Khujand

| |

|---|---|

| |

Flag  Seal | |

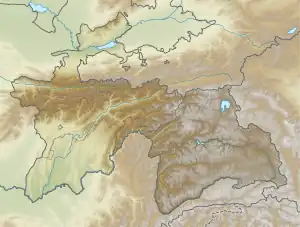

Khujand Location in Tajikistan  Khujand Khujand (West and Central Asia)  Khujand Khujand (Hindu-Kush) | |

| Coordinates: 40°17′N 69°38′E / 40.283°N 69.633°E | |

| Country | Tajikistan |

| Province | Sughd |

| Area | |

| • City | 40 km2 (20 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2 651.7 km2 (1 023.8 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 300 m (1,000 ft) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • City | 191,000 |

| • Urban | 770,000 |

| • Metro | 1,001,700 |

| Time zone | UTC+5 |

| Area code | 00 992 3422 |

| Official languages | |

| Website | www |

Khujand (Tajik: Хуҷанд; Russian: Худжанд; Uzbek: Хўжанд, romanized: Хo'jand; Persian: خجند, romanized: Khojand), sometimes spelled Khodjent and known as Leninabad (Russian: Ленинабад, romanized: Leninabad; Tajik: Ленинобод, romanized: Leninobod; Persian: لنینآباد, romanized: Leninâbâd) from 1936 to 1991, is the second-largest city of Tajikistan and the capital of Tajikistan's northernmost Sughd province.

Khujand is one of the oldest cities in Central Asia, dating back about 2,500 years to the Persian Empire. Situated on the Syr Darya river at the mouth of the Fergana Valley, Khujand was a major city along the ancient Silk Road. After being captured by Alexander the Great in 329 BC, it was renamed Alexandria Eschate and has since been part of various empires in history, including the Umayyad Caliphate (8th century), the Mongol Empire (13th century) and the Russian empire (19th century).[3] Today, the majority of its population are ethnic Tajiks and the city is close to the present borders of both Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan.

History

Antiquity

Khujand may have been the site of Cyropolis (Κυρούπολις) which was established when king Cyrus the Great founded the city during his last expedition against the Saka tribe of Massagetae shortly before his death. Alexander the Great later built his furthest Greek settlement near Cyropolis in 329 BC and named it Alexandria Eschate (Greek: Ἀλεξάνδρεια Ἐσχάτη) or "Alexandria The Furthest".[4] The city would form a bastion for the Greek settlers against the nomadic Scythian tribes who lived north of the Syr Darya River. According to the Roman writer Curtius, Alexandria Ultima (Alexandria the Furthest) retained its Hellenistic culture as late as 30 BC. The city became a major staging point on the northern Silk Road.[5] It also became a cultural hub and several famous poets and scientists came from this city.

The Sheik Muslihiddin Mausoleum and Jami Masjidi Yami mosque, together with the fortress of Khujand, which was built over 2,500 years ago together and underwent several stages of complete destruction and renovation, were preserved by Khujand, as were some monuments from the 16th-17th century.[6]

Post-classical

In the early eighth century AD, Khujand was captured by the forces of the Umayyad Caliphate, under Qutayba ibn Muslim. The city was incorporated into the Umayyad and subsequent Abbasid Caliphates, and a process of Islamicization began. In the late ninth century, however, it reverted to local rule and was incorporated into the Samanid Empire. It came under the rule of the Kara-Khanid Khanate in 999 and after the division of Kara Khanids in 1042, it was initially part of Eastern Kara Khanids, and then later passed to the western one. Molana Wajeeh-ud-Din Khujandi was a Muslim scholar of Khujand who migrated to Dilli. Hafiz Khawaja Sheikh Mehmood (Moena Doz) was his nephew. His daughter Bibi Qursam Khatoon was mother Of Baba Fareed ud Din Ganj e Shakr.

Karakhitans conquered it in 1137, but it passed to Khwarazmshahs in 1211. In 1220, it strongly resisted the Mongol hordes and was thus laid to waste. In the 14th century, the city was part of the Chagatai Khanate until it was incorporated into the Timurid dynasty' in the late 14th century, under which it flourished greatly. The Shaybanid dynasty of Bukhara next annexed Khojand, until it was taken over by the Kokand Khanate in 1802, however, Bukhara regained it in 1842 until it was lost a few decades later to Russia.

Russian Empire

In 1866, as most of Central Asia was occupied by Russian Empire, the city became part of the General Governorate of Turkestan, under Tsarist Russia. The threat of forced conscription during World War I led to protests in the city in July 1916, which turned violent when demonstrators attacked Russian soldiers.[7]

Soviet Union

During the initial period of Soviet power in Central Asia, Khujand was part of the Turkestan ASSR that was created in 1918. When the latter was dismantled in 1924 on the principle of national delimitation, the city became a part of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic. In 1929, the previously created Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (contained within the Uzbek SSR) was upgraded to union-level republic as the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic, and in order to gain a sufficient number of inhabitants (preferably from the titular ethnic group) the city of Khujand and the surrounding area, inhabited mainly by ethnic Tajiks, was transferred by Soviets from the Uzbek SSR to the Tajik SSR.

The city was renamed Leninobad on 10 January 1936[8] and it remained part of the Soviet Union until 1991.

Now a part of the Tajik SSR, Leninobad became the second-largest city in the republic, though the city's location within the historically more urban, prosperous, and commercially central Fergana Valley and a long history of being a densely populated urban centre meant that Khujand and its region were sometimes viewed as more developed and cosmopolitan than the newly designated capital and boom-town of Dushanbe/Stalinabad (the latter was a small town of 6,000 when the Tajik SSR was created in 1926 and had reached over 200,000 inhabitants ten years later).[9]

Post-Soviet period and independence

It reverted to its original name in 1992 after the breakup of the Soviet Union and the independence of Tajikistan, and the city continued to be the second-largest city in the nation.

In 1996 the city experienced the Ashurov protests during which citizens called for the President, Emomali Rakhmonov to step down. The popular protests were followed by a protest from the city's prisoners, many of whom had been sentenced to long jail terms for minor crimes and who were living in poor conditions. The protest led to the Khujand prison riot in which between 24 and 150 prisoners were killed.

In the early 2000s many residents of Khujand had little to no access to water, and what water they did have was unsafe to drink and had to be boiled. In 2004, The Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs and the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development joined to help improve the situation, providing 32,000 water meters for inhabitants and developing improved access to water. Residents pay for their water supply, which in turn helps Khujand's municipal water company to continue to renovate and improve their services. The project is in its third stage of development and was to be completed by 2017. In comparison to other Central Asian projects aiming to improve access to water, this project is considered a success and has been applied to Kyrgyz cities and towns such as Osh, Jalal-Abad, Karabalta, and Talas, with a possible extension into the Kyrgyz capital of Bishkek.[10]

On 3 September 2010, a suicide attack was committed in the city by the al-Qaeda linked Jamaat Ansarullah militant group, resulting in the deaths of 4 people.[11][12]

In April 2017, Pastor Bakhrom Kholmatov was detained after a raid on Sunmin Sunbogym Protestant Church in Khujand. Kholmatov was accused of singing too loudly and "interfering with the comfort and rest" of people who lived nearby, and jailed for three years.[13]

Transportation

_AN2218848.jpg.webp)

Khujand Airport has regularly scheduled flights to Dushanbe as well as several cities in Russia. There is also a rail connection between Khujand and Samarkand in Uzbekistan on the way to Dushanbe.[14][15] The city is connected by road to Panjakent in the Zeravshan River Valley as well as Dushanbe via the Anzob Tunnel.

The 5-km tunnel, located 80 km northwest of Dushanbe and built with assistance from Iran, is also a transit route between Dushanbe and the Uzbek capital of Tashkent. Previously, particularly during cold seasons, the lack of a direct link between northern and southern Tajikistan often led to disruptions of commercial activities in the region [16]

Education

The city is home to Khujand State University, Tajikistan State University of Law, Business, & Politics, Polytechnical Institute of Technical University of Tajikistan, and Khujand Medical College as well as 2-year technical colleges. Secondary education is funded by the state except when administered at private institutions. Higher education in universities and colleges is subsidized by the Tajik Ministry of Education.

Demographics

Khujand is mainly inhabited by ethnic Tajiks. Results of population census carried out in 2010: Tajiks – 84%, Uzbeks – 14%, Russians – 0.4%, and others – 1.6%. Sunni Islam is a mainly practiced religion in the city.[8] The population of the city is 181,600 (Report of Statistical Agency 2019).[8] The population in Khujand agglomeration is 931,900 people (2019).

Cultural sites

The city is home to the Historical Museum of Sughd located within the Khujand Fortress and having around 1200 exhibitions with most being open to the public.[17] The Sheikh Muslihiddin mausoleum is located on the main square across the Panjshanbe Market (Бозори Панҷшанбе / Persian for "Thursday's Market"), one of the largest covered markets in Central Asia.[18]

Climate

Khujand experiences a temperate semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with cold, snowy winters and hot, dry summers. Precipitation is light, and it generally falls in winter and autumn.

| Climate data for Khujand (1991–2020, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

39.9 (103.8) |

43.5 (110.3) |

45.9 (114.6) |

43.8 (110.8) |

39.8 (103.6) |

33.8 (92.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

45.9 (114.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

28.6 (83.5) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.7 (96.3) |

34.1 (93.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

3.3 (37.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.5 (41.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

21.9 (71.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

10.1 (50.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.8 (−9.0) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

0.8 (33.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−22.8 (−9.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 14 (0.6) |

20 (0.8) |

37 (1.5) |

42 (1.7) |

48 (1.9) |

10 (0.4) |

2 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

15 (0.6) |

20 (0.8) |

16 (0.6) |

228 (9.2) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.4 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 12.6 | 12.0 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 7.4 | 10.4 | 100.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.8 | 75.4 | 64.0 | 56.3 | 48.7 | 34.8 | 33.8 | 38.4 | 43.3 | 55.4 | 75.2 | 76.4 | 56.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 126 | 131 | 168 | 211 | 297 | 358 | 382 | 363 | 300 | 225 | 160 | 106 | 2,827 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net,[19] NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[20] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: climatebase.ru (precipitation days, humidity),[21] | |||||||||||||

Sister cities

Notable residents

- Munzifa Gafarova (1924–2013), Tajikistani philosopher

- Ashura Nosirova (1924–2011), Tajikistani dancer

- Bakhtiyor Odinaev, Tajikistani stage manager, costume designer and artist

- Manzura Uldjabaeva (born 1952), Tajikistani artist

- Henri Weber (1944–2020), French politician

See also

References

- ↑ "Population size, Republic of Tajikistan on January 1, 2019" (PDF) (in Tajik). Tajikistan Statistics Agency. 2019. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ↑ "КОНСТИТУЦИЯ РЕСПУБЛИКИ ТАДЖИКИСТАН". prokuratura.tj. Parliament of Tajikistan. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ↑ Abdullaev, Kamoludin (2018). "Khujand". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7.

- ↑ Prevas, John. (2004). Envy of the Gods: Alexander the Great's Ill-Fated Journey across Asia, p. 121. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ISBN 0-306-81268-1.

- ↑ "Khujand: a travel guide". Caravanistan. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ↑ "Khujand". Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ↑ A Country Study: Tajikistan, Tajikistan under Russian Rule, Library of Congress Call Number DK851 .K34 1997

- 1 2 3 About Khujand, http://fezsughd.tj/en/about_khujand/ Archived 2014-12-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Kalinovsky, Artemy M. (15 May 2018). Laboratory of socialist development: Cold War politics and decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan. Ithaca. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-5017-1558-7. OCLC 1013988565.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ International Crisis Group. "Water Pressures in Central Asia", CrisisGroup.org. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Pannier, Bruce (13 May 2022). "Northern Afghanistan and the New Threat to Central Asia". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

Jamaat Ansarullah, for instance, is a terrorist group from Tajikistan that claimed responsibility for a suicide bomber attack in the northern Tajik city of Khujand in September 2010 that killed four people.[7] The Tajik government launched a crackdown on suspected Jamaat Ansarullah members and since then the group has been operating alongside the Taliban in northern Afghanistan.

- ↑ Zenn, Jacob; Kuehnast, Kathleen (October 2014). "Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan" (PDF). United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

Jamaat Ansarullah first carried out an attack in 2010, when it claimed responsibility for an al-Qaeda-trained member's suicide bombing at a police station in Khujand, a city in Tajikistan's northern province of Sughd in the Fergana Valley.

- ↑ "Prisoner Alert - Bakhrom Kholmatov". www.prisoneralert.com.

- ↑ http://www.caravanistan.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/central-asia-railroad-train-map-kazakhstan-uzbekistan-kyrgyzstan-tajikistan-turkmenistan-afghanistan.gif

- ↑ "Train in Tajikistan". Caravanistan. 28 February 2023.

- ↑ "Tajikistan to complete construction of major tunnel in 2015 | Shanghai Daily". archive.shine.cn. Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- ↑ "Khujand fortress". www.advantour.com.

- ↑ "Azianatravel.com". www.azianatravel.com. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ КЛИМАТ УЛАН-БАТОРА (in Russian). Pogoda.ru.net. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Leninbad (Khujand) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ↑ "Leninabad, Tajikistan". Climatebase.ru. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

Sources

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265. Draft annotated English translation. Weilue: The Peoples of the West (See under the heading for "Northern Wuyi").

External links

- Official website (in Russian)