| Æthelwulf | |

|---|---|

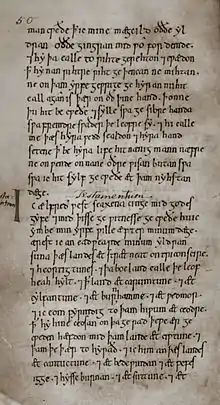

Æthelwulf in the early fourteenth-century Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England | |

| King of Wessex | |

| Reign | 839–858 |

| Predecessor | Ecgberht |

| Successor | Æthelbald |

| Died | 13 January 858 |

| Burial | Steyning then Winchester |

| Spouse | |

| Issue | |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Ecgberht, King of Wessex |

Æthelwulf (Old English: [ˈæðelwuɫf];[1] Old English for "Noble Wolf";[2] died 13 January 858) was King of Wessex from 839 to 858.[lower-alpha 1] In 825, his father, King Ecgberht, defeated King Beornwulf of Mercia, ending a long Mercian dominance over Anglo-Saxon England south of the Humber. Ecgberht sent Æthelwulf with an army to Kent, where he expelled the Mercian sub-king and was himself appointed sub-king. After 830, Ecgberht maintained good relations with Mercia, and this was continued by Æthelwulf when he became king in 839, the first son to succeed his father as West Saxon king since 641.

The Vikings were not a major threat to Wessex during Æthelwulf's reign. In 843, he was defeated in a battle against the Vikings at Carhampton in Somerset, but he achieved a major victory at the Battle of Aclea in 851. In 853, he joined a successful Mercian expedition to Wales to restore the traditional Mercian hegemony, and in the same year his daughter Æthelswith married King Burgred of Mercia. In 855, Æthelwulf went on pilgrimage to Rome. In preparation he gave a "decimation", donating a tenth of his personal property to his subjects; he appointed his eldest surviving son Æthelbald to act as King of Wessex in his absence, and his next son Æthelberht to rule Kent and the south-east. Æthelwulf spent a year in Rome, and on his way back he married Judith, the daughter of the West Frankish king Charles the Bald.

When Æthelwulf returned to England, Æthelbald refused to surrender the West Saxon throne, and Æthelwulf agreed to divide the kingdom, taking the east and leaving the west in Æthelbald's hands. On Æthelwulf's death in 858, he left Wessex to Æthelbald and Kent to Æthelberht, but Æthelbald's death only two years later led to the reunification of the kingdom. In the 20th century Æthelwulf's reputation among historians was poor: he was seen as excessively pious and impractical, and his pilgrimage was viewed as a desertion of his duties. Historians in the 21st century see him very differently, as a king who consolidated and extended the power of his dynasty, commanded respect on the continent, and dealt more effectively than most of his contemporaries with Viking attacks. He is regarded as one of the most successful West Saxon kings, who laid the foundations for the success of his son, Alfred the Great.

Background

At the beginning of the 9th century, England was almost completely under the control of the Anglo-Saxons, with Mercia and Wessex the most important southern kingdoms. Mercia was dominant until the 820s, and it exercised overlordship over East Anglia and Kent, but Wessex was able to maintain its independence from its more powerful neighbour. Offa, king of Mercia from 757 to 796, was the dominant figure of the second half of the 8th century. King Beorhtric of Wessex (786–802), married Offa's daughter in 789. Beorhtric and Offa drove Æthelwulf's father Ecgberht into exile, and he spent several years at the court of Charlemagne in Francia. Ecgberht was the son of Ealhmund, who had briefly been King of Kent in 784. Following Offa's death, King Coenwulf of Mercia (796–821) maintained Mercian dominance, but it is uncertain whether Beorhtric ever accepted political subordination, and when he died in 802 Ecgberht became king, perhaps with the support of Charlemagne.[5] For two hundred years three kindreds had fought for the West Saxon throne, and no son had followed his father as king. Ecgberht's best claim was that he was the great-great-grandson of Ingild, brother of King Ine (688–726), and in 802 it would have seemed very unlikely that he would establish a lasting dynasty.[6]

Almost nothing is recorded of the first twenty years of Ecgberht's reign, apart from campaigns against the Cornish in the 810s.[7] The historian Richard Abels argues that the silence of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was probably intentional, concealing Ecgberht's purge of Beorhtric's magnates and suppression of rival royal lines.[8] Relations between Mercian kings and their Kentish subjects were distant. Kentish ealdormen did not attend the court of King Coenwulf, who quarrelled with Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury (805–832) over the control of Kentish monasteries; Coenwulf's primary concern seems to have been to gain access to the wealth of Kent. His successors Ceolwulf I (821–823) and Beornwulf (823–826) restored relations with Archbishop Wulfred, and Beornwulf appointed a sub-king of Kent, Baldred.[9]

England had suffered Viking raids in the late 8th century, but no attacks are recorded between 794 and 835, when the Isle of Sheppey in Kent was ravaged.[10] In 836, Ecgberht was defeated by the Vikings at Carhampton in Somerset,[7] but in 838, he was victorious over an alliance of Cornishmen and Vikings at the Battle of Hingston Down, reducing Cornwall to the status of a client kingdom.[11]

Family

Æthelwulf's father Ecgberht was king of Wessex from 802 to 839. His mother's name is unknown, and he had no recorded siblings. He is known to have had two wives in succession, and so far as is known, Osburh, the senior of the two, was the mother of all his children. She was the daughter of Oslac, described by Asser, biographer of their son Alfred the Great, as "King Æthelwulf's famous butler",[lower-alpha 2] a man who was descended from Jutes who had ruled the Isle of Wight.[13][14] Æthelwulf had six known children. His eldest son, Æthelstan, was old enough to be appointed King of Kent in 839, so he must have been born by the early 820s, and he died in the early 850s.[lower-alpha 3] The second son, Æthelbald, is first recorded as a charter witness in 841, and if, like Alfred, he began to attest when he was around six, he would have been born around 835; he was King of Wessex from 858 to 860. Æthelwulf's third son, Æthelberht, was probably born around 839 and was king from 860 to 865. The only daughter, Æthelswith, married Burgred, King of Mercia, in 853.[16] The other two sons were much younger: Æthelred was born around 848 and was king from 865 to 871, and Alfred was born around 849 and was king from 871 to 899.[17] In 856, Æthelwulf married Judith, daughter of Charles the Bald, King of West Francia and future Carolingian Emperor, and his wife Ermentrude. Osburh had probably died, although it is possible that she had been repudiated.[lower-alpha 4] There were no children from Æthelwulf's marriage to Judith, and after his death, she married his eldest surviving son and successor, Æthelbald.[13]

Early life

Æthelwulf was first recorded in 825, when Ecgberht won the crucial Battle of Ellandun in Wiltshire against King Beornwulf of Mercia, ending the long Mercian ascendancy over southern England. Ecgberht followed it up by sending Æthelwulf with Eahlstan, Bishop of Sherborne, and Wulfheard, Ealdorman of Hampshire, with a large army into Kent to expel sub-king Baldred.[lower-alpha 5] Æthelwulf was descended from kings of Kent, and he was sub-king of Kent, and of Surrey, Sussex and Essex, which were then included in the sub-kingdom, until he inherited the throne of Wessex in 839.[22] His sub-kingship is recorded in charters, in some of which King Ecgberht acted with his son's permission,[13] such as a grant in 838 to Bishop Beornmod of Rochester, and Æthelwulf himself issued a charter as King of Kent in the same year.[23] Unlike their Mercian predecessors, who alienated the Kentish people by ruling from a distance, Æthelwulf and his father successfully cultivated local support by governing through Kentish ealdormen and promoting their interests.[24] In Abels' view, Ecgberht and Æthelwulf rewarded their friends and purged Mercian supporters.[25][lower-alpha 6] Historians take differing views on the attitude of the new regime to the Kentish church. At Canterbury in 828, Ecgberht granted privileges to the bishopric of Rochester, and according to the historian Simon Keynes, Ecgberht and Æthelwulf took steps to secure the support of Archbishop Wulfred.[27] However, Nicholas Brooks argues that Wulfred's Mercian origin and connections proved a liability. Æthelwulf seized an estate in East Malling from the Canterbury church on the ground that it had only been granted by Baldred when he was in flight from the West Saxon forces; the issue of archiepiscopal coinage was suspended for several years; and the only estate Wulfred was granted after 825 he received from King Wiglaf of Mercia.[28]

In 829, Ecgberht conquered Mercia, only for Wiglaf to recover his kingdom a year later.[29] The scholar David Kirby sees Wiglaf's restoration in 830 as a dramatic reversal for Ecgberht, which was probably followed by his loss of control of the London mint and the Mercian recovery of Essex and Berkshire,[30] and the historian Heather Edwards states that his "immense conquest could not be maintained".[7] However, in the view of Keynes:

It is interesting ... that both Ecgberht and his son Æthelwulf appear to have respected the separate identity of Kent and its associated provinces, as if there appears to have been no plan at this stage to absorb the southeast into an enlarged kingdom stretching across the whole of southern England. Nor does it seem to have been the intention of Ecgberht and his successors to maintain supremacy of any kind over the kingdom of Mercia ... It is quite possible that Ecgberht had relinquished Mercia of his own volition; and there is no suggestion that any residual antagonism affected relations between the rulers of Wessex and Mercia thereafter.[31]

In 838, King Ecgberht held an assembly at Kingston in Surrey, where Æthelwulf may have been consecrated as king by the archbishop. Ecgberht restored the East Malling estate to Wulfred's successor as Archbishop of Canterbury, Ceolnoth, in return for a promise of "firm and unbroken friendship" for himself and Æthelwulf and their heirs, and the same condition is specified in a grant to the see of Winchester.[lower-alpha 7] Ecgberht thus ensured support for Æthelwulf, who became the first son to succeed his father as West Saxon king since 641.[33] At the same meeting, Kentish monasteries chose Æthelwulf as their lord, and he undertook that, after his death, they would have freedom to elect their heads. Wulfred had devoted his archiepiscopate to fighting against secular power over Kentish monasteries, but Ceolnoth now surrendered effective control to Æthelwulf, whose offer of freedom from control after his death was unlikely to be honoured by his successors. Kentish ecclesiastics and laymen now looked for protection against Viking attacks to West Saxon rather than Mercian royal power. [34]

Ecgberht's conquests brought him wealth far greater than his predecessors had enjoyed, and enabled him to purchase the support which secured the West Saxon throne for his descendants.[35] The stability brought by the dynastic succession of Ecgberht and Æthelwulf led to an expansion of commercial and agrarian resources, and to an expansion of royal income.[36] The wealth of the West Saxon kings was also increased by the agreement in 838–839 with Archbishop Ceolnoth for the previously independent West Saxon minsters to accept the king as their secular lord in return for his protection.[37] However, there was no certainty that the hegemony of Wessex would prove more permanent than that of Mercia.[38]

King of Wessex

When Æthelwulf succeeded to the throne of Wessex in 839, his experience as sub-king of Kent had given him valuable training in kingship, and he in turn made his own sons sub-kings.[39] According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, on his accession "he gave to his son Æthelstan the kingdom of the people of Kent, and the kingdom of the East Saxons [Essex] and of the people of Surrey and of the South Saxons [Sussex]". However, Æthelwulf did not give Æthelstan the same power as his father had given him, and although Æthelstan attested his father's charters[lower-alpha 8] as king, he does not appear to have been given the power to issue his own charters. Æthelwulf exercised authority in the south-east and made regular visits there. He governed Wessex and Kent as separate spheres, and assemblies in each kingdom were only attended by the nobility of that country. The historian Janet Nelson says that "Æthelwulf ran a Carolingian-style family firm of plural realms, held together by his own authority as father-king, and by the consent of distinct élites." He maintained his father's policy of governing Kent through ealdormen appointed from the local nobility and advancing their interests, but gave less support to the church.[40] In 843 Æthelwulf granted ten hides at Little Chart to Æthelmod, the brother of the leading Kentish ealdorman Ealhere, and Æthelmod succeeded to the post on his brother's death in 853.[41] In 844 Æthelwulf granted land at Horton in Kent to Ealdorman Eadred, with permission to transfer parts of it to local landowners; in a culture of reciprocity, this created a network of mutual friendships and obligations between the beneficiaries and the king.[42] Archbishops of Canterbury were firmly in the West Saxon king's sphere. His ealdormen enjoyed a high status, and were sometimes placed higher than the king's sons in lists of witnesses to charters.[43] His reign is the first for which there is evidence of royal priests,[44] and Malmesbury Abbey regarded him as an important benefactor, who is said to have been the donor of a shrine for the relics of Saint Aldhelm.[45]

After 830, Ecgberht had followed a policy of maintaining good relations with Mercia, and this was continued by Æthelwulf when he became king. London was traditionally a Mercian town, but in the 830s it was under West Saxon control; soon after Æthelwulf's accession it reverted to Mercian control.[46] King Wiglaf of Mercia died in 839 and his successor, Berhtwulf, revived the Mercian mint in London; the two kingdoms appear to have struck a joint issue in the mid-840s, possibly indicating West Saxon help in reviving Mercian coinage, and showing the friendly relations between the two powers. Berkshire was still Mercian in 844, but by 849 it was part of Wessex, as Alfred was born in that year at the West Saxon royal estate in Wantage, then in Berkshire.[47][lower-alpha 9] However, the local Mercian ealdorman, also called Æthelwulf, retained his position under the West Saxon kings.[49] Berhtwulf died in 852 and cooperation with Wessex continued under Burgred, his successor as King of Mercia, who married Æthelwulf's daughter Æthelswith in 853. In the same year Æthelwulf assisted Burgred in a successful attack on Wales to restore the traditional Mercian hegemony over the Welsh.[50]

In 9th-century Mercia and Kent, royal charters were produced by religious houses, each with its own style, but in Wessex there was a single royal diplomatic tradition, probably by a single agency acting for the king. This may have originated in Ecgberht's reign, and it becomes clear in the 840s, when Æthelwulf had a Frankish secretary called Felix.[51] There were strong contacts between the West Saxon and Carolingian courts. The Annals of St Bertin took particular interest in Viking attacks on Britain, and in 852 Lupus, the Abbot of Ferrières and a protégé of Charles the Bald, wrote to Æthelwulf congratulating him on his victory over the Vikings and requesting a gift of lead to cover his church roof. Lupus also wrote to his "most beloved friend" Felix, asking him to manage the transport of the lead.[52] Unlike Canterbury and the south-east, Wessex did not see a sharp decline in the standard of Latin in charters in the mid-9th century, and this may have been partly due to Felix and his continental contacts.[53] Lupus thought that Felix had great influence over the King.[13] Charters were mainly issued from royal estates in counties which were the heartland of ancient Wessex, namely Hampshire, Somerset, Wiltshire and Dorset, with a few in Kent.[54]

An ancient division between east and west Wessex continued to be important in the 9th century; the boundary was Selwood Forest on the borders of Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire. The two bishoprics of Wessex were Sherborne in the west and Winchester in the east. Æthelwulf's family connections seem to have been west of Selwood, but his patronage was concentrated further east, particularly on Winchester, where his father was buried, and where he appointed Swithun to succeed Helmstan as bishop in 852–853. However, he made a grant of land in Somerset to his leading ealdorman, Eanwulf, and on 26 December 846, he granted a large estate to himself in South Hams in west Devon. He thus changed it from royal demesne, which he was obliged to pass on to his successor as king, to bookland, which could be transferred as the owner pleased, so he could make land grants to followers to improve security in a frontier zone.[55]

Viking threat

Viking raids increased in the early 840s on both sides of the English Channel, and in 843 Æthelwulf was defeated by the companies of 35 Danish ships at Carhampton in Somerset. In 850 sub-king Æthelstan and Ealdorman Ealhhere of Kent won a naval victory over a large Viking fleet off Sandwich in Kent, capturing nine ships and driving off the rest. Æthelwulf granted Ealhhere a large estate in Kent, but Æthelstan is not heard of again, and probably died soon afterwards. The following year the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records five different attacks on southern England. A Danish fleet of 350 Viking ships took London and Canterbury, and when King Berhtwulf of Mercia went to their relief he was defeated. The Vikings then moved on to Surrey, where they were defeated by Æthelwulf and his son Æthelbald at the Battle of Aclea. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle the West Saxon levies "there made the greatest slaughter of a heathen that we have heard tell of up to the present day". The Chronicle frequently reported victories during Æthelwulf's reign won by levies led by ealdormen, unlike the 870s when royal command was emphasised, reflecting a more consensual style of leadership in the earlier period.[56]

In 850, a Danish army wintered on Thanet, and in 853, ealdormen Ealhhere of Kent and Huda of Surrey were killed in a battle against the Vikings, also on Thanet. In 855, Danish Vikings stayed over the winter on Sheppey, before carrying on their pillaging of eastern England.[57] However, during Æthelwulf's reign, Viking attacks were contained and did not present a major threat.[58]

Coinage

The silver penny was almost the only coin used in middle and later Anglo-Saxon England. Æthelwulf's coinage came from a main mint in Canterbury and a secondary one at Rochester; both had been used by Ecgberht for his own coinage after he gained control of Kent. During Æthelwulf's reign, there were four main phases of the coinage distinguishable at both mints, though they are not exactly parallel and it is uncertain when the transitions took place. The first issue at Canterbury carried a design known as Saxoniorum, which had been used by Ecgberht for one of his own issues. This was replaced by a portrait design in about 843, which can be subdivided further; the earliest coins have cruder designs than the later ones. At the Rochester mint, the sequence was reversed, with an initial portrait design replaced, also in about 843, by a non-portrait design carrying a cross-and-wedges pattern on the obverse.[13][60]

In about 848, both mints switched to a common design known as Dor¯b¯/Cant – the characters "Dor¯b¯" on the obverse of these coins indicate either Dorobernia (Canterbury) or Dorobrevia (Rochester), and "Cant", referring to Kent, appeared on the reverse. It is possible that the Canterbury mint continued to produce portrait coins at the same time. The Canterbury issue seems to have been ended in 850–851 by Viking raids, though it is possible that Rochester was spared, and the issue may have continued there. The final issue, again at both mints, was introduced in about 852; it has an inscribed cross on the reverse and a portrait on the obverse. Æthelwulf's coinage became debased by the end of his reign, and though the problem became worse after his death it is possible that the debasement prompted the changes in coin type from as early as 850.[61]

Æthelwulf's first Rochester coinage may have begun when he was still sub-king of Kent, under Ecgberht. A hoard of coins deposited at the beginning of Æthelwulf's reign in about 840, found in the Middle Temple in London, contained 22 coins from Rochester and two from Canterbury of the first issue of each mint. Some numismatists argue that the high proportion of Rochester coins means that the issue must have commenced before Ecgberht's death, but an alternative explanation is that whoever hoarded the coins simply happened to have access to more Rochester coins. No coins were issued by Æthelwulf's sons during his reign.[62]

Ceolnoth, Archbishop of Canterbury throughout Æthelwulf's reign, also minted coins of his own at Canterbury: there were three different portrait designs, thought to be contemporary with each of the first three of Æthelwulf's Canterbury issues. These were followed by an inscribed cross design that was uniform with Æthelwulf's final coinage. At Rochester, Bishop Beornmod produced only one issue, a cross-and-wedges design which was contemporary with Æthelwulf's Saxoniorum issue.[63]

In the view of the numismatists Philip Grierson and Mark Blackburn, the mints of Wessex, Mercia and East Anglia were not greatly affected by changes in political control: "the remarkable continuity of moneyers which can be seen at each of these mints suggests that the actual mint organisation was largely independent of the royal administration and was founded in the stable trading communities of each city".[64]

Decimation Charters

The early 20th-century historian W. H. Stevenson observed that: "Few things in our early history have led to so much discussion" as Æthelwulf's Decimation Charters;[66] a hundred years later the charter expert Susan Kelly described them as "one of the most controversial groups of Anglo-Saxon diplomas".[67] Both Asser and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle say that Æthelwulf gave a decimation,[lower-alpha 10] in 855, shortly before leaving on pilgrimage to Rome. According to the Chronicle "King Æthelwulf conveyed by charter the tenth part of his land throughout all his kingdom to the praise of God and to his own eternal salvation". However, Asser states that "Æthelwulf, the esteemed king, freed the tenth part of his whole kingdom from royal service and tribute, and as an everlasting inheritance he made it over on the cross of Christ to the triune God, for the redemption of his soul and those of his predecessors."[69] According to Keynes, Asser's version may just be a "loose translation" of the Chronicle, and his implication that Æthelwulf released a tenth of all land from secular burdens was probably not intended. All land could be regarded as the king's land, so the Chronicle reference to "his land" does not necessarily refer to royal property, and since the booking of land – conveying it by charter – was always regarded as a pious act, Asser's statement that he made it over to God does not necessarily mean that the charters were in favour of the church.[70]

The Decimation Charters are divided by Susan Kelly into four groups:

- Two dated at Winchester on 5 November 844. In a charter in the Malmesbury archive, Æthelwulf refers in the proem to the perilous state of his kingdom as the result of the assaults of pagans and barbarians. For the sake of his soul and in return for masses for the king and ealdormen each Wednesday, "I have decided to give in perpetual liberty some portion of hereditary lands to all those ranks previously in possession, both to God's servants and handmaidens serving God and to laymen, always the tenth hide, and where it is less, then the tenth part."[lower-alpha 11]

- Six dated at Wilton on Easter Day, 22 April 854. In the common text of these charters, Æthelwulf states that "for the sake of his soul and the prosperity of the kingdom and [the salvation of] the people assigned to him by God, he has acted upon the advice given to him by his bishops, comites, and all his nobles. He has granted the tenth part of the lands throughout his kingdom, not only to the churches, but also to his thegns. The land is granted in perpetual liberty, so that it will remain free of royal services and all secular burdens. In return there will be liturgical commemoration of the king and of his bishops and ealdormen."[lower-alpha 12]

- Five from Old Minster, Winchester, connected with the Wilton meeting but generally considered spurious.[lower-alpha 13]

- One from Kent dated 855, the only one to have the same date as the decimation according to Chronicle and Asser. The king grants to his thegn Dunn property in Rochester "on account of the decimation of lands which by God's gift I have decided to do". Dunn left the land to his wife with reversion to Rochester Cathedral.[lower-alpha 14][73]

None of the charters are original, and Stevenson dismissed all of them as fraudulent apart from the Kentish one of 855. Stevenson saw the decimation as a donation of royal demesne to churches and laymen, with those grants which were made to laymen being on the understanding that there would be reversion to a religious institution.[74] Up to the 1990s, his view on the authenticity of the charters was generally accepted by scholars, with the exception of the historian H. P. R. Finberg, who argued in 1964 that most are based on authentic diplomas. Finberg coined the terms the 'First Decimation' of 844, which he saw as the removal of public dues on a tenth of all bookland, and the 'Second Decimation' of 854, the donation of a tenth of "the private domain of the royal house" to the churches. He considered it unlikely that the First Decimation had been carried into effect, probably due to the threat from the Vikings. Finberg's terminology has been adopted, but his defence of the First Decimation generally rejected. In 1994, Keynes defended the Wilton charters in group 2, and his arguments have been widely accepted.[75]

Historians have been divided on how to interpret the Second Decimation, and in 1994, Keynes described it as "one of the most perplexing problems" in the study of 9th-century charters. He set out three alternatives:

- It conveyed a tenth of the royal demesne – the lands of the crown as opposed to the personal property of the sovereign – into the hands of churches, ecclesiastics and laymen. In Anglo-Saxon England property was either folkland or bookland. The transmission of folkland was governed by the customary rights of kinsmen, subject to the king's approval, whereas bookland was established by the grant of a royal charter, and could be disposed of freely by the owner. Booking land thus converted it by charter from folkland to bookland. The royal demesne was the crown's folkland, whereas the king's bookland was his own personal property which he could leave by will as he chose. In the decimation, Æthelwulf may have conveyed royal folkland by charter to become bookland, in some cases to laymen who already leased the land.[76]

- It was the booking of a tenth of folkland to its owners, who would then be free to convey it to a church.[77]

- It was a reduction of one tenth in the secular burdens on lands already in the possession of landowners.[77] The secular burdens would have included the provision of supplies for the king and his officials, and payment of various taxes.[78]

Some scholars, for example Frank Stenton, author of the standard history of Anglo-Saxon England, along with Keynes and Abels, see the Second Decimation as a donation of royal demesne. In Abels' view, Æthelwulf sought loyalty from the aristocracy and church during the king's forthcoming absence from Wessex, and displayed a sense of dynastic insecurity also evident in his father's generosity towards the Kentish church in 838, and in an "avid attention" in this period to compiling and revising royal genealogies.[79] Keynes suggests that "Æthelwulf's purpose was presumably to earn divine assistance in his struggles against the Vikings",[80] and the mid-20th-century historian Eric John observes that "a lifetime of medieval studies teaches one that an early medieval king was never so political as when he was on his knees".[81] The view that the decimation was a donation of the king's own personal estate is supported by the Anglo-Saxonist Alfred P. Smyth, who argues that these were the only lands the king was entitled to alienate by book.[82][lower-alpha 15] The historian Martin Ryan prefers the view that Æthelwulf freed a tenth part of land owned by laymen from secular obligations, who could now endow churches under their own patronage. Ryan sees it as part of a campaign of religious devotion.[85] According to the historian David Pratt, it "is best interpreted as a strategic 'tax cut', designed to encourage cooperation in defensive measures through a partial remission of royal dues".[86] Nelson states that the decimation took place in two phases, in Wessex in 854 and Kent in 855, reflecting that they remained separate kingdoms.[87]

Kelly argues that most charters were based on genuine originals, including the First Decimation of 844. She says: "Commentators have been unkind [and] the 844 version has not been given the benefit of the doubt". In her view, Æthelwulf then gave a 10% tax reduction on bookland, and ten years later he took the more generous step of "a widespread distribution of royal lands". Unlike Finberg, she believes that both decimations were carried out, although the second one may not have been completed due to opposition from Æthelwulf's son Æthelbald. She thinks that the grants of bookland to laymen in the Second Decimation were unconditional, not with reversion to religious houses as Stevenson had argued.[88] However, Keynes is not convinced by Kelly's arguments, and thinks that the First Decimation charters were 11th or early 12th century fabrications.[89]

Pilgrimage to Rome and later life

In 855, Æthelwulf went on pilgrimage to Rome. According to Abels: "Æthelwulf was at the height of his power and prestige. It was a propitious time for the West Saxon king to claim a place of honour among the kings and emperors of christendom."[90] His eldest surviving sons Æthelbald and Æthelberht were then adults, while Æthelred and Alfred were still young children. In 853 Æthelwulf sent his younger sons to Rome, perhaps accompanying envoys in connection with his own forthcoming visit. Alfred, and probably Æthelred as well, were invested with the "belt of consulship". Æthelred's part in the journey is only known from a contemporary record in the liber vitae of San Salvatore, Brescia, as later records such as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle were only interested in recording the honour paid to Alfred.[13] Abels sees the embassy as paving the way for Æthelwulf's pilgrimage, and the presence of Alfred, his youngest and therefore most expendable son, as a gesture of goodwill to the papacy; confirmation by Pope Leo IV made Alfred his spiritual son, and thus created a spiritual link between the two "fathers".[91][lower-alpha 16] Kirby argues that the journey may indicate that Alfred was intended for the church,[93] while Nelson on the contrary sees Æthelwulf's purpose as affirming his younger sons' throneworthiness, thus protecting them against being tonsured by their elder brothers, which would have rendered them ineligible for kingship.[94]

Æthelwulf set out for Rome in the spring of 855, accompanied by Alfred and a large retinue.[95] The King left Wessex in the care of his oldest surviving son, Æthelbald, and the sub-kingdom of Kent to the rule of Æthelberht, and thereby confirmed that they were to succeed to the two kingdoms.[25] On the way the party stayed with Charles the Bald in Francia, where there were the usual banquets and exchange of gifts. Æthelwulf stayed a year in Rome,[96] and his gifts to the Diocese of Rome included a gold crown weighing 4 pounds (1.8 kg), two gold goblets, a sword bound with gold, four silver-gilt bowls, two silk tunics and two gold-interwoven veils. He also gave gold to the clergy and leading men and silver to the people of Rome. According to the historian Joanna Story, his gifts rivalled those of Carolingian donors and the Byzantine emperor and "were clearly chosen to reflect the personal generosity and spiritual wealth of the West Saxon king; here was no Germanic 'hillbilly' from the backwoods of the Christian world but, rather, a sophisticated, wealthy and utterly contemporary monarch".[97] The post-Conquest chronicler William of Malmesbury stated that he helped to pay for the restoration of the Saxon quarter, which had recently been destroyed by fire, for English pilgrims.[98]

The pilgrimage puzzles historians and Kelly comments that "it is extraordinary that an early medieval king could consider his position safe enough to abandon his kingdom in a time of extreme crisis". She suggests that Æthelwulf may have been motivated by a personal religious impulse.[99] Ryan sees it as an attempt to placate the divine wrath displayed by Viking attacks,[85] whereas Nelson thinks he aimed to enhance his prestige in dealing with the demands of his adult sons.[100] In Kirby's view:

Æthelwulf's journey to Rome is of great interest for it did not signify abdication and a retreat from the world as their journeys to Rome had for Cædwalla and Ine and other Anglo-Saxon kings. It was more a display of the king's international standing and a demonstration of the prestige his dynasty enjoyed in Frankish and papal circles.[101]

On his way back from Rome Æthelwulf again stayed with King Charles the Bald, and may have joined him on a campaign against a Viking warband.[102] On 1 October 856 Æthelwulf married Charles's daughter, Judith, aged 12 or 13, at Verberie. The marriage was considered extraordinary by contemporaries and by modern historians. Carolingian princesses rarely married and were usually sent to nunneries, and it was almost unknown for them to marry foreigners. Judith was crowned queen and anointed by Hincmar, Archbishop of Rheims. Although empresses had been anointed before, this is the first definitely known anointing of a Carolingian queen. In addition West Saxon custom, described by Asser as "perverse and detestable", was that the wife of a king of Wessex could not be called queen or sit on the throne with her husband – she was just the king's wife.[103]

Æthelwulf returned to Wessex to face a revolt by Æthelbald, who attempted to prevent his father from recovering his throne. Historians give varying explanations for both the rebellion and the marriage. In Nelson's view, Æthelwulf's marriage to Judith added the West Saxon king to the family of kings and princely allies which Charles was creating.[104] Charles was under attack both from Vikings and from a rising among his own nobility, and Æthelwulf had great prestige due to his victories over the Vikings; some historians such as Kirby and Pauline Stafford see the marriage as sealing an anti-Viking alliance. The marriage gave Æthelwulf a share in Carolingian prestige, and Kirby describes the anointing of Judith as "a charismatic sanctification which enhanced her status, blessed her womb and conferred additional throne-worthiness on her male offspring." These marks of a special status implied that a son of hers would succeed to at least part of Æthelwulf's kingdom, and explain Æthelbald's decision to rebel.[105] The historian Michael Enright denies that an anti-Viking alliance between two such distant kingdoms could serve any useful purpose, and argues that the marriage was Æthelwulf's response to news that his son was planning to rebel; his son by an anointed Carolingian queen would be in a strong position to succeed as king of Wessex instead of the rebellious Æthelbald.[106] Abels suggests that Æthelwulf sought Judith's hand because he needed her father's money and support to overcome his son's rebellion,[107] but Kirby and Smyth argue that it is extremely unlikely that Charles the Bald would have agreed to marry his daughter to a ruler who was known to be in serious political difficulty.[108] Æthelbald may also have acted out of resentment at the loss of patrimony he suffered as a result of the decimation.[99]

Æthelbald's rebellion was supported by Ealhstan, Bishop of Sherborne, and Eanwulf, ealdorman of Somerset, even though they appear to have been two of the king's most trusted advisers.[109] According to Asser, the plot was concerted "in the western part of Selwood", and western nobles may have backed Æthelbald because they resented the patronage Æthelwulf gave to eastern Wessex.[110] Asser also stated that Æthelwulf agreed to give up the western part of his kingdom in order to avoid a civil war. Some historians such as Keynes and Abels think that his rule was then confined to the south-east,[111] while others such as Kirby think it is more likely that it was Wessex itself which was divided, with Æthelbald keeping Wessex west of Selwood, Æthelwulf holding the centre and east, and Æthelberht keeping the south-east.[112] Æthelwulf insisted that Judith should sit beside him on the throne until the end of his life, and according to Asser this was "without any disagreement or dissatisfaction on the part of his nobles".[113]

King Æthelwulf's ring

King Æthelwulf's ring was found in a cart rut in Laverstock in Wiltshire in about August 1780 by one William Petty, who sold it to a silversmith in Salisbury. The silversmith sold it to the Earl of Radnor, and the earl's son, William, donated it to the British Museum in 1829. The ring, together with a similar ring of Æthelwulf's daughter Æthelswith, is one of two key examples of nielloed 9th-century metalwork. They appear to represent the emergence of a "court style" of West Saxon metalwork, characterised by an unusual Christian iconography, such as a pair of peacocks at the Fountain of Life on the Æthelwulf ring, associated with Christian immortality. The ring is inscribed "Æthelwulf Rex", firmly associating it with the King, and the inscription forms part of the design, so it cannot have been added later. Many of its features are typical of 9th-century metalwork, such as the design of two birds, beaded and speckled borders, and a saltire with arrow-like terminals on the back. It was probably manufactured in Wessex, but was typical of the uniformity of animal ornament in England in the 9th century. In the view of Leslie Webster, an expert on medieval art: "Its fine Trewhiddle style ornament would certainly fit a mid ninth-century date."[114] In Nelson's view, "it was surely made to be a gift from this royal lord to a brawny follower: the sign of a successful ninth-century kingship".[13] The art historian David Wilson sees it as a survival of the pagan tradition of the generous king as the "ring-giver".[115]

Æthelwulf's will

Æthelwulf's will has not survived, but Alfred's has and it provides some information about his father's intentions. He left a bequest to be inherited by whichever of Æthelbald, Æthelred, and Alfred lived longest. Abels and Yorke argue that this meant the whole of his personal property in Wessex, and probably that the survivor was to inherit the throne of Wessex as well, while Æthelberht and his heirs ruled Kent.[116] Other historians disagree. Nelson states that the provision regarding the personal property had nothing to do with the kingship,[13] and Kirby comments: "Such an arrangement would have led to fratricidal strife. With three older brothers, Alfred's chances of reaching adulthood would, one feels, have been minimal."[117] Smyth describes the bequest as provision for his youngest sons when they reached manhood.[118] Æthelwulf's moveable wealth, such as gold and silver, was to be divided among "children, nobles and the needs of the king's soul".[13] For the latter, he left one tenth of his hereditary land to be set aside to feed the poor, and he ordered that three hundred mancuses be sent to Rome each year, one hundred to be spent on lighting the lamps in St Peter's at Easter, one hundred for the lights of St Paul's, and one hundred for the pope.[119]

Death and succession

Æthelwulf died on 13 January 858. According to the Annals of St Neots, he was buried at Steyning in Sussex, but his body was later transferred to Winchester, probably by Alfred.[120][lower-alpha 17] As Æthelwulf had intended, he was succeeded by Æthelbald in Wessex and Æthelberht in Kent and the south-east.[122] The prestige conferred by a Frankish marriage was so great that Æthelbald then wedded his step-mother Judith, to Asser's retrospective horror; he described the marriage as a "great disgrace", and "against God's prohibition and Christian dignity".[13] When Æthelbald died only two years later, Æthelberht became King of Wessex as well as Kent, and Æthelwulf's intention of dividing his kingdoms between his sons was thus set aside. In the view of Yorke and Abels, this was because Æthelred and Alfred were too young to rule, and Æthelberht agreed in return that his younger brothers would inherit the whole kingdom on his death,[123] whereas Kirby and Nelson think that Æthelberht just became the trustee for his younger brothers' share of their father's bequest.[124]

After Æthelbald's death, Judith sold her possessions and returned to her father, but two years later she eloped with Baldwin, Count of Flanders. In the 890s their son, also called Baldwin, married Alfred's daughter, Ælfthryth.[13]

Historiography

Æthelwulf's reputation among historians was poor in the twentieth century. In 1935, the historian R. H. Hodgkin attributed his pilgrimage to Rome to "the unpractical piety which had led him to desert his kingdom at a time of great danger", and described his marriage to Judith as "the folly of a man senile before his time".[125] To Stenton in the 1960s, he was "a religious and unambitious man, for whom engagement in war and politics was an unwelcome consequence of rank".[126] One dissenter was Finberg, who in 1964 described him as "a king whose valour in war and princely munificence recalled the figures of the heroic age",[127] but in 1979, Enright said: "More than anything else he appears to have been an impractical religious enthusiast."[128] Early medieval writers, especially Asser, emphasise his religiosity and his preference for consensus, seen in the concessions made to avert a civil war on his return from Rome.[lower-alpha 18] In Story's view, "his legacy has been clouded by accusations of excessive piety which (to modern sensibilities at least) has seemed at odds with the demands of early medieval kingship". In 839, an unnamed Anglo-Saxon king wrote to the Holy Roman Emperor Louis the Pious asking for permission to travel through his territory on the way to Rome, and relating an English priest's dream which foretold disaster unless Christians abandoned their sins. This is now believed to have been an unrealised project of Ecgberht at the end of his life, but it was formerly attributed to Æthelwulf, and seen as exhibiting what Story calls his reputation for "dramatic piety", and irresponsibility for planning to abandon his kingdom at the beginning of his reign.[130]

In the twenty-first century, he is seen very differently by historians. Æthelwulf is not listed in the index of Peter Hunter Blair's An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England, first published in 1956, but in a new introduction to the 2003 edition, Keynes listed him among people "who have not always been accorded the attention they might be thought to deserve ... for it was he, more than any other, who secured the political fortune of his people in the ninth century, and who opened up channels of communication which led through Frankish realms and across the Alps to Rome".[131] According to Story: "Æthelwulf acquired and cultivated a reputation both in Francia and Rome which is unparalleled in the sources since the height of Offa's and Coenwulf's power at the turn of the ninth century".[132]

Nelson describes him as "one of the great underrated among Anglo-Saxons", and complains that she was only allowed 2,500 words for him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, compared with 15,000 for Edward II and 35,000 for Elizabeth I.[133] She says:

Æthelwulf's reign has been relatively under-appreciated in modern scholarship. Yet he laid the foundations for Alfred's success. To the perennial problems of husbanding the kingdom's resources, containing conflicts within the royal family, and managing relations with neighbouring kingdoms, Æthelwulf found new as well as traditional answers. He consolidated old Wessex, and extended his reach over what is now Devon and Cornwall. He ruled Kent, working with the grain of its political community. He borrowed ideological props from Mercians and Franks alike, and went to Rome, not to die there, like his predecessor Ine, ... but to return, as Charlemagne had, with enhanced prestige. Æthelwulf coped more effectively with Scandinavian attacks than did most contemporary rulers.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Ecgberht's death and Æthelwulf's accession are dated by historians to 839. According to Susan Kelly, "there may be grounds for arguing that Æthelwulf's succession actually took place late in 838",[3] but Joanna Story argues that the West Saxon regnal lists show the length of Ecgberht's reign as 37 years and 7 months, and as he acceded in 802 he is unlikely to have died before July 839.[4]

- ↑ Keynes and Lapidge comment: "The office of butler (pincerna) was a distinguished one, and its holders were likely to have been important figures in the royal court and household".[12]

- ↑ Æthelstan was sub-king of Kent ten years before Alfred was born, and some late versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle make him the brother of Æthelwulf rather than his son. This has been accepted by some historians, but is now generally rejected. It has also been suggested that Æthelstan was born of an unrecorded first marriage, but historians generally assume that he was Osburh's son.[15]

- ↑ Nelson states that it is uncertain whether Osburh died or had been repudiated,[13] but Abels argues that it is "extremely unlikely" that she was repudiated, as Hincmar of Rheims, who played a prominent role in Æthelwulf's and Judith's marriage ceremony, was a strong advocate of the indissolubility of marriage.[18]

- ↑ The historians Janet Nelson and Ann Williams date Baldred's removal and the start of Æthelwulf's sub-kingship to 825,[19] but David Kirby states that Baldred was probably not driven out until 826.[20] Simon Keynes cites the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as stating that Æthelwulf expelled Baldred in 825, and secured the submission of the people of Kent, Surrey, Sussex and Essex; however, charter evidence suggests that Beornwulf was recognised as overlord of Kent until he was killed in battle while attempting to put down a rebellion in East Anglia in 826. His successor as king of Mercia, Ludeca, never seems to have been recognised in Kent. In a charter of 828 Ecgberht refers to his son Æthelwulf "whom we have made king in Kent" as if the appointment was fairly new.[21]

- ↑ Christ Church, Canterbury kept lists of patrons who had made donations to the church, and late 8th and early 9th century patrons who had been supporters of Mercian power were expunged from the lists towards the end of the 9th century.[26]

- ↑ The authenticity of the Winchester charter is accepted by Patrick Wormald and Nicholas Brooks but disputed by Simon Keynes.[32]

- ↑ To attest a charter was to witness a grant of land by the king. The attesters were listed by the scribe at the end of the charter, although usually only the most high-ranking witnesses were included.

- ↑ The scholar James Booth suggests that the part of Berkshire where Alfred was born may have been West Saxon territory throughout the period.[48]

- ↑ "Decimation" is used here in the sense of a donation of a tenth part. This usually means a payment to the ruler or church (tithe),[68] but it is used here to mean a donation of a tenth part by the king. Historians do not agree what it was a tenth of.

- ↑ The charters are S 294, 294a and 294b. Kelly treats 294a and b, which are both from Malmesbury Abbey, as one text.[71]

- ↑ The six charters are S 302, 303, 304, 305, 307 and 308.[72]

- ↑ The five Old Minster charters are S 309–313. Kelly states that there are six charters, but she only lists five and she states that there are fourteen in total, whereas there would be fifteen if there were six Old Minster charters.[67]

- ↑ The Kent charter is S 315.[67]

- ↑ Smyth dismisses all the Decimation Charters as spurious,[83] with what the scholar David Pratt describes as "unwarranted scepticism".[84]

- ↑ Abels is sceptical whether Æthelred accompanied Alfred to Rome as he is not mentioned in a letter from Leo to Æthelwulf reporting Alfred's reception,[92] but Nelson argues that only a fragment of the letter survives in an 11th-century copy, and the scribe who selected excerpts from Leo's letters, like the editors of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, was only interested in Alfred.[13]

- ↑ Some of Æthelwulf's bones may be in Winchester Cathedral. One of six mortuary chests near the altar has his name, but the bones were mixed up when they were thrown around by parliamentary soldiers during the English Civil War.[121]

- ↑ The historian Richard North argues that the Old English poem "Deor" was written in about 856 as a satire on Æthelwulf and a "mocking reflection" on Æthelbald's attitude towards him.[129]

Citations

- ↑ Jones 2011, p. 171.

- ↑ Halsall 2013, p. 288.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, p. 178.

- ↑ Story 2003, p. 222, n. 39.

- ↑ Keynes 1995, pp. 22, 30–37; Williams 1991b; Kirby 2000, p. 152.

- ↑ Abels 2002, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Edwards 2004.

- ↑ Abels 2002, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 113–19; Brooks 1984, pp. 132–36.

- ↑ Ryan 2013, p. 258; Stenton 1971, p. 241.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 235; Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 431.

- ↑ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 229–30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Nelson 2004a.

- ↑ Nelson 2004b.

- ↑ Hodgkin 1935, pp. 497, 721; Stenton 1971, p. 236, n. 1; Abels 1998, p. 50; Nelson 2004b.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 50.

- ↑ Miller 2004.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 71, n. 69.

- ↑ Nelson 2004a; Williams 1991a.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 155–56.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 120–21.

- ↑ Williams 1991a; Stenton 1971, p. 231; Kirby 2000, pp. 155–56.

- ↑ Smyth 1995, p. 673, n. 63.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 112–20.

- 1 2 Abels 2002, p. 88.

- ↑ Fleming 1995, p. 75.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 120–21; Keynes 1995, p. 40.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 136–37.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, pp. 232–33.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 157.

- ↑ Keynes 1995, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Wormald 1982, p. 140; Brooks 1984, p. 200; Keynes 1994, p. 1114 n. 3; S 281.

- ↑ Wormald 1982, p. 140; Keynes 1994, pp. 1112–13.

- ↑ Nelson 2004a; Keynes 1993, p. 124; Brooks 1984, pp. 197–201; Story 2003, p. 223; Blair 2005, p. 124.

- ↑ Yorke 1990, pp. 148–49.

- ↑ Pratt 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, p. 89.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 28.

- ↑ Yorke 1990, pp. 168–69.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 124–27; Nelson 2004a.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 147–49.

- ↑ Abels 1998, pp. 32–33; S 319.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 271.

- ↑ Pratt 2007, p. 64.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 13, 102.

- ↑ Keynes 1993, pp. 127–28.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 160–61; Keynes 1998, p. 6; Booth 1998, p. 65.

- ↑ Booth 1998, p. 66.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 29.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 161.

- ↑ Keynes 1994, pp. 1109–23; Nelson 2004a.

- ↑ Nelson 2013, pp. 236–38; Stafford 1981, p. 137.

- ↑ Ryan 2013, p. 252.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 52.

- ↑ Yorke 1995, pp. 23–24, 98–99; Nelson 2004a; Finberg 1964, p. 189.

- ↑ Nelson 2004a; Story 2003, p. 227.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 243; Abels 1998, p. 88.

- ↑ Ryan 2013, p. 258.

- ↑ Grueber & Keary 1893, pp. 9, 17 no. 19, Plate III.4; Early Medieval Coins & Fitzwilliam Museum.

- ↑ Grierson & Blackburn 2006, pp. 270, 287–91.

- ↑ Grierson & Blackburn 2006, pp. 287–91, 307–08.

- ↑ Grierson & Blackburn 2006, pp. 271, 287–91.

- ↑ Grierson & Blackburn 2006, pp. 287–91.

- ↑ Grierson & Blackburn 2006, p. 275.

- ↑ S 316.

- ↑ Stevenson 1904, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 Kelly 2005, p. 65.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary 1933.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Keynes 1994, pp. 1119–20.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 65, 180.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 65, 188.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 65–67, 73–74, 80–81.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, p. 65; Stevenson 1904, pp. 186–91.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 65–67; Finberg 1964, pp. 187–206; Keynes 1994, pp. 1102–22; Nelson 2004c, p. 15; Pratt 2007, p. 66.

- ↑ Keynes 1994, pp. 1119–21; Williams 2014; Wormald 2001, p. 267; Keynes 2009, p. 467; Nelson 2004c, p. 3.

- 1 2 Keynes 1994, pp. 1119–21.

- ↑ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, p. 232.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 308; Abels 2002, pp. 88–89; Keynes 2009, p. 467.

- ↑ Keynes 2009, p. 467.

- ↑ John 1996, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Smyth 1995, p. 403.

- ↑ Smyth 1995, pp. 376–78, 382–83.

- ↑ Pratt 2007, p. 66, n. 20.

- 1 2 Ryan 2013, p. 255.

- ↑ Pratt 2007, p. 68.

- ↑ Nelson 2004c, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Kelly 2005, pp. 67–91.

- ↑ Keynes 2009, pp. 464–67.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 62.

- ↑ Abels 1998, pp. 62, 67.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 67, n. 57.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 164–65.

- ↑ Nelson 1997, pp. 144–46; Nelson 2004a.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 72.

- ↑ Abels 1998, pp. 73, 75.

- ↑ Story 2003, pp. 238–39.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 77.

- 1 2 Kelly 2005, p. 91.

- ↑ Nelson 2013, p. 240.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 164.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 79.

- ↑ Stafford 1981, pp. 139–42; Story 2003, pp. 240–42.

- ↑ Nelson 1997, p. 143.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 165–66; Stafford 1981, p. 139.

- ↑ Enright 1979, pp. 291–301.

- ↑ Abels 1998, pp. 80–82; Enright 1979, pp. 291–302.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 166; Smyth 1995, pp. 191–92.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 81.

- ↑ Yorke 1995, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Keynes 1998, p. 7; Abels 2002, p. 89.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 166–67.

- ↑ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, pp. 71, 235–36, n. 28; Nelson 2006, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Wilson 1964, pp. 2, 22, 34, 142; Webster 1991, pp. 268–69; Pratt 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Wilson 1964, p. 22.

- ↑ Abels 2002, pp. 89–91; Yorke 1990, pp. 149–50.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, p. 167.

- ↑ Smyth 1995, pp. 416–17.

- ↑ Abels 1998, p. 87.

- ↑ Smyth 1995, p. 674, n. 81.

- ↑ Notes & Queries about the Mortuary Chests.

- ↑ Keynes & Lapidge 1983, p. 72.

- ↑ Yorke 1990, pp. 149–50; Abels 2002, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Kirby 2000, pp. 167–69; Nelson 2004a.

- ↑ Hodgkin 1935, pp. 514–15.

- ↑ Stenton 1971, p. 245.

- ↑ Finberg 1964, p. 193.

- ↑ Enright 1979, p. 295.

- ↑ O'Keeffe 1996, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Story 2003, pp. 218–28; Dutton 1994, pp. 107–09.

- ↑ Keynes 2003, p. xxxiii.

- ↑ Story 2003, p. 225.

- ↑ Nelson 2004c.

Sources

- Abels, Richard (1998). Alfred the Great: War, Kingship and Culture in Anglo-Saxon England. Harlow, UK: Longman. ISBN 0-582-04047-7.

- Abels, Richard (2002). Morillo, Stephen (ed.). "Royal Succession and the Growth of Political Stability in Ninth-Century Wessex". The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell & Brewer. 12: 83–97. doi:10.1017/upo9781846150852.006. ISBN 1-84383-008-6.

- Blair, John (2005). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Booth, James (1998). "Monetary Alliance or Technical Cooperation? The Coinage of Berhtwulf of Mercia (840–852)". In Blackburn, Mark A. S.; Dumville, David N. (eds.). Kings, Currency and Alliances: History and Coinage of Southern England in the Ninth Century. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 63–103. ISBN 0-85115-598-7.

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury. Leicester, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1182-4.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- "Decimation". The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 1971 [1933]. p. 661. OCLC 67218777.

- Dutton, Paul Edward (1994). The Politics of Dreaming in the Carolingian Empire. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1653-X.

- "Early Medieval Coins: EMC number 2001.0016". Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Edwards, Heather (2004). "Ecgberht [Egbert] (d. 839), king of the West Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8581. Retrieved 5 April 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Enright, Michael J. (1979). "Charles the Bald and Æthelwulf of Wessex: Alliance of 856 and Strategies of Royal Succession". Journal of Medieval History. Amsterdam, Netherlands: North Holland. 5 (1): 291–302. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(79)90003-4. ISSN 0304-4181.

- Finberg, H. P. R. (1964). The Early Charters of Wessex. Leicester, UK: Leicester University Press. OCLC 3977243.

- Fleming, Robin (1995). "History and Liturgy at Pre-Conquest Christ Church". The Haskins Society Journal: Studies in Medieval History. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. 6: 67–83. ISBN 0-85115-604-5.

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark (2006) [1986]. Medieval European Coinage, With A Catalogue of the Coins in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge: 1: The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th Centuries) (corr. ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-03177-X.

- Grueber, Herbert A.; Keary, Charles Francis (1893). A Catalogue of English Coins in the British Museum: Anglo-Saxon Series (PDF). Vol. 2. London, UK: Printed by Order of the Trustees. OCLC 650118125. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2012.

- Halsall, Guy (2013). Worlds of Arthur: Facts & Fictions in the Dark Ages. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870084-5.

- Hodgkin, R. H. (1935). A History of the Anglo-Saxons. Vol. 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. OCLC 1350966.

- John, Eric (1996). Reassessing Anglo-Saxon England. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5053-7.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- Kelly, Susan (2005). Charters of Malmesbury Abbey. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726317-4.

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael, eds. (1983). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and Other Contemporary Sources. London, UK: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Keynes, Simon (1993). "The Control of Kent in the Ninth Century". Early Medieval Europe. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 2 (2): 111–31. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.1993.tb00013.x. ISSN 1468-0254.

- Keynes, Simon (November 1994). "The West Saxon Charters of King Æthelwulf and his sons". English Historical Review. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 109 (434): 1109–49. doi:10.1093/ehr/cix.434.1109. ISSN 0013-8266.

- Keynes, Simon (1995). "England, 700–900". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2, c.700–c.900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–42. ISBN 978-1-13905571-0.

- Keynes, Simon (1998). "King Alfred and the Mercians". In Blackburn, Mark A. S.; Dumville, David N. (eds.). Kings, Currency and Alliances: History and Coinage of Southern England in the Ninth Century. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. pp. 1–45. ISBN 0-85115-598-7.

- Keynes, Simon (2003) [1955]. "Introduction: Changing Perceptions of Anglo-Saxon History". In Blair, Peter Hunter (ed.). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. xvii–xxxv. ISBN 0-521-83085-0.

- Keynes, Simon (2009). "King Æthelred's Charter for Eynsham Abbey (1005)". In Baxter, Stephen; Karkov, Catherine; Nelson, Janet L.; Pelteret, David (eds.). Early Medieval Studies in Memory of Patrick Wormald. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. pp. 451–73. ISBN 978-0-7546-6331-7.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings (Revised ed.). London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Miller, Sean (2004). "Æthelred I [Ethelred I] (d. 871), King of the West Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8913. Retrieved 24 March 2014. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Nelson, Janet L. (1997). "The Franks and the English in the Ninth Century Reconsidered". In Szarmach, Paul E.; Rosenthal, Joel T. (eds.). The Preservation and Transmission of Anglo-Saxon Culture: Selected Papers from the 1991 Meeting of the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists (PDF). Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University. pp. 141–58. ISBN 1-879288-90-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2017.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2004a). "Æthelwulf (d. 858), king of the West Saxons". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39264. Retrieved 8 March 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Nelson, Janet L. (2004b). "Osburh [Osburga] (fl. 839)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20887. Retrieved 8 March 2015. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Nelson, Janet L. (2004c). "England and the Continent in the Ninth Century: III, Rights and Rituals". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (14): 1–24.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2006). "The Queen in Ninth-Century Wessex". In Keynes, Simon; Smyth, Alfred P. (eds.). Anglo-Saxons: Studies Presented to Cyril Roy Hart. Dublin, Ireland: Four Courts Press. pp. 69–77. ISBN 1-85182-932-6.

- Nelson, Janet L. (2013). "Britain, Ireland, and Europe, c. 750–c.900". In Stafford, Pauline (ed.). A Companion to the Early Middle Ages: Britain and Ireland c.500–c.1100 (paperback ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 231–47. ISBN 978-1-118-42513-8.

- "Notes & Queries about the Mortuary Chests". Winchester Cathedral. Church Monuments Society. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- O'Keeffe, Katherine O'Brien (Winter 1996). "Deor" (PDF). Old English Newsletter. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University. 29 (2): 35–36. ISSN 0030-1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2015.

- Pratt, David (2007). The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12644-1.

- Ryan, Martin J. (2013). "The Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings, c. 825–900". In Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (eds.). The Anglo-Saxon World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 232–70. ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4.

- "S 281". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "S 316". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- "S 319". The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1995). King Alfred the Great. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822989-5.

- Stafford, Pauline (1981). "Charles the Bald, Judith and England". In Gibson, Margaret; Nelson, Janet L. (eds.). Charles the Bald: Court and Kingdom. Oxford, UK: B A R. pp. 137–51. ISBN 0-86054-115-0.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Stevenson, William Henry (1904). Asser's Life of King Alfred. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. OCLC 1354216.

- Story, Joanna (2003). Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, c. 750–870. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-0124-2.

- Webster, Leslie (1991). "The Age of Alfred: Metalwork, Wood and Bone". In Webster, Leslie; Backhouse, Janet (eds.). The Making of England: Anglo-Saxon Art and Culture AD 600–900. London, UK: The Trustees of the British Museum. pp. 268–83. ISBN 0-7141-0555-4.

- Williams, Ann (1991a). "Æthelwulf King of Wessex 839-58". In Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-1-85264-047-7.

- Williams, Ann (1991b). "Ecgberht King of Wessex 802–39". In Williams, Ann; Smyth, Alfred P.; Kirby, D. P. (eds.). A Biographical Dictionary of Dark Age Britain. London, UK: Seaby. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-85264-047-7.

- Williams, Ann (2014). "Land Tenure". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 282–83. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Wilson, David M. (1964). Anglo-Saxon Ornamental Metalwork 700–1100 in the British Museum. London, UK: The Trustees of the British Museum. OCLC 183495.

- Wormald, Patrick (1982). "The Ninth Century". In Campbell, James (ed.). The Anglo-Saxons. London, UK: Penguin Books. pp. 132–59. ISBN 978-0-7148-2149-8.

- Wormald, Patrick (2001). "Kingship and Royal Property from Æthelwulf to Edward the Elder". In Higham, N. J.; Hill, D. H. (eds.). Edward the Elder 899–924. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 264–79. ISBN 0-415-21497-1.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

- Yorke, Barbara (1995). Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. London, UK: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1856-X.