE[90] Sanchi gateway relief, Satavahana period, 1st century BCE

Sanchi gateway relief, Satavahana period, 1st century BCE Sanchi gateway lion capital, 1st century BCE

Sanchi gateway lion capital, 1st century BCE

Mathura lion capital with an abacus (1st century CE)

Mathura lion capital with an abacus (1st century CE) Sanchi gateway relief showing a possible depiction of the Sarnath pillar, Satavahana period, 1st century CE.[91]

Sanchi gateway relief showing a possible depiction of the Sarnath pillar, Satavahana period, 1st century CE.[91] Lion Capital with mounting abacus atop, Old Termez, Uzbekistan, 1st century CE.[92]

Lion Capital with mounting abacus atop, Old Termez, Uzbekistan, 1st century CE.[92]

Kushan Empire lion capital, Khokhrakot, Haryana, 2nd century CE

Kushan Empire lion capital, Khokhrakot, Haryana, 2nd century CE A lion capital from Udayagiri Caves, early 5th century CE. Gupta period. Gwalior Fort Archaeological Museum.[93]

A lion capital from Udayagiri Caves, early 5th century CE. Gupta period. Gwalior Fort Archaeological Museum.[93] Lion capital from Sanchi, with remains of a surmounting wheel, circa 600 CE (Later Guptas period).[94][95]

Lion capital from Sanchi, with remains of a surmounting wheel, circa 600 CE (Later Guptas period).[94][95]

Notes

- ↑ "The decline of the Indus valley culture (c.2600–1900 BC) also meant the end of the Indian subcontinent’s ‘first urbanisation’. After a gap of more than a thousand years, archaeological excavations and textual evidence points to the re-emergence of cities, as well as widespread road and river-based trade networks connecting cities and other sites, in South Asia during the mid-first millennium BC. This phenomenon is referred to as the ‘second urbanisation’ and the period, c. 3rd century BC – 4th century AD, is known as the Early Historic."[7]

- ↑ "The famous four lion capital at Sarnath was surmounted by a wheel and stood above a carved abacus depicting the four noble, or cardinal, beasts – the lion, the elephant, the horse and the bull."[39]

- ↑ "The pillar was originally crowned by a large chakra, or wheel of truth, some of whose spokes are in the Sarnath Museum.[43]

- ↑ According to Wendy Doniger, the three deities Vishnu, Shiva, and Durga, "also have domesticated animals associated with them: the cow, the bull, and the buffalo, respectively. Thus the lion, when paired with any of these three animals, represents 'the feral god with the bovine servant'."[44]

- ↑ "Along with the bull, the elephant and lion are ubiquitous sacred symbols ... in the Buddha's birth narrative his mother Queen Maya, dreamed of a white elephant that entered her womb."[46]

- ↑ "The elephant was ... an important signifier in Buddhism. According to the story of the Buddha’s birth, his mother dreamed of a white elephant entering her womb through her side. The elephant eventually became a symbol for the Buddha himself.[47]

- ↑ "Nehru had moved for the chakra to replace M. K. Gandhi’s charkha (spinning wheel), which had been featured on previous flags."[79]

- ↑ "The organization that led India to independence, the Indian National Congress, was established in 1885."[81]

- ↑ "the Asokan period in Indian history was essentially an international period. ... It was not a narrowly national period . . . when India’s ambassadors went abroad to far countries and went abroad not in the way of an empire and imperialism but as ambassadors of peace and culture and goodwill." Jawaharlal Nehru quoted in [78]

References

- ↑ Harle 1994, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Ray 2014, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Fennet, Annick (2021). "The original 'failure'? A century of French archaeology in Afghan Bactria". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek worlds. The Routledge World Series. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 142–170, 144. ISBN 978-1-138-09069-9. LCCN 2020022295.

- 1 2 Asher 2020, p. 21.

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 44.

- 1 2 Asher 2020, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Jansari 2021, p. 43.

- ↑ Jansari 2021, pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Fogelin 2015, p. 220.

- ↑ Fogelin 2015, pp. 220–221.

- ↑ Eaton 2000, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fogelin 2015, p. 222–223.

- ↑ Eaton 2000, p. 297.

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 31.

- ↑ Asher 2020, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Guha 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Asher 2020, pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 3 4 Asher 2020, p. 35.

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 30.

- ↑ Oertel 1908.

- 1 2 Asher 2020, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Maxwell 2004, p. 362.

- ↑ Oertel 1908, p. 69 Quote: "The upper part of the capital is supported by an elegantly shaped Persepolitan bell-shaped member."

- ↑ Asher 2011, p. 433.

- ↑ Asher 2011, p. 425.

- 1 2 Vajpeyi 2012, p. 186.

- ↑ Dolan 2021, pp. 109–110.

- 1 2 3 Oertel 1908, p. 69.

- ↑ Ray 2014, p. 130.

- ↑ Greary, David; Mukherjee, Sraman (2017). "Buddhism in Contemporary India". In Jerryson, Michael K. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Buddhism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 36–60, 46. ISBN 9780199362387. LCCN 2016021264.

- ↑ Asif 2020, p. 41.

- ↑ Abdullaev 2014, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 Allchin 1995, p. 254.

- ↑ Singh 2017, p. 390.

- 1 2 Sahni 1914, p. 28.

- ↑ Huntington 1990, p. 90.

- ↑ Asher 2020, pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Allchin 1995, pp. 87, 254.

- ↑ Coningham & Young 2015, p. 444.

- ↑ Irwin 1990, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 35 Quote: "Although Marshall says explicitly little about his intention to give his Indian colleagues an active role in unearthing and presenting their own history, his actions clearly showed that he did. First among those whose work he promoted was Daya Ram Sahni, a Sanskritist by training who had worked on the excavations at Kushinagar in 1905, then Rajgir and Rampurva in 1906 and 1907. In an effort to keep material excavated at Sarnath close to the site, Marshall laid plans in 1904 to establish the Archaeological Museum Sarnath, the first site museum under the ASI; the building was completed in 1910. Although Sahni did not have a role in the Sarnath excavations, he was the one who supervised the work of arranging and labeling the museum’s holdings, and just four years later he published the lengthy and meticulously detailed Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath. Almost immediately after he began to work on the museum’s collections, he presented the site itself in his Guide to the Buddhist Ruins of Sarnath, probably the most frequently reprinted volume published by the ASI. Sahni became the first Indian director-general of the Survey in 1931."

- 1 2 Sahni 1914, p. 29.

- ↑ Wriggins 2021

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sohoni 2017, pp. 225–226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Asher 2020, p. 75.

- ↑ Pal 2016, p. 23.

- ↑ Sohoni 2017, p. 227.

- 1 2 3 4 Asher 2011, p. 432.

- ↑ Pabón-Charneco 2021, pp. 255–256.

- 1 2 Dolan 2021, p. 111.

- ↑ Dolan 2021, p. 110.

- ↑ Agrawala 1964a, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Irwin 1975, p. 643.

- ↑ Fogelin 2015, pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 3 Guha 2021, p. 62.

- ↑ Agrawala 1964b, p. 6.

- ↑ Agrawala 1964b, p. iii.

- 1 2 3 Irwin 1975, pp. 636–638.

- 1 2 3 Irwin 1973, p. 713.

- ↑ Asher 2006, p. 55.

- 1 2 Mitter 2001, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Irwin 1973, p. 714.

- ↑ Irwin 1974, p. 712-715.

- 1 2 Harle 1994, p. 24.

- ↑ Asher 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ Bopearachchi 2021, p. 25.

- ↑ Singh 2017, p. 391.

- ↑ Tadgell 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ Falk 2006, p. 154–155.

- 1 2 Asher 2006, p. 64.

- ↑ Stoneman 2019, p. 432.

- ↑ Boardman 1998, p. 15.

- ↑ Boardman 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Boardman 1998, p. 21.

- ↑ Stoneman 2019, p. 444.

- 1 2 3 Shelby 2021, p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Vajpeyi 2012, pp. 188–189.

- 1 2 Coningham & Young 2015, p. 465.

- 1 2 Asif 2020, p. 31.

- ↑ Ministry of Home Affairs (29 December 1947), Press Communique (PDF), Press Information Bureau, Government of India, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2017

- ↑ Kopstein, Jeffrey; Lichbach, Mark; Hanson, Stephen E. (2014), Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order, Cambridge University Press, p. 344, ISBN 978-1-139-99138-4, archived from the original on 21 August 2023, retrieved 21 July 2022

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 75, Even more pointedly referring to the Buddha's sermon, is the large stone wheel whose rim was supported on the backs of the four addorsed lions.

- 1 2 Irwin 1975, p. 743.

- ↑ Agrawala, Vasudeva (1965). Studies In Indian Art. Varanasi: Vishwavidyalaya Prakashan. p. 67.

- ↑ Agrawala 1964b, p. 123 (Fig. 6-7)

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 76.

- ↑ Tömory 1982, p. 21.

- ↑ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (31 August 2017). Archaeology and Buddhism in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-351-39432-1.

- ↑ Wheeler, Mortimer (1959). Early India and Pakistan: To Ashoka. Thames and Hudson, London. p. 175. Archived from the original on 25 August 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ↑ Asher 2020, p. 73.

- ↑ Ray, Himanshu Prabha (31 August 2017). Archaeology and Buddhism in South Asia. Taylor & Francis. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-351-39432-1. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

Worship of the Ashokan pillar, as shown at Stupa 3, Sanchi

- ↑ Abdullaev 2014, pp. 170–171 A capital with protomes of four lions from Old Termez This capital takes the form of four lion protomes, facing in different directions (the cardinal points) (Fig. 15, 15:a). In its artistic style, and especially in the treatment of the long wavy ringlets of the lions’ manes, it is comparable to some examples of Hellenistic sculpture. All the evidence indicates that it belonged to a stambha pillar and was not an ordinary capital. It would seem to be appropriate to a Greco-Buddhist figurative complex. ... As far as its function is concerned, we have one small indication in the form of a detail modeled on the backs of the lions. This is a fairly tall, square abacus, with two parallel relief lines running round the bottom. In the top of the abacus there is a square slot measuring 13-15×13-15 cm, into which another detail evidently was to be fitted. This detail may have been a beam, but is more likely to have been a symbol in the form of the wheel of the doctrine (Dharmachakra).53 This latter theory is supported by the fact that the backs of the lions’ necks are higher than the level of the abacuses, which would have complicated the fitting of beams. By contrast, a separate symbol – in this case a wheel – could have been quite easily fixed in the slot with the help of some projecting element; another way of it fastening it would have been with a metal bolt.

- ↑ Agrawala 1964b, p. 131 (Fig. 16)

- ↑ Sanchi Archaeological Museum website notice Archived 19 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Agrawala 1964b, p. 130 (Fig. 14)

Cited works

- Abdullaev, Kazim (2014). "The Buddhist culture of ancient Termez in old and recent finds". Parthica: Incontri di Culture Nel Mondo Antico. Pisa and Roma: Fabrizio Serra Editore. 15: 157–187.

- Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharan (1964a). The Heritage of Indian Art. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting.

- Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharan (1964b). Wheel Flag of India Chakra-dhvaja: being a history and exposition of the meaning of the Dharma-chakra and the Sarnath Lion Capital. Varanasi: Prithivi Prakashan. OCLC 1129478258.

- Allchin, F. R. (1995). "Mauryan architecture and art". The archaeology of early historic South Asia: the emergence of cities and states. With contributions by George Erdosy, R. A. E. Coningham, D. K. Chakrabarti and Bridget Allchin. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 222–273. ISBN 0521375479.

- Asher, Frederick M. (2020). Sarnath: A critical history of the place where Buddhism began. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute. pp. 2–3, 432–433. ISBN 9781606066164. LCCN 2019019885.

- Asher, Frederick (2011). "On Maurya Art". In Brown, Rebecca M.; Hutton, Deborah S. (eds.). A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture. Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Art History. Southern Gate, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 421–444. ISBN 9781444396355.

- Asher, Frederick M. (2006). "Early Indian Art Reconsidered". In Olivelle, Patrick (ed.). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 51–66. ISBN 9780195305326.

- Asif, Manan Ahmed (2020). The Loss of Hindustan: The Invention of India. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674249868.

- Boardman, John (1998). "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 13–22. JSTOR 24049089.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2021) [2017]. "Achaemenids and Mauryans: Emergence of Coins and Plastic Arts in India". In Patel, Alka; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). India and Iran during the Long Durée. Ancient Iran Series. Boston and Leiden: BRILL, originally, Irvine: UCI, Jordan Center for Persian Studies. ISBN 9789004460638.

- Coningham, Robin; Young, Ruth (2015). Archaeology of South Asia: From Indus to Asoka, c. 6500 BCE–200 CE. Cambridge World Archaeology Series. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-521-84697-4.

- Dolan, Marion (2021). "Art, Architecture, and Astronomy of Buddhism". Decoding Astronomy in Art and Architecture. Springer Nature Switzerland and Springer Praxis Books. pp. 107–128. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-76511-8. ISBN 978-3-030-76510-1. S2CID 240504248.

- Eaton, R. M. (2000). "Temple Desecration and Indo-Muslim States". Journal of Islamic Studies. Oxford University Press. 11 (3): 283–319. doi:10.1093/jis/11.3.283. JSTOR 26198197.

- Falk, Harry (2006). "Tidal waves of Indian history, new interpretations and beyond.". In Olivelle, Patrick (ed.). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oup USA. ISBN 9780195305326.

- Fogelin, Lars (2015). An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1999-4821-5.

- Guha, Sudeshna (2021) [2012]. "Material Truths and Religious Identities: The Archaeological and Photographic Making of Banaras". In Dodson, Michael S. (ed.). Banaras: Urban Forms and Cultural Histories. Routledge. pp. 42–74. ISBN 9781003157793.

- Guha, Sudeshna (2010). "Introduction: Archaeology, Photography, Histories". In Guha, Sudeshna (ed.). The Marshall Albums: Photography and Archaeology. Preface by B. D. Chattopadhyaya; Contributors: Sudeshna Guha, Michael S. Dodson, Tapati Guha-Thakurta, Christopher Pinney, Robert Harding. The Alkazi Collection of Photography in association with Mapin Publishing, and support of Archaeological Survey of India. p. 39. ISBN 978-81-89995-32-4.

- Harle, J. C. (1994) [1986]. The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (2nd ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06217-6.

- Huntington, John (1990). "Understanding the 5th century Buddhas of Sarnath" (PDF). Orientations. 40: 90, Fig.8.

- Irwin, John (1973). "'Aśokan' Pillars: A Reassessment of the Evidence". The Burlington Magazine. 115 (848): 706–720. JSTOR 877526.

- Irwin, John (1974). "'Aśokan' Pillars: A Reassessment of the Evidence-II: Structure". The Burlington Magazine. 116 (861): 712–727. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 877843.

- Irwin, John (1975). "'Aśokan' Pillars: A Re-Assessment of the Evidence - III: Capitals". The Burlington Magazine. 117 (871): 631–643. JSTOR 878154.

- Irwin, John (1990). "Origins of form and structure in monumental art". In Werner, Karel (ed.). Symbols in art and religion: the Indian and the comparative perspectives. London: Curzon Press. pp. 46–67. ISBN 9781136101144.

- Jansari, Sushma (2021). "South Asia". In Mairs, Rachel (ed.). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek worlds. The Routledge World Series. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 38–55. ISBN 978-1-138-09069-9. LCCN 2020022295.

- Maxwell, Gail (2004). "India, Buddhist Art". In Buswell, Robert E. Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. New York: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 360–366. ISBN 0-02-865718-7. LCCN 2003009965.

- Mitter, Partha (2001). Indian Art. Oxford History of Art Series. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284221-8.

- Oertel, F. O. (1908). "Excavations at Sarnath". Archaeological Survey of India: Annual Report 1904–1905. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India. pp. 59–104.

- Pabón-Charneco, Arleen (2021). Architecture History, Theory and Preservation: Prehistory to the Middle Ages. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-32676-7.

- Pal, Pratapaditya (2016). "Introduction: Piety, Puja, and Visual Images". In Pal, Pratapaditya (ed.). Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent. Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and University of California Press. pp. 19–54. ISBN 978-0-520-28847-8.

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2014). The Return of the Buddha: Ancient Symbols for a New Nation. Routledge. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-415-71115-9.

- Sahni, Daya Ram (1914). Catalogue of the Museum of Archaeology at Sarnath. With an introduction by J. Ph. Vogel. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India. pp. 28–31.

- Shelby, Karen (2021). "Identities Lost and Found in the Commemorative Landscapes of the Great War". Journal of Belgian History. LI (1–2): 100–118.

- Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97527-9. LCCN 2017008399.

- Sohoni, Pushkar (2017). "Old fights, new meanings: Lions and elephants in combat". Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics. Chicago and Cambridge MA: University of Chicago Press, published in association with the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. 67–68: 225–234. doi:10.1086/691602. S2CID 165605193.

- Stoneman, Richard (2019). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15403-9. LCCN 2018958249.

- Tadgell, Christopher (2008). The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven. Architecture in Context series II. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415407526.

- Tömory, Edith (1982). History Of Fine Arts In India And The West. Hyderabad: Orient Longmans. ISBN 0-86131-321-6.

- Vajpeyi, Ananya (2012). Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India. Cambridge MA and London: Harvard University Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-674-04895-9.

- Wriggins, Sally Hovey (2021) [1996]. Xuanzang: A Buddhist Pilgrim on the Silk Road. with a foreword by Frederick W. Motes. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-3672-1386-2.

Further reading

- Allen, Charles, Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor, 2012, Hachette UK, ISBN 1408703882, 9781408703885, google books

- Huntington, John (2009), Understanding The 5th century Buddhas of Sarnath: A newly identified Mudra and a new comprehension of the Dharmachakramudra (PDF), Orientations (journal), 40, p. 90, Fig.8 see Asher, p.139, note 34

- Mani, B. R. (2012), Sarnath : Archaeology, Art and Architecture, Archaeological Survey of India, p. 58

External links

- Blog with excellent photos

- For Pictures of the famous original "Lion Capital of Ashoka" preserved at the Sarnath Museum which has been adopted as the "National Emblem of India" and the Ashoka Chakra (Wheel) from which has been placed in the center of the "National Flag of India" - See "lioncapital" from Columbia University Website, New York, USA

- National symbols of India

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)