| Dagobert I | |

|---|---|

| King of the Franks | |

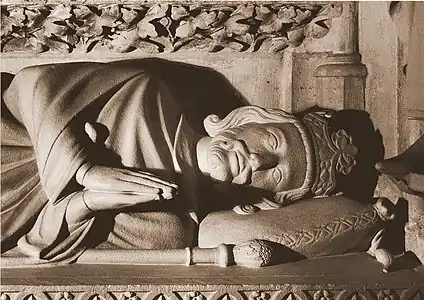

Contemporary effigy of Dagobert from a gold triens | |

| King in Austrasia | |

| Reign | 623–634 |

| Predecessor | Chlothar II |

| Successor | Sigebert III |

| King in Neustria and Burgundy | |

| Reign | October 629 – 19 January 639 |

| Predecessor | Chlothar II |

| Successor | Clovis II |

| Born | c. 605/603 |

| Died | 19 January 639 (aged 35-36) Épinay-sur-Seine |

| Burial | |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Merovingian |

| Father | Chlothar II |

| Mother | Haldetrude |

| Signature | |

Dagobert I (Latin: Dagobertus; c. 605/603 – 19 January 639 AD)[1] was King of the Franks. He ruled Austrasia (623–634) and Neustria and Burgundy (629–639). He has been described as the last king of the Merovingian dynasty to wield real royal power.[2] Dagobert was the first Frankish king to be buried in the royal tombs at the Basilica of Saint-Denis.[3]

Rule in Austrasia

Dagobert was the eldest son of Chlothar II and Haldetrude (575–604) and the grandson of Fredegund.[4] Chlothar had reigned alone over all the Franks since 613. In 622, Chlothar made Dagobert king of Austrasia,[5] almost certainly to bind the Austrasian nobility to the ruling Franks.[4][6] As a child, Dagobert lived under the care of the Carolingian dynasty forebears and Austrasian magnates, Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen.[7]

Chlothar attempted to manage the unstable alliances he had with other noble families throughout much of Dagobert's reign.[8] When Chlothar granted Austrasia to Dagobert, he initially excluded Alsace, the Vosges, and the Ardennes, but shortly thereafter the Austrasian nobility forced him to concede these regions to Dagobert. The rule of a Frank from the Austrasian heartland tied Alsace more closely to the Austrasian court. Dagobert created a new duchy (the later Duchy of Alsace) in southwest Austrasia to guard the region from Burgundian or Alemannic encroachments and ambitions. The duchy comprised the Vosges, the Burgundian Gate, and the Transjura. Dagobert made his courtier Gundoin—who incidentally established monasteries in Alsace and Burgundy[9]—the first duke of this new polity that was to last until the end of the Merovingian dynasty. While Austrasian rulers such as Chlothar and Dagobert controlled these regions through part of the seventh-century, they eventually became autonomous kingdoms as powerful aristocratic families sought separate paths across their respective realms.[10]

United rule

Upon the death of his father in 629, Dagobert inherited the Neustrian and Burgundian kingdoms. His half-brother Charibert, son of Sichilde, claimed Neustria but Dagobert opposed him. Brodulf, brother of Sichilde, petitioned Dagobert on behalf of his young nephew, but Dagobert assassinated him and became sole king of the Franks. He later gave the Aquitaine to Charibert as a "consolation prize."[11] In 629, Dagobert concluded a treaty with the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, which entailed enforcing the compulsory baptism of Jews throughout his kingdom.[12] Besides signing this treaty, Dagobert also took steps to secure trade across his empire by protecting important markets along the mouth of the Rhine at Duurstede and Utrecht, which in part explains his later determination to defend the Austrasian Franks from the Avar menace.[13]

Under the rule of Dagobert's father and like-minded Merovingians, Frankish society during the seventh-century experienced greater integration—the Catholic faith became predominant for instance—and a generally improved economic situation, but there was no initial impetus for the political unification of Gaul. Clothar II did not seek to force his Neustrian neighbors into submission, choosing instead a policy of cooperation.[14] This did not prohibit plunder-raids to replenish the dynastic coffers, which Dagobert undertook in Spain for example—one raid there earned him 200,000 gold solidi.[15] Historian Ian Wood claims that Dagobert "was probably richer than most Merovingian monarchs" and cites for example his assistance to the Visigoth Sisenand—whom he aided in his rise to the Visigothic throne in Spain—and for which, Sisenand awarded Dagobert a golden dish weighing some 500 pounds (230 kg).[16]

When Charibert and his son Chilperic were assassinated in 632, Dagobert had Burgundy and Aquitaine firmly under his rule, becoming the most powerful Merovingian king in many years and the most respected ruler in the West. In 631, Dagobert led a large army against Samo, the ruler of the Slavic Wends, partly at the request of the Germanic peoples living in the eastern territories and also due to Dagobert's quarrel with him about the Wends having robbed and killed a number of Frankish merchants.[17] While Dagobert's Austrasian forces were defeated at the Wogastisburg,[18] his Alemannic and Lombard allies were successful in repelling the Wends.[19] Taking advantage of the situation at the time, the Saxons offered to help Dagobert if he agreed to rescind the 500 cow yearly tribute to the Austrasians. Despite accepting this agreement, Fredegar reports that it was to little avail since the Wends attacked again the following year.[19]

Rule in Neustria, from Paris

Also in 632, the nobles of Austrasia revolted under the mayor of the palace, Pepin of Landen. In 634, Dagobert appeased the rebellious nobles by putting his three-year-old son, Sigebert III, on the throne, thereby ceding royal power in the easternmost of his realms, just as his father had done for him eleven years earlier. In historian Ian Wood's view, Dagobert's creation of a sub-kingdom for his son Sigibert had "important long-term implications for the general structure of Merovingian Francia."[20]

As king, Dagobert made Paris his capital. During his reign, he built the Altes Schloss in Meersburg (in modern Germany), which today is the oldest inhabited castle in that country. Devoutly religious, Dagobert was also responsible for the construction of the Saint Denis Basilica at the site of a Benedictine monastery in Paris. He also appointed St. Arbogast bishop of Strasbourg.[21] Dagobert was beloved in many ways according to Fredegar, who wrote that "He rendered justice to rich and poor alike," adding that, "he took little sleep or food, and cared only so to act that all men should leave his presence full of joy and admiration."[22] Such images do not fully convey the power and domination wielded by Frankish kings like Dagobert, who along with his father Chlothar, reigned to such a degree that historian Patrick Geary described the period of their combined rule as the "apogee of Merovingian royal power."[23]

Dagobert went down in history as one of the greatest Frankish kings, in spite of his mediocre military record (cf. his defeats by the Saxons and the Wends), having held his lands against the eastern hordes and with noblemen as far away as Bavaria, who sought his overlordship.[24] Only thirty six when he died, Dagobert is considered the last of the great Merovingian kings by most historians, but this does not mean there was a major waning in Frankish power, especially in light of the writings of Paul the Deacon and John of Toledo.[25] J.M. Wallace-Hadrill stated that Dagobert "had the ruthless energy of a Clovis and the cunning of a Charlemagne."[24] Despite having more or less united the Frankish realms, he likely was not expecting unitary rule to continue given the diverging interests of the Austrasian and Neustrian Franks, atop those of the Aquitanians and Burgundians.[24] Upon Dagobert's death in 639, Pepin of Landen was able to recoup his position at Metz.[26] Meanwhile, Dagobert was buried in the abbey of Saint Denis Basilica, Paris, the first Frankish king to be buried there.[27] Dagobert's interment at Saint-Denis established a precedent for the burial of future French rulers there.[28]

Legacy

The pattern of division and assassination, which characterized king Dagobert's reign, continued for the next century until Pepin the Short finally deposed the last Merovingian king in 751, establishing the Carolingian dynasty. The Merovingian boy-kings remained ineffective rulers who inherited the throne as young children and lived only long enough to produce a male heir or two, while real power lay in the hands of the noble families who exercised feudal control over most of the land.

In the 830s, a biography of Dagobert, the Gesta Dagoberti, was written, probably by Hincmar. It is mostly unreliable, but does contains some information based on authentic archival documents.[29] Dagobert was immortalized in the song Le bon roi Dagobert (The Good King Dagobert), a nursery rhyme featuring exchanges between the king and his chief adviser, Saint Eligius (Eloi in French). The satirical rhymes place Dagobert in various ridiculous positions from which Eligius' good advice manages to extract him. The text, which probably originated in the 18th century, became extremely popular as an expression of the anti-monarchist sentiment of the French Revolution. Other than placing Dagobert and Eligius in their respective roles, it has no historical accuracy.

In 1984, a 112 minute long French-Italian comedy, Le bon roi Dagobert (Good King Dagobert) was made, based on Dagobert I. The soundtrack was composed by Guido & Maurizio De Angelis, Starring Ugo Tognazzi, Coluche and Michel Serrault.

Marriage and children

According to the Chronicle of Fredegar Dagobert I had "three queens almost simultaneously, as well as several concubines".[lower-alpha 1][30] The rex Brittanorum Judicael came to Clichy to visit Dagobert I, but opted not to dine with him due to his misgivings about Dagobert's moral choices, instead dining with the king's referendary St. Audoen.[31]

The Chronicle of Fredegar names three queens. Nanthild, Wulfegundis, and Berchildis, but none of the concubines. In 625/6 Dagobert married Gormatrude, a sister of his father's wife Sichilde. The marriage was childless. After divorcing Gormatrude in 629/30 he made Nanthild, a Saxon servant (puella) from his personal entourage, his new queen.[lower-alpha 2] She gave birth to Clovis II (b. 634/5) later king of Neustria and Burgundy.

Shortly after his marriage to Nanthild, a woman called Ragnetrude bore Dagobert I a son, Sigebert III (b. 630/1) later king of Austrasia. It has been speculated that Regintrud, abbess of Nonnberg Abbey, was also a child of Dagobert I, although this theory does not fit Regintrud's supposed date of birth between 660 and 665. She married into the Bavarian Agilolfing family, either Theodo of Bavaria or his son Theodbert of Bavaria.

Coinage and treasures under Dagobert

Treasures of Dagobert

Treasures of Dagobert - Abel Hugo - France historique et monumentale (1837).

Treasures of Dagobert - Abel Hugo - France historique et monumentale (1837).

Throne of Dagobert (detail)

Throne of Dagobert (detail)

Coinage

Triens of Dagobert I and moneyer Romanos, Augaune, 629-639, gold 1.32g. Monnaie de Paris.

Triens of Dagobert I and moneyer Romanos, Augaune, 629-639, gold 1.32g. Monnaie de Paris.

References

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Oldfield 2014, p. 218.

- ↑ Williams 2005, p. 52.

- ↑ Duby 1991, p. 134.

- 1 2 Frassetto 2003, p. 139.

- ↑ Geary 1988, p. 154.

- ↑ Riché 1993, p. 16.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 77.

- ↑ Frassetto 2003, p. 121.

- ↑ Geary 1988, p. 177.

- ↑ Geary 1988, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Deutsch 2013, p. 96.

- ↑ Meriaux 2019, p. 144.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 79.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill 2004, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ Wood 1994, p. 65.

- ↑ James 1988, p. 105.

- ↑ Jaques 2011, p. 1109.

- 1 2 James 1988, p. 106.

- ↑ Wood 1994, p. 145.

- ↑ Farmer 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Durant 1950, p. 460.

- ↑ Geary 2002, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Wallace-Hadrill 2004, p. 80.

- ↑ Fouracre 2005, p. 380.

- ↑ Riché 1993, p. 18.

- ↑ Frassetto 2003, p. 140.

- ↑ Horne 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Wood 1994, pp. 148, 155, 169.

- ↑ Durant 1950, p. 94, 460.

- ↑ James 1988, p. 101.

Bibliography

- Deutsch, Lorànt (2013). Metronome: A History of Paris from the Underground Up. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-25002-367-4.

- Duby, Georges (1991). France in the Middle Ages 987–1460: From Hugh Capet to Joan of Arc. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-18945-9.

- Durant, Will (1950). The Age of Faith. The Story of Civilization. Vol. IV. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 225699907.

- Farmer, Hugh (2011). Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19959-660-7.

- Fouracre, Paul (2005). "Francia in the Seventh Century". In Paul Fouracre (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. I [c.500–c.700]. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52136-291-7.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-263-9.

- Geary, Patrick J. (1988). Before France and Germany: The Creation & Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19504-458-4.

- Geary, Patrick J. (2002). The Myth of Nations: The Medieval Origins of Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-69109-054-2.

- Horne, Alistair (2004). La Belle France: A Short History. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-40003-487-1.

- Jaques, Tony (2011). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P–Z. Vol. 3. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-31333-539-6.

- James, Edward (1988). The Franks. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-14872-8.

- Meriaux, Charles (2019). "A One-Way Ticket to Francia: Constantinople, Rome, and Northern Gaul in the Mid-Seventh Century". In Stefan Esders; Yaniv Fox; Yitzhak Hen; Laury Sarti (eds.). East and West in the Early Middle Ages: The Merovingian Kingdoms in Mediterranean Perspective. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10718-715-3.

- Oldfield, Paul (2014). Sanctity and Pilgrimage in Medieval Southern Italy, 1000–1200. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-51171-993-6.

- Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Translated by Michael Idomir Allen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81221-342-3.

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (2004). The Barbarian West, 400–1000. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63120-292-9.

- Williams, Rose (2005). The Lighter Side of The Dark Ages. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-192-5.

- Wood, Ian (1994). The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751. London and New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49372-2.