Lebanese Republic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polity type | Unitary Parliamentary republic democratic republic |

| Constitution | Constitution of Lebanon |

| Legislative branch | |

| Name | Parliament of Lebanon |

| Type | Unicameral |

| Meeting place | Parliament Building in Beirut |

| Presiding officer | Nabih Berri, Speaker |

| Executive branch | |

| Head of State | |

| Title | President |

| Currently | Vacant |

| Appointer | Elected by Parliament |

| Head of Government | |

| Title | Prime Minister |

| Currently | Najib Mikati |

| Appointer | President, on parliament’s advice |

| Cabinet | |

| Name | Council of Ministers |

| Leader | Prime Minister |

| Appointer | The Prime Minister with the President |

| Judicial branch | |

| Name | Judicial branch |

|

|---|

|

|

Lebanon is a parliamentary democratic republic within the overall framework of confessionalism, a form of consociationalism in which the highest offices are proportionately reserved for representatives from certain religious communities. The constitution of Lebanon grants the people the right to change their government. However, from the mid-1970s until the parliamentary elections in 1992, the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) precluded the exercise of political rights.

According to the constitution, direct elections must be held for the parliament every four years, however after the parliamentary election in 2009[1] another election was not held until 2018. The Parliament, in turn, elects a president every six years to a single term. The president is not eligible for re-election. The last presidential election was in 2016. The president and parliament choose the prime minister. Political parties may be formed; most are based on sectarian interests. 2008 saw a new twist to Lebanese politics when the Doha Agreement set a new trend where the opposition is allowed a veto power in the Council of Ministers and confirmed religious confessionalism in the distribution of political power. The Economist Intelligence Unit classified Lebanon as a "hybrid regime" in 2016.[2]

Overview

The Maronite Catholics and the Druze founded modern Lebanon in the early eighteenth century, through the ruling and social system known as the "Maronite-Druze dualism" in Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate.[3] Since the emergence of the post-1943 state and after the destruction of the Ottoman Caliphate, national policy has been determined largely by a relatively restricted group of traditional regional and sectarian leaders. The 1943 National Pact, an unwritten agreement that established the political foundations of modern Lebanon, allocated political power on an essentially confessional system based on the 1932 census. Seats in parliament were divided on a 6-to-5 ratio of Christians to Muslims, until 1990 when the ratio changed to half and half. Positions in the government bureaucracy are allocated on a similar basis. The pact also by custom allocated public offices along religious lines, with the top three positions in the ruling "troika" distributed as follows: the president, a Maronite Christian; the speaker of the Parliament, a Shi'a Muslim; and the prime minister, a Sunni Muslim.

Efforts to alter or abolish the confessional system of allocating power have been at the centre of Lebanese politics for decades. Those religious groups most favoured by the 1943 formula sought to preserve it, while those who saw themselves at a disadvantage sought either to revise it after updating key demographic data or to abolish it entirely. Nonetheless, many of the provisions of the national pact were codified in the 1989 Taif Agreement, perpetuating sectarianism as a key element of Lebanese political life.

Although moderated somewhat under Ta'if, the Constitution gives the president a strong and influential position. The president has the authority to promulgate laws passed by the Parliament, form the government to issue supplementary regulations to ensure the execution of laws, and to negotiate and ratify treaties.

The Parliament is elected by adult suffrage (majority age for election is 21)[4] based on a system of majority or "winner-take-all" for the various confessional groups. There has been a recent effort to switch to proportional representation which many argue will provide a more accurate assessment of the size of political groups and allow minorities to be heard. Most deputies do not represent political parties as they are known in the West, and rarely form Western-style groups in the assembly. Political blocs are usually based on confessional and local interests or on personal/family allegiance rather than on political affinities.

The parliament traditionally has played a significant role in financial affairs, since it has the responsibility for levying taxes and passing the budget. It also exercises political control over the cabinet through formal questioning of ministers on policy issues and by requesting a confidence debate.

Lebanon's judicial system is based on the Napoleonic Code. Juries are not used in trials. The Lebanese court system has three levels—courts of first instance, courts of appeal, and the court of cassation. There also is a system of religious courts having jurisdiction over personal status matters within their own communities, e.g., rules on such matters as marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Lebanese political institutions often play a secondary role to highly confessionalized personality-based politics. Powerful families also still play an independent role in mobilizing votes for both local and parliamentary elections. Nonetheless, a lively panoply of domestic political parties, some even predating independence, exists. The largest are all confessional based. The Free Patriotic Movement, The Kataeb Party, also known as the Phalange Party, the National Bloc, National Liberal Party, Lebanese Forces and the Guardians of the Cedars (now outlawed) each have their own base among Christians. Amal and Hezbollah are the main rivals for the organized Shi'a vote, and the PSP (Progressive Socialist Party) is the leading Druze party. While Shi'a and Druze parties command fierce loyalty to their leaderships, there is more factional infighting among many of the Christian parties. Sunni parties have not been the standard vehicle for launching political candidates, and tend to focus across Lebanon's borders on issues that are important to the community at large. Lebanon's Sunni parties include Hizb ut-Tahrir, Future Movement, Independent Nasserist Organization (INO), the Al-Tawhid, and Ahbash. Besides the traditional confessional parties above, new secular parties have emerged amongst which Sabaa and the Party of Lebanon[5] representing a new trend in Lebanese politics towards secularism and a truly democratic society. In addition to domestic parties, there are branches of pan-Arab secular parties (Ba'ath parties, socialist and communist parties) that were active in the 1960s and throughout the period of civil war.

There are differences both between and among Muslim and Christian parties regarding the role of religion in state affairs. There is a very high degree of political activism among religious leaders across the sectarian spectrum. The interplay for position and power among the religious, political, and party leaders and groups produces a political tapestry of extraordinary complexity.

In the past, the system worked to produce a viable democracy. Events over the last decade and long-term demographic trends, however, have upset the delicate Muslim–Christian–Druze balance and resulted in greater segregation across the social spectrum. Whether in political parties, places of residence, schools, media outlets, even workplaces, there is a lack of regular interaction across sectarian lines to facilitate the exchange of views and promote understanding. All factions have called for a reform of the political system.

Some Christians favor political and administrative decentralization of the government, with separate Muslim and Christian sectors operating within the framework of a confederation. Muslims, for the most part, prefer a unified, central government with an enhanced share of power commensurate with their larger share of the population. The reforms of the Ta'if agreement moved in this direction but have not been fully realized.

Palestinian refugees, predominantly Sunni Muslims, whose numbers are estimated at between 160,000 and 225,000, are not active on the domestic political scene.

On 3 September 2004, the Lebanese Parliament voted 96–29 to amend the constitution to extend President Émile Lahoud's six-year term (which was about to expire) by another three years. The move was supported by Syria, which maintained a large military presence in Lebanon.

Former prime minister Rafic Hariri was assassinated in February 2005.[6] Following the withdrawal of Syrian troops in April 2005, Lebanon held parliamentary elections in four rounds, from 29 May to 19 June. The elections, the first for 33 years without the presence of Syrian military forces, were won by the Quadripartite alliance, which was part the Rafik Hariri Martyr List, a coalition of several parties and organizations newly opposed to Syrian domination of Lebanese politics.

In January 2015, the Economist Intelligence Unit released a report stating that Lebanon ranked the second in Middle East and 98th out of 167 countries worldwide for Democracy Index 2014. The index ranks countries according to election processes, pluralism, government functions, political participation, political cultures and fundamental freedoms.

From October 2019, there have been mass protests against the government. In August 2020, a large explosion in Beirut killed at least 204 people and caused at least US$3 billion in property damage. Following the explosion and protests against the government, the prime minister and his cabinet resigned.[7]

In May 2022, Lebanon held its first election since a painful economic crisis dragged it to the brink of becoming a failed state. Lebanon's crisis has been so severe that more than 80 percent of the population is now considered poor by the United Nations. In the election Iran-backed Shia Muslim Hezbollah movement and its allies lost their parliamentary majority. Hezbollah did not lose any of its seats, but its allies lost seats. Hezbollah’s ally, President Michel Aoun's Free Patriotic Movement, was no longer the biggest Christian party after the election. A rival Christian party, led by Samir Geagea, with close ties to Saudi Arabia, the Lebanese Forces (LF), made gains. Sunni Future Movement, led by former prime minister Saad Hariri, did not participate the election, leaving a political vacuum to other Sunni politicians to fill.[8] [9] [10]

Executive branch

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | vacant | N/A | 31 October 2022 |

| Prime Minister | vacant (Najib Mikati caretaker) | Azm Movement | 14 May 2022 |

| Speaker of the Parliament | Nabih Berri | Amal Movement | 20 October 1992 |

The president is elected by the Parliament for a six-year term and cannot be reelected again until six years have passed from the end of the first term.[11] The prime minister and deputy prime minister are appointed by the president in consultation with the Parliament; the president is required to be a Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni, and the speaker of the Parliament a Shi'a. (See list of the ministers and their political affiliation for a list of ministers.)

This confessional system is based on 1932 census data which showed the Maronite Christians as having a substantial majority of the population. The Government of Lebanon continues to refuse to undertake a new census.

The president

Lebanon operates under a strong semi-presidential system. This system is unique in that it grants the president wide unilateral discretion, does not make him accountable to Parliament (unless for treason), yet is elected by the Parliament. The president has the sole power to appoint the prime minister, and may dismiss them at any point (without input from the Chamber of Deputies, which can also force the president to resign). In addition, the president has the sole authority to form a government (which must then receive a vote-of-confidence from Parliament) and dismiss it when they wish. This thus makes Lebanon a president-parliamentary system rather than a premier-presidential system (such as France), as the president does not have to cohabitate with a prime minister he dislikes. The historical reason for the broad powers of the president are that their powers were merged with those of the French high commissioner of Greater Lebanon, thus creating an exceptionally powerful presidency for semi-presidential systems.[12]

Following the end of the Lebanese Civil War, the president lost some powers to the Council of Ministers through the Taif Agreement; being the sole person who appoints it, however, they de facto still retain all (or most) of their pre-Taif powers.

Legislative branch

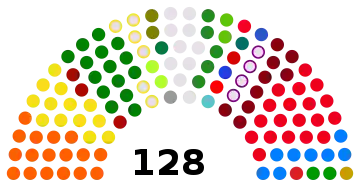

Lebanon's national legislature is called the Assembly of Representatives (Majlis al-Nuwab in Arabic). Since the elections of 1992 (the first since the reforms of the Taif Agreement of 1989 removed the built-in majority previously enjoyed by Christians and distributed the seats equally between Christians and Muslims), the Parliament has had 128 seats. The term was four years, but has recently been extended to five.

Seats in the Parliament are confessionally distributed but elected by universal suffrage. Each religious community has an allotted number of seats in the Parliament. They do not represent only their co-religionists, however; all candidates in a particular constituency, regardless of religious affiliation, must receive a plurality of the total vote, which includes followers of all confessions. The system was designed to minimize inter-sectarian competition and maximize cross-confessional cooperation: candidates are opposed only by co-religionists, but must seek support from outside of their own faith in order to be elected.

The opposition Qornet Shehwan Gathering, a group opposed to the former pro-Syrian government, has claimed that constituency boundaries have been drawn so as to allow many Shi'a Muslims to be elected from Shi'a-majority constituencies (where the Hezbollah Party is strong), while allocating many Christian members to Muslim-majority constituencies, forcing Christian politicians to represent Muslim interests. (Similar charges, but in reverse, were made against the Chamoun administration in the 1950s).

The following table sets out the confessional allocation of seats in the Parliament before and after the Taif Agreement.

| Confession | Before Taif | After Taif |

|---|---|---|

| Maronite Catholic | 30 | 34 |

| Eastern Orthodox | 11 | 14 |

| Melkite Catholic | 6 | 8 |

| Armenian Orthodox | 4 | 5 |

| Armenian Catholic | 1 | 1 |

| Protestant | 1 | 1 |

| Other Christian Minorities | 1 | 1 |

| Total Christians | 54 | 64 |

| Sunni | 20 | 27 |

| Shi'ite | 19 | 27 |

| Alawite | 0 | 2 |

| Druze | 6 | 8 |

| Total Muslims + Druze | 45 | 64 |

| Total | 99 | 128 |

Current parliament

March 8 Alliance (caretaker government) (60)

- Strong Lebanon Bloc (20)

- Development and Liberation Bloc (15)

- Amal Movement (14)

- Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party (1)

- Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc (15)

- Hezbollah (13)

- Independents (2)

- March 8 Affiliates (10)

- Independents (4)

- Marada Movement (2)

- Al-Ahbash (2)

- PNO (1)

- Union Party (1)

March 14 Alliance (38)

- Strong Republic Bloc (22)

- Ex-Future Movement (8)

- Kataeb Party (5)

- Independence Movement (2)

- Islamic Group (1)

Other Opposition (30)

- Civil Society (13)

- Independent (4)

- Taqaddum (2)

- Tahalof Watani (1)

- LCP (1)

- ReLebanon (1)

- Beirut Tuqawem (1)

- Khatt Ahmar (1)

- Lana (1)

- Osos Lebanon (1)

- Democratic Gathering Bloc (9)

- PSP (8)

- Independents (1)

- Independents (8)

Judicial branch

Lebanon is a civil law country. Its judicial branch is composed of:

- Ordinary Courts:

- One Court of Cassation composed of nine chambers [13]

- Courts of Appeal (in the centre of every governorate) [13]

- Courts of First Instance [13]

- Special Courts:

- The Constitutional Council (called for in the Taif Agreement) rules on constitutionality of laws

- The Supreme Council hears charges against the president and prime minister as needed.

- A system of military courts that also has jurisdiction over civilians for the crimes of espionage, treason, and other crimes that are considered to be security-related.[14]

Political parties and elections

Lebanon has numerous political parties, but they play a much less significant role in Lebanese politics than they do in most parliamentary democracies. Many of the "parties" are simply lists of candidates endorsed by a prominent national or local figure. Loose coalitions, usually organized locally, are formed for electoral purposes by negotiation among clan leaders and candidates representing various religious communities; such coalitions usually exist only for the election, and rarely form a cohesive block in the Parliament after the election. No single party has ever won more than 12.5 percent of the seats in the Parliament, and no coalition of parties has won more than 35 percent.

Especially outside of the major cities, elections tend to focus more on local than national issues, and it is not unusual for a party to join an electoral ticket in one constituency while aligned with a rival party – even an ideologically opposite party – in another constituency.

It is not uncommon for election times to be accompanied by outbreaks of violence, especially in polling areas where there are people of conflicting political and religious backgrounds. Sectarianism is so ingrained into Lebanese politics and society that citizens supporting their political parties will kill or be killed defending them.

International participation

Lebanon participates in the international community through both international organizations and enacting international policy practices, such as the Sustainable development goals and the Paris Agreement.

Member organizations

ABEDA, ACCT, AFESD, AL, AMF, EBU, ESCWA, FAO, G24, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICC, ICRM, IDA, IDB, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, ILO, IMF, IMO, Inmarsat, ITUC, Intelsat, Interpol, IOC, ISO (correspondent), ITU, NAM, OAS (observer), OIC, PCA, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNHCR, UNIDO, UNRWA, UPU, WCO, WFTU, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO.

Sustainable development goals

Sustainable Development Goals and Lebanon explains major contributions launched in Lebanon towards the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals SDGs and the 2030 agenda.

Lebanon adopted the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015. It presented its first Voluntary National Review VNR in 2018 at the High Level Political Forum in New York. A national committee chaired by the Lebanese Prime Minister is leading the work on the SDGs in the country.[15] In 2019, Lebanon's overall performance in the SDG Index ranked 6th out of 21 countries in the Arab region.[16]

Multi-stakeholder forums were held by different UN agencies including the UN Global Compact Network in Lebanon during the late 2010s for the advancement of Global Goals and their Impact on Businesses in Lebanon. The latest two were held on October 18, 2018 and October 2019 under the title of connecting the global goals to Local Businesses.[17]See also

References

- ↑ "Pro-Western coalition declares victory in Lebanon – The Globe and Mail". Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ↑ solutions, EIU digital. "Democracy Index 2016 – The Economist Intelligence Unit". www.eiu.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ↑ Deeb, Marius (2013). Syria, Iran, and Hezbollah: The Unholy Alliance and Its War on Lebanon. Hoover Press. ISBN 9780817916664.

the Maronites and the Druze, who founded Lebanon in the early eighteenth century.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Liban : information sur l'âge de la majorité, en particulier chez les femmes; droits de garde du père sur les enfants de sexe féminin". Refworld. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ↑ "The anti-establishment - Executive Magazine". 13 September 2017. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ↑ "WAMU and Farid Abboud discuss Hariri's assassination". Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ↑ "Beirut explosion: Lebanon's government 'to resign' as death toll rises". BBC News. 10 August 2020.

- ↑ Chehayeb, Kareem. "After elections in Lebanon, does political change stand a chance?". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ Chehayeb, Kareem. "Hezbollah allies projected to suffer losses in Lebanon elections". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ Chehayeb, Kareem. "Hariri's absence leaves Sunni voters unsure ahead of Lebanon poll". www.aljazeera.com.

- ↑ Issam Michael Saliba (October 2007). "Lebanon: Presidential Election and the Conflicting Constitutional Interpretations". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "Caught between constitution and politics: the presidential vacuum in Lebanon". Heinrich Böll Stiftung Middle East. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 Ministry of Justice, Republic of Lebanon. "Judicial map". Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ↑ Department Of State. The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affairs. "Lebanon". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- ↑ "Lebanon .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Luomi, M.; Fuller, G.; Dahan, L.; Lisboa Båsund, K.; de la Mothe Karoubi, E.; Lafortune, G. (2019). Arab Region SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2019. SDG Centre of Excellence for the Arab Region/Emirates Diplomatic Academy and Sustainable Development Solutions Network. p. 5.

- ↑ Global Compact Network Lebanon (GCNL) (2015). "Our Mission".

External links

- Lebanon official government portal

- Lebanon Government at Curlie

- The Lebanese Politics Podcast