Kamakura

鎌倉市 | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: Tsurugaoka Hachimangū, Daibutsu (giant Buddha) at Kōtoku-in, Kenchō-ji, Kamakura-gū (Ōtōnomiya), and Egara Tenjin Shrine | |

Flag  Seal | |

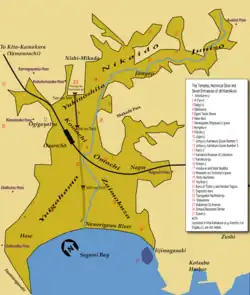

Kamakura in Kanagawa Prefecture | |

Kamakura  Kamakura Kamakura (Kanto Area)  Kamakura Kamakura (Kanagawa Prefecture) | |

| Coordinates: 35°19′11″N 139°33′09″E / 35.31972°N 139.55250°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Kanagawa Prefecture |

| First official recorded | 1063 |

| City Settled | November 3, 1939 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Takashi Matsuo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 39.67 km2 (15.32 sq mi) |

| Population (September 1, 2020) | |

| • Total | 172,929 |

| • Density | 4,400/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| – Tree | Yamazakura (Prunus jamasakura) |

| – Flower | Gentian |

| Phone number | 0467-23-3000 |

| Address | 18-10 Onarimachi, Kamakura-shi, Kanagawa-ken 248-8686 |

| Website | Official website |

Kamakura (鎌倉, Kamakura, [kamakɯɾa] ⓘ) officially Kamakura City (鎌倉市, Kamakura-shi) is a city of Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan. It is located in the Kanto region on the island of Honshu. The city has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 people per km² over the total area of 39.67 km2 (15.32 sq mi). Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

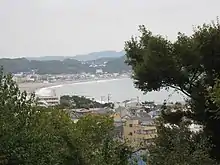

Kamakura is one of Japan's ancient capitals, alongside Kyoto and Nara, and it served as the seat of the Kamakura shogunate from 1185 to 1333, established by Minamoto no Yoritomo. It was the first military government in Japan's history. After the downfall of the shogunate, Kamakura saw a temporary decline. However, during the Edo period, it regained popularity as a tourist destination among the townspeople of Edo. Despite suffering significant losses of historical and cultural assets due to the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923, Kamakura continues to be one of the major tourist attractions in the Kanto region, known for its historical landmarks such as Tsurugaoka Hachimangū and the Great Buddha of Kamakura.

| Kamakura | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Kamakura" in kanji | |||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||

| Kanji | 鎌倉 | ||||||

| Hiragana | かまくら | ||||||

| |||||||

Geography

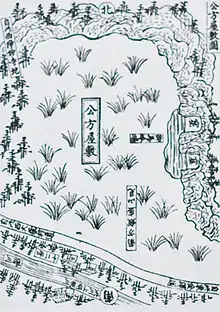

Surrounded to the north, east, and west by hills and to the south by the open water of Sagami Bay, Kamakura is a natural fortress.[1] Before the construction of several tunnels and modern roads that now connect it to Fujisawa, Ofuna, and Zushi, on land it could be entered only through narrow artificial passes, among which the seven most important were called Kamakura's Seven Entrances (鎌倉七口), a name sometimes translated as 'Kamakura's Seven Mouths'. The natural fortification made Kamakura an easily defensible stronghold.[1]

Before the opening of the Entrances, access on land was so difficult that the Azuma Kagami reports that Hōjō Masako came back to Kamakura from a visit to Sōtōzan temple in Izu bypassing by boat the impassable Inamuragasaki cape and arriving in Yuigahama.[1] Again according to the Azuma Kagami, the first of the Kamakura shōgun, Minamoto no Yoritomo, chose it as a base partly because it was his ancestors' land (his yukari no chi), partly because of these physical characteristics.[1]

To the north of the city stands Mt. Genji (源氏山, Genjiyama) (92 m (302 ft)), which then passes behind the Daibutsu and reaches Inamuragasaki and the sea.[2]

From the north to the east, Kamakura is surrounded by Mt. Rokkokuken (六国見) (147 m (482 ft)), Mt. Ōhira (大平山) (159 m (522 ft)), Mt. Jubu (鷲峰山) (127 m (417 ft)), Mt. Tendai (天台山) (141 m (463 ft)), and Mt. Kinubari (衣張山) (120 m (390 ft)), which extend all the way to Iijimagasaki and Wakae Island, on the border with Kotsubo and Zushi.[2] From Kamakura's alluvional plain branch off numerous narrow valleys like the Urigayatsu, Shakadōgayatsu, Ōgigayatsu, Kamegayatsu, Hikigayatsu, and Matsubagayatsu valleys.[lower-alpha 1]

Kamakura is crossed by the Namerigawa river, which goes from the Asaina Pass in northern Kamakura to the beach in Yuigahama for a total length of about 8 kilometers (5 mi). The river marks the border between Zaimokuza and Yuigahama.

In administrative terms, the municipality of Kamakura borders with Yokohama to the north, with Zushi to the east, and with Fujisawa to the west.[2] It includes many areas outside the Seven Entrances as Yamanouchi, Koshigoe (腰越), Shichirigahama, and Ofuna, and is the result of the fusion of Kamakura proper with the cities of Koshigoe, absorbed in 1939, Ofuna, absorbed in 1948, and with the village of Fukasawa, absorbed in 1948.

Kita-Kamakura (Yamanouchi)

Northwest of Kamakura lies Yamanouchi, commonly called Kita-Kamakura because of the presence of East Japan Railway Company's (JR) Kita-Kamakura Station. Yamanouchi, however, was technically never a part of historical Kamakura since it is outside the Seven Entrances. Yamanouchi was the northern border of the city during the shogunate,[3] and the important Kobukorozaka and Kamegayatsu Passes, two of Kamakura's Seven Entrances, led directly to it. Its name at the time used to be Sakado-gō (尺度郷).[4] The border post used to lie about a hundred meters past today's Kita-Kamakura train station in Ofuna's direction.[3]

Although very small, Yamanouchi is famous for its traditional atmosphere and the presence, among others, of three of the five highest-ranking Rinzai Zen temples in Kamakura, the Kamakura Gozan (鎌倉五山). These three great temples were built here because Yamanouchi was the home territory of the Hōjō clan, a branch of the Taira clan which ruled Japan for 150 years. Among Kita-Kamakura's most illustrious citizens were artist Isamu Noguchi and movie director Yasujirō Ozu. Ozu is buried at Engaku-ji.

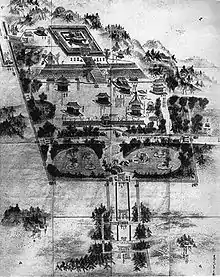

Wakamiya Ōji and the shogunate's six avenues

Kamakura's defining feature is Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, a Shinto shrine in the center of the city. A 1.8-kilometre (1.1 mi) road (参道, sandō) runs from Sagami Bay directly to the shrine. This road is known as Wakamiya Ōji, the city's main street. Built by Minamoto no Yoritomo as an imitation of Kyoto's Suzaku Ōji, Wakamiya Ōji used to be much wider, delimited on both sides by a 3-metre-deep (9.8 ft) canal and flanked by pine trees.[5]

Walking from the beach toward the shrine, one passes through three torii, or Shinto gates, called respectively Ichi no Torii ('first gate'), Ni no Torii ('second gate') and San no Torii ('third gate'). Between the first and the second lies Geba Yotsukado which, as the name indicates, was the place where riders had to get off their horses in deference to Hachiman and his shrine.[5]

Approximately 100 metres (330 ft) after the second torii, the dankazura, a raised pathway flanked by cherry trees that marks the center of Kamakura, begins. The dankazura becomes gradually wider, giving the effect of looking longer than it really is when viewed from the shrine. Its entire length is under the direct administration of the shrine. Minamoto no Yoritomo made his father-in-law Hōjō Tokimasa and his men carry by hand the stones to build it to pray for the safe delivery of his son Yoriie. The dankazura used to go all the way to Geba, but it was drastically shortened during the 19th century to make way for the newly constructed Yokosuka railroad line.[5]

In Kamakura, wide streets are known as Ōji (大路), narrower streets as Kōji (小路), the small streets that connect the two as zushi (辻子), and intersections as tsuji (辻). Komachi Ōji and Ima Kōji run respectively east and west of Wakamiya Ōji, while Yoko Ōji, the road that passes right under San no Torii, and Ōmachi Ōji, which goes from Kotsubo to Geba and Hase, run in the east–west direction.[5] Near the remains of Hama no Ōtorii runs Kuruma Ōji Avenue (also called Biwa Koji). These six streets (three running north to south and three east to west) were built at the time of the shogunate and are all still under heavy use. The only one to have been modified is Kuruma Ōji, a segment of which has disappeared.

Demographics

Per Japanese census data,[6][7] the population of Kamakura has remained relatively steady in recent decades.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 29,692 | — |

| 1930 | 42,206 | +42.1% |

| 1940 | 56,598 | +34.1% |

| 1950 | 85,391 | +50.9% |

| 1960 | 98,617 | +15.5% |

| 1970 | 139,249 | +41.2% |

| 1980 | 172,629 | +24.0% |

| 1990 | 174,307 | +1.0% |

| 2000 | 167,583 | −3.9% |

| 2010 | 174,314 | +4.0% |

| 2020 | 172,710 | −0.9% |

History

Early history

The earliest traces of human settlements in the area date back at least 10,000 years. Obsidian and stone tools found at excavation sites near Jōraku-ji were dated to the Old Stone Age (between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago). During the Jōmon period, the sea level was higher than now and all the flat land in Kamakura up to Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū and, further east, up to Yokohama's Totsuka-ku and Sakae-ku was under water. Thus, the oldest pottery fragments found come from hillside settlements of the period between 7500 BC and 5000 BC. In the late Jōmon period the sea receded and civilization progressed. During the Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD), the sea receded further almost to today's coastline, and the economy shifted radically from hunting and fishing to farming.[8]

The Azuma Kagami describes pre-shogunate Kamakura as a remote, forlorn place, but there is reason to believe its writers simply wanted to give the impression that prosperity had been brought there by the new regime.[9] To the contrary, it is known that by the Nara period (about 700 AD) there were both temples and shrines. Sugimoto-dera for example was built during this period and is therefore one of the city's oldest temples.[8] The town was also the seat of area government offices and the point of convergence of several land and marine routes. It seems therefore only natural that it should have been a city of a certain importance, likely to attract Yoritomo's attention.[9]

Etymology

The name Kamakura appears in the Kojiki of 712,[10][11] and is also mentioned in the c. 8th century Man'yōshū[12][13] as well as in the Wamyō Ruijushō[14] of 938. However, the city clearly appears in the historical record only with Minamoto no Yoritomo's founding of the Kamakura shogunate in 1192.

There are various hypotheses about the origin of the name. According to the most likely theory, Kamakura, surrounded as it is on three sides by mountains, was likened both to a cooking hearth (竃, kamado, kama) and to a warehouse (倉, kura), because both only have one side open.[10]

Another and more picturesque explanation is a legend, relating how Fujiwara no Kamatari stopped at Yuigahama on his way to today's Ibaraki Prefecture, where he wanted to pray at the Kashima Shrine for the fall of Soga no Iruka. He dreamed of an old man who promised his support, and upon waking, he found next to his bed a type of spear called a kamayari. Kamatari enshrined it in a place called Ōkura. Kamayari plus Ōkura then turned into the name Kamakura.[10] However, this and similar legends appear to have arisen only after Kamatari's descendant Fujiwara no Yoritsune became the fourth shōgun of the Kamakura shogunate in 1226, some time after the name Kamakura appears in the historical record.[15] It used to be also called Renpu (鎌府) (short for Kamakura Shogunate (鎌倉幕府, Kamakura Bakufu)).

Kamakura period

The extraordinary events, the historical characters and the culture of the twenty years which go from Minamoto no Yoritomo's birth to the assassination of the last of his sons have been throughout Japanese history the background and the inspiration for countless poems, books, jidaigeki TV dramas, Kabuki plays, songs, manga and even videogames; and are necessary to make sense of much of what one sees in today's Kamakura.

Yoritomo, after the defeat and almost complete extermination of his family at the hands of the Taira clan, managed in the space of a few years to go from being a fugitive hiding from his enemies inside a tree trunk to being the most powerful man in the land. Defeating the Taira clan, Yoritomo became de facto ruler of much of Japan and founder of the Kamakura shogunate, an institution destined to last 141 years and to have immense repercussions over the country's history.

The Kamakura shogunate era is called by historians the Kamakura period and, although its end is clearly set (Siege of Kamakura (1333)), its beginning is not. Different historians put Kamakura's beginning at a different point in time within a range that goes from the establishment of Yoritomo's first military government in Kamakura (1180) to his elevation to the rank of Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍) in 1192.[17] It used to be thought that during this period, effective power had moved completely from the Emperor in Kyoto to Yoritomo in Kamakura, but the progress of research has revealed this was not the case.[17] Even after the consolidation of the shogunate's power in the east, the Emperor continued to rule the country, particularly its west.[17] However, it is undeniable that Kamakura had a certain autonomy and that it had surpassed the technical capital of Japan politically, culturally and economically.[17] The shogunate even reserved for itself an area in Kyoto called Rokuhara (六波羅) where lived its representatives, who were there to protect its interests.[17]

In 1179, Yoritomo married Hōjō Masako, an event of far-reaching consequences for Japan. In 1180, he entered Kamakura, building his residence in a valley called Ōkura (in today's Nishi Mikado). The stele on the spot reads:

737 years ago, in 1180, Minamoto no Yoritomo built his mansion here. Consolidated his power, he later ruled from home, and his government was therefore called Ōkura Bakufu (大蔵幕府). He was succeeded by his sons Yoriie and Sanetomo, and this place remained the seat of the government for 46 years until 1225, when his wife Hōjō Masako died. It was then transferred to Utsunomiya Tsuji (宇津宮辻).

Erected in March 1917 by the Kamakurachō Seinenkai

In 1185, his forces, commanded by his younger brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune, vanquished the Taira and in 1192 he received from Emperor Go-Toba the title of Sei-i Taishōgun.[18] Yoshitsune's power would however cause Yoritomo's envy; the relationship between the brothers soured, and in 1189 Yoritomo was given Yoshitsune's head pickled in liquor. For the same reason, in 1193 he had his other brother Noriyori killed. Power was now firmly in his hands, but the Minamoto dynasty and its power however were to end as quickly and unexpectedly as they had started.

In 1199, Yoritomo died falling from his horse at the age of 51, and was buried in a temple that had until then housed his tutelary goddess.[19] He was succeeded by his 17-year-old son Minamoto no Yoriie under the regency of his maternal grandfather Hōjō Tokimasa. A long and bitter fight ensued in which entire clans like the Hatakeyama, the Hiki, and the Wada were wiped out by the Hōjō who wished to get rid of Yoritomo's supporters and consolidate their power. Yoriie did become head of the Minamoto clan and was regularly appointed shōgun in 1202 but by that time, real power had already fallen into the hands of the Hōjō clan.[18] Yoriie plotted to take back his power, but failed and was assassinated on July 17, 1204.[18] His six-year-old first son Ichiman had already been killed during political turmoil in Kamakura, while his second son Yoshinari at age six was forced to become a Buddhist priest under the name Kugyō. From then on all power would belong to the Hōjō, and the shōgun would be just a figurehead. Since the Hōjō were part of the Taira clan, it can be said that the Taira had lost a battle, but in the end had won the war.

Yoritomo's second son and third shōgun Minamoto no Sanetomo spent most of his life staying out of politics and writing poetry, but was nonetheless assassinated in February 1219 by his nephew Kugyō under the giant ginkgo tree whose trunk still stood at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū until it was uprooted by a storm in the early hours of March 10, 2010.[18] Kugyō himself, the last of his line, was beheaded as a punishment for his crime by the Hōjō just hours later. Barely 30 years into the shogunate, the Seiwa Genji dynasty who had created it in Kamakura had ended.[18]

In 1293, a severe earthquake killed 23,000 people and seriously damaged the city. In the confusion following the quake, Hōjō Sadatoki, the Shikken of the Kamakura shogunate, carried out a purge against his subordinate Taira no Yoritsuna. In what is referred to as the Heizen Gate Incident, Yoritsuna and 90 of his followers were killed.

The Hōjō regency however continued until Nitta Yoshisada destroyed it in 1333 at the Siege of Kamakura. It was under the regency that Kamakura acquired many of its best and most prestigious temples and shrines, for example Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Kenchō-ji, Engaku-ji, Jufuku-ji, Jōchi-ji, and Zeniarai Benten Shrine. The Hōjō family crest in the city is therefore still ubiquitous.

From the middle of the thirteenth century, the fact that the vassals (the gokenin) were allowed to become de facto owners of the land they administered, coupled to the custom that all gokenin children could inherit, led to the parcelization of the land and to a consequent weakening of the shogunate. This, and not lack of legitimacy, was the primary cause of the Hōjō's fall.

According to The Institute for Research on World-Systems,[20] Kamakura was the 4th largest city in the world in 1250 AD, with 200,000 people, and Japan's largest, eclipsing Kyoto by 1200 AD. Yet, despite Kamakura's annihilation of Kyoto-based political and military power at the Battle of Dan-no-ura in 1185, and the failure of the Emperor to free himself from Kamakura's control during the Jōkyū War, Takahashi (2005) has questioned whether Kamakura's nationwide political hegemony actually existed.[17] Takahashi claims that if Kamakura ruled the Kantō, not only was the Emperor in fact still the ruler of Kansai, but during this period the city was in many ways politically and administratively still under the ancient capital of Kyoto.[17] Kamakura was simply a rival center of political, economic and cultural power in a country that had Kyoto as its capital.[17]

Fall of the Kamakura shogunate

On July 3, 1333,[21] warlord Nitta Yoshisada, who was an Emperor loyalist, attacked Kamakura to reestablish imperial rule. After trying to enter by land through the Kewaizaka Pass and the Gokuraku-ji Pass, he and his forces waited for a low tide, bypassed the Inamuragasaki cape, entered the city and took it.[22]

In accounts of that disastrous Hōjō defeat it is recorded that nearly 900 Hōjō samurai, including the last three Regents, committed suicide at their family temple, Tōshō-ji, whose ruins have been found in today's Ōmachi. Almost the entire clan vanished at once, the city was sacked and many temples were burned.[lower-alpha 2] Many simple citizens imitated the Hōjō, and an estimated total of over 6,000 died on that day of their own hand.[22] In 1953, 556 skeletons of that period were found during excavations near Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū's Ichi no Torii in Yuigahama, all of people who had died of a violent death, probably at the hand of Nitta's forces.

Muromachi and Edo periods

The fall of Kamakura marks the beginning of an era in Japanese history characterized by chaos and violence called the Muromachi period. Kamakura's decline was slow, and in fact the next phase of its history, in which, as the capital of the Kantō region, it dominated the east of the country, lasted almost as long as the shogunate had.[23] Kamakura would come out of it almost completely destroyed.[24]

The situation in Kantō after 1333 continued to be tense, with Hōjō supporters staging sporadic revolts here and there.[25] In 1335, Hōjō Tokiyuki, son of last regent Takatoki, tried to re-establish the shogunate by force and defeated Kamakura's de facto ruler Ashikaga Tadayoshi in Musashi, in today's Kanagawa Prefecture.[26] He was in his turn defeated in Koshigoe by Ashikaga Takauji, who had come in force from Kyoto to help his brother.[24][26]

Takauji, founder of the Ashikaga shogunate which, at least nominally, ruled Japan during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, at first established his residence at the same site in Kamakura where Yoritomo's Ōkura Bakufu had been, but in 1336 he left Kamakura in charge of his son Yoshiakira and went west in pursuit of Nitta Yoshisada.[25] The Ashikaga then decided to permanently stay in Kyoto, making Kamakura instead the capital of the Kamakura-fu (鎌倉府) (or Kantō-fu (関東府)), a region including the provinces of Sagami, Musashi, Awa, Kazusa, Shimōsa, Hitachi, Kozuke, Shimotsuke, Kai, and Izu, to which were later added Mutsu and Dewa, making it the equivalent to today's Kanto, plus the Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures.[23]

Kamakura's ruler was called kantō kubō, a title equivalent to shōgun assumed by Ashikaga Takauji's son Motouji after his nomination to Kantō kanrei, or deputy shōgun, in 1349.[27] Motouji transferred his original title to the Uesugi family, which had previously held the hereditary title of shitsuji (執事), and would thereafter provide the Kantō kanrei.[27] Motouji had been sent by his father because this last understood the importance of controlling the Kantō region and wanted to have an Ashikaga in power there, but the administration in Kamakura was from the beginning characterized by its rebelliousness, so the shōgun's idea never really worked and actually backfired.[28] The kantō kubō era is essentially a struggle for the shogunate between the Kamakura and the Kyoto branches of the Ashikaga clan, because both believed they had a valid claim to power.[29] In the end, Kamakura had to be retaken by force in 1454.[27] The five kubō recorded by history, all of Motouji's bloodline, were in order Motouji himself, Ujimitsu, Mitsukane, Mochiuji and Shigeuji.[27] The last kubō had to escape to Koga, in today's Ibaraki prefecture, and he and his descendants thereafter became known as the koga kubō. According to the Shinpen Kamakurashi, a guide book published in 1685, more than two centuries later the spot where the kubō's mansion had been was still left empty by local peasants in the hope he may one day return.

A long period of chaos and war followed the departure of the last kantō kubō (the Sengoku period). Kamakura was heavily damaged in 1454 and almost completely burned during the Siege of Kamakura (1526).[24] Many of its citizens moved to Odawara when it came to prominence as the home town of the Later Hōjō clan.[22] The final blow to the city was the decision taken in 1603 by the Tokugawa shōgun to move the capital to nearby Edo, the place now called Tokyo.[22] The city never recovered and gradually returned to be the small fishing village it had been before Yoritomo's arrival.[22] Edmond Papinot's Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan, published in 1910 during the late Meiji period, describes it as follows:

Kamakura. A small town (7250 inh.) in Sagami which for several centuries was the second capital of Japan. [...] At present there remain of the splendor of the past only the famous Daibutsu and the Tsurugaoka Hachiman temple.[30]

Meiji period and the 20th century

After the Meiji Restoration, Kamakura's great cultural assets, its beach, and the mystique that surrounded its name made it as popular as it is now, and for essentially the same reasons.[22] The destruction of its heritage nonetheless did not stop: during the anti-Buddhist violence of 1868 (haibutsu kishaku) that followed the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri) many of the city temples were damaged.[31] In other cases, because mixing the two religions was now forbidden, shrines or temples had to give away some of their treasures, thus damaging their cultural heritage and decreasing the value of their properties.[31] Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū's giant Niō (仁王) (the two wooden warden gods usually found at the sides of a Buddhist temple's entrance), for example, being objects of Buddhist worship and therefore illegal where they were, were brought to Jufuku-ji, where they still are.[22][32]

The shrine also had to destroy Buddhism-related buildings, for example its tahōtō tower, its midō (御堂), and its shichidō garan. [31] Some Buddhist temples were simply closed, like Zenkō-ji, to which the now-independent Meigetsu-in used to belong.[33]

In 1890, the railroad, which until then had arrived just to Ofuna, reached Kamakura bringing in tourists and new residents, and with them a new prosperity.[22] Part of the ancient Dankazura (see above) was removed to let the railway system's new Yokosuka Line pass.

The damage caused by time, centuries of neglect, politics, and modernization was further compounded by nature in 1923. The epicenter of the Great Kantō earthquake that year was deep beneath Izu Ōshima Island in Sagami Bay, a short distance from Kamakura. Tremors devastated Tokyo, the port city of Yokohama, and the surrounding prefectures of Chiba, Kanagawa, and Shizuoka, causing widespread damage throughout the Kantō region.[34] It was reported that the sea receded at an unprecedented velocity, and then waves rushed back towards the shore in a great wall of water over seven meters high, drowning some and crushing others beneath an avalanche of waterborne debris. The total death toll from earthquake, tsunami, and fire exceeded 2,000 victims.[35] Large sections of the shore simply slid into the sea; and the beach area near Kamakura was raised up about six-feet; or in other words, where there had only been a narrow strip of sand along the sea, a wide expanse of sand was fully exposed above the waterline.[36]

Many temples founded centuries ago have required restoration, and it is for this reason that Kamakura has just one National Treasure in the building category (the Shariden at Engaku-ji). Much of Kamakura's heritage was for various reasons over the centuries first lost and later rebuilt.[37]

Nichiren in Kamakura

Kamakura is known among Buddhists for having been the cradle of Nichiren Buddhism during the 13th century. Founder Nichiren was not a native; he was born in Awa Province, in today's Chiba Prefecture. But it was only natural for a preacher to come here because the city was the political centre of the country at the time.[38] Nichiren settled down in a straw hut in the Matsubagayatsu (literally transl. pine needle valley)[39] district, where three temples (Ankokuron-ji, Myōhō–ji, and Chōshō-ji), have been fighting for centuries for the honour of being the true heir of the master.[38] During his turbulent life Nichiren came and went, but Kamakura always remained at the heart of his religious activities. It is here that, when he was about to be executed by the Hōjō Regent for being a troublemaker, he was allegedly saved by a miracle; it is also in Kamakura that he wrote his famous Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論), or 'Treatise on Peace and Righteousness', and that legend says he was rescued and fed by monkeys. Kamakura is also where he preached.[38]

Some Kamakura locations important to Nichiren Buddhism are:

- The three temples in Matsubagayatsu

Ankokuron-ji claims to have on its grounds the cave where the master, with the help of a white monkey, hid from his persecutors.[38] (However Hosshō-ji in Zushi's Hisagi district makes the same claim, and with a better historical basis.)[40][41] Within Ankokuron-ji lie also the spot where Nichiren used to meditate while admiring Mount Fuji, the place where his disciple Nichiro was cremated, and the cave where he is supposed to have written his Risshō Ankoku Ron.[38]

Nearby Myōhō–ji (also called Koke-dera or 'Temple of Moss'), a much smaller temple, was erected in an area where Nichiren had his home for 19 years.[38] The third Nichiren temple in Nagoe, Chōshō-ji, also claims to lie on the very spot where it all started.

- The Nichiren Tsujiseppō Ato (日蓮聖人辻説法跡) on Komachi Ōji in the Komachi district contains the very stone from which he used to harangue the crowds, claiming that the various calamities that were afflicting the city at the moment were due to the moral failings of its citizens.[38]

- The former execution ground at Katase's Ryūkō-ji where Nichiren was about to be beheaded (an event known to Nichiren's followers as the Tatsunokuchi Persecution (龍ノ口法難)), and where he was miraculously saved when thunder struck the executioner.[38] Nichiren had been condemned to death for having written the Risshō Ankoku Ron.[42] Every year, on September 12, Nichiren devotees gather to celebrate the anniversary of the miracle.[43]

- The Kesagake no Matsu (袈裟掛けの松), the pine tree on the roads between Harisuribashi and Inamuragasaki from which Nichiren hanged his kesa (a Buddhist stole) while on his way to Ryūkō-ji.[42] The original pine tree however died long ago and, after having been replaced many times, now no longer exists.[42]

Notable locations

Kamakura has many historically significant Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, some of them, like Sugimoto-dera, over 1,200 years old. Kōtoku-in, with its monumental outdoor bronze statue of Amida Buddha, is the most famous. A 15th-century tsunami destroyed the temple that once housed the Great Buddha, but the statue survived and has remained outdoors ever since. This iconic Daibutsu is arguably amongst the few images which have come to represent Japan in the world's collective imagination. Kamakura also hosts the so-called Five Great Zen Temples (the Kamakura Gozan).

The architectural heritage of Kamakura is almost unmatched, and the city has proposed some of its historic sites for inclusion in UNESCO's World Heritage Sites list. Although much of the city was devastated in the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, damaged temples and shrines, founded centuries ago, have since been carefully restored.

Some of Kamakura's highlights are:

- The Asaina Pass and its Kumano Jinja

- Ankokuron-ji

- An'yō-in

- Chōju-ji, one of Ashikaga Takauji's two bodaiji (funeral temples)

- Engaku-ji, ranked Number Two among Kamakura's Great Zen Temples

- Hatakeyama Shigeyasu's grave

- Hōkai-ji, dedicated to the memory of the Hōjō clan

- Jōchi-ji, ranked Number Four among Kamakura's Great Zen Temples

- Jōmyō-ji temple, ranked Number Five among Kamakura's Great Zen Temples

- Jufuku-ji, ranked Number Three among Kamakura's Great Zen Temples

- Hase-dera

- Kamakura-gū in Nikaidō, built on the spot where Prince Morinaga, son of Emperor Go-Daigo, was imprisoned and then beheaded by Ashikaga Tadayoshi in 1335.

- The Kamakura Museum of Literature, the former villa of Marquises Maeda

- Kamakura Museum of National Treasures

- Kanagawa Prefectural Ofuna Botanical Garden

- Kenchō-ji, ranked Number One among Kamakura's Great Zen Temples and, together with Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, the pride of the city

- Kōmyō-ji

- Kōtoku-in and its Great Buddha

- Meigetsu-in

- Moto Hachiman

- Myōhon-ji

- Ōfuna Kannon[44]

- Katase's Ryūkō-ji

- Sasuke Inari Shrine and Hidden Village

- The Shakadō Pass (see description below)

- Sugimoto-dera

- Tamanawa Castle, Castle ruins of Later Hōjō clan

- Tatsunokuchi, where Mongol emissaries were beheaded and buried.

- Tōkei-ji, famous in the past as a refuge for battered women

- Tomb of Minamoto no Yoritomo

- Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, symbol of the city

- Wakamiya Ōji Avenue with its three torii and cherry trees

- Yuigahama, a popular beach

- Zeniarai Benzaiten Shrine, where visitors go to wash their coins

- Zuisen-ji, funeral temple of the Ashikaga kubō, rulers in Kamakura during the early Muromachi period

Festivals and other events

Kamakura has many festivals (matsuri (祭り)) and other events in each of the seasons, usually based on its rich historical heritage. They are often sponsored by private businesses and, unlike those in Kyoto, they are relatively small-scale events attended mostly by locals and a few tourists.[45] January in particular has many because it is the first month of the year, so authorities, fishermen, businesses and artisans organize events to pray for their own health and safety, and for a good and prosperous working year. Kamakura's numerous temples and shrines, first among them city symbols Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū and Kenchō-ji, organize many events too, bringing the total to over a hundred.[45]

January

- January 4: Chōna-hajimeshiki (手斧初式) at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū: This event marks the beginning of the working year for local construction workers who, for the ceremony, use traditional working tools.[45] The festival also commemorates Minamoto no Yoritomo, who ordered the reconstruction of the main building of the shrine after it was destroyed by fire in 1191.[45] The ceremony takes place at 1:00 pm at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū.[46]

February

- Day before the first day of spring (usually February 3): Setsubun Matsuri (節分祭) at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Kenchō-ji, Hase-dera, Kamakura-gū, etc.: Celebration of the end of winter.[45] Soybeans are scattered in the air to ensure good luck.[45]

April

- 2nd to 3rd Sunday: Kamakura Matsuri at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū and other locations: A whole week of events that celebrate the city and its history.[45]

May

- May 5: Kusajishi (草鹿) at the Kamakura Shrine: Archers in samurai gear shoot arrows at a straw deer while reciting old poems.[45]

August

September

Shakadō Pass

Besides the Seven Entrances there is another great pass in the city, the huge Shakadō Pass (釈迦堂切通), which connects Shakadōgayatsu[39] to the Ōmachi and Nagoe (formerly called Nagoshi) districts.

According to the plaque near the pass itself, the name derives from the fact that third Shikken Hōjō Yasutoki built here a Shakadō (a Buddhist temple devoted to Shakyamuni) dedicated to his father Yoshitoki's memory. The original location of the temple is unclear, but it was closed some time in the middle Muromachi period.[47] The Shaka Nyorai statue that is supposed to have been its main object of cult has been declared an Important Cultural Property and is conserved at Daien-ji in Meguro, Tokyo.[47]

Although important, the pass was not considered one of the Entrances because it connected two areas both fully within Kamakura.[5] Its date of creation is unclear, as it is not explicitly mentioned in any historical record, and it could be therefore recent.[5] It seems very likely however that a pass which connected the Kanazawa Road to the Nagoe area called Inukakezaka (犬懸坂) and mentioned in the Genpei Jōsuiki (源平盛哀記) in relation to an 1180 war in Kotsubo between the Miura clan and the Hatakeyama clan is indeed the Shakadō Pass.[47] In any case, the presence of two yagura tombs within it means that it can be dated to at least the Kamakura period. It was then an important way of transit, but it was also much narrower than today and harder to pass.[47]

Inside the pass, there are two small yagura tombs containing some gorintō. On the Shakadōgayatsu side of the pass, just before the first houses a small street on the left takes to a large group of yagura called Shakadōgayatsu Yagura-gun.[47] There rest the bones of some of the hundreds of Hōjō family members who committed suicide at Tōshō-ji after the fall of Kamakura in 1333.[47]

The pass appears many times in some recent Japanese films like "The Blue Light", Tada, Kimi o Aishiteru, and 'Peeping Tom' (真木栗ノ穴, Makiguri no ana). The pass is presently closed to all traffic because of the danger posed by falling rocks.

On April 28, 2010, a day of heavy rain, a large section of rock on the Omachi side of the Shakado Pass gave way, making the road temporarily impassable for pedestrians.

Yagura tombs

An important and characteristic feature of Kamakura is a type of grave called yagura (やぐら).[48] Yagura are caves dug on the side of hills during the Middle Ages to serve as tombs for high-ranking personalities and priests.[48] Two famous examples are Hōjō Masako's and Minamoto no Sanetomo's cenotaphs in Jufuku-ji's cemetery, about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) from Kamakura Station.

Usually present in the cemetery of most Buddhist temples in the town, they are extremely numerous also in the hills surrounding it, and estimates of their number always put them in the thousands.[48] Yagura can be found either isolated or in groups of even 180 graves, as in the Hyakuhachi Yagura (百八やぐら).[48] Many are now abandoned and in a bad state of preservation.[48]

The reason why they were dug is not known, but it is thought likely that the tradition started because of the lack of flat land within the narrow limits of Kamakura's territory. Started during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), the tradition seems to have declined during the following Muromachi period, when storehouses and cemeteries came to be preferred.

True yagura can be found also in the Miura Peninsula, in the Izu Peninsula, and even in distant Awa Province (Chiba).[48]

Tombs in caves can also be found in the Tōhoku region, near Hiroshima and Kyoto, and in Ishikawa Prefecture, however they are not called yagura and their relationship with those in Kanagawa Prefecture is unknown.

Transportation

Rail

JR East's Yokosuka Line has three stations within the city. Ōfuna Station is the northernmost. Next is Kita-Kamakura Station. In the center of the city is Kamakura Station, the central railway station in the city.

Kamakura Station is the terminal for the Enoshima Electric Railway. This railway runs westward to Fujisawa, and part of its route runs parallel to the seashore. After leaving Kamakura Station, trains make eight more station stops in the city. One of them is Hase Station, closest to Hase-dera and Kōtoku-in. The next station on the line is Gokurakuji Station, one of the settings for the 2014 film Our Little Sister.

Highway

Education

Kamakura has many educational facilities. The city operates sixteen public elementary schools and nine middle schools. The national government has one elementary and one middle school, and there are two private elementary and six private middle schools. At the next level are four prefectural and six private high schools. Also in Kamakura is a prefectural special school.

Kamakura Women's University is the city's sole university.

Government and administration

Kamakura has a mayor and a city council, all publicly elected. The mayor is Takashi Matsuo.[49] The City Council consists of 28 members.

Sister cities

Kamakura has six sister cities. Three are in Japan and three are overseas:[50]

- Nice, France (1966)[51]

- Ueda, Nagano, Japan (1979)

- Hagi, Yamaguchi, Japan (1979)

- Ashikaga, Tochigi, Japan (1982)

- Dunhuang, China (1998)

- Nashville, Tennessee, USA (2014)

loge

Kamakura has many historical houses. Tukikagetei is one of the famous houses. It had constructed 100 years ago in the Taisho era. But now, Fukagawa Geisha uses this house for their lives.

Notes

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Hiking to Kamakura's Seven Entrances and Seven Passes, The Kamakura Citizen Net (in Japanese)

- 1 2 3 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 64)

- 1 2 Ōnuki (2008:50)

- ↑ Yume Kōbō (2008:4)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 56–57)

- ↑ Kamakura population statistics (from city website, in Japanese)

- ↑ Kamakura population statistics (1995-2020)

- 1 2 Kamakura: History and the Historic Sites – Through the Heian Period, the Kamakura Citizen Net, retrieved on April 27, 2008

- 1 2 Takahashi (2005:8–10)

- 1 2 3 Kamakura: History & Historic Sites – Origin of the Name Kamakura, the Kamakura Citizen Net, retrieved on April 27, 2008

- ↑ Kurano (1958: 224–225)

- ↑ Satake (2002: 315, 337)

- ↑ Satake (2003: 393)

- ↑ Minamoto (1966, 203–204)

- ↑ 「『鎌倉』と鎌足」 ("Kamakura" and Kamatari), 黒田智 (Kuroda, Satoshi). In Japanese. Paper in Kamakura Ibun Kenkyū, Vol. 3; Tōkyō-dō Shuppan, 2002; ISBN 978-4-490-20469-8

- ↑ Weapons & Fighting Techniques Of The Samurai Warrior 1200–1877 AD. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Takahashi (2005:2)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kamakura: History & Historic Sites – The Kamakura Period, the Kamakura Citizen Net, retrieved on April 27, 2008

- ↑ See article Tomb of Minamoto no Yoritomo

- ↑ Cities, Empires and Global State Formation. Institute for Research on World-Systems

- ↑ Gregorian date obtained directly from the original Nengō (Genkō 3, 21st day of the 5th month) using Nengocalc Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mutsu (1995/06: 19–40)

- 1 2 Matsuo (1997:V-VI)

- 1 2 3 Papinot (1906:247–248)

- 1 2 Sansom (1977:22)

- 1 2 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008:24–25)

- 1 2 3 4 Kokushi Daijiten (1983:542)

- ↑ Jansen (1995:119–120)

- ↑ Matsuo (1997:119–120)

- ↑ Papinot (1972:247)

- 1 2 3 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 28)

- ↑ See article Jufuku-ji

- ↑ See article Meigetsu-in

- ↑ Hammer (2006: 278)

- ↑ Hammer (2006: 115–116).

- ↑ Hammer (2006:116)

- ↑ Kamakura: History and the Historic Sites – Kamakura in the Modern era (the Meiji period) and following sections, The Kamakura Citizen net, retrieved on April 5, 2008]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mutsu (1995/06: 258–271)

- 1 2 The ending "ヶ谷", common in place names and usually read "-gaya", in Kamakura is normally pronounced "-gayatsu", as in Shakadōgayatsu, Ōgigayatsu, and Matsubagayatsu.

- ↑ Shakyamuni Buddha and His Supporters, Nichirenshu.org, retrieved on May 25, 2008

- ↑ Photo of Hosshō-ji's gate with its sculpted white monkeys

- 1 2 3 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 46)

- ↑ Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 186)

- ↑ See also Ofuna Kannonji Temple Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 170–188)

- 1 2 3 Kamakura City's List of Festivals and Events

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kamiya Vol. 1 (2006/08: 71 – 72)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008: 35 – 36)

- ↑ "鎌倉市長のページ / 鎌倉市". Archived from the original on 2008-04-05. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Introduction to Kamakura かまくら GreenNet Archived 2008-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Villes jumelées avec la Ville de Nice" (in French). Ville de Nice. Archived from the original on October 29, 2012. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

General and cited references

- Hall, John Whitney, Peter Duus (1990). Yamamura Kozo (ed.). The Cambridge History of Japan (Hardcover ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22354-6.

- Hammer, Joshua (2006). Yokohama Burning: The Deadly 1923 Earthquake and Fire that Helped Forge the Path to World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6465-5 (cloth)

- Harada, Hiroshi (2007). Kamakura no Koji (in Japanese). JTB Publishing. ISBN 978-4-533-07104-1.

- Jansen, Marius (1995). Warrior Rule in Japan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521482394 OCLC 31515317

- Kamakura City's List of Festivals and Events (in Japanese)

- Kamakura Shōkō Kaigijo (2008). Kamakura Kankō Bunka Kentei Kōshiki Tekisutobukku (in Japanese). Kamakura: Kamakura Shunshūsha. ISBN 978-4-7740-0386-3.

- Kamakura Today: Annual Events (in English)

- Kamiya, Michinori (August 2000). Fukaku Aruku – Kamakura Shiseki Sansaku Vol. 1 (in Japanese). Kamakura: Kamakura Shunshūsha. ISBN 4-7740-0340-9.

- Kita-Kamakura Yūsui Network (2008). Gaidobukku ni Noranai Kita-Kamakura (in Japanese). Yume Kōbō. ISBN 978-4-86158-026-0.

- Kokushi Daijiten Iinkai. Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Vol. 3 (1983 ed.).

- Kurano, Kenji; Yūkichi Takeda (1958). Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei 1: Kojiki. Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-060001-X.

- Matsu, Ri (2012). Everyday Kamakura. DigitalKu. ISBN 978-1-4700-3285-2.

- Matsuo, Kenji (1997). Chūsei Toshi Kamakura wo Aruku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Chūkō Shinsho. ISBN 4-12-101392-1.

- Minamoto, Shitagō (1966). Kyōto Daigaku Bungakubu Kokugogaku Kokubungaku Kenkyūshitu (ed.). Shohon Shūsei Wamyō Ruijushō: Gaihen. Kyōto: Rinsen. ISBN 4-653-00508-7.

- Mutsu, Iso (June 1995). Kamakura: Fact and Legend. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-1968-8.

- Ōnuki, Akihiko (2008). Kamakura. Rekishi to Fushigi wo Aruku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Jitsugyō no Nihonsha. ISBN 978-4-408-59306-7.

- Papinot, Edmond (1910). Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan (Japanese ed.). Tuttle. ISBN 0-8048-0996-8.

- Sansom, George Bailey (January 1, 1977). A History of Japan (3-volume boxed set). Vol. 2 (2000 ed.). Charles E. Tuttle Co. ISBN 4-8053-0375-1.

- Satake, Akihiro; Hideo Yamada; Rikio Kudō; Masao Ōtani; Yoshiyuki Yamazaki (2002). Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man'yōshū 3 (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-240003-4.

- Satake, Akihiro; Hideo Yamada; Rikio Kudō; Masao Ōtani; Yoshiyuki Yamazaki (2003). Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man'yōshū 4 (in Japanese). Tōkyō: Iwanami Shoten. ISBN 4-00-240004-2.

- Takahashi, Shin'ichirō (2005). Buke no koto, Kamakura (in Japanese). Tokyo: Yamakawa Shuppansha. ISBN 4-634-54210-2.

External links

- Official Website (in Japanese)

- Kanagawa Official Tourism Website (in English)

Geographic data related to Kamakura at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Kamakura at OpenStreetMap