| Khepri | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Khepri is often represented as a scarab holding aloft the morning sun, or a scarab-headed man. In one hand, the sun god holds a was scepter and in the other an ankh.[1] | |||||

| Name in hieroglyphs | |||||

| Major cult center | Heliopolis[2] | ||||

| Symbol | scarab, blue lotus | ||||

| Parents | Nut (some accounts) | ||||

| Offspring | All gods (some accounts), Ma’at | ||||

Khepri (Egyptian: ḫprj, also transliterated Khepera, Kheper, Khepra, Chepri) is a scarab-faced god in ancient Egyptian religion who represents the rising or morning sun. By extension, he can also represent creation and the renewal of life.[2]

Symbolism

.svg.png.webp)

Khepri (ḫprj) is derived from the Egyptian language verb ḫpr, meaning to "develop", "come into being", or "create".[3] The god was connected to and often depicted as a scarab beetle (ḫprr in Egyptian). Young dung beetles, having been laid as eggs within the dung ball, emerge from it fully formed and thus were considered to have been created from nothingness.[4] Egyptians believed that each day the sun was also reborn or created from nothing.[4] In the same way that the beetle pushes large balls of dung along the ground, Khepri moved the newly-born sun across the sky.[4] Khepri was a solar deity and thus connected to the rising sun and the mythical creation of the world.[5] The god and the scarab beetle represent creation and rebirth.[5][6]

Religion

There was no cult devoted to Khepri, and he was largely subordinate to the greater sun god Ra. The sun god was however included in the creationist theory of Heliopolis and later Thebes.[2] Often, Khepri and another solar deity, Atum, were seen as aspects of Ra: Khepri was the morning sun, Ra was the midday sun, and Atum was the sun in the evening.[3] As a deity, Khepri's four main functions were creator, protector, sun-god, and the god of resurrection.[2] The central belief surrounding Khepri was the god's ability to renew life, in the same way he restored the sun's existence every morning.[2] Mummified scarab beetles and scarab amulets have been found in Pre-dynastic graves, indicating that Khepri was respected early on in the history of Ancient Egypt.[2]

Appearance

Khepri was principally depicted as a Scarabaeus sacer scarab beetle, though in some tomb paintings and funerary papyri he is represented as a human male with a scarab as a head, or as a scarab with a male human head emerging from the beetle's shell. He is also depicted as a scarab in a solar barque held aloft by Nun. The scarab amulets that the Egyptians used as jewelry and as seals allude to Khepri and the newborn sun.[7] The beetle carvings became so common that excavators find them throughout the Mediterranean.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

Etymology

The name "Khepri" appears most often in the Pyramid texts and usually has the scarab hieroglyph as a determinative or ideogram.[5] Khepri (ḫprj) can also be spelled "Kheper", which is the Egyptian term used to denote the sun god, the scarab beetle, and the verb "to come into existence".[4]

Kheper could also stand for "to change", "to happen" etc.

Origin

It is thought that Khepri came into existence in the same manner as a young scarab beetle emerges from its dung ball fully formed.[4]

Ancient Egyptians used to think that beetles expressed the sun's motion by rolling their feces on the sand, which is why the sun god Khepri is associated with this particular species of beetle.

Khepri was considered below the sun god Ra in rank, so no shrine was built for him. Another sun-god Atum and Khepri are often considered to be part of Ra. As stated in The Book of the Dead,[5] Khepri was also sometimes believed to be a part of Atum.[8]

Gallery

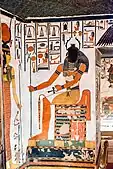

Painting of Khepri in (QV66) the entrance to the tomb of Nefertari.

Painting of Khepri in (QV66) the entrance to the tomb of Nefertari. Nun, god of the waters of chaos, lifts the barque of the sun god Ra (represented by both the scarab and the sun disk) into the sky at the beginning of time.

Nun, god of the waters of chaos, lifts the barque of the sun god Ra (represented by both the scarab and the sun disk) into the sky at the beginning of time. Painting of Khepri holding the sun.

Painting of Khepri holding the sun. Relief of Khepri holding the sun.

Relief of Khepri holding the sun..png.webp) Khepri on the boat guiding the deceased.

Khepri on the boat guiding the deceased.![On this relief panel, Khepri is depicted solely as a scarab beetle. Above his head the sun god holds the Duat, a symbol for the afterlife. The scarab stands on a sun disk with sun rays extending downwards.[8]](../I/Relief_panel_showing_two_baboons_offering_the_wedjat_eye_to_the_sun_god_Khepri%252C_who_holds_the_Underworld_sign_MET_DP241031.jpg.webp) On this relief panel, Khepri is depicted solely as a scarab beetle. Above his head the sun god holds the Duat, a symbol for the afterlife. The scarab stands on a sun disk with sun rays extending downwards.[9]

On this relief panel, Khepri is depicted solely as a scarab beetle. Above his head the sun god holds the Duat, a symbol for the afterlife. The scarab stands on a sun disk with sun rays extending downwards.[9]![Scarab beetles were one of the most common material objects made by the ancient Egyptians. These scarabs, from the Middle Kingdom, were likely used as jewelry, specifically amulets. The scarab beetle is symbolic of Khepri, the Egyptian sun deity who represents creation and rebirth[9].](../I/Ancient_Egyptian_Scarabs.jpg.webp) Scarab beetles were one of the most common material objects made by the ancient Egyptians. These scarabs, from the Middle Kingdom, were likely used as jewelry, specifically amulets. The scarab beetle is symbolic of Khepri, the Egyptian sun deity who represents creation and rebirth.[10]

Scarab beetles were one of the most common material objects made by the ancient Egyptians. These scarabs, from the Middle Kingdom, were likely used as jewelry, specifically amulets. The scarab beetle is symbolic of Khepri, the Egyptian sun deity who represents creation and rebirth.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Studies in Aegean Art and Culture: A New York Aegean Bronze Age Colloquium in Memory of Ellen N. Davis. INSTAP Academic Press. 2016. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1kk66gk. ISBN 978-1-931534-86-4. JSTOR j.ctt1kk66gk.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 van Ryneveld, Maria M. The Presence and Significance of Khepri in Egyptian Religion and Art, University of Pretoria (South Africa), Ann Arbor, 1992. ProQuest 304016142.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. pp. 230–233

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Liszka, Kate. “Scarab Amulets in the Egyptian Collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, vol. 74, 2015, pp. 4–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26388759. Accessed 1 Dec. 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Popielska-Grzybowska, Joanna. "The concept of ḫprr in Old Kingdom religious texts". Old Kingdom, New Perspectives. online: Oxbow Books. pp. 230–234.

- ↑ Studies in Aegean Art and Culture: A New York Aegean Bronze Age Colloquium in Memory of Ellen N. Davis. INSTAP Academic Press. 2016. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1kk66gk. ISBN 978-1-931534-86-4. JSTOR j.ctt1kk66gk.

- ↑ Hart, George (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Routledge. pp. 84–85

- ↑ Zaman, S. (2018). Mishor (Egypt). Kolkata, India: Aranyaman. p. 55.

- ↑ "Relief panel showing two baboons offering the wedjat eye to the sun god Khepri, who holds the Underworld sign". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Liszka, Kate. “Scarab Amulets in the Egyptian Collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.” Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, vol. 74, 2015, pp. 4–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26388759. Accessed 1 Dec. 2020.

External links

![]() Media related to Khepri at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Khepri at Wikimedia Commons