Heraklion

Ηράκλειο | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Panoramic view of the city of Heraklion and the Sea of Crete, Agios Minas Cathedral, Night view of the Harbor of Heraklion, and Venetian fortress of Koules/Castello. | |

Seal | |

Heraklion Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 35°20′25″N 25°8′4″E / 35.34028°N 25.13444°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Administrative region | Crete |

| Regional unit | Heraklion |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vasilis Lambrinos[1] |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 244.6 km2 (94.4 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 109.0 km2 (42.1 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 33 m (108 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2011)[2] | |

| • Urban | 211,370[3] |

| • Municipality | 173,993 |

| • Municipality density | 710/km2 (1,800/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 151,324 |

| • Municipal unit density | 1,400/km2 (3,600/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Heraklian, Heraclian |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 70x xx, 71x xx, 720 xx |

| Area code(s) | 281 |

| Vehicle registration | HK, HP, HZ |

| Website | Heraklion-city.gr |

Heraklion or Herakleion (/hɪˈrækliən/ hih-RAK-lee-ən; Greek: Ηράκλειο, Irákleio, pronounced [iˈrakli.o]),[4] sometimes Iraklion, is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a municipal population of 177,064[5] and 211,370 in its wider metropolitan area,[6] according to the 2011 census.

The ancient Minoan palace at Knossos is located 5.5 km (3.1m) southeast of the city. It is the second most visited archaeological site in Greece, after the Parthenon.

Heraklion was Europe's fastest growing tourism destination for 2017, according to Euromonitor, with an 11.2% growth in international arrivals.[7] According to the ranking, Heraklion was ranked as the 20th most visited region in Europe, as the 66th area on the planet and as the 2nd in Greece for the year 2017, with 3.2 million visitors[8] and the 19th in Europe for 2018, with 3.4 million visitors.[9]

Etymology

The Arab traders from al-Andalus (Iberia) who founded the Emirate of Crete moved the island's capital from Gortyna to a new castle they called rabḍ al-ḫandaq (Arabic: ربض الخندق, "Castle of the Moat") in the 820s.[10] This was hellenized as Χάνδαξ (Chándax) or Χάνδακας (Chándakas) and Latinized as Candia, which was taken into other European languages: in Italian and Latin as Candia, in French as Candie, in English as Candy, all of which could refer to the island of Crete as a whole as well as to the city alone; the Ottoman name was Kandiye.

After the Byzantine reconquest of Crete, the city was locally known as Megalo Kastro (Μεγάλο Κάστρο, 'Big Castle' in Greek) and its inhabitants were called Kastrinoi (Καστρινοί, "castle-dwellers").

The ancient name Herakleion (Ηράκλειον) was revived in the 19th century.[11] It derives from the ancient sunken port city of Heracleion, located near the Canopic Mouth of the Nile, and which remained submerged until its rediscovery in the 2000s.

History

Minoan era

Heraklion is close to the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which in Minoan times was the largest centre of population on Crete. Knossos had a port at the site of Heraklion (in the Poros-Katsambas[13] neighborhood) from the beginning of the Early Minoan period (3500 to 2100 BC).

.JPG.webp)

Antiquity

After the fall of the Minoans, Heraklion, as well as the rest of Crete in general, fared poorly, with very little development in the area. Only with the arrival of the Romans did some construction in the area begin, yet especially early into Byzantine times the area abounded with pirates and bandits.[14]

Emirate of Crete

The present city of Heraklion was founded in 824 by the Arabs under Abu Hafs Umar who had been expelled from Al-Andalus by Emir Al-Hakam I and had taken over the island from the Eastern Roman Empire. They built a moat around the city for protection, and named the city rabḍ al-ḫandaq (ربض الخندق, "Castle of the Moat", hellenized as Χάνδαξ, Chandax). It became the capital of the Emirate of Crete (c. 827–961). The Saracens allowed the port to be used as a safe haven for pirates who operated against Imperial (Byzantine) shipping and raided Imperial territory around the Aegean.

Byzantine era

In 960, Byzantine forces under the command of Nikephoros Phokas, later to become Emperor, landed in Crete and attacked the city. After a prolonged siege, the city fell in March 961. The Saracen inhabitants were slaughtered, the city looted and burned to the ground. Soon rebuilt, the town remained under Byzantine control for the next 243 years.

Venetian era

In 1204, the city was bought by the Republic of Venice as part of a complicated political deal which involved, among other things, the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade restoring the deposed Eastern Roman Emperor Isaac II Angelus to his throne. The Venetians improved on the ditch of the city by building enormous fortifications, most of which are still in place, including a giant wall, in places up to 40 m thick, with 7 bastions, and a fortress in the harbour. Chandax was renamed Candia and became the seat of the Duke of Candia, and the Venetian administrative district of Crete became known as "Regno di Candia" (Kingdom of Candia). The city retained the name of Candia for centuries and the same name was often used to refer to the whole island of Crete as well. To secure their rule, the Venetians began in 1212 to settle families from Venice on Crete. The coexistence of two different cultures and the stimulus of the Italian Renaissance led to a flourishing of letters and the arts in Candia and Crete in general, that is today known as the Cretan Renaissance.

Ottoman era

During the Cretan War (1645–1669), the Ottomans besieged the city for 21 years, from 1648 to 1669, the longest siege in history up until that time. In its final phase, which lasted for 22 months, 70,000 Turks, 38,000 Cretans and slaves and 29,088 of the city's Christian defenders perished.[15] The Ottoman army under an Albanian grand vizier, Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed Pasha conquered the city in 1669.

Under the Ottomans, Kandiye (Ottoman Turkish قنديه) was the capital of Crete (Girit Eyâleti) until 1849, when Chania (Hanya) became the capital, and Kandiye became a sancak.[16] In Greek, it was commonly called Megalo Castro (Μεγάλο Κάστρο 'Big Castle').

During the Ottoman period, the harbour silted up, so most shipping shifted to Chania in the west of the island.

Modern era

An earthquake located off the northern coast of Crete on October 12, 1856, destroyed most of the over 3,600 homes in the city. Only 18 homes were left intact. The disaster claimed 538 victims in Heraklion.[17]

In 1898, the autonomous Cretan State was created, under Ottoman suzerainty, with Prince George of Greece as its High Commissioner and under international supervision. During the period of direct occupation of the island by the Great Powers (1898–1908), Candia was part of the British zone. At this time, the city was renamed "Heraklion", after the Roman port of Heracleum ("Heracles' city"), whose exact location is unknown.

In 1913, with the rest of Crete, Heraklion was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece. Heraklion became again capital of Crete in 1971, replacing Chania.[18]

Architecture, urban sculpture and fortifications

The oldest monument of architecture is palace in Knossos on the outskirts of the city.

Two largest medieval churches in the city were the Dominican church of St. Peter (built between 1248 and 1253) and the San Salvatore, belonging to the Augustinian Friars. The latter one stood in Kornaros Square, but was demolished in 1970.[19]

Other monuments of architecture from Venetian times include the Saint Mark's Basilica and the Renaissance loggia next to Lions Square (1626–28).

Around the historic city center of Heraklion there are also a series of defensive walls, bastions and other fortifications which were built earlier in the Middle Ages, but were completely rebuilt by the Republic of Venice. The fortifications managed to withstand the longest siege in history for 21 years, before the city fell to the Ottomans in 1669. The Koules Fortress (Castello a Mare), the ramparts and the arsenal dominate the port area.

Many fountains of the Venetian era are preserved, such as the Bembo fountain, the Priuli fountain, Palmeti fountain, Sagredo fountain and Morosini fountain in Lions Square (1628).

19th century architecture is represented by the St Titus Cathedral, built in 1869 as the Yeni Cami ("New Mosque") and the Agios Minas Cathedral (1862–95).

An example of modern architecture in Heraklion is the Heraklion Archaeological Museum built between 1937 and 1940 by architect Patroklos Karantinos.

Several sculptures, statues and busts commemorating significant events and figures of the city's and island's history, like El Greco, Vitsentzos Kornaros, Nikos Kazantzakis and Eleftherios Venizelos can be found around the city.

Knossos Palace

Knossos Palace Dominican church of St. Peter

Dominican church of St. Peter

Venetian Loggia

Venetian Loggia Morosini fountain in Lions Square

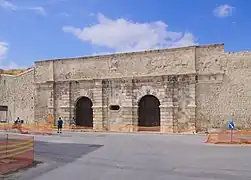

Morosini fountain in Lions Square Venetian walls, Pantokratoras Gate

Venetian walls, Pantokratoras Gate

Municipality

The municipality Heraklion was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following 5 former municipalities, that became municipal units:[20]

- Gorgolainis

- Heraklion

- Nea Alikarnassos

- Paliani

- Temenos

The municipality has an area of 244.613 km2, the municipal unit 109.026 km2.[21]

Neighborhoods

| • Agia Ekaterini | • Dimokratias | • Marathitis |

| • Agia Erini Chrisovalantou | • Estavromenos | • Mastabas |

| • Agia Marina | • Filothei | • Mesabelies |

| • Agia Triada | • Fortetsa | • Mpentevi |

| • Agios Dimitrios | • Ilioupoli | • Nea Alatsata |

| • Agios Ioannis Chostos | • Kamaraki | • Pananio |

| • Agios Minas | • Kaminia | • Papatitou Metochi |

| • Agios Titos | • Katsampas | • Pateles |

| • Akadimia | • Kenouria Porta | • Poros |

| • Ampelokipoi | • Kipoupoli | • Therissos |

| • Analipsi | • Komeno Mpenteni | • Tris Vagies |

| • Atsalenio | • Korakovouni | • Xiropotamos |

| • Chanioporta | • Koroni Magara | |

| • Chrisopigi | • Knossos | |

| • Dilina | • Lido |

Suburbs

.jpg.webp)

| • Agia Erini | • Finikia | • Ksirokabos |

| • Agia Marina | • Gazi urban area | • Malades |

| • Agioi Theodoroi | • Giofyrakia | • Nea Alikarnassos urban area |

| • Agios Syllas | • Gournes Temenous | • Sillamos |

| • Ammoudara | • Kallithea | • Skafidaras |

| • Amnisos | • Karteros | • Skalani |

| • Ano Kalesia | • Kato Kalesia | • Vasilies |

| • Athanati | • Kavrochori | • Voutes |

| • Dafnes | • Kollyvas |

Villages

Transportation

Port

Heraklion is an important shipping port and ferry dock. Travellers can take ferries and boats from Heraklion to destinations including Santorini, Ios Island, Paros, Mykonos, and Rhodes. There are direct ferries to Naxos, Karpathos, Kasos, Sitia, Anafi, Chalki and Diafani.[22] There are also several daily ferries to Piraeus, the port of Athens in mainland Greece. The port of Heraklion was built by Sir Robert McAlpine and completed in 1928.[23]

Airport

Heraklion International Airport, or Nikos Kazantzakis Airport is located about 5 kilometres (3 miles) east of the city. The airport is named after Heraklion native Nikos Kazantzakis, a writer and a philosopher. It is the second busiest airport of Greece after Athens International Airport, first in charter flights and the 59th busiest in Europe, because of Crete being a major holiday destination with 8,066,000 passengers in 2022 (List of the busiest airports in Europe).

The airfield is shared with the 126th Combat Group of the Hellenic Air Force.

Highway network

European route E75 runs through the city and connects Heraklion with the three other major cities of Crete: Agios Nikolaos, Chania, and Rethymno.

Public transit

Urban buses serve the city, with 39 different routes.[24] Intercity buses connect Heraklion to many major destinations in Crete.[25]

Railway

From 1922 to 1937, a working industrial railway connected the Koules in Heraklion to Xiropotamos for the construction of the harbor.[26]

In the summer of 2007, at the Congress of Cretan emigrants, held in Heraklion, two qualified engineers, George Nathenas (from Gonies, Malevizi Province) and Vassilis Economopoulos, recommended the development of a railway line in Crete, linking Chania, Rethymno and Heraklion, with a total journey time of 50 minutes (30 minutes between Heraklion and Rethymno, 20 minutes from Chania to Rethymno) and with provision for extensions to Kissamos, Kastelli Pediados (for the planned new airport), and Agios Nikolaos. No plans exist for implementing this idea.

Climate

Heraklion has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa in the Köppen climate classification). Summers are warm to hot and dry with clear skies. Dry hot days are often relieved by seasonal breezes. Winters are mild with moderate rain. Because Heraklion is further south than Athens, it has a warmer climate during winter but cooler during summer because of the Aegean Sea. The maximum temperature during the summer period is usually not more than 28 - 30 °C (Athens normal maximum temperature is about 5 °C higher). The minimum temperature record is -0.8 °C. Snowfalls are rare with the last significant snowfall with a measurable amount on the ground occurring in February 2004. [27]

| Climate data for Heraklion 1955-2010 (HNMS) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.9 (85.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.0 (100.4) |

41.3 (106.3) |

43.6 (110.5) |

44.5 (112.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

37.0 (98.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

28.5 (83.3) |

44.5 (112.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.3 (59.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.1 (53.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.9 (66.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.7 (47.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 91.0 (3.58) |

69.0 (2.72) |

53.4 (2.10) |

28.2 (1.11) |

13.4 (0.53) |

2.9 (0.11) |

0.8 (0.03) |

0.9 (0.04) |

16.7 (0.66) |

59.4 (2.34) |

59.6 (2.35) |

85.6 (3.37) |

480.9 (18.94) |

| Average rainy days | 16.0 | 13.6 | 11.4 | 7.6 | 4.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.8 | 7.5 | 10.6 | 15.2 | 91.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.4 | 66.4 | 65.9 | 62.3 | 61.2 | 57.0 | 57.1 | 59.1 | 61.9 | 65.7 | 67.9 | 68.3 | 63.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.9 | 132.3 | 181.5 | 234.8 | 298.5 | 356.2 | 368.3 | 343.5 | 275.8 | 206.9 | 145.5 | 115.4 | 2,778.6 |

| Source 1: HNMS[28][29] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: meteo-climat (extremes)[30] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Heraklion | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6.4 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [31] | |||||||||||||

Colleges, universities, libraries, and research centers

- University of Crete

- Hellenic Mediterranean University (HMU) (Former TEI)

- MBS College

- Foundation for Research & Technology - Hellas

- Nicolas Kitsikis Library

- Vikelaia Library

Culture

Museums

Arts

The Cultural and Conference Center of Heraklion is a centre for the performing arts.

Sports

The city is home to several sports clubs. Most notably, Heraklion hosts OFI and Ergotelis, two football clubs with earlier presence in the Greek Superleague, the top tier of the Greek football league system. Furthermore, the city is the headquarters of the Heraklion Football Clubs Association, which administers football in the entire region. Other notable sport clubs include Iraklio B.C. (basketball), Atsalenios (football) and Irodotos (football) in the suburbs of Atsalenio and Nea Alikarnassos respectively.

| Notable Sport clubs based in Heraklion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Club | Founded | Sports | Current Season |

| OFI | 1925 | Football, Basketball | Superleague, Greek C Basket League |

| Ergotelis | 1929 | Football, Basketball | Football League, Cretan Basket League |

| Iraklio | 1928 | Basketball | Cretan Basket League |

| Irodotos | 1932 | Football, Basketball | Football League, Cretan Basket League |

| Atsalenios | 1951 | Football | Gamma Ethniki |

Local TV stations

- Channel 4

- Creta Channel

- Kriti TV

- MyTV

Notable people

.jpg.webp)

Heraklion has been the home town of some of Greece's most significant people, including the novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (best known for Zorba the Greek), the poet and Nobel Prize winner Odysseas Elytis and the world-famous painter Domenicos Theotokopoulos (El Greco).

Literature

- Elli Alexiou (1894–1988) author

- Minás Dimákis (1913–1980) poet

- Odysseas Elytis (1911–1996) Nobel awarded poet

- Tess Fragoulis, Greek-Canadian author

- Rea Galanaki (1947–present) author

- Giritli Ali Aziz Efendi (1749–1798), author and diplomat

- Nikos Kazantzakis (1883–1957) author

- Menelaos Parlamas (1911–1997) author and scholar

- Pedro de Candia, (1485–1542) author and travel writer, recorded the Spanish Conquest of the Americas

- Stephanos Sahlikis (1330-after 1391) poet

- Lili Zografou (1922–1998) author

Scientists and academia

- Nicholas Kalliakis (1645–1707) Greek Cretan scholar and philosopher[33]

- Niccolò Comneno Papadopoli (1655–1740) lawyer, historian and librarian

- Andreas Musalus (c. 1665 – c. 1721) Greek Cretan professor of mathematics, philosopher and architectural theorist[34]

- Francesco Barozzi (1537–1604) mathematician and astronomer

- Joseph Solomon Delmedigo (1591-1655) rabbi, author, physician, mathematician and musical theorist

- Fotis Kafatos biologist, President of the European Research Council

- Spyros Kokotos (1933–present) architect

- Marcus Musurus (Markos Mousouros) (1470–1517) scholar and philosopher

- Peter of Candia also known as Antipope Alexander V: philosopher and scholar

- Joseph Sifakis (1946–present) computer scientist, co-recipient of the 2007 Turing Award

- Michael N. Katehakis (1952–present) applied mathematician and operations researcher at Rutgers University

- Gerasimos Vlachos (1607–1685), scholar

- Simone Stratigo (ca. 1733–1824), Greek mathematician and an Nautical science expert, whose family was from Heraklion (Candia)[35]

Painting and sculpture

- Theophanes (ca.1500–1559) painter of icons

- Michael Damaskinos (1530/35-1592/93) painter of icons

- Georgios Klontzas (1535-1608) painter

- El Greco (1541–1614) mannerist painter, sculptor and architect

- Yiannis Parmakelis (1932-), sculptor

- Andreas Ritzos (1422–1492) painter of icons

- Aristidis Vlassis (1947–2015) painter

- Konstantinos Volanakis (1837–1907) painter

Film industry

- Rika Diallina (1934-), actress and model, Miss Hellas

- Ilya Livykou (1919–2002), actress

- Sapfo Notara (1907–1985), actress

- Yannis Smaragdis (1946-), film director

Music

- Rena Kyriakou (1918–1994) pianist

- Francisco Leontaritis (Francesco Londarit) (1518–1572) composer

- Giannis Markopoulos (1939–) composer

- Myron Michailidis (1968–) conductor

- Manolis Rasoulis (1945–2011) lyrics writer

- Notis Sfakianakis (1959–) singer

- Lena Platonos, pianist

Spirituality

- Maria Papapetros - psychic, spiritual healer, spiritual consultant

Sports

- Kyle Hamilton (born 2001), American football player[36]

- Nikos Machlas (born 1973), footballer

- Georgios Samaras (born 1985), footballer

- Greg Massialas (born 1956), American fencer

- Michalis Karlis (born 2003), basketball player

- Giorgos Giakoumakis (Born 1994), footballer

Business

- Constantine Corniaktos (1517–1603) wine merchant and wealthiest man in the Eastern European city of Lviv[37]

- Gianna Angelopoulos-Daskalaki (1955-) business woman, lawyer and politician

Politics and law

- Emin Ali Bedir Khan (1851-1926), Kurdish diplomat

- Leonidas Kyrkos (1924–2011), politician

- Aristidis Stergiadis (1861–1950) High Commissioner of Smyrna

- Georgios Voulgarakis (1959-) conservative politician

- Romilos Kedikoglou (1940-) President of the Court of Cassation of Greece

Clergy

- Maximos Margunios (1549–1602), bishop of Cyrigo (Kythira)

- Kyrillos Loukaris (1572–1637) theologian, Pope & Patriarch of Alexandria as Cyril III and Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople as Cyril I

- Meletius Pegas, Pope & Patriarch of Alexandria

- Theodore II (1954-) Pope & Patriarch of Alexandria and all Africa

- Peter Phillarges (ca. 1339–1410) (also Pietro Di Candia, later Pope Alexander V)

- Makarios Griniezakis (1973-) Greek Orthodox Archbishop of the Holy Archdiocese of Australia

Fashion

- Maria Spiridaki (1984) fashion model and television presenter

International relations

Consulates

Twin towns and sister cities

Heraklion is twinned with:

Location

| Fira | ||

| Chania – Rethymno |  | Agios Nikolaos |

| Tympaki – Moires | Archanes | Ierapetra |

Gallery

View of the port from the fortress

View of the port from the fortress View of the port

View of the port The harbour

The harbour Α part of the Venetian harbour (used as shipyards)

Α part of the Venetian harbour (used as shipyards) The Phaistos Disk (2nd millennium BC) in Heraklion Archaeological Museum

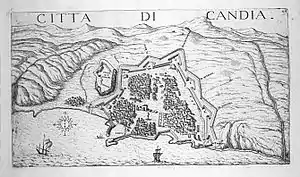

The Phaistos Disk (2nd millennium BC) in Heraklion Archaeological Museum Depiction of Candia, 1487

Depiction of Candia, 1487 Idomeneas fountain

Idomeneas fountain Jesus Gate, part of the Fortifications of Heraklion

Jesus Gate, part of the Fortifications of Heraklion Chanioporta and Pantokratoras Gate

Chanioporta and Pantokratoras Gate Bembo fountain

Bembo fountain Saint Catherine Church

Saint Catherine Church Depiction of the Siege of Candia

Depiction of the Siege of Candia St. Matthew of the Sinaites Byzantine church

St. Matthew of the Sinaites Byzantine church Theodoros Vardinogiannis Stadium, home ground of OFI FC

Theodoros Vardinogiannis Stadium, home ground of OFI FC Interior of the Fortress

Interior of the Fortress A monk shows the Saracens where to build Chandax

A monk shows the Saracens where to build Chandax Map of Heraklion and its fortifications in 1651

Map of Heraklion and its fortifications in 1651.jpg.webp) Minoan fresco depicting a bull leaping scene, found in Knossos, 1600-1400 BC, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Minoan fresco depicting a bull leaping scene, found in Knossos, 1600-1400 BC, Heraklion Archaeological Museum

See also

References

- ↑ "Βιογραφικό Σημείωμα Δημάρχου κου Βασίλη Λαμπρινού | Δήμαρχος | Ο Δήμος |". www.heraklion.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ↑ "Απογραφή Πληθυσμού - Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός" (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- ↑ appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu

- ↑ Pronunciation for Ηράκλειο

- ↑ "2021 Population-Housing Census". www.statistics.gr. Retrieved 2022-01-08.

- ↑ "Population on 1 January by age groups and sex - functional urban areas". Eurostat. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ↑ "Top 100 City Destination Ranking 2017". Market Research Blog. 2017-01-26. Archived from the original on 2020-11-29. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ↑ "Top 100 City Destinations Ranking: WTM London 2017 Edition". Market Research Blog. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ↑ Geerts, Wouter (2018). "Top 100 City Destinations 2018" (PDF). Euromonitor International.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Islam, s.v. Iķrīṭish

- ↑ It was in use by the local people by 1867, see Howe, Samuel Gridley (1868). The Cretan refugees and their American helpers. Boston: Lee and Shepard. p. 33 – via archive.org.

- ↑ Whitelaw, Todd; Morgan, Catherine (November 2009). "Crete". Archaeological Reports. 55: 79. doi:10.1017/s0570608400001307. ISSN 0570-6084. S2CID 231735198.

- ↑ Dimopoulou, N.; Wilson, D.E.; Day, P.M. (2007). "The Earlier Prepalatial Settlement of Poros-Katsambas: craft production and exchange at the harbour town of Knossos". In Day, P.M.; Doonan, R. (eds.). Metallurgy in the Early Bronze Age Aegean. Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology. Oxbow Books. pp. 84–97.

- ↑ "History of Heraklion in Crete island - Greeka.com". Greeka. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ↑ The War for Candia

- ↑ Tahir Sezen, Osmanlı Yer Adları, Ankara 2017, T.C. Başbakanlık Devlet Arşivleri Genel Müdürlüğü Yayın No: 26 s.v., p. 410

- ↑ National Geophysical Data Center / World Data Service (NGDC/WDS) (1972), Significant Earthquake Database (Data Set), National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA, doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K

- ↑ "Heraklion". visit-ancient-greece.com. Archived from the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Ilko, Krisztina (2021). "Recovering the Augustinian Convent of San Salvatore in Venetian Candia". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 72 (2): 259–263. doi:10.1017/S0022046920000755. S2CID 228866606. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ↑ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- ↑ "Heraklion ferry, compare prices, times and book tickets".

- ↑ "Sir Robert McAlpine". Grace's Guide. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ Iraklio urban buses

- ↑ "ΚΤΕΛ Ηρακλείου - Λασιθίου Κρήτης | Online Κράτηση εισιτηρίων για λεωφορεία - Δρομολόγια Λεωφορεία Κρήτης".

- ↑ Tzikas, Polykarpos; Konstantinos, Mamalakis; Tertipis, Dimitrios; Charitopoulos, Evangelos. «Μέσα σταθερής τροχιάς στην Κρήτη: Δίκτυα βιομηχανικών σιδηροδρόμων κατά το πρώτο μισό του 20ου αιώνα». Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Cretan Studies.

- ↑ "ΠΑΤΡΙΣ - ΑΡΧΕΙΟ ΗΛΕΚΤΡΟΝΙΚΗΣ ΕΚΔΟΣΗΣ". archive.patris.gr. Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- ↑ "Climatic Data for selected stations in Greece: Heraklion (Crete)". Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ↑ "Climate Atlas of Greece (for sunshine 1977-2002)". HNMS. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ↑ "STATION HERAKLION". meteo-climat. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ↑ "Heraklion, Greece - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ Lathrop C. Harper (1886). Catalogue / Harper (Lathrop C.) inc., New York, Issue 232. Lathrop C. Harper, Inc. p. 36. OCLC 11558801.

Calliachius (1645–1707) was born on Crete and went to Italy at an early age, where he soon became one of the outstanding teachers of Greek and Latin.

- ↑ Rose, Hugh James; Rose, Henry John; Wright, Thomas (1857). A new general biographical dictionary, Volume 5. T. Fellowes. p. 425. OCLC 309809847.

CALLIACHI, (Nicholas,) a native of Candia, where he was born in 1645. He studied at Rome for ten years, at the end of which time he was made doctor of philosophy and theology. In 1666 he was invited to Venice, to take the chair of professor of the Greek and Latin languages, and of the Aristotelic philosophy; and in 1677 he was appointed professor of belles-lettres at Padua, where he died in 1707. His works on antiquities are valuable, and have been published by the marquis Poloni in the third volume of his Supplement to the Thesaurus Antiquitatum.

- ↑ Convegno internazionale nuove idee e nuova arte nell '700 italiano, Roma, 19–23 maggio 1975. Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. 1977. p. 429. OCLC 4666566.

Nicolò Duodo riuniva alcuni pensatori ai quali Andrea Musalo, oriundo greco, professore di matematica e dilettante di architettura chiariva le nuove idée nella storia dell'arte.

- ↑ Carlo Capra; Franco Della Peruta; Fernando Mazzocca (2002). Napoleone e la repubblica italiana: 1802–1805. Skira. p. 200. ISBN 978-88-8491-415-6.

Simone Stratico, nato a Zara nel 1733 da famiglia originaria di Creta (abbandonata a seguito della conquista turca del 1669)

- ↑ "Notre Dame RB Mick Assaf: Mick's Mickstape Season 2 Volume 1".

- ↑ I︠A︡roslav Dmytrovych Isai︠e︡vych (2006). Voluntary brotherhood: confraternities of laymen in early modern Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press. p. 47. ISBN 1-894865-03-0.

…the Greek merchants Constantine Korniakt and Manolis Arphanes Marinetos are added. This second redaction appeared no earlier than 1589, as wealthy Greeks began to join the confraternity at a later date, once it had expanded its activities. Korniakt was actually the wealthiest man in Lviv: he traded in Eastern, Western, and local goods, collected customs duty on behalf of the king, and owned a number of villages.

- ↑ "Limassol Twinned Cities". Limassol (Lemesos) Municipality. Archived from the original on 2013-04-01. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "Cu ce oraşe este înfrăţit municipiul Constanţa?". Ziua de Constanța. 7 April 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ↑ "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

External links

Heraklion travel guide from Wikivoyage

Heraklion travel guide from Wikivoyage- Municipality of Heraklion

- Heraklion information

- Heraklion - The Greek National Tourism Organization

- Vikelaia Library

- Heraklion at Curlie

- Old maps of Heraklion Archived 2022-03-16 at the Wayback Machine - Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, The National Library of Israel, in Historic Cities Archived 2022-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

.jpg.webp)