| Ismail Pasha Ismā‘īl Bāshā إسماعيل باشا | |

|---|---|

| |

| Khedive of Egypt and Sudan | |

| Reign | 19 January 1863 – 26 June 1879 |

| Predecessor | Sa'id I (as Wāli (unrecognized Khedive) of Egypt) |

| Successor | Tewfik I |

| Born | 12 January 1830 Cairo, Egypt Eyalet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 2 March 1895 (aged 65) Istanbul, Ottoman Empire |

| Burial | |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | Tewfik I of Egypt Hussein Kamel I of Egypt Fuad I of Egypt Prince Ibrahim Ilhami Pasha Prince Ali Jamal Pasha Prince Hassan Ismail Pasha Prince Mahmud Hamdi Pasha Prince Reshid Ismail Bey Princess Tawhida Hanim Princess Fatima Hanim Princess Zainab Hanim Princess Jamila Fadila Hanim Princess Amina Hanim Princess Nimetullah Hanim Princess Amina Aziza Hanim |

| House | Alawiyya |

| Father | Ibrahim I |

| Mother | Hoshiyar Qadin |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Isma'il Pasha (Egyptian Arabic: إسماعيل باشا Ismā‘īl Bāshā; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), also known as 'Ismail the Magnificent, was the Khedive of Egypt and ruler of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain and France. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his grandfather, Muhammad Ali Pasha, he greatly modernized Egypt and Sudan during his reign, investing heavily in industrial and economic development, urbanization, and the expansion of the country's boundaries in Africa.

His philosophy can be glimpsed in a statement that he made in 1879: "My country is not longer only in Africa; we are now part of Europe, too. It is therefore natural for us to abandon our former ways and to adopt a new system adapted to our social conditions".

In 1867 he also secured Ottoman and international recognition for his title of Khedive (Viceroy) in preference to Wāli (Governor) which was previously used by his predecessors in the Eyalet of Egypt and Sudan (1517–1867). However, Isma'il's policies placed the Khedivate of Egypt and Sudan (1867–1914) in severe debt, leading to the sale of the country's shares in the Suez Canal Company to the British government, and his ultimate toppling from power in 1879 under British and French pressure.

The city of Ismailia is named in his honor.

Family

The second of the three sons of Ibrahim Pasha, and the grandson of Muhammad Ali, Isma'il, of Albanian descent, was born in Cairo at Al Musafir Khana Palace.[5] His mother was Circassian Hoshiyar Qadin,[6] third wife of his father.[7] Hoshiyar Qadin (also known as Khushiyar Qadin) is reported to be the sister of Pertevniyal Sultan, mother of the Ottoman Emperor Abdulaziz, who ruled from 1861 to 1876 and who also was deposed at the behest of the western powers. Thus, Isma'il Pasha was ruling Egypt and Sudan for the entire period when his cousin, Abdulaziz, was ruling the Ottoman empire.

Youth and education

After receiving a European education in Paris where he attended the École d'état-major, he returned home, and on the death of his elder brother became heir to his uncle, Sa'id, the Wāli and Khedive of Egypt and Sudan. Sa'id, who apparently conceived his safety to lie in ridding himself as much as possible of the presence of his nephew, employed him in the next few years on missions abroad, notably to the Pope, the Emperor Napoleon III, and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. In 1861 he was dispatched at the head of an army of 18,000 to quell an insurrection in Sudan, a mission which he accomplished.[8]

Khedive of Egypt

After the death of Sa'id, Isma'il was proclaimed Khedive on 19 January 1863, though the Ottoman Empire and the other Great Powers recognized him only as Wāli. Like all Egyptian and Sudanese rulers since his grandfather Muhammad Ali Pasha, he claimed the higher title of Khedive, which the Sublime Porte had consistently refused to sanction. Finally, in 1867, Isma'il succeeded in persuading the Ottoman Sultan Abdülaziz to grant a firman finally recognizing him as Khedive in exchange for an increase in the tribute, because of the Khedive's help in the Cretan Revolt between 1866 and 1869. Another firman changed the law of succession to direct descent from father to son rather than brother to brother, and a further decree in 1873 confirmed the virtual independence of the Khedivate of Egypt from the Porte.

Reforms

Isma'il spent heavily—some went to bribes to Constantinople to facilitate his reform projects. Much of the money went for the construction of the Suez Canal. About £46 million went to construct 8,000 miles (13,000 km) of irrigation canals to help modernize agriculture. He built over 900 miles (1,400 km) railroads, 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of telegraph lines, 400 bridges, harbor works in Alexandria, and 4,500 schools. The national debt rose from £3 million to about £90 million, in a country with 5 million population and an annual treasury revenue of about £8 million.[9]

Isma'il launched vast schemes of internal reform on the scale of his grandfather, remodeling the customs system and the post office, stimulating commercial progress, creating a sugar industry, building the cotton industry, building palaces, entertaining lavishly, and maintaining an opera and a theatre.[8] Over one hundred thousand Europeans came to work in Cairo, where he facilitated building an entire new quarter of the city on its western edge modeled on Paris. Alexandria was also improved. He launched a vast railroad building project that saw Egypt and Sudan rise from having virtually none to the most railways per habitable kilometer of any nation in the world.

Education reform increased the education budget more than tenfold. Traditional primary and secondary schools were expanded and specialized technical and vocational schools were created. Students were once again sent to Europe to study on educational missions, encouraging the formation of a Western-trained elite. A national library was founded in 1871.[10]

One of his most significant achievements was to establish an assembly of delegates in November 1866. Though this was supposed to be a purely advisory body, its members eventually came to have an important influence on governmental affairs. Village headmen dominated the assembly and came to exert increasing political and economic influence over the countryside and the central government. This was shown in 1876 when the assembly persuaded Isma'il to reinstate the law (enacted by him in 1871 to raise money and later repealed) that allowed landownership and tax privileges to persons paying six years' land tax in advance.

Isma'il tried to reduce slave trading and with the advice and financial backing of Yacoub Cattaui extended Egypt's rule in Africa. In 1874 he annexed Darfur, but was prevented from expanding into Ethiopia after his army was repeatedly defeated by Emperor Yohannes IV, first at Gundet on 16 November 1875, and again at Gura in March of the following year.

War with Ethiopia

Isma'il dreamt of expanding his realm across the entire Nile including its diverse sources, and over the whole African coast of the Red Sea.[11] This, together with rumours about rich raw material and fertile soil, led Isma'il to expansive policies directed against Ethiopia under the Emperor Yohannes IV. In 1865 the Ottoman Sublime Porte ceded the African portion of the Habesh Eyalet (with Massawa and Suakin at the Red Sea as the main cities of that province) to Isma'il. This province, which neighboured Ethiopia, first consisted of a coastal strip only but expanded subsequently inland into territory controlled by the Ethiopian ruler. Here Isma'il occupied regions originally claimed by the Ottomans when they had established the province (eyalet) of Habesh in the 16th century. New economically promising projects, like huge cotton plantations in the Barka delta, were started. In 1872 Bogos (with the city of Keren) was annexed by the governor of the new "Province of Eastern Sudan and the Red Sea Coast", Werner Munzinger Pasha. In October 1875 Isma'il's army try to occupied the adjacent highlands of Hamasien, which were then tributary to the Ethiopian Emperor, and suffered defeat at the Battle of Gundet. In March 1876 Isma'il's army tried again and suffered a second dramatic defeat by Yohannes's army at Gura. Isma'il's son Hassan was captured by the Ethiopians and only released after a large ransom. This was followed by a long cold war, only finishing in 1884 with the Anglo-Egyptian-Ethiopian Hewett Treaty, when Bogos was given back to Ethiopia. The Red Sea Province created by Ismail and his governor Munzinger Pasha was taken over by the Italians shortly thereafter and became the territorial basis for the Colony of Eritrea (proclaimed in 1890).

Khedive's Somali Coast

The jurisdiction of Isma'il Pasha from the 1870s until 1884 included the entire northern coast of Somalia, up to the eastern coast at Ras Hafun in contemporary Puntland.[12] The Khedive's northern Somali Coast territory was reached as far inland as Harar, although it was subsequently ceded to Britain in 1884 due to internal difficulties of Egypt.[13]

Suez Canal

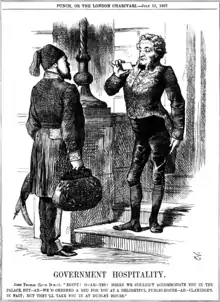

Isma'il's khedivate is closely connected to the building of the Suez Canal. He agreed to, and oversaw, the Egyptian portion of its construction. On his accession, at the behest of Yacoub Cattaui his minister of Finance and close advisor, he refused to ratify the concessions to the Canal company made by Sa'id, and the question was referred in 1864 to the arbitration of Napoleon III, who awarded £3,800,000 to the company as compensation for the losses they would incur by the changes which Isma'il insisted upon in the original grant. Isma'il then used every available means, by his own undoubted powers of fascination and by judicious expenditure, to bring his personality before the foreign sovereigns and public, and he had much success.[8] In 1867 he visited Paris during the Exposition Universelle (1867) with Sultan Abdülaziz, and also London, where he was received by Queen Victoria and welcomed by the Lord Mayor. While in Britain he also saw a British Royal Navy Fleet Review with the Sultan. In 1869 he again paid a visit to Britain. When the Canal finally opened, Isma'il held a festival of unprecedented scope, most of it financed by the Cattaui banking house, from whom he borrowed $1,000,000, inviting dignitaries from around the world.

Debts

These developments – especially the costly war with Ethiopia – left Egypt in deep debt to the European powers, and they used this position to wring concessions out of Isma'il. One of the most unpopular among Egyptians and Sudanese was the new system of mixed courts, by which Europeans were tried by judges from their own states, rather than by Egyptian and Sudanese courts. But at length the inevitable financial crisis came. A national debt of over £100 million sterling (as opposed to three millions when he acceded to the throne) had been incurred by the Khedive, whose fundamental idea of liquidating his borrowings was to borrow at increased interest. The bond-holders became restive, chief among them the House of Cattaui. Judgments were given against the Khedive in the international tribunals. When he could raise no more loans, he sold the Egyptian and Sudanese shares in the Suez Canal Company in 1875 with the assistance of Yacoub Cattaui to the British government for £3,976,582; this was immediately followed by the beginning of direct intervention by the Great Powers in Egypt and Sudan.[8]

In December 1875, Stephen Cave and John Stokes were sent out by the British government to inquire into the finances of Egypt,[15] and in April 1876 their report was published, advising that in view of the waste and extravagance it was necessary for foreign Powers to interfere in order to restore credit. The result was the establishment of the Caisse de la Dette. A subsequent investigation in October by George Goschen and Joubert resulted in the establishment of joint Anglo-French control over most of the Egyptian government's finances. A further commission of inquiry by Major Evelyn Baring (afterwards 1st Earl of Cromer) and others in 1878 culminated in Isma'il handing over much of his personal estates' to the nation and accepting the position of a constitutional sovereign, with Nubar as premier, Charles Rivers Wilson as finance minister, and de Blignières as minister of public works.[8]

As the historian Eugene Rogan has observed, "the irony of the situation was that Egypt had embarked on its development schemes to secure independence from Ottoman and European domination. Yet with each new concession, the government of Egypt made itself more vulnerable to European encroachment."[16]

Urabi Revolt and exile

This control of the country by Europeans was unacceptable to many Egyptians, who united behind a disaffected Colonel Ahmed Urabi. The Urabi Revolt consumed Egypt. Hoping the revolt could relieve him of European control, Isma'il did little to oppose Urabi and gave into his demands to dissolve the government. Britain and France took the matter seriously, and insisted in May 1879 on the reinstatement of the British and French ministers. With the country largely in the hands of Urabi, Isma'il could not agree, and had little interest in doing so. As a result, the British, and French governments pressured the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II to depose Isma'il Pasha, and this was done on 26 June 1879. The more pliable Tewfik Pasha, Ismail's eldest son, was made his successor. Isma'il Pasha left Egypt and initially went into exile to Resina, today Ercolano near Naples, until 1885 when he was eventually permitted by Sultan Abdülhamid II to retire to his palace in Emirgan[17] on the Bosporus in Constantinople. There he remained, more or less a state prisoner, until his death.[8] According to TIME magazine, he died while trying to guzzle two bottles of champagne in one draft.[18] He was later buried in Cairo.

Language

Although he ruled Egypt, where the common language was Arabic, Isma'il spoke Turkish best and could not speak Arabic. Nevertheless, under his reign, the use of Arabic in government gradually increased at the expense of Turkish, which had been the language of the ruling elite in the Nile delta during the hundreds of years of Ottoman rule. In the following decades, Arabic would further expand and eventually replace Turkish in the army and in administration, leaving Turkish to be used only in correspondence with the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople.[19][20]

Honours

.svg.png.webp) Order of Glory, Nichan Iftikhar

Order of Glory, Nichan Iftikhar.svg.png.webp) Grand Cordon (civil) of the Order of Leopold, 10 February 1863[21]

Grand Cordon (civil) of the Order of Leopold, 10 February 1863[21].svg.png.webp) Order of Nobility, Special Class, 1863

Order of Nobility, Special Class, 1863.svg.png.webp) Order of Osmanieh, Special class, 1863

Order of Osmanieh, Special class, 1863 Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Leopold, 1864[22]

Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Leopold, 1864[22].svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle, 1865[23]

Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of the Mexican Eagle, 1865[23].svg.png.webp) Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, 27 July 1866[24]

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword, 27 July 1866[24] Honorary Grand Cross (civil) of the Order of the Bath, 18 December 1866[25]

Honorary Grand Cross (civil) of the Order of the Bath, 18 December 1866[25] Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion, 1866

Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion, 1866_crowned.svg.png.webp) Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 29 January 1867[26]

Knight of the Supreme Order of the Most Holy Annunciation, 29 January 1867[26].svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur, 1867

Grand Cross of the Legion d'Honneur, 1867 Honorary Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India, 27 August 1868[27]

Honorary Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India, 27 August 1868[27].svg.png.webp) Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 30 December 1868[28]

Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 30 December 1868[28].svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 3 April 1865[28]

Grand Cross of the Order of the Red Eagle, 3 April 1865[28] Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog, 3 November 1869[29]

Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog, 3 November 1869[29]_crowned.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1869

Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1869_crowned.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy, 1869

Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown of Italy, 1869.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, 1869

Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer, 1869.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1869[30]

Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1869[30].svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1872[31]

Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1872[31].svg.png.webp) Honorary member: Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1874

Honorary member: Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1874 Grand Cross of the House and Merit Order of Peter Frederick Louis, with Golden Crown, 5 February 1875[32]

Grand Cross of the House and Merit Order of Peter Frederick Louis, with Golden Crown, 5 February 1875[32].svg.png.webp) Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar, 1st Class, 1875

Order of the Brilliant Star of Zanzibar, 1st Class, 1875 Order of the Brilliant Star of Egypt, 1st Class, 1875

Order of the Brilliant Star of Egypt, 1st Class, 1875

Further reading

- Dye, William McEntyre. Moslem Egypt and Christian Abyssinia; Or, Military Service Under the Khedive, in his Provinces and Beyond their Borders, as Experienced by the American Staff. New York: Atkin & Prout (1880).

- Helen Chapin Metz. Egypt: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1990., Helen Chapin Metz, ed.

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hassan, H.; Fernea, E.; Fernea, R. (2000). In the House of Muhammad Ali: A Family Album, 1805-1952. American University in Cairo Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-61797-241-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Doumani, B. (2003). Family History in the Middle East: Household, Property, and Gender. Family History in the Middle East: Household, Property, and Gender. State University of New York Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7914-5679-8.

- 1 2 3 Öztürk, D. (2020). "Remembering" Egypt's Ottoman Past: Ottoman Consciousness in Egypt, 1841-1914. Ohio State University. p. 129.

- ↑ Tugay, E.F. (1963). Three Centuries: Family Chronicles of Turkey and Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 144.

- ↑ "Travel - Yahoo Style". Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ "His Highness Kavalali Ibrahim Pasa". Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ "UQconnect, The University of Queensland". Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Ismail". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 875.

- ↑ William L. Langer, European alliances and alignments, 1871-1890 (1950) p 355.

- ↑ Cleveland, William L.; Burton, Martin (2013). A history of the modern Middle East (Fifth ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780813348339.

- ↑ "Moslem Egypt and Christian Abyssinia; Or, Military Service Under the Khedive, in his Provinces and Beyond their Borders, as Experienced by the American Staff". World Digital Library. 1880. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ The Scramble in the Horn of Africa; History of Somalia (1827-1977), M. O. Omar, p. 57 "by a Convention signed at Alexandria on 7th of September 1877, by which Her Majesty's Government recognised the Khedive's jurisdiction under the suzerainty of the Porte over the Somali Coast as far as Ras Hafun"

- ↑ The Scramble in the Horn of Africa; History of Somalia (1827-1977), M. O. Omar, p. 57 "made over its possessions on the Somali coast to the Khedive, Ismail Pasha, who had in the previous year established himself at Harrar in the interior. In 1884, owing to internal difficulties, the Egyptian Government found it necessary to withdraw their garrisons from this region, and the Porte not being at the time prepared to make any effective assertion of its authority, Zaila came into British occupation"

- ↑ McSweeney, Anna (March 2015). "Versions and Visions of the Alhambra in the Nineteenth-Century Ottoman World". West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture. 22 (1): 44–69. doi:10.1086/683080. ISSN 2153-5531. S2CID 194180597.

- ↑ "Welcome Fortune City Customers | Dotster". Members.fortunecity.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ↑ Rogan, Eugene (2011). The Arabs. Penguin. p. 101.

- ↑ Historic photo of the Khedive Ismail Pasha Palace (Hıdiv İsmail Paşa Sarayı) that once stood in the Sarıyer district of Constantinople, on the shores of the Bosporus.

- ↑ Morrow, Lance (31 March 1986). "Essay: The Shoes of Imelda Marcos". Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2016 – via www.time.com.

- ↑ Robert O. Collins, A History of Modern Sudan, Cambridge University Press, 2008 p.10

- ↑ P. M. Holt, M. W. Daly, A History of the Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day, Routledge 2014 p.36

- ↑ "Liste des Membres de l'Ordre de Léopold", Almanach Royal Officiel (in French), 1864, p. 53 – via Archives de Bruxelles

- ↑ "Ritter-Orden: Oesterreichsch-kaiserlicher Leopold-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1883, p. 128, retrieved 5 February 2021

- ↑ "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), Mexico City: Imp. de J.M. Lara, 1866, p. 243

- ↑ Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1877, p. 372, retrieved 6 January 2018 – via runeberg.org

- ↑ Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 210

- ↑ Italia : Ministero dell'interno (1891). Calendario generale del Regno d'Italia. Unione tipografico-editrice. p. 54.

- ↑ Shaw, p. 309

- 1 2 "Königlich Preussische Ordensliste", Preussische Ordens-Liste (in German), Berlin, 1: 6, 22, 1886

- ↑ Bille-Hansen, A. C.; Holck, Harald, eds. (1889) [1st pub.:1801]. Statshaandbog for Kongeriget Danmark for Aaret 1889 [State Manual of the Kingdom of Denmark for the Year 1889] (PDF). Kongelig Dansk Hof- og Statskalender (in Danish). Copenhagen: J.H. Schultz A.-S. Universitetsbogtrykkeri. pp. 7–8. Retrieved 7 February 2021 – via da:DIS Danmark.

- ↑ "Ritter-Orden: Königlich-ungarischer St. Stephan-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1883, p. 118, retrieved 5 February 2021

- ↑ Staatshandbücher für das Herzogtum Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (1890), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 45

- ↑ Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Oldenburg: 1879. Schulze. 1879. p. 34.

.svg.png.webp)