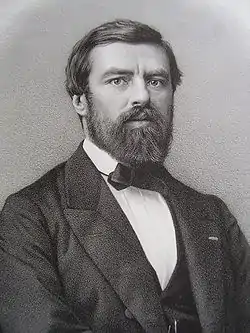

Léopold Victor Delisle (24 October 1826, Valognes (Manche) – 21 July 1910, Chantilly, Oise) was a French bibliophile and historian.

Biography

Early life

He was taken on as a young man by the antiquarian and historian of architecture, Charles-Alexis-Adrien Duhérissier de Gerville, who engaged him to copy manuscripts in his collection, and taught him enough of the basics of paleography that he was able to gain entrance to the École des Chartes in 1846. Here, Delisle's career was remarkably brilliant and he published his first article on mortuary rolls in 1847.[1] His valedictory thesis was an Essai sur les revenus publics en Normandie au XIIe siècle (1849), drawn in part from manuscripts of Duhérissier de Gerville, who was Delisle's mentor, and it was to the history of his native Normandy that he devoted his early works. Of these the Études sur la condition de la classe agricole et l'état de l'agriculture en Normandie au Moyen Âge (1851), condensing an enormous mass of facts drawn from the local archives, was reprinted in 1905 without change, and remains authoritative.

Bibliothèque nationale

In November 1852 he entered the manuscript department of the Bibliothèque imperiale (nationale), of which in 1874 he became the official head in succession to Jules Taschereau. He was already known as the compiler of several invaluable inventories of its manuscripts. When the French government decided on printing a general catalogue of the printed books in the Bibliothèque, Delisle became responsible for this undertaking and took an active part in the work; in the preface to the first volume (1897) he gave a detailed history of the library and its management.

Under his administration the library was enriched with numerous gifts, legacies and acquisitions, notably by the purchase of a part of the Ashburnham manuscripts. Delisle proved that the bulk of the manuscripts of French origin which the Earl of Ashburnham had bought in France, particularly those bought from the book-seller Jean-Baptiste Barrois, had been purloined by Count Libri, inspector-general of libraries under King Louis-Philippe, and he procured the repurchase of the manuscripts for the library, afterwards preparing a catalogue of them entitled Catalogue des manuscrits des fonds Libri et Barrois (1888), the preface of which gives the history of the whole transaction. He was elected member of the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres in 1859, and became a member of the staff of the Recueil des historiens de la France, collaborating in vols xxii. (1865) and xxiii. (1876) and editing vol. xxiv. (1904), which is valuable for the social history of France in the 13th century.

When the Paris Commune sought to replace him with an unqualified appointee during the siege of Paris in 1870, Delisle courageously refused to leave his post.[2] The jubilee of his fifty years' association with the Bibliothèque nationale was celebrated on 8 March 1903.

Retirement

After his retirement (21 February 1905) he brought out in two volumes a catalogue and description of the printed books and manuscripts in the Musée Condé at Chantilly, left by the duc d'Aumale to the French Institute. He produced many valuable official reports and catalogues and a great number of memoirs and monographs on points connected with palaeography and the study of history and archaeology (see his Mélanges de paleographie et de bibliographie (1880) with atlas; and his articles in the Album paléographique (1887).

Scholarly work

Of his purely historical works special mention must be made of his Mémoire sur les actes d'Innocent III (1857), and his Mémoire sur les operations financières des Templiers (1889), a collection of documents of the highest value for economic history. The thirty-second volume of the Histoire littéraire de la France, which was partly his work, is of great importance for the study of 13th and 14th century Latin chronicles.

Delisle was undoubtedly the most learned man in Europe with regard to the Middle Ages; and his knowledge of diplomatics, palaeography and printing was profound. His output of work, in catalogues, etc., was enormous, and his services to the Bibliothèque nationale in this respect cannot be overestimated. The Bibliographie des travaux de L. Delisle (1902), by Paul Lacombe, may be consulted for a full list of his numerous works.

Private life

Delisle was a patriot (both French and Norman) and a Christian. He was motivated to a great extend by the destruction the French Revolution had brought upon medieval manuscripts and buildings; for Delisle, the publication of texts was necessary not only for the preservation of the past but also of civilisation.[2] He married on 10 June 1857 Louise-Laure Burnof, daughter of Eugène Burnouf, who was for many years his collaborator. She acquired skill as a Latin palaeographer and contributed to her husband's work through her knowledge of several languages, a weak point of Delisle. Their marriage, though affectionate, was childless which both regretted. Loise-Laure Burnof died on 11 March 1905, a few days after the couple had learned of his retirement in the Journal officiel.[2]

References

- ↑ Bates 2014, p. 104.

- 1 2 3 Bates 2014, p. 103.

Sources

- Dictionary of Art Historians: "Léopold Victor Delisle"

- Conference on Léopold Delisle, 2004

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Delisle, Leopold Victor". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 964.

- Bates, David (June 2014). Damico, Helen; Zavadil, Joseph (eds.). Medieval Scholarship Biographical Studies on the Formation of a Discipline: History · Volume 1. Taylor & Francis. pp. 101–114. ISBN 9781317943341. Retrieved 19 April 2023.