| Soukous | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Late 1960s in DRC and Republic of the Congo, 1980s in France |

| Derivative forms | Muziki wa dansi |

| Regional scenes | |

| Congolese sound (Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania), fast-paced soukous (Paris) | |

| Other topics | |

| Soukous musicians | |

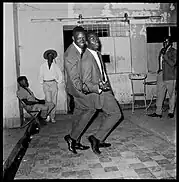

Soukous (from French secousse, "shock, jolt, jerk") is a genre of dance music originating from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) and the Republic of the Congo (formerly French Congo).[1] It derived from Congolese rumba in the 1960s, with faster dance rhythms and bright, intricate guitar improvisation,[2] and gained popularity in the 1980s in France.[3] Although often used by journalists as a synonym for Congolese rumba, both the music and dance associated with soukous differ from more traditional rumba, especially in its higher tempo, song structures and longer dance sequences.[3]

Soukous fuses traditional Congolese rhythms with contemporary instruments. It customarily incorporates electric guitars, double bass, congas, clips, a third guitar (misolo), and brass/woodwinds.[4][5] Soukous lyrics often explore themes of love, social commentary, amorous narratives, philosophical musings, and ordinary struggles and successes.[2] Singers occasionally sing and croon in Lingala, Kikongo, French and Swahili and bands often consist of a primary vocalist accompanied by several backing singers.[6][7]

History

Origins

The genre's origins can be traced back to the early 20th century when urban residents of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo embraced the fusion of intertribal Congolese maringa dance music near Pool Malebo, infused with guitar techniques from Liberia.[8] The outflow of Kru merchants and sailors from Liberia to Brazzaville during the mid-19th century introduced distinctive guitar-playing techniques that ultimately influenced the use of the accordion to emulate local "likembe" (thumb piano, best known worldwide as a mbira) rhythms.[8][9] As early as 1902, the accordion's melodies resonated through the streets near Pool Malebo's factories.[8]

The outbreak of World War I introduced a new wave of music and dance across the Lower Congo (present-day Kongo Central) and the Pool Malebo region.[8] Emerging from labor camp and conceivably associated with the return of Matadi–Kinshasa Railway construction workers, local dances such as agbaya and maringa gained prominence.[8] The circular agbaya dance was soon replaced by partnered maringa dance music, becoming increasingly ubiquitous in Matadi, Boma, Brazzaville, and Kinshasa.[8] Initially, maringa bands featured the likembe for melody, a metal rod-struck bottle for rhythm, and a small skin-covered frame drum called patenge for counter-rhythms.[8] However, by the 1920s, accordions and acoustic guitars progressively supplanted the likembe as the quintessential melody instruments. The distinctive hip movements of maringa dancers, shifting their body weight between legs.[8] By 1935, partnered dancing's popularity dispersed expeditiously across the Congo basin, reaching even remote villages. Dance halls emerged in towns and rural areas, while conventional dancing persisted in palm branch huts.[8] In the early 1940s, Pool Malebo transformed from a barrier into a communication channel linking Brazzaville and Kinshasa.[8] The Cuban son groups like Sexteto Habanero, Trio Matamoros, and Los Guaracheros de Oriente were broadcast on Radio Congo Belge, gaining popularity in the country.[8][10][11] The maringa dance music—although unrelated to Cuban rumba—bore cultural homogeneity to Afro-Cubans, and was swiftly adopted throughout the Congo basin region with Cuban son influence.[8][12]

By the mid-1940s, the culturally homogenous maringa dance music became known as "rumba Congolaise" as the imported records of Sexteto Habanero and Trio Matamoros were often mislabelled as "rumba".[13] Ethnomusicology Professor Kazadi wa Mukuna of Kent State University explicates that the term "rumba" persisted in the Congos due to recording industry interests. Recording studio proprietors reinterpreted the term rumba by attributing it new maringa rhythm while retaining the name.[13] Consequently, their music became recognized as "Congolese rumba" or "African rumba". Antoine Wendo Kolosoy became the first star of Congolese rumba touring Europe and North America with his band Victoria Bakolo Miziki. His 1948 hit "Marie-Louise," co-written with guitarist Henri Bowane, gained popularity across West Africa.[14][15] Bowane guitar solos invoked the sound of traditional likembe and stringed instruments played in the region. In Kinshasa's bars, Bowane reportedly extended these solos into an extended dancing section, which later became known locally as seben(e) in the 1970s. The "sebene", alongside the Congolese rumba, gained prominence in Congolese music as early pioneers revolutionized their relationship with the instruments they held.[16][17]

Formation

In the 1960s, a new wave of youth bands, often referred to as yéyé, garnered attention, overshadowing established figures like Franco Luambo and Tabu Ley Rochereau with their rhythms and dances. They elevated the rumba's tempo, elongated the seben, and coined a new name: secousse, from the French secouer, meaning "to shake."[16] Artists began incorporating faster rhythms, prominent guitar improvisation, and more distinct African elements. The drummer shifts to the high-energy beat, where the clave rhythm shifts to the snare drum, singers engage in rhythmic chanting (animation), and lead guitars take center stage. Franco Luambo, along with his band TPOK Jazz, is credited with pioneering the genre. He is also conceded for revolutionizing the genre's themes by infusing momentous social and political issues into the lyrics, transforming the music into a platform for social consciousness.[18][2][19][20] Tabu Ley Rochereau and Dr. Nico Kasanda formed African Fiesta and transformed their music further by fusing Congolese folk music with soul music, as well as Caribbean and Latin beats and instrumentation. They were joined by Papa Wemba and Sam Mangwana, and classics like "Afrika Mokili Mobimba" propelled them as one of Africa's most prominent bands.[21][22][23][24] The soukous scene blossomed due to limited employment prospects for youths in Zaire, with pursuing a career as a musician in Kinshasa's burgeoning soukous scene becoming one of the few available paths.[13]

1970s

At its peak in the 1970s, soukous dominated East African nightclubs' dance floors and played a pivotal role in shaping virtually all the styles of contemporary African popular music, including benga music, muziki wa dansi, highlife, palm-wine music, taarab, and inspiring the establishment of approximately 350 youth orchestras in Kinshasa, paving the way for new traditional dances, rhythmic patterns, and bands.[25][26][27][28]

As sociopolitical turmoil in Zaire deteriorated in the 1970s, a great number of musicians ventured to Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Colombia, and many migrated en masse to Paris and Brussels. By the mid-1970s, several Congolese bands had taken up the Soukous beat in Kenyan nightclubs.[29][30][31][32][33] The vivacious cavacha dance craze, propagated by bands like Zaiko Langa Langa and Orchestra Shama Shama, swept East and Central Africa, exert influence on Kenyan musicians.[34] Played on the snare drum or hi-hat, expeditiously became a trademark of the Zairean sound in Nairobi and was habitually used by regional bands. Prominent Congolese rumba Swahili bands in Nairobi formed around Tanzanian groups like Simba Wanyika, giving rise to offshoots like Les Wanyika and Super Wanyika Stars.[35][36][37] Maroon Commandos, a Nairobi-based group, emulated the soukous style while infusing their unique flair. Japanese students in Kenya, including Rio Nakagawa, became enamored with Congolese music. Rio embraced Lingala and eventually led Yoka Choc Nippon, a Japanese-made Congolese rumba group.[38]

Virgin Records produced LPs by the Tanzanian-Zairean Orchestra Makassy and the Kenya-based Orchestra Super Mazembe. The Swahili track Shauri Yako ("It's your problem") became a magnum opus in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. Another prestigious influential Zairean group, Les Mangelepa, moved to Kenya and gained immense popularity across East Africa. Congolese vocalist Samba Mapangala and his band Orchestra Virunga, based in Nairobi, released the LP "Malako," which became a pioneering release in Europe's emerging world music scene.[39][40][41]

During this epoch, African music began procuring popularity globally due to the world music movement. In Colombia, soukous gained traction, influencing local culture and playing a pivotal role in pioneering champeta.[42][43] Zairean sailors introduced their records to Colombia, including the plate-numbered 45 RPM "El Mambote" by Congo's l'Orchestre Veve, which gained popularity.[44] The locals began replicating musical arrangements by Congolese luminaries like Nicolas Kasanda wa Mikalay, Tabu Ley Rochereau, M'bilia Bel, Syran Mbenza, Lokassa Ya M'Bongo, Pépé Kallé, Rémy Sahlomon, and Kanda Bongo Man. Homegrown talents like Viviano Torres, Luis Towers, and Charles King added their original compositions to the mix, maintaining the core essence of Congolese soukous.[45][46][47]

1980s and the Paris scene

Soukous became popular in London and Paris in the 1980s and was the only sub-Saharan African genre universally embraced in France and Belgium. A few more musicians left Kinshasa to work around Central and East Africa before settling in either the UK or France.[29][48][2][49][50] By the mid-1980s, Parisian studios were used by many soukous artists, and the music became heavily reliant on synthesizers and other electronic instruments. Some artists continued to record for the Congolese market, but others abandoned the demands of the Kinshasa public and set out to pursue new audiences. Some, like Paris-based Papa Wemba maintained two bands, Viva La Musica for soukous, and a group including French session players for international pop.[51][52]

Kanda Bongo Man, another Paris-based artist, pioneered fast, short tracks suitable for play on dance floors everywhere and popularly known as kwassa kwassa after the dance moves popularized by his and other artists' music videos. This music appealed to Africans and to new audiences as well. Artists like Diblo Dibala, Aurlus Mabele, Tchicl Tchicaya, Jeannot Bel Musumbu, Mbilia Bel, Yondo Sister, Tinderwet, Loketo, Rigo Star, Madilu System, Soukous Stars and veterans like Pepe Kalle and Koffi Olomide followed suit. Soon Paris became home to talented studio musicians who recorded for the African and Caribbean markets and filled out bands for occasional tours.[29][54]

In the early 2000s, ndombolo, a genre named after a dance, gained widespread appeal, blending influences from soukous, kwassa kwassa, and Congolese rumba.[55]

Musical form

The basic line-up for a soukous band included three or four guitars, bass guitar, drums, brass, and vocals.[56] A soukous arrangement commences with a rumba section featuring intricate harmony. However, as the song progresses into the mid-tempo and final fast sections, harmony often simplifies to three chords.[57] In Matonge, the rhythmic guitar typically chaperones mid-tempo vocals, with bass and bass drums emphasizing strong beats while guitarists accentuate offbeats (one and two and three and four and).[57] During singing, the lead guitarist creates a groove to support harmonized call-and-response vocals.[57] Soukous lead guitarists are celebrated for their speed, precision, and nimble fingerwork, often high on the fretboard.[57]

Franco Luambo popularized placing the sebene at a song's end and using a thumb-and-forefinger picking technique for a sonic illusion of two guitar lines.[27] Sebene originates from "seven," referencing dominant 7th chords from English-speaking Ghanaian palm-wine players.[57] During a seben, the drummer signals changes, guiding guitarists to shift parts in sync with the lead player. The typical Congolese progression for sebens is I-IV-V-IV. Collaborating with other guitarists and a drummer enhances proficiency.[57]

Soukous bass parts, derived from hand-drum percussion, contribute strong rhythm and harmony. Emerging during Mobutu Sese Seko's regime in Zaire, soukous music's aggressive bass style imitated soldiers' movements, known as marche militaire. This bass style involves toggling between low and high lines, employing picking with p and i.[57]

Ndombolo

The hip-swinging dance of the fast paced soukous ndombolo has come under criticism on claims that it is obscene. There have been attempts to ban it in Mali, Cameroon and Kenya. After an attempt to ban it from state radio and television in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2000, it became even more popular. In February 2005, ndombolo music videos in the DR Congo were censored for indecency, and video clips by Koffi Olomide, JB M'Piana and Werrason were banned from the airwaves.[58][59][60]

See also

References

- ↑ Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 407–408. ISBN 9780195337709.

- 1 2 3 4 Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 407–408. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- 1 2 Peek, Philip M.; Yankah, Kwesi (2004). African Folklore: An Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 548. ISBN 9781135948733.

- ↑ Davies, Carole Boyce (July 29, 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture [3 volumes]. Santa Barbara, California: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- ↑ Domosh, Mona; Jordan-Bychkov, Terry G.; Neumann, Roderick P.; Price, Patricia L. (2012). The Human Mosaic. Macmillan. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-4292-7200-1.

- ↑ Olwig, Karen Fog; Sorensen, Ninna Nyberg (August 27, 2003). Work and Migration: Life and Livelihoods in a Globalizing World. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-134-50306-3.

- ↑ Russell, K.F. (1997). Rhythm Music Magazine: RMM. K.F. Russell. p. 45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Martin, Phyllis (August 8, 2002). Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–152. ISBN 978-0-521-52446-9.

- ↑ Kubik, Gerhard (October 30, 2010). Theory of African Music, Volume I. Chicago, Illinois, United States: University of Chicago Press. pp. 384–385. ISBN 978-0-226-45691-1.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Africa v. 1. 2010 p. 407.

- ↑ Storm Roberts, John (1999). The Latin Tinge: The Impact of Latin American Music on the United States (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-0-19-976148-7.

- ↑ Edward-Ekpu, Uwagbale (December 21, 2021). "Rumba's Congolese roots are finally being recognized by Unesco". Quartz. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Mukuna, Kazadi wa (December 7, 2014). "A brief history of popular music in DRC". Music In Africa. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ↑ "Les années 1970: L'âge d'or de la musique congolaise" [The 1970s: The Golden Age of Congolese Music]. Mbokamosika (in French). August 18, 2009. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ "'Father' of Congolese rumba dies". BBC. July 30, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- 1 2 Greenstreet, Morgan (December 7, 2018). "Seben Heaven: The Roots of Soukous". daily.redbullmusicacademy.com. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ Ossinonde, Clément (August 2, 2017). "Qui est à l'origine du "Sebene" dans la musique congolaise ? Sa notation musicale ?". Pagesafrik.com (in French). Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ AP (1989). "Franco, 51, Zairian Band Leader And Creator of the Soukous Style". The New York Times. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ Appiah, Anthony; Gates (Jr.), Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- ↑ African, New (August 15, 2018). "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African Magazine. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ Roberts, John Storm. Afro-Cuban Comes Home: The Birth and Growth of Congo Music. Original Music cassette tape (1986).

- ↑ Kisangani, Emizet Francois (November 18, 2016). Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 576. ISBN 978-1-4422-7316-0.

- ↑ Sfetcu, Nicolae (May 9, 2014). Dance Music. Nicolae Sfetcu. p. 50.

- ↑ Koskoff, Ellen (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Africa ; South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean ; The United States and Canada ; Europe ; Oceania. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-415-99403-3.

- ↑ Stone, Ruth M., ed. (April 2, 2010). The Garland Handbook of African Music. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781135900014.

- ↑ Messager (August 18, 2009). "Les années 1970: L'âge d'or de la musique congolaise". Mbokamosika (in French). Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- 1 2 African, New (August 15, 2018). "The mixed legacy of DRC musician Franco". New African Magazine. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ↑ Sturman, Janet (February 26, 2019). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Music and Culture. Thousand Oaks, California, United States: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-5063-5338-8.

- 1 2 3 Davies, Carole Boyce (July 29, 2008). Encyclopedia of the African Diaspora [3 volumes]: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. New York City, New York State, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 849. ISBN 978-1-85109-705-0.

- ↑ Trillo, Richard (2016). The Rough Guide to Kenya. London, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 598. ISBN 9781848369733.

- ↑ Stewart, Gary (May 5, 2020). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Brooklyn, New York City, New York State: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-78960-911-0.

- ↑ Valdés, Vanessa K., ed. (June 2012). Let Spirit Speak!: Cultural Journeys Through the African Diaspora. Albany, New York City, New York State: State University of New York Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781438442174.

- ↑ Hodgkinson, Will (July 8, 2010). "How African music made it big in Colombia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ↑ Adieu, Verckys (October 19, 2022). "congolese rumba". Cavacha Express! Classic congolese hits. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ Stone, Ruth M., ed. (April 2, 2010). The Garland Handbook of African Music. Thames, Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. pp. 132–133. ISBN 9781135900014.

- ↑ "congolese rumba". Cavacha Express! Classic congolese hits. October 19, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ Trillo, Richard (2016). The Rough Guide to Kenya. London, United Kingdom: Rough Guides. p. 598. ISBN 9781848369733.

- ↑ Mwamba, Bibi (February 7, 2022). "L'influence de la rumba congolaise sur la scène musicale mondiale". Music in Africa (in French). Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ↑ "Shauri Yako — Orchestra Super Mazembe". Last.fm. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ "congo in kenya". muzikifan.com. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ Nyanga, Caroline. "Stars who came for music and found eternal resting place". The Standard. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ Malandra, Ocean (December 2020). Moon Cartagena & Colombia's Caribbean Coast. New York City, New York State, United States: Avalon Publishing. ISBN 9781640499416.

- ↑ Koskoff, Ellen, ed. (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Africa; South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean; The United States and Canada; Europe; Oceania. Oxfordshire, England, United Kingdom: Routledge. p. 185.

- ↑ Hodgkinson, Will (July 8, 2010). "How African music made it big in Colombia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ↑ Valdés, Vanessa K., ed. (June 2012). Let Spirit Speak!: Cultural Journeys Through the African Diaspora. Albany, New York City, New York State: State University of New York Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781438442174.

- ↑ Slater, Russ (January 17, 2020). "Colombia's African Soul". Long Live Vinyl. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ↑ Hodgkinson, Will (July 8, 2010). "How African music made it big in Colombia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin; Jean-Jacques, Daniel (December 14, 2015). Africa [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. New York City, New York State, United States: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 979-8-216-04273-0.

- ↑ Orlean, Susan (October 6, 2002). "The Congo Sound". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ Daoudi, Bouziane (August 29, 1998). "World. Le chanteur ex-zaïrois en concert à l'Olympia. Koffi Olomidé, Rambo de la rumba. Koffi Olomidé. Samedi à 23 heures à l'Olympia, 28, bd des Capucines, Paris IXe. Tél.: 01 47 42 25 49. Album: «Loi», Sonodisc" [World. The ex-Zairian singer in concert at the Olympia. Koffi Olomidé, Rambo of rumba. Koffi Olomide. Saturday at 11 p.m. at the Olympia, 28, bd des Capucines, Paris 9th. Tel.: 01 47 42 25 49. Album: “Law”, Sonodisc.]. Libération (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ↑ Stewart, Gary (May 5, 2020). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Brooklyn, New York City: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-78960-911-0.

- ↑ Vogel, Christoph; Network, part of the Guardian Africa (August 23, 2013). "Say my name: How 'shout-outs' keep Congolese musicians in the money". the Guardian. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Kanda Bongo Man dances a new dance". BBC News. September 29, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Kanda Bongo Man dances a new dance". BBC News. September 29, 2014. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ Powell, Azizi (May 27, 2014). "pancocojams: Nyboma & Pepe Kalle with Dally Kimoko - "Nina" (Congolese Soukous Music)". pancocojams. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ Boomer, Tim; Berry, Mick; Bufe, Chaz (January 1, 2014). Bassist's Bible: How to Play Every Bass Style from Afro-Cuban to Zydeco. See Sharp Press. ISBN 978-1-937276-25-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eyre, Banning (2002). Africa: Your Passport to a New World of Music. Los Angeles, California, United States: Alfred Music Publishing. pp. 12–17. ISBN 978-0-7390-2474-4.

- ↑ "Anger at Cameroon dance ban; BBC News", BBC News, July 25, 2000

- ↑ "Ndombolo music videos in DR Congo censored for indecency, Lifestyle News, February 11, 2005"

- ↑ "Why is this 'Ndombolo' generating so much heat?", Daily Nation (Kenya) October 11, 1998

Bibliography

- Gary Stewart (2000). Rumba on the River: A History of the Popular Music of the Two Congos. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-368-9.

- Wheeler, Jesse Samba (March 2005). "Rumba Lingala as Colonial Resistance". Image & Narrative (10). Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved July 14, 2014.