Kingdom of Ormus هرمز | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century–1622 | |||||||

Flag | |||||||

| |||||||

| Status |

| ||||||

| Capital | 27°06′N 56°27′E / 27.100°N 56.450°E | ||||||

| Common languages | Persian,Arabic | ||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||

| Government | Kingdom | ||||||

| King | |||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 11th century | ||||||

| 1622 | |||||||

| |||||||

.jpg.webp)

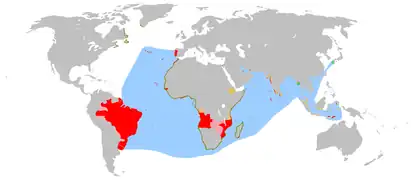

The Kingdom of Ormus (also known as Hormoz or Hormuz; Persian: هرمز; Portuguese: Ormuz) was located in the eastern side of the Persian Gulf and extended as far as Bahrain in the west at its zenith. The Kingdom was established in 11th century initially as a dependency of the Kerman Seljuk Sultanate, and later as an autonomous tributary of the Salghurids and the Ilkhanate of Iran.[1] In its last phase Ormus became a client state of the Portuguese Empire in the East. Most of its territory was eventually annexed by the Safavid Empire in the 17th century.

The monarchy received its name from the fortified port city which served as its capital. It was one of the most important ports in the Middle East at the time as it controlled seaway trading routes through the Persian Gulf to China, India, and East Africa. This port was originally located on the southern coast of Iran to the east of the Strait of Hormuz, near the modern city of Minab, and was later relocated to the island of Jarun which came to be known as Hormuz Island,[2] which is located near the modern city of Bandar-e Abbas.

Etymology

Popular etymology derives "Hormuz", being the Middle Persian pronunciation of the Persian deity Ahuramazda. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the name derives from Hur-Muz 'Place of Dates'.[3] Yet another possibility is that it comes from ὅρμος hormos, the Greek word for 'cove, bay'.[4] The name of the actual urban settlement that acted as the capital of the Old Hormoz Kingdom was also given as Naband.[5]

Old Hormuz

The original city of Hormoz was situated on the mainland in the province of Mogostan (Mughistan) near modern-day Minab in Hormozgan. At the time of the Ilkhanid competition with the Chaghataids, the old city of Hormoz, also known as Nabands and Dewankhana, was abandoned by its inhabitants. Instead, in 1301, the inhabitants, led by the king Baha ud-Din Ayaz and his wife Bibi Maryam, moved to the neighbouring island of Jerun.[6][7]

New Hormuz

"It was during the reign of Mir Bahrudin Ayaz Seyfin, fifteenth king of Hormoz, that the Seljuks raided the kingdom of Kerman and from there to that of Hormoz. The wealth of Hormoz attracted raids so often that the inhabitants sought refuge off the mainland and initially moved to the island of Qeshm. Mir Bahrudin then visited the island of Jerun and obtained it from Neyn (Na'im), King of Keys (Kish), to whom all the islands in the area belonged. After undertaking the Hajj pilgrimage, Mir Bahrudin became widely known as Haji Bahrudin in the lands of Hormuz."[8]

Risso writes: "In the eleventh century, Saljûq Persia developed at the expense of what was left of Buwayhid Mesopotamia and the Saljûqs controlled ‘Umânî ports from about 1065 to 1140. Fatimid Egypt attracted trade to the Red Sea route and away from the Persian Gulf. These shifts in power marked the end of the [Persian] Gulf's heyday, but the island ports of Qays and then the mainland port of Hormoz (at first tributary to Persia) became renowned entrepôts. The Hurmuzî rulers developed Qalhât on the ‘Umânî coast in order to control both sides of the entrance to the Persian Gulf. Later, in 1300, the Hurmuzî merchants cast off Persian overlordship. and reorganized their entrepôt on the island also called Hurmuz and there amassed legendary wealth. The relationship. between the Nabâhina and the Hurmuzîs is obscure".[9]

Abbé T G F Raynal gives the following account of Hormoz in his history: Hormoz became the capital of an empire which comprehended a considerable part of Arabia on one side, and Persia on the other. At the time of the arrival of the foreign merchants, it afforded a more splendid and agreeable scene than any city in the East. Persons from all parts of the globe exchanged their commodities and transacted their business with an air of politeness and attention, which are seldom seen in other places of trade. The streets were covered with mats and in some places with carpet, and the linen awnings which were suspended from the tops of the houses, prevented any inconvenience from the heat of the sun. India cabinets ornamented with gilded vases, or china filled with flowering shrubs or aromatic plants adorned their apartments. Camels laden with water were stationed in the public squares. Persian wines, perfumes, and all the delicacies of the table were furnished in great abundance, and they had the music of the East in its highest perfection ... In short, universal opulence, an extensive commerce, politeness in the men and gallantry in the women, united all their attractions to make this city the seat of pleasure.[10]

Hormuz enjoyed a long period of autonomy under the suzerainty of kings of Iran from the foundation of the kingdom in the 11th century to the coming of the Portuguese.[4] It was ruled by the children of Muhammad Deramku (Deramkub "Dirham minter") who founded the kingdom as a dependency of the Kingdom of Kerman after the collapse of the Buyid kingdom, reaching its apogee under the rule of the Mongol dynasty of the Ilkhanids.[11] In the medieval period, the kingdom was well known as an international emporium controlling both sides of the Persian Gulf and much of the coastal area of the Arabian Sea and well known in Europe as a commercial hub.[4] Its success in fact led to its fame, prompting the Portuguese to launch attacks on it and conquer it in the early 16th century.[11]

In the early 15th century, Hormuz was one the kingdoms that was visited by the Chinese expeditionary fleet commanded by Admiral Zheng He during the Ming treasure voyages and was the final destination of the fleet during the fourth voyage.[12][13] Ma Huan, an interpreter serving in the crew, described Hormuz society in a positive light in the Yingya Shenglan, writing for example about the people that "the limbs and faces of the people are refined and fair [...] and they are stalwart and fine-looking; their clothing and hats are handsome, distinctive and elegant."[13] Fei Xin, another crew member, made an account of Hormuz in the Xingcha Shenglan.[13] It included, for instance, observations suggesting that Hormuz society had a high standard of living, writing that "the lower classes are wealthy", and on local dressing habits such as the long robes worn by both men and women, the veils that women wore over their head and face when going out, and the jewels worn by the well-to-do.[13]

.jpg.webp)

Portuguese conquest

In September 1507, the Portuguese Afonso de Albuquerque landed on the island. Portugal occupied Ormuz from 1515 to 1622.

As vassals of the Portuguese state, the Kingdom of Ormus jointly participated in the 1521 invasion of Bahrain that ended Jabrid rule of the Persian Gulf archipelago. The Jabrid ruler was nominally a vassal of Ormus, but the Jabrid King, Muqrin ibn Zamil had refused to pay the tribute Ormus demanded, prompting the invasion under the command of the Portuguese conqueror, António Correia.[14] In the fighting for Bahrain, most of the combat was carried out by Portuguese troops, while the Ormusi admiral, Reis Xarafo, looked on.[15] The Portuguese ruled Bahrain through a series of Ormusi governors. However, the Sunni Ormusi were not popular with Bahrain's Shia population which suffered religious disadvantages,[16] prompting rebellion. In one case, the Ormusi governor was crucified by rebels,[17] and Portuguese rule came to an end in 1602 after the Ormusi governor, who was a relative of the Ormusi king,[18] started executing members of Bahrain's leading families.[19]

The kings of Hormuz under Portuguese rule were reduced to vassals of the Portuguese empire in India, mostly controlled from Goa. The archive of correspondence between the kings and local rulers of Hormuz,[20] and some of its governors and people, and the kings of Portugal, contain the details of the kingdom's disintegration and the independence of its various parts. They show the attempts by rulers such as Kamal ud-Din Rashed trying to gain separate favour with the Portuguese in order to guarantee their own power.[21] This reflects in the gradual independence of Muscat, previously a dependency of Hormuz, and its rise one of the successor states to Hormuz.

After the Portuguese made several abortive attempts to seize control of Basra, the Safavid ruler Abbas I of Persia conquered the kingdom with the help of the English, and expelled the Portuguese from the rest of the Persian Gulf, with the exception of Muscat. The Portuguese returned to the Persian Gulf in the following year as allies of Afrasiyab, the Pasha of Basra, against the Persians. Afrasiyab was formerly an Ottoman vassal but had been effectively independent since 1612. They never returned to Ormus.

In the mid-17th century it was captured by the Imam of Muscat, but was subsequently recaptured by Persians. Today, it is part of the Iranian province of Hormozgan.

Accounts of Ormus society

Situated between the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, Ormus was a "by-word for wealth and luxury",[22] perhaps best captured in the Arab saying: "If all the world were a golden ring, Ormus would be the jewel in it".[22] The city was also known for its licentiousness according to accounts by Portuguese visitors; Duarte Barbosa, one of the first Portuguese to travel to Ormuz in the early 16th century found:

The merchants of this isle and city are Persians and Arabs. The Persians [speak Arabic and another language which they call Psa[23]], are tall and well-looking, and a fine and up-standing folk, both men and women; they are stout and comfortable. They hold the creed of Muhammad in great honour. They indulge themselves greatly, so much so that they keep among them youths for the purpose of abominable wickedness. They are musicians, and have instruments of diverse kinds. [24]

This theme is also strong in Henry James Coleridge's account of Ormus in his life of the Navarrese missionary, St Francis Xavier, who visited Ormus on his way to Japan:

Its moral state was enormously and infamously bad. It was the home of the foulest sensuality, and of all the most corrupted forms of every religion in the East. The Christians were as bad as the rest in the extreme license of their lives. There were few priests, but they were a disgrace to their name. The Arabs and the Persians had introduced and made common the most detestable forms of vice. Ormuz was said to be a Babel for its confusion of tongues, and for its moral abominations to match the cities of the Plain. A lawful marriage was a rare exception. Foreigners, soldiers and merchants, threw off all restraint in the indulgence of their passions ... Avarice was made a science: it was studied and practiced, not for gain, but for its own sake, and for the pleasure of cheating. Evil had become good, and it was thought good trade to break promises and think nothing of engagements ...[25]

Depiction in literature

Ormus is mentioned in a passage from John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (Book II, lines 1–5) where Satan's throne "Outshone the wealth of Ormus and of Ind", which Douglas Brooks states is Milton linking Ormus to the "sublime but perverse orient".[26] It is also mentioned in Andrew Marvell's poem 'Bermudas', where pomegranates are described as "jewels more rich than Ormus shows." In Hart Crane's sonnet To Emily Dickinson, it appears in the couplet: "Some reconcilement of remotest mind– / Leaves Ormus rubyless, and Ophir chill." The closet drama Alaham by Fulke Greville is set in Ormus. The kingdom of Ormus, referred to as 'Ormuz', is described in Hilary Mantel's novel Wolf Hall as "the driest kingdom in the world, where there are no trees and no crop but salt. Stand at its centre, and you look over thirty miles in all directions of ashy plain: beyond which lies the seashore, encrusted with pearls."

See also

References

- ↑ Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p.122

- ↑ Shabankareyi, Muhammad. Majma al-Ansab. p. 215.

- ↑ Ebrahimi, Qorbanali (1384). "Hormoz-Hormuz". Motale'at Irani. 4 (7): 48.

- 1 2 3 Rezakhani, Khodadad (27 February 2020). "The Kingdom of Hormuz". Iranologie.com. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ↑ Shabankareyi, Muhammad b. Ali (1363). Majma al-Ansab. Tehran: Amir Kabir. p. 215.

- ↑ Vosoughi, M. B. The Kings of Hormoz. p. 92.

- ↑

- 127 The Travels of Marco Polo the Venetian, J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd; E.P. Dutton & Co, London and Toronto; New York, 1926 ~ p. 63. Although Marco Polo refers to the island on which was the city of Hormoz, Collis states that at that time Hormoz was on the mainland. #85 Collis, Maurice. Marco Polo. London, Faber and Faber Limited, 1959~ p. 24.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Risso, Patricia, Oman And Muscat: an Early Modern History, Croom Helm, London, 1986 ~ p. 10.

- ↑

- 252 Stiffe, A. W., "The Island of Hormoz (Ormuz)", Geographical Magazine, London, 1874 (Apr.), vol. 1 pp. 12–17 ~ p. 14

- 1 2 Floor, Willem. "Hormuz ii. Islamic Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ↑ Dreyer, Edward L. (2007). Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405–1433. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0321084439.

- 1 2 3 4 Kauz, Ralph; Ptak, Roderich (2001). "Hormuz in Yuan and Ming sources". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 88: 27–75. doi:10.3406/befeo.2001.3509. JSTOR 43731513.

- ↑ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham Travels in Assyria, Media, and Persia, Oxford University Press, 1829, p459

- ↑ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 pp39

- ↑ Charles Belgrave, Personal Column, Hutchinson, 1960 p98

- ↑ Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p6

- ↑ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984 p69

- ↑ Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-e Porteghal". Asnad.

- ↑ Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki..." Asnad.

- 1 2 Peter Padfield, Tide of Empires: Decisive Naval Campaigns in the Rise of the West, Routledge 1979 p65

- ↑ pesh, a Semitic root for 'mouth', often connotes speech.

- ↑ The Book of Duarte Barbosa: An Account of the Countries Bordering on the Indian Ocean and their inhabitants, written by Duarte Barbosa and completed about the year 1518 AD, 1812 translation by the Royal Academy of Sciences Lisbon, Asian Educational Services 2005

- ↑ Francis Xavier, Henry James Coleridge, The Life and Letters of St. Francis Xavier 1506–1556, Asian Educational Services 1997 Edition p 104–105

- ↑ Brooks, Douglas (31 March 2008). Milton and the Jews. Cambridge University Press. pp. 188–. ISBN 9781139471183. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

Bibliography

- Aubin, Jean. “Les Princes d’Ormuz du XIIIe au XVe siècle.” Journal asiatique, vol. CCXLI, 1953, pp. 77–137.

- Natanzi, Mo'in ad-Din. Montakhab ut-Tawarikh-e Mo'ini. ed. Parvin Estakhri. Tehran: Asateer, 1383 (2004).

- Qa'em Maqami, Jahangir. "Asnad-e Farsi o Arabi o Torki dar Arshiv-e Melli-ye Porteghal Darbarey-e Hormuz o Khaleej-e Fars." Barrasihaa-ye Tarikhi (1356–1357).

- Shabankareyi, Muhammad b Ali. Majma al-Ansab. ed. Mir-Hashem Mohadess. Tehran: Amir Kabir, 1363 (1984).

- Vosoughi, Mohammad Bagher. "the Kings of Hormuz: from the Beginning until the Arrival of the Portuguese." in Lawrence G. Potter (ed.) The Persian Gulf in History, New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009.