La Salute è in voi! was an early 1900s bomb-making handbook associated with the Galleanisti, followers of anarchist Luigi Galleani, particularly in the United States. Translated as "Health Is in You!" or "Salvation Is within You!", its anonymous authors advocated for impoverished workers to overcome their despair and commit to individual, revolutionary acts. The Italian-language handbook offered plain directions to give non-technical amateurs the means to build explosives. Though this technical content was already available in encyclopedias, applied chemistry books, and industrial sources, La Salute è in voi wrapped this content within a political manifesto. Its contents included a glossary, basic chemistry training, and safety procedures. Its authors were likely Galleani and his friend Ettore Molinari, a chemist and anarchist.

The handbook was first advertised in Galleani's Cronaca Sovversiva, an anarchist newspaper, read by his American followers, in 1906. American police and historians would use the handbook to profile anarchists and imply guilt by possession. A decade after its release, La Salute è in voi! figured prominently in the prosecution of the 1915 Bresci Circle failed bombing of New York City's St. Patrick's Cathedral, in which the case revolved around the anarchists' right to read. Ultimately, the idea of amateurs learning to make bombs from simple instructions was impractical, as the perpetrators of successful political bombings from this era had career backgrounds in explosives.

Contents

This how-to handbook and anarchist manifesto encouraged workers to forgo their anguish, which only furthered their impoverishment, and instead commit to revolutionary acts.[1] It called for vengeance against oppressors and for finding "redemption" through "audacious revolt".[2] La Salute è in voi acknowledged that workers could not foment that revolution without the technical means and so provided readers plain directions for producing explosives.[1] Chapters include "Explosive Material", "Nitroglycerin", "Capsule and Petard", "Dynamite", "Fulminate of Mercury", and "Preparation of Fuses".[3]

It opens with an appeal to collective gain from individual action, using the example of an Italian town where rice laborers went on strike for wages in 1890. During their march to city hall, one hit a guard with a rock and the police fired on the crowd, killing three workers and wounding more, but ultimately the laborers gained their raise by dint of those martyred.[4] As an instruction manual, the book contains tips such as pre-testing explosives in the countryside, buying pure chemicals from pharmacists or dealers, purchasing from multiple vendors to avoid suspicion, and excuses to use if a vendor becomes suspicious.[5]

The handbook presents information in practical terms for laypeople, similar to a household textbook reference or farmer's almanac. It includes chemistry training, such as a Baumé scale to measure liquid density and determine the potency of compounds, but also provides potential household uses for the chemicals mentioned. It also includes safety procedures (e.g., if a reader drank nitric acid) and a glossary of terms and definitions. Its level of technical detail distinguished the handbook from other anarchist manifestos.[6]

Publication

Similar to John Most's Revolutionäre Kriegswissenschaft, La Salute è in voi was written to make military technology accessible to lay readers without chemistry and engineering expertise, such as the textile workers and anarchist writers of the eastern United States, who were inspired by other bombings but otherwise lacked occupational access to dynamite and practical experience in bomb-making.[7] Composed in elementary Italian, La Salute è in voi uses Italian terms and costs in lira.[8] Although its level of scientific detail regarding chemical-handling technique elevated the handbook from mere anarchist manifesto,[9] none of its contents were new. Its simple information was available in regular encyclopedias, applied chemistry books, and industrial sources, such as Martin Eissler's 1897 standard manual on explosives. La Salute è in voi did not contain complex formulas or time-detonator instructions.[4]

La Salute è in voi was written anonymously.[10] Its authors called themselves "the compilers"[4] and displayed a working familiarity with basic chemistry. This emphasis on science is likely owed to Ettore Molinari, a chemist and anarchist believed to have drafted an early version of the handbook, if not the full book.[8][9] Historians have been unable to find Molinari's Guerra all’oppressore (Italian for 'War Against Oppressors'), an earlier bomb-making manual that circulated among European anarchists.[11] In Paris, Molinari had befriended the Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani,[9] whose Italian-language, American anarchist newspaper, Cronaca Sovversiva (Italian for 'Subversion Chronicle'), would publish La Salute è in voi in the United States and introduce these technical instructions to his followers, the Galleanisti.[10] Galleani likely wrote the introductory reader note and poem himself.[8]

Cronaca Sovversiva first advertised La Salute è in voi for purchase in 1906 among other publications printed by the newspaper on its back page.[10][8] It was the newspaper's most expensive pamphlet: 25¢ (equivalent to $8 in 2022). La Salute è in voi featured more prominently in later editions of the newspaper as "an indispensable pamphlet for those comrades who love self-instruction".[8]

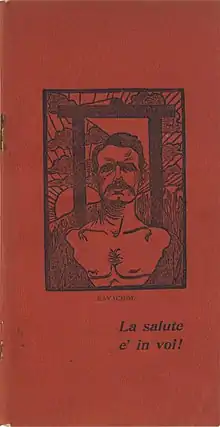

The 48-page handbook is tall and oblong,[8] bound in red covers. Its title, which translates to "Health Is in You!" or "Salvation Is within You!", may be an ironic reference to Christian anarchist Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You, which shares its Italian title with the bomb-making handbook. Unlike the Galleanisti, Tolstoy favored passive resistance and considered violence incompatible with Christian morality.[10] The handbook's cover illustration is a 1893 woodcut by French artist Charles Maurin depicting the French anarchist Ravachol in front of a guillotine, growing crops, and a symbolic new dawn.[12]

The printing contains a typographical error in which an "i", displayed as "1", would severely undercut the proportion of sulfuric acid in the nitroglycerin formula. Cronaca Sovversiva later ran a correction. Though some historians surmised that this error led to errant explosions, realistically the incorrect formula would have produced a mess of acids rather than the much more volatile nitroglycerin.[9]

Application

"Mere possession of this wicked treatise would suggest that the owner was up to no good."

New York bomb squad chief Thomas Tunney[3]

The police used the handbook to profile anarchist attackers, and historians have used the handbook as evidence of Galleanist responsibility for crimes.[10] La Salute è in voi had a low profile for the nine years prior to the 1915 Bresci Circle's attempted bombing of New York City's St. Patrick's Cathedral.[13] Though the handbook was never mentioned by name, it figured prominently in the prosecution of the Bresci Circle members; the prosecution used it to vilify the defendants despite no proof of its connection to the crime.[14] During and prior to arraignment one of the anarchists credited the handbook with deranging him, but the defendants' failed bomb components did not match those outlined in the handbook.[14] The police insinuated that possession of the handbook constituted evidence of the defendants' technical expertise and bad intentions. La Salute è in voi was the most sensational of the prosecution's seditious books used to show the anarchists' intents.[15] The anarchists' legal defense revolved around their right to read any books of any kind,[15] including bomb-making handbooks. They were ultimately found guilty.[16] The case rekindled fear of easily accessible bomb-making instructions and sensationalism around anarchism.[16]

The handbook's authors believed that amateurs would be able to build explosives by following simple directions but, in actuality, the era's successful perpetrators of political bombings had backgrounds in explosives from their respective industries. Workers in industries such as agriculture, construction, and mining had their own means for learning to make bombs or steal dynamite. Ann Larabee has written that the idea that untrained laborers could create bombs at home was and remains impractical, no more than an intellectual exercise.[7] The book did contain elements for neophytes, such as safety procedure and household uses for chemicals, which could double as cover stories and enhanced the handbook's subversiveness.[6] There is no evidence that Galleanists relied on La Salute è in voi but, if they did, the fact that their bombs hit only themselves and bystanders, never their intended capitalist and government targets, would indicate that the handbook provided insufficient preparation for an attack.[17]

After Sacco and Vanzetti, the Italian–American anarchists and international cause cèlébre, were denied appeal and condemned to death, they signed their final, written communique to supporters with "La Salute è in voi". Its invocation represented power through threat of violence. Though there is no direct evidence that they possessed or used a copy, especially as a bomb was not involved in their case, detectives and historians have thought of the handbook's existence among Galleanists as evidence of a broader conspiracy. For example, J. Edgar Hoover's investigation of the separate Wall Street bombing involved a dogged pursuit of a copy of the handbook.[18] Robert D'Attilio, a scholar of the Sacco and Vanzetti case, described the pamphlet as "the great unmentioned fact" of the trial, spoken of by neither the prosecution nor the defense,[8] yet nonetheless felt in the courtroom, which had been outfitted in advance of the trial with steel doors and bomb shutters to seal off the wing in the event of an bombing attack.[19] D'Attilio argued that both parties in the case had reasons for not mentioning the pamphlet: the prosecution, to avoid the appearance of collusion with federal investigations into the Galleanists, and the defense, to avoid alienating the jury amid the societal repression of alien radicals.[20]

After Sacco and Vanzetti, La Salute è in voi disappeared from public view, owing partially to its limited accessibility, based on its Italian language requirement, and limited topical interest.[18] A 1979 presentation at the Boston Public Library's Sacco and Vanzetti conference renewed interest in the booklet.[21]

References

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Avrich 1996, p. 98.

- 1 2 Gage 2009, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Larabee 2015, p. 39.

- ↑ Tejada 2012, p. 102.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 D'Attilio 1982, p. 81.

- 1 2 3 4 Larabee 2015, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Larabee 2015, p. 37.

- ↑ Mangini 2004.

- ↑ Avrich 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Larabee 2015, p. 41.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, p. 43.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, p. 44.

- ↑ Larabee 2015, p. 45.

- 1 2 Larabee 2015, p. 46.

- ↑ D'Attilio 1982, p. 87.

- ↑ D'Attilio 1982, p. 88.

- ↑ Larabee 2015, pp. 197–198.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Paul (1996). Sacco and Vanzetti: The Anarchist Background. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02604-6.

- D'Attilio, Robert (1982). "La Salute è in Voi: The Anarchist Dimension". Sacco-Vanzetti: Developments and Reconsiderations—1979. Boston Public Library. ISBN 978-0-89073-067-6.

- Gage, Beverly (2009). The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in Its First Age of Terror. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514824-4.

- Larabee, Ann (2015). "Sabotage". The Wrong Hands: Popular Weapons Manuals and Their Historic Challenges to a Democratic Society. Oxford University Press. pp. 36–63. ISBN 978-0-19-020117-3.

- Mangini, Giorgio (2004). "MOLINARI, Ettore". Dizionario biografico online degli anarchici italiani (in Italian). Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- Tejada, Susan (2012). In Search of Sacco and Vanzetti: Double Lives, Troubled Times, and the Massachusetts Murder Case That Shook the World. Northeastern. ISBN 978-1-55553-730-2.