| This article is part of the series: Courts of England and Wales |

| Law of England and Wales |

|---|

_(2022).svg.png.webp) |

In England and Wales, magistrates (/ˈmædʒɪstrət/;[1] Welsh: ynad)[2] are trained volunteers, selected from the local community, who deal with a wide range of criminal and civil proceedings.[3] They are also known as Justices of the Peace.[3] In the adult criminal court, magistrates decide on offences which carry up to twelve months in prison, or an unlimited fine.[4] Magistrates also sit in the family court where they help resolve disputes that involve children, and in the youth court which deals with criminal matters involving young people aged 10-17.[5] Established over 650 years ago, the magistracy is a key part of the judiciary of England and Wales,[6] and it is a role underpinned by the principles of 'local justice' and 'justice by one's peers'.[6]

Magistrates typically sit as a bench of three,[7] mixed in gender, age and ethnicity where possible, to bring a broad experience of life to the bench. They can sit alone to hear warrant applications[8] or deal with uncontested matters heard under the single justice procedure.[9][10] All members of the bench have equal decision-making powers, but only the chairman, known as the Presiding Justice (PJ), speaks in court and presides over proceedings.[11] Magistrates are not required to have legal qualification; they are assisted in court by a legal adviser, who is a qualified solicitor or barrister, and who will ensure that the court is properly directed regarding the law.[12]

According to official statistics for diversity of the judiciary in 2021, 56% of sitting magistrates were women, 13% were Black, Asian and minority ethnic, and 82% aged above 50 as at 1 April 2021.[13] There were 12,651 magistrates in 2021, which has fallen steadily in recent years, decreasing by 50% from 25,170 since 2012.[13]

History of the magistracy

Magistrate derives from the Middle English word magistrat, denoting a "civil officer in charge of administrating laws" (c.1374); from the Old French magistrat; from the Latin magistratus, which derives from magister (master), from the root of magnus (great).[14] Today, in England and Wales, the word is used to describe a justice of the peace.

The office of justice of the peace has its origins in the 12th century when Richard I appointed 'keepers of the peace' in 1195.[15] The title justice of the peace derives from 1361, in the reign of Edward III. An Act of 1327 had referred to "good and lawful men" to be appointed in every county in the land to "guard the Peace". Justices of the peace still retain (and occasionally use) the power confirmed to them by the Justices of the Peace Act 1361 to bind over unruly persons "to be of good behaviour". The bind over is not a punishment, but a preventive measure, intended to ensure that a person guilty of a minor disturbance does not re-offend.[16] The Act provided, among other things, "That in every county of England shall be assigned for the keeping of the peace, one lord and with him three or four of the most worthy of the county, with some learned in the law, and they shall have the power to restrain the Offenders, Rioters, and all other Barators, and to pursue, arrest, take and chastise them according to their Trespass or Offence".[17]

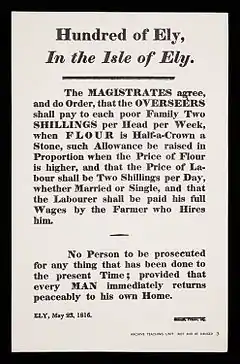

Over the following centuries, justices acquired many administrative duties, such as the administration of the Poor Laws, highways and bridges, and weights and measures. For example, before 1714, magistrates could be approached at any time and in any place by people legally recognised as paupers, appealing to them for aid if parish authorities had refused to provide any. It was relatively common for these magistrates to write out, on the spot, an Order requiring aid to be granted.[18] The 19th century saw elected local authorities taking over many of these duties. There is one remnant of these duties, the appellate jurisdiction over the licensing of pubs and clubs.

Towards the end of the 18th century, the absence of an adequate police force and the quality of local justices became matters of concern. Justices received no salary from the government, although they could charge fees for their services. They were appointed from prominent citizens of property, but a shortage of landed gentlemen willing to act in London led to problems. In Middlesex, for example, the commission was increasingly dominated by merchants, tradesmen and a small number of corrupt magistrates, known as "Trading Justices" because they exploited their office for financial purposes. A Police Bill in 1785 failed to bring adequate supervision of justices. However, the Middlesex Justices Act 1792 set up seven public offices, in addition to Bow Street, London, with three justices in each, with salaries of £400 a year. The power to take fees was removed from all justices in the city. Six constables were appointed to each office, with powers of arrest. This was the origin of the modern stipendiary magistrate (district judge).[19][20]

One famous magistrate was Sir John Fielding (known as the "Blind Beak of Bow Street"), who succeeded his half-brother as magistrate in Bow Street Magistrates' Court in 1754 and refined his small band of officers (formerly known as the Bow Street Runners) into an effective police force for the capital.[21] Stipendiaries remained in charge of the police until 1839.

The first paid magistrate outside London was appointed in 1813 in Manchester. The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 gave boroughs the ability to request the appointment of a stipendiary magistrate in their locality. Originally stipendiaries were not required to have any qualifications, however they could only be appointed from the ranks of barristers (from 1839) and solicitors (from 1849).[22] Women in England and Wales were not allowed to become justices until 1919, the first woman being Ada Summers, the Mayor of Stalybridge, who was a JP by virtue of her office.[23] In 2021, 56% of magistrates in England and Wales were female.[13]

Magistrates

The titles "magistrate" and "justice of the peace" are interchangeable terms for basically the same thing, although today the former is commonly used in the popular media, and the latter in more formal contexts.

Magistrates sit in tribunals or "benches" composed of no more than three members. Although three is the usual number, a bench is properly constituted with two members. However, if they sit as two on a trial and disagree about the verdict, a retrial will be necessary (see Bagg v Colquhoun (1904) 1KB 554).[24] Magistrates deal with around 97 per cent of criminal cases in England and Wales.[25] A single magistrate sitting solo can deal with remand applications, issue search warrants and warrants for arrest as well as conducting early administrative hearings. Since 2015, a single magistrate handles under the "single justice procedure" criminal cases where defendants plead guilty or do not respond to summons; 535,000 cases were heard this way in 2020.[26]

On a bench of two or three, the magistrate who speaks openly in court is formally known as the Presiding Justice,[27] or more informally as the chair, chairman or PJ. When sitting three magistrates on the bench, the chairman will sit in the middle. The magistrates sitting on either side of the chairman are known as "wingers". Magistrates deal with less serious criminal cases, such as common assault, minor theft, criminal damage, public disorder and motoring offences. They also send serious cases such as rape and murder to the Crown Court for trial, determine applications for bail, enforce the payment of fines, and grant search warrant and right of entry applications to utility companies (e.g. gas, electricity). Magistrates' powers are limited to a maximum sentence of twelve months imprisonment and/or an unlimited fine.[4] They also have a civil jurisdiction, in relation to family work, and the enforcement of child support and council tax payments.[28] To complement magistrates, there are a small number of district judges who are either barristers or solicitors. Under s 16(3) of the Justices of the Peace Act 1979 they have the same powers as magistrates but sit alone. Unlike judges in many of the higher courts, magistrates and district judges do not wear robes or wigs in the court room.

Lord Bingham, former Lord Chief Justice, observed that the lay magistracy was “...a democratic jewel beyond price".[29]

Qualifications

There are no statutory requirements as to the qualifications of a magistrate. There are, however, six core requirements as to the character of candidates for the magistracy, as laid down by the Lord Chancellor in 1998.[30] These are:

- Good character: Magistrates are expected to have personal integrity, enjoy the respect and trust of others, and be able to maintain confidences.

- Understanding and communication: Magistrates must be able to understand documents, identify and comprehend relevant facts reasonably quickly and follow evidence and arguments.

- Social awareness: Magistrates must have an appreciation of, and accept the need for, the rule of law in society. Magistrates should also display an understanding of their local communities, society in general, and have an understanding of the causes and effects of crime.

- Maturity and sound temperament: Magistrates must have the ability to relate to and work with others. They must have regard for the views of others and a willingness to consider advice.

- Sound judgement: Magistrates must have the ability to think logically, weigh arguments and reach a balanced decision. They must be objective and have the ability to recognize and set aside their prejudices.

- Commitment and reliability.: Magistrates must be committed to serving the community and be reliable.

Magistrates must be aged between 18 and 65 upon appointment,[31] with a statutory retirement age set at 75.[32] The minimum age of appointment was reduced from 27 to 18 in 2004.[33] However, appointments under the age of 30 are a rarity. In 2010 out of 30,000 magistrates in Wales and England only 145 were under the age of 30.[34]

Locality and commitment

Until the passage of the Courts Act 2003 it was necessary for magistrates to live within 15 miles of the commission area for the court in which they sat.[22] As a commission area was usually co-terminous with a county or metropolitan area, they could live a considerable distance from the court in which they sat. However, the Act introduced a single commission area for the whole of England and Wales. The country is divided into local justice areas and magistrates are expected to either live or work within reasonable travelling distance of their court.[35]

Magistrates must commit themselves to sitting for a minimum of 26 half days each year.[36] A 'half-day' sitting typically lasts from 10 am to 1 pm or from 2 pm to 5 pm, with new magistrates taking over the afternoon session. On other benches, sittings are organized with magistrates attending to sit for the whole day. Magistrates are expected to attend half an hour before sitting for preparation and a briefing about the case list from their legal adviser.[37]

Restrictions on appointment

Subject to the Lord Chancellor's discretion, a number of activities and occupations, including the occupations of a spouse or partner or other close relative, may give cause for concern in relation to the perceived impartiality of the bench and corresponding risk to the right to a fair trial.[38][39] For example, a candidate will not normally be eligible if:

- they are a member of the police service.[38]

- they are a member of, or have been selected (formally or informally) as a prospective candidate for election to, any parliament or assembly.[38]

- they are an undischarged bankrupt as it is unlikely that they would command the confidence of the public.[38]

- they are a probation officer

- they are a member of a Youth Offender Panel or Youth Offending Team

- they are a member of a Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnership

- they are a member of the Crown Prosecution Service

When considering candidates who have been subject to any order of a court (civil or criminal), various factors, including the nature and seriousness of the offence, will be considered before an appointment is made. Magistrates deal with motoring offences, and while minor motoring offences are not usually an issue, serious motoring offences, or persistent offending, might disqualify them. If they have had their licence suspended for less than twelve months in the past five years, or for twelve months or more in the past ten years, they will generally not be recommended for appointment.[38]

Members of the following professions are prohibited from serving as magistrates, but may have individual circumstances which means their employment is not incompatible with magistracy: Prison service employees; employees of the NSPCC; members of HM Armed Forces unless there is no realistic likelihood of a foreign posting; 'Mackenzie friends'; victim and witness support workers;

Members of the following professions are usually permitted to serve as magistrates, subject to certain exceptions depending on their individual circumstances or requirements not to sit in certain types of cases: Members of Local Authorities; Police employees two years after leaving police employment; traffic wardens; individuals connected to the police; Civil servants and employees of executive agencies; employees of local authorities; ministers of religion; social workers and care managers; educational welfare officers; licensees; bookmakers; members of prison Boards of Visitors and prison lay observers; employees of the Citizens Advice Bureau; members of Neighbourhood Watch Schemes; members of police authorities or probation boards; members of parole boards; members of crime prevention panels; interpreters; Sheriffs.

In any of the above cases, reference should be made to the Lord Chancellors directions and the Advisory Committees will make a determination in specific cases.[39]

District judges (magistrates' court)

Prior to 31 August 2000, district judges (magistrates' court) were known as stipendiary magistrates[40] (i.e. magistrates who received a stipend or payment). Unlike magistrates, district judges (magistrates' court) sit alone. Some district judges have been appointed from the ranks of legal advisers to the magistrates' court and will be qualified solicitors or barristers. Questions have been raised by the Magistrates' Association as to the legal safeguards of a single district judge being allowed to hear a case, decide the outcome and pass sentence without reference to another tribunal member,[41].

Originally, deputy district judges could only be drawn from barristers and solicitors of at least seven years' standing. However, in 2004, calls for increased diversity among the judiciary were recognized and the qualification period was changed[42][43] so that, as of 21 July 2008, a potential deputy district judge can satisfy the judicial-appointment eligibility condition on a five-year basis.[44] and so that other types of lawyer, such as legal executives (ILEX Fellows), would also be eligible.[45]

Appointment

In the year to 31 March 2020, 1,011 Magistrates were appointed to and 1,440 Magistrates left the position.[46]

The appointments are made by the Senior Presiding Judge on behalf of the Lord Chief Justice.[47]

Local advisory committees

These committees are responsible for selecting suitable candidates for the magistracy. They comprise a maximum of twelve magistrate and non-magistrate members. The membership of local advisory committees used to be confidential but following reform in 1993 all names must be published.

Local advisory committees have regard to the composition of local benches, especially the numbers needed to process the work, and the balance of gender, ethnic status, geographical spread, occupation, age and social background.[48] Anyone who meets the basic requirements can put themselves forward as a candidate for the magistracy. In fact, many local committees advertise for candidates, mounting campaigns to attract a diverse range of people. Advertisements are placed in local papers, newspapers, magazines aimed at ethnic groups, or even on buses. In Leeds for example, committees have used the radio to invite potential candidates to attend their local magistrates' court open evening.[49]

Interview panels

Upon appointment, a new magistrate will be required to swear or affirm an oath that they "will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, her heirs and successors, according to law" and that they "will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth the Second in the office of Justice of the Peace, and will do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm without fear or favour, affection or ill will"...

— SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE[50]

The first stage of the selection process is the submission of a detailed application form, from which potential magistrates are first sifted to check eligibility to apply and basic suitability. Then, those who are eligible, will be invited to a first interview where selectors from the local advisory committee will seek to establish more about the candidates' personal qualities and whether or not they possess the six key qualities required. The interviewers also use the opportunity to explore the candidates' attitudes on various criminal justice issues such drink driving, juvenile crime or vandalism.[51] If successful at the first interview, the candidate will be invited to a second interview where they will discuss some practical examples of the type of cases with which magistrates deal. Typically, this will involve a discussion of at least two case studies which are typical of a magistrates' court. In both interviews the candidate will be assessed against the core competencies.[52][53] This is designed to assess and explore the potential candidates' judicial aptitude.[48][51]

Following the interview stage, the committee will submit the names of those who they assess as being suitable for appointment, to the Lord Chancellor, to fill the available vacancies. By the Constitutional Reform Act 2005, interim arrangements mean that recommendations are passed to the Lord Chief Justice for approval, before being submitted to the Lord Chancellor to make the appointment from the list on behalf of, and in the name of, the King.[54]

Magistrates' duties

A magistrate primarily deals with criminal cases, although they have a civil jurisdiction and can also choose to specialise in the family proceedings court. The civil cases they deal with include issuing warrants of entry to the utility companies (gas, water and electricity), enforcing payment of council tax, as well as appeals from local authority licensing decisions regarding pubs and clubs.[55] All criminal cases start in the magistrates' courts, and 97 per cent are concluded there.

There are three types of criminal offence:

- summary offences – such as most motoring offences, less serious assaults and many public order offences, which can only be dealt with in the magistrates' courts. For these offences, magistrates will decide bail (in the more serious cases), taking a plea – guilty or not guilty – deciding verdict and passing sentence.

- triable either-way offences – such as theft, fraud, criminal damage (value of damage over £5,000), assault occasioning actual bodily harm, some less serious sexual offences, dangerous driving. In these cases, magistrates decide venue (magistrates' court or Crown Court) after hearing representations from the prosecution and defence. If they decide on trial in the magistrates' court, the defendant can still elect trial at the Crown Court. Otherwise, magistrates will have the same powers as summary offences – dealing with bail, passing sentence, etc.

- indictable-only offences – these are the most serious cases such as murder, rape and robbery, which can only be dealt with by trial on indictment at the Crown Court. Nevertheless, the first hearing of such cases is in the magistrates' court where the bench considers bail and then sends the case to the Crown Court.[56][57]

Single magistrates do not normally hear cases on their own, although they do have a limited jurisdiction. They usually sit as one of a bench of three magistrates, together with a qualified legal adviser who can advise them on matters of law and procedure.[58]

Youth & family proceedings courts

For young offenders aged between 10 and 17 years, there are special arrangements. Youth courts are set apart from the adult courts and the procedures are adapted to meet the different needs of younger persons, for example by requiring the attendance of parents and ensuring that everything is explained in appropriate language. Members of the public are generally excluded from the youth and family proceedings courts and, although the press may attend, there are restrictions on what they can report. Magistrates sitting on the youth court are members of youth panels which meet regularly for training and administrative purposes. Youth magistrates receive specialist training in the youth court, and are mentored and appraised in that role. A youth court must usually include one male and one female member.[59]

Likewise, there is also a special panel for the family proceedings court which deal with private and public family cases. These include applications for non-molestation orders, occupation orders, adoption orders, maintenance cases, and proceedings under the Children Act 1989.[60][61]

Magistrates also sit at the Crown Court to hear appeals against verdict and/or sentence from the magistrates' court. In these cases the magistrates form a panel with a judge.[60] A magistrate is not allowed to sit in the Crown Court on the hearing of an appeal in a matter on which they adjudicated in the magistrates' court. There is a right of appeal from magistrates' decisions on points of law to the Queen's Bench Divisional Court.[57]

Training of magistrates

Section 19(3) of the Courts Act 2003 states that the Lord Chief Justice must provide training for magistrates. In practice this is delivered by the Judicial College (formerly the Judicial Studies Board) and follows the National Training Programme for Magistrates which aims to support the learning and development of magistrates to a consistent standard across England and Wales.[62]

The initial classroom-based induction training takes place over a minimum of 3 days, and must be completed before a magistrate can be appointed. The training includes topics such as judicial awareness, trial procedure, structured approaches to verdict and sentence, common sentencing options, a particular focus on the sentencing of traffic offences, bail and case management.[63] Twelve months after appointment, magistrates are required to attend a further consolidation training which aims to reflect and build on their experience and competence as a magistrate.[64] All magistrates are required to visit a prison establishment, a young offenders institution and a probation service facility, and are required to have observed the court on at least three occasions prior to the completion of their initial training.[65]

Further essential training is delivered regularly by the Judicial College, to ensure that magistrates remain competent and confident in performing their role.[65] Essential training is identified and agreed by the magisterial criminal and family subcommittees of the Judicial College, however local Training, Approvals, Authorisations and Appraisals Committees (TAAACs) may also identify specific local training needs that are dealt with at a local level.[66] A compulsory "first continuation" training takes place for all magistrates who have been sitting for at least three years, and who were deemed competent at their threshold appraisal.[67]

The National Training Programme aims to encourage a culture of continuous professional development, which is supported by a programme of training, mentorship, self-assessment, objective assessment via appraisal, and regular post-court reviews.[62]

Mentors

All new magistrates are provided a personal development log and are allocated a mentor,[68] an experienced magistrate who has been specially trained to take on this role. The mentor will advise, support, and guide the magistrates, particularly during the first few months. A new magistrate will have a minimum of six formal sittings attended by their mentor, each of which is followed by an opportunity to discuss the days business and help to consolidate and apply their initial training. The magistrate will reflect on how they have applied the knowledge and skills developed during their initial training and, using the competence framework, will consider whether or not they have any further training and development needs.[69]

Appraisal

A threshold appraisal takes place after one year of sitting as a magistrate.[65] This is conducted by an appraiser who is an experienced magistrate specially trained for the role. Following the sitting, the magistrate and the appraiser use the competence framework for magistrates to assess the appraisee's performance and to identify if the magistrate has any outstanding training needs. All magistrates are appraised every four years in each of the judicial roles they perform, except for Presiding Justices, who are appraised every 2 years.[65] If extra training is given and the magistrate cannot demonstrate that they have achieved the necessary competency level, the matter is referred to the local advisory committee, who may recommend to the Lord Chancellor that the magistrate is removed.[68]

Training for additional roles

Experienced magistrates may choose to take on additional roles and responsibilities, such as becoming a Presiding Justice, sitting in the family or youth courts or becoming an appraiser or mentor. Requirements for authorisation in these roles depend on having acquired the pre-requisite experience and having been deemed competent in their last appraisal. There is additional compulsory training required for these roles, which is delivered by the Judicial College.[70]

Retirement and removal

Retirement

The statutory retirement age for magistrates is 75 years. The retirement age was, until 2021, 70, but any magistrates who had to retire at 70 and who are still under 75 may apply for reinstatement if they wish. When magistrates reach retirement age, their names are placed on the Supplemental List. Although they can no longer sit as magistrates, they are able to carry out minor administrative functions, the signing of official documents. Magistrates may of course resign their office at any time. Magistrates moving out of the judicial area are placed on the Supplemental List until there is a vacancy in the new area.[71]

Removal

According to Section 11 of the Courts Act 2003[72] and Section 314 of The Constitutional Reform Act 2005,[73] the Lord Chancellor with the concurrence of The Lord Chief Justice has the statutory power to remove a magistrate for the following reasons:

- On a finding of incapacity or misbehaviour[74]

- On the ground of a persistent failure to meet such standards of competence as are prescribed by the Lord Chancellor or

- If the Lord Chancellor is satisfied that the magistrate is declining or neglecting to take a proper part in the exercise of judicial functions.

The record for the most removals of magistrates came under the Chancellorship of Lord Irvine who dismissed fifteen magistrates in 1999.[75] The Lord Chancellor's office has been criticised in the past for the dismissal of a JP who was taking part in a CND march and a JP who engaged in transvestite behaviour.[76]

The justices' clerk

The principal adviser to a bench or benches of magistrates is the justices' clerk, appointed under the Courts Act 2003 by the Lord Chancellor. The justices' clerk will be a qualified solicitor or barrister of at least five years' standing. The vast majority of magistrates' courts are taken by the justices' clerk's assistants who are known as magistrates' clerks, court clerks or legal advisers. Their primary role is to provide legal advice to magistrates in the court room and in their retiring room, as well as assisting in the administration of the court business.[76] The clerk's duty is to guide magistrates on questions of law, practice and procedure. This is set out in the Justices of the Peace Act (1979) s 28(3) which provides:

It is hereby declared that the functions of a justices' clerk include the giving to the justices to whom he is clerk or any of them, at the request of the justices or justice, of advice about law, practice or procedure on questions arising in connection with the discharge of their or his functions, including questions arising when the clerk is not personally attending on the justices or justice, and that the clerk may, at any time when he thinks he should do so, bring to the attention of the justices or justice any point of law, practice or procedure that is or may be involved in any question so arising.[77]

Although the clerk can assist the magistrates in their decision-making (e.g. advising on the sentencing guidelines of higher courts, or on the admissibility of evidence), he/she should not participate in the factual decision-making process. Neither should he/she automatically accompany the magistrates when they retire to make their decisions, although they can be invited to join them. This principle has been upheld in case law, such as the case of R v Eccles Justices, ex parte Farrelly (1992) in which the Queen's Bench Divisional Court quashed convictions because a court clerk had apparently participated in the decision making process.

A justices' clerk has the powers of a single magistrate, for example to issue a summons, adjourn proceedings, extend bail, issue a warrant for failing to surrender to bail where there is no objection on behalf of the accused, dismiss an information where no evidence is offered, request a pre-sentence report, commit a defendant for trial without consideration of the evidence and make directions in criminal and family proceedings.[78] The justices' clerk may delegate these functions to a legal adviser (referred to as "assistant justices' clerk" in the relevant legislation).[79] The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 also gives clerks the powers to deal with early administrative hearings.[80]

Evaluations of magistrates

Over the last fifteen years, there have been a number of research papers and reviews of the role of magistrates, with many observations being made:

Composition of the bench

Magistrates have been perceived as middle-class, middle-aged and middle-minded and this has some foundation in fact.[81] The Judiciary in the Magistrates' Court (2000) report found that magistrates were overwhelmingly from professional and managerial backgrounds and 40 per cent of them were retired from full-time employment.[81] The majority of magistrates are within the 45–65 age range and the appointment of magistrates under the age of 30 is still rare although there are a few notable exceptions. For example, in 2006 a 19-year-old law student, Lucy Tate, was appointed making her Britain's youngest magistrate.[82]

The majority (56%) of magistrates are female. This compares to 32% of professional judges.[83]

Ethnic minorities are reasonably well represented. According to The National Strategy for the Recruitment of Lay Magistrates (2003), 6 per cent of magistrates are of an ethnic minority background which is close to the 7.9 per cent of the population as a whole. Again this compares favourably with the professional judiciary which only has 1 per cent membership from ethnic minorities.[52] This comparatively high level of ethnic minorities in the magistracy is largely a result of campaigns to attract a wider range of candidates, such as that launched by the Lord Chancellor's Department in March 1999. In announcing the campaign Lord Irvine stated:

Magistrates come from a wide range of backgrounds and occupations. We have magistrates who are dinner-ladies and scientists, bus drivers and teachers, plumbers and housewives. They have different faiths and come from different ethnic backgrounds, some have disabilities. All are serving their communities, ensuring that local justice is dispensed by local people. the magistracy should reflect the diversity of the community it serves.[84]

Typical recruitment campaigns have been supported by local newspapers and magazines. In efforts to target minorities adverts are placed in publications such as Caribbean Times, the Asian Times and Muslim News.[85] The Lord Chancellor also encouraged disabled people to apply and this has resulted in the appointment of a blind magistrate.[86]

The narrowness of magistrates' backgrounds has been blamed on the selection process with magistrates on the advisory committee tending to appoint people from similar backgrounds to themselves. However, this criticism has been ameliorated to some extent by the widening of advisory committee membership to include non-magistrates.[52][87]

The Auld Report (2001) commented that it was unrealistic to expect the social composition of magistrates to be close to that of the general population.[88] This was partly because many people found it difficult to obtain support from their senior managers to be released for magisterial duties, and because of other reasons relating to employment. Therefore, the bench would never be a true cross-section of society.

Government figures published in 1995 showed a Conservative Party bias among magistrates, although the significance of this finding is inconclusive.[87] A 1979 study found that there was no appreciable difference in approach between the different classes, but that Conservative magistrates tend to express a harder attitude on sentencing. However, it was not established whether this attitude was reflected in their sentencing decisions.[87] In 1997, the Labour Lord Chancellor, Lord Irvine, called for more Labour magistrates to be appointed.[89] The Labour Government later concluded that it was no longer necessary to seek a political balance on benches because people no longer voted along class lines. A 1998 White Paper stated: "Perhaps most importantly, political balance, as this consultation paper attempts to show, no longer acts as a guarantor or viable proxy for someone's position in society. Historically voting was class based, but, it is argued, this is no longer the case."[90]

The term "bench" is also used collectively to describe a group of magistrates assigned to a particular local justice area, for example "The Midshire Bench".[91]

Public confidence

In their report, Professor Rod Morgan and Neil Russell demonstrated that there was lack of public understanding about magistrates: 33% of the public thought that magistrates were legally qualified.[81] Professor Andrew Sanders (Sanders 2001) found a low level of public confidence in magistrates' courts based on a British Crime Survey, a MORI poll and focus groups with the public and with offenders. Lord Justice Auld was scathing about these aspects of the research, stating in his report that "it is one thing to rely on uninformed views of the public as a guide to what may be necessary to engender public confidence, and another to rely on such views as an argument for fashioning the system to meet them. Public confidence is not an end in itself; it is or should be an outcome of a fair and efficient system. The proper approach is to make the system fair and efficient and, if public ignorance stands in the way of public confidence, take steps adequately to demonstrate to the public that it is so."[92]

A number of initiatives have been formulated to improve community relations: "Magistrates in the Community" which deals with public relations at a local level, such as presentations to schools, colleges and community groups; the National Magistrates' Mock Trial Competition run in conjunction with the Citizenship Foundation which involves schoolchildren in mock trial competitions; the Local Crime and Community Sentence project. Court open days organised by Her Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service are another method of engaging with the community.[93] Projects are in place to improve public confidence in the criminal justice system (CJS) as a whole. The British Crime Survey of September 2010 reported that 61 per cent of adults thought that the CJS was fair and 42 per cent thought that the CJS was effective.[94]

The importance of local knowledge

The Auld report noted that local justice was seen as "a bridge between the public and the court system which might otherwise appear remote". However, locality could encourage inconsistencies between areas and created a risk of magistrates knowing defendants too well.[92] The argument that magistrates should have a good knowledge of their local justice area is still raised today, often as a defence to court closures.[95][96] The idea that magistrates should be "local" derives from the fact that magistrates are drawn from that area and, until the Courts Act 2003, had to live within 15 miles of their commission area. In reality, magistrates may not have a knowledge and understanding of their area, especially the poorer parts, because most of them come from professional and managerial classes and live in affluent areas. Nevertheless, it is suggested they are likely to have a greater awareness of local events, local patterns of crime and local opinions than a professional judge from another area.

In the case of Paul v DPP (1989), the court had to decide whether a kerb crawler was 'likely to cause a nuisance to other persons in the neighbourhood'. The defendant was convicted on the basis that the magistrates knew that kerb crawling was a problem in that residential area.[97] On appeal Lord Justice Woolf noted that this was a case where magistrates' local knowledge had been useful.

Cost and timeliness

The use of unpaid magistrates is cost effective, in terms of cost and timeliness, saving the tax payer from the high cost of employing full-time judges. The report The Judiciary in the Magistrates' Court (2000) found that at the time the cost of using lay magistrates was £52.10 per hour compared with the cost of using a stipendiary at £61.90 an hour.[88] In 2010, offence-to-completion time for defendants whose case was committed or sent for trial at the Crown Court was an average of 187 days. The estimated average offence-to-completion time in the magistrates' courts for indictable/triable either-way offences was 109 days for the same period.[98] The cost of a trial in the magistrates' court is also much cheaper than the cost in the Crown Court both for the government and for those defendants who pay their own legal costs. However, it should remembered that the Crown Court generally deals with more complex and lengthy cases than the magistrates' court.

Legal adviser

The issue of the legal qualifications of legal advisers has come under scrutiny in recent years.

Following reforms in 1999, all legal advisers were required to be legally qualified.[99] Any existing legal advisers under the age of 40 in 1999 were required to gain a legal qualification within 10 years. The Assistants to Justices' Clerks Regulations 2006,[100] in regulation 3, set out the qualifications for assistants to justices' clerks who could be employed as clerks in court. They provided that people who have qualified as barristers or solicitors and had passed the exams for either of those professions or had been granted an exemption were qualified to be assistants to justices' clerks which meant that they can carry out matters on behalf of the justices' clerk. The 2006 Regulations also enabled the Lord Chancellor to make temporary appointments of people to act as clerks in court where he was satisfied that they were, in the circumstances, suitable and that no other arrangement can reasonably be made.

However, the Assistants to Justices' Clerks (Amendment) Regulations 2007[101] replaced regulation 3 of the 2006 Regulations. The effect was to clarify that those: (i) who were in employment as an assistant registered by the Law Society under regulation 23 of the Training Regulations 1990 (ii) who held a valid training certificate granted by a magistrates' courts committee before 1 January 1999; or (iii) who acted as a clerk in court before 1 January 1999 and were qualified to act as such under the justices' clerk (Qualification of Assistants) Rules 1979 (as amended) to carry out the duties of assistant clerks could act as clerks in court.

These changes have brought a greater degree of professionalism to magistrates' courts, thus helping magistrates in dealing with points of law and procedure. Furthermore, the training of magistrates has become more consistent with the involvement of the Judicial Studies Board.

Few appeals

Comparatively few appeals are made against decisions made by the magistrates' court, and the majority are made against sentence rather than verdict. The Judicial Statistics Annual Report (2006) showed that only 12,992 appeals were made to the Crown Court from the magistrates' court. Of these only 2,020 were allowed and 3,184 resulted in a variation of sentence, out of a total of 2 million defendants dealt with in the magistrates' court.[102] There are also very few appeals allowed because an error of law was made. This is shown by the fact that only 100 appeals were allowed by way of case stated to the Queen's Bench Divisional Court, of these only 42 were allowed. In 2008, there were only 72 appeals, on a point of law, to the Queen's Bench Division, of which 30 were allowed.

Obliged to give reasons

The Human Rights Act 1998 imported the European Convention on Human Rights into English law. Article 6 of the convention gives an accused the right to a fair trial. Implicit in this right is the requirement that magistrates give reasons for their decisions, unlike jury verdicts in the Crown Court.[103]

Prosecution bias

One criticism of magistrates' courts is that they have high conviction rates in comparison to jury trials in the Crown Court because, it is suggested, magistrates have a bias in favour of the prosecution.[104] Unsurprisingly, in a 1982 study commissioned by the Home Office, it was found that direct evidence from prosecution witnesses whose credibility was not challenged led to a high level of convictions. Weaknesses in the prosecution case, such as unreliable witness evidence, a lack of confessions or direct evidence against the defendant led to higher likelihood of acquittal. However, in those cases where a defendant's credibility was not demonstrably undermined, there was a conviction rate of 63 per cent. In the majority of these cases, there was first-hand evidence (mainly from police witnesses) of the defendant's behaviour from which criminal intent was inferred.[105]

Since the inauguration of the Crown Prosecution Service in 1986, the proportion of weaker prosecution cases has declined as a result of the CPS' review function which requires a "realistic prospect of conviction" before a prosecution can be commenced or continued.[106][107] In 2009, the conviction rate of defendants tried in magistrates' courts for all offences was 98% and in the Crown Court, 80%.[108][109]

One contributor to Lord Justice Auld's Review of the Criminal Courts of England and Wales (2001) drew attention to the "dichotomy in people's attitudes towards the magistracy, according to whether they are considering the elective right to trial by jury in 'either-way' cases or the relative advantages of lay and professional judges in summary cases. On the former issue magistrates are often portrayed as part of the establishment, being used to deny defendants a basic human right; on the latter they are depicted as the near equivalent of a jury – the peers of people who appear before them, ordinary people with experience of the real world, bringing common sense to bear etc."[88][92]

The need for magistrates to demonstrate impartiality in criminal trials was emphasised in the case of Bingham Justices ex p Jowitt (1974). A motorist was charged with exceeding the speed limit and the only evidence was contradictory, in the form of the statements of the defendant and a police officer. The defendant was found guilty and the chairman stated "My principle in such cases has always been to believe the police officer". The conviction was quashed on appeal as the magistrates clearly demonstrated bias.[110]

Inconsistency in sentencing

It has been demonstrated that magistrates in different regions have passed different sentences for what appear to be similar offences. The Government's White Paper, Justice for All set out differences found in criminal sentencing in the magistrates' court.[88][111]

- For burglary of dwellings in Teesside, 20 per cent of offenders were sentenced to an immediate custodial sentence, compared with 41 per cent in Birmingham; 38 per cent of burglars in Cardiff Magistrates' Court received community sentences compared with 66 per cent in Leicester.

- For driving while disqualified, the percentage of offenders sentenced to custody ranged from 21 per cent in Neath Port Talbot (South Wales) to 77 per cent in Mid-North Essex.

- For receiving stolen goods, 3.5 per cent of offenders sentenced in Reading Magistrates' Court received custodial sentences, compared with 48 per cent in Greenwich and Woolwich and 39 per cent in Camberwell Green.

Statistics published in 2004 showed no improvement. For example, magistrates in Sunderland discharged 36.4 per cent of all defendants, compared with 9.2 per cent in Birmingham. In Newcastle, magistrates sentenced only 7.2 per cent to an immediate custodial sentence, whereas in Hillingdon this figure was 32 per cent.[112]

The Prison Reform Trust Report on Sentencing (2009–2010) highlighted a number of issues including the following:

- Youth courts in Merthyr Tydfil issued custodial terms for just over 20 per cent of all sentences over the period, the highest in England and Wales, and ten times the equivalent rate in Newcastle.

- Case hardening: It can be argued magistrates are susceptible to finding over time that circumstances are not shocking and passing sentences becomes less of a big issue so leading to a more cynical approach.[111]

However, when the statistics are put in context, they may not appear as severe as they might at first glance. Only 4 per cent of offenders dealt with by magistrates receive a prison sentence. Furthermore, in an effort to bring a greater degree of consistency to sentencing, national guidelines have been issued to magistrates and updated on a regular basis. These "Sentencing Guidelines" are issued under the aegis of the Sentencing Council which aims to improve sentencing practice in the criminal courts.[113]

Reliance on the legal adviser

The lack of legal knowledge of magistrates should be offset by the fact that a legally qualified clerk is available. It is suggested that, in some courts, magistrates place too much reliance on the clerk, to the extent that a few cases have been quashed on appeal. For example, in R v Birmingham Magistrates ex parte Ahmed [1995], the defendant was accused of deception and handling. When the magistrates retired to consider their verdict, the clerk joined them. Since there was no point of law arising, this created a suspicion that he was taking part in deciding the verdict, and therefore the verdict was quashed. In the case of R v Eccles Justices, ex parte Farrelly (1992) the Queen's Bench Divisional Court quashed convictions because the clerk had apparently assisted and participated in the decision making process. In R v Sussex Justices, ex parte McCarthy (1924), a motorcyclist was involved in a road accident which resulted in his prosecution before a magistrates' court for dangerous driving. Unknown to the defendant and his solicitor, the clerk was a member of the firm of solicitors acting in a civil claim against the defendant arising out of the accident that had given rise to the prosecution. The clerk retired with the magistrates, who returned to convict the defendant. On learning of the clerk's provenance, the defendant applied to have the conviction quashed. The magistrates swore affidavits stating that they had reached their decision to convict the defendant without consulting their clerk.[114]

Magistrates' Association

The Magistrates' Association is the membership organisation for magistrates. Since 1969, it has helped to develop various sentencing guidelines. It also organises conferences and publishes a journal, The Magistrate, ten times a year. Members also participate in local branch activities, with each branch nominating representatives to the organisation's council.

See also

- Lay judge

- Magistrates' Courts Act 1980

- Courts of England and Wales

- Judicial titles in England and Wales

- Judiciary of the United Kingdom

- Justice of the peace court (Scottish equivalent of a Magistrates' Court)

References

- ↑ "Definition of MAGISTRATE". www.merriam-webster.com. 30 November 2023.

- ↑ "Recriwtio Ynadon – Just another Justice On The Web site".

- 1 2 "Magistrates Association > About magistrates". www.magistrates-association.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- 1 2 "Magistrates' Court". www.judiciary.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Magistrates Association > About magistrates > Jurisdiction > Youth court". www.magistrates-association.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- 1 2 "The role of the magistracy". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Criminal courts". GOV.UK. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ Search Warrants. Crown copyright. 2020. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-5286-2169-4.

- ↑ "Single Justice Procedure Notice (SJPN)". www.singlejusticeprocedure.co.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Bench Chair". www.judiciary.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Magistrates Association > About magistrates". www.magistrates-association.org.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Diversity of the judiciary: Legal professions, new appointments and current post-holders – 2021 Statistics". GOV.UK. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "magistrate". etymonline.com/. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ English legal system, 2011–2012. London: Routledge. 2011. p. 237. ISBN 978-0-415-60007-1.

- ↑ "The History of Justices of the Peace". lowestoftheritage.org. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "Justices of the Peace Act 1361".

- ↑ Rees, Rosemary (2001). Poverty and public health, 1815–1948 (null ed.). Oxford: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32715-6.

- ↑ "Justices of the Peace and the Pre-Trial Process". London Lives – 1690 to 1800. londonlives.org. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ Skyrme, Thomas Sir (1991), History of the Justices of the Peace, Chichester, England: Barry Rose, ISBN 1-872328-45-8, OL 1298084M, 1872328458

- ↑ The Times, 31 July 2005, "Bow Street hits the end of the road": http://www.timesonline.co.uk/newspaper/0,,176-1714810,00.html

- 1 2 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Oh, That Glass Ceiling ... More of a Bar than a Gate". Criminal Law and Justice Weekly. criminallawandjustice.co.uk/. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ Stone's Justices' Manual (Stones Justices' Manual (Stone's Justices' Manual) ed.), Butterworths Law, 30 April 1997, ISBN 978-0-406-99595-7, OCLC 60157302, OL 10182118M, 0406995958

- ↑ "Volunteering as a magistrate". Direct Gov. direct.gov.uk/. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Explaining the Single Justice Procedure in the magistrates' court - Inside HMCTS". insidehmcts.blog.gov.uk. 26 October 2021.

- ↑ "Glossary". Magistrates Association.

- ↑ "Magistrates". The Judiciary of England and Wales. judiciary.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Phillips, Andrew (2 December 2001). "We must hold on to local justice". The Guardian, A Phillips. London: theguardian.com/. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "Part 2 – Eligibility, Section 2 – Key Qualities, Pages (24–26)" (PDF). Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State's Directions for Advisory Committees on Justices of the Peace. judiciary.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "APPLICATION FORM GUIDANCE NOTES" (PDF). direct.gov.uk/. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Part 2 – Eligibility, Section 3 – Personal factors, (Page 26)" (PDF). Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State's Directions for Advisory Committees on Justices of the Peace. judiciary.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Controversy flares over magistrate aged 19". Yyorkshire Post. yorkshirepost.co.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Student becomes youngest magistrate in Wales". BBC News. news.bbc.co.uk. 6 January 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Courts Act 20032003 c. 39Part 2 The commission of the peace and local justice areas". Courts Act 2003. legislation.gov.uk/. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Part 2 – Eligibility, Section 2 – Key Qualities, Commitment and reliability, Page 26" (PDF). Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State's Directions for Advisory Committees on Justices of the Peace. judiciary.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "2. CONDITIONS OF SERVICE Page 6" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – a detailed guide to the role of JP. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – - a detailed guide to the role of JP" (PDF). direct.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Part 2: Eligibility, Section 4 – Activities and occupations which affect eligibility, Page 29" (PDF). Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State's Directions for Advisory Committees on Justices of the Peace. judiciary.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "Judiciary of England and Wales". Gender Statistics. judiciary.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ John Thornhill, Chairman of the Magistrates Association – Solicitors Journal – April 2011

- ↑ "Increasing Diversity in the Judiciary". Department for Constitutional Affairs. October 2004. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

CP 25/04

- ↑ "Explanatory Notes to Tribunals, Courts And Enforcement Act 2007". Office of Public Service Information. 2007. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2008.

paras.281–316

- ↑ Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, s.50/ Sch.10, Pt.1.13

- ↑ "Legal Executives as Judges". ilex. ilex.org.uk/. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "Diversity of the judiciary 2020 statistics: data tables, Worksheet 3.5 JO Magistrates". Diversity of the judiciary 2020 statistics. Ministry of Justice.

- ↑ "Becoming a magistrate in England and Wales: guidance". Ministry of Justice.

- 1 2 "Magistrates". The Judiciary of England and Wales. judiciary.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – - a detailed guide to the role of JP (Page 17)" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 "Part 3 – The Selection Process, Section 5 – Interviews, (Page 44 – 47)" (PDF). Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State's Directions for Advisory Committees on Justices of the Peace. judiciary.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE - - a detailed guide to the role of JP (Page 17, right side)" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE, 5. YOUR SELECTION Page 16" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – a detailed guide to the role of JP. direct.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE,- a detailed guide to the role of JP Page 3" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE,- a detailed guide to the role of JP. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 Christopher J. Emmins (1985), A practical approach to criminal procedure, London: Financial Training, ISBN 0-906322-77-4, OL 22828395M, 0906322774

- ↑ Reporting restrictions in the Magistrates' Court (PDF). Judicial Studies Board.

- ↑ "SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE, Page 6" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – a detailed guide to the role of JP. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Children Act 1989". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- 1 2 National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019. p. 3.

- ↑ National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019. pp. 9–10.

- ↑ National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019. p. 11.

- 1 2 3 4 "Magistrates Association > About magistrates > Training of magistrates". www.magistrates-association.org.uk. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019. p. 4.

- ↑ National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019. p. 12.

- 1 2 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "MENTORING Page 14" (PDF). SERVING AS A MAGISTRATE – a detailed guide to the role of JP. direct.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ National Training Programme for Magistrates. Judicial College. 2019.

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline (2008). Chris Martin (ed.). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

- ↑ "Courts Act 2003 c. 39 Part 2 Lay justices Section 11". Courts Act 2003. legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "Constitutional Reform Act 2005 c. 4 SCHEDULE 4 Part 1 Courts Act 2003 (c. 39) Section 314". Constitutional Reform Act 2005. legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. pp. 1 39. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Verkaik, Robert (6 July 2000). "Magistrate sackings on rise under Lord Irvine". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- 1 2 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Justices of the Peace Act 1979" (PDF). legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ "The Justices' Clerks Rules 2005".

- ↑ The Role of the Justices' Clerk and the Legal Adviser, Justices' Clerks' Society, December 2008.

- ↑ "Crime and Disorder Act 1998". legislation.gov.uk/. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Morgan, R; Russell, N. "The Judiciary in the Magistrates' Courts – Morgan, R & Russell, N" (PDF). The Judiciary in the Magistrates' Courts. library.npia.police.uk/. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ↑ Helen Carter (11 September 2006). "Law student, 19, becomes youngest magistrate". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ "Judiciary Diversity Statistics 2019" (PDF).

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Garry Slapper; David Kelly (2011). English legal system, 2011–2012 (null ed.). London: Routledge. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-415-60007-1.

- ↑ Born, Matt (26 June 2001). "Lord Chancellor lifts ban on blind magistrates". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Elliott, Quinn (2007). English Legal System. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-1-4058-4733-9.

- 1 2 3 4 "Justice for All" (PDF). cps.gov.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ Gibb, Frances (13 October 1997). "Lord Irvine attacked over call for more Labour JPs". The Times. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ Political Balance in the Lay Magistracy A Lord Chancellor's Department Consultation Paper. London: Lord Chancellor's Department. 1998. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "What is a bench of magistrates?". Law-glossary.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Magistrates". A Review of the Criminal Courts of England and Wales. criminal-courts-review.org.uk. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "Magistrates in the Community". Magistrates' Association. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "Experience of the Criminal Justice System for victims and witnesses" (PDF). British Crime Survey. Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ "Oxfordshire Magistrate Warns of Court Closure", BBC News Oxford, BBC, 16 June 2011, retrieved 18 June 2011

- ↑ "Bids to Save Magistrates' Courts in Kent and Wales Rejected", BBC News Kent, BBC, 16 June 2011, retrieved 18 June 2011

- ↑ "Vollans & Asquith: English Legal System Concentrate". oup.com/uk/. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "Time intervals for Criminal Proceedings in Magistrates' Courts". Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ↑ Justices' Clerks (Qualification of Assistants) Rules 1979 (SI 1979/570) as amended by S.I. 1998/3107, 1999/2814, and 2001/2269.

- ↑ "Assistants to Justices' Clerks Regulations 2006". Statutory Instruments. legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Justices' Clerks (Amendment) Regulations 2007". Statutory Instruments. legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "Judicial and Court Statistics 2006" (PDF). official-documents.gov.uk/. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ↑ "Human Rights Act 1998". legislation.gov.uk/. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Contested Trials in Magistrates' Courts". Home Office. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Code for Crown Prosecutors (PDF). London: CPS. 2010. p. 28.

- ↑ "HM Chief Inspector of the Crown Prosecution Service Annual Report 2010-2011" (PDF). HMCPSI. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "History of the CPS". CPS. cps.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "What is the conviction rate at court?" (PDF). Key Facts and Figures from the Criminal Justice System 2009/2010. Matrix Evidence Ltd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ↑ "English Legal Systems 1 & 2" (PDF). Module Manual – Undergraduate L1 2010/2011 For LLB Students. brad.ac.uk/. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- 1 2 Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS. London: Hodder Arnold. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Turner, Jacqueline Martin; editor, Chris (2008). OCR Law for AS (null ed.). London: Hodder Arnold. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-340-95939-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "About the Sentencing Council". sentencingcouncil.judiciary.gov.uk. 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ "CHAPTER ELEVEN ADMINISTRATIVE AND PUBLIC LAW" (PDF). nadr.co.uk/. Retrieved 7 August 2011.