| Greenlandic | |

|---|---|

| kalaallisut | |

Sign in Greenlandic and Danish | |

| Native to | Greenland |

| Region | Greenland, Denmark |

| Ethnicity | Greenlandic Inuit |

Native speakers | 57,000 (2007)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Oqaasileriffik |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | kl |

| ISO 639-2 | kal |

| ISO 639-3 | kal |

| Glottolog | gree1280 |

| ELP | Kalaallisut |

| IETF | kl |

West Greenlandic is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Greenlandic (Greenlandic: kalaallisut [kalaːɬːisʉt]; Danish: grønlandsk [ˈkʁɶnˌlænˀsk]) is an Eskimo–Aleut language with about 57,000 speakers,[1] mostly Greenlandic Inuit in Greenland. It is closely related to the Inuit languages in Canada such as Inuktitut. It is the most widely spoken Eskimo–Aleut language. In June 2009, the government of Greenland, the Naalakkersuisut, made Greenlandic the sole official language of the autonomous territory, to strengthen it in the face of competition from the colonial language, Danish. The main variety is Kalaallisut, or West Greenlandic. The second variety is Tunumiit oraasiat, or East Greenlandic. The language of the Inughuit (Thule Inuit) of Greenland, Inuktun or Polar Eskimo, is a recent arrival and a dialect of Inuktitut.

Greenlandic is a polysynthetic language that allows the creation of long words by stringing together roots and suffixes. The language's morphosyntactic alignment is ergative, treating both the argument (subject) of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb in one way, but the subject of a transitive verb in another. For example, "he plays the guitar" would be in the ergative case as a transitive agent, whereas "I bought a guitar" and "as the guitar plays" (the latter being the intransitive sense of the same verb "to play") would both be in the absolutive case.

Nouns are inflected by one of eight cases and for possession. Verbs are inflected for one of eight moods and for the number and person of its subject and object. Both nouns and verbs have complex derivational morphology. The basic word order in transitive clauses is subject–object–verb. The subordination of clauses uses special subordinate moods. A so-called fourth-person category enables switch-reference between main clauses and subordinate clauses with different subjects. Greenlandic is notable for its lack of grammatical tense; temporal relations are expressed normally by context but also by the use of temporal particles such as "yesterday" or "now" or sometimes by the use of derivational suffixes or the combination of affixes with aspectual meanings with the semantic lexical aspect of different verbs. However, some linguists have suggested that Greenlandic always marks future tense. Another question is whether the language has noun incorporation or whether the processes that create complex predicates that include nominal roots are derivational in nature.

When adopting new concepts or technologies, Greenlandic usually constructs new words made from Greenlandic roots, but modern Greenlandic has also taken many loans from Danish and English. The language has been written in Latin script since Danish colonization began in the 1700s. Greenlandic's first orthography was developed by Samuel Kleinschmidt in 1851, but within 100 years, it already differed substantially from the spoken language because of a number of sound changes. An extensive orthographic reform was undertaken in 1973 and made the script much easier to learn. This resulted in a boost in Greenlandic literacy, which is now among the highest in the world.[lower-alpha 1][5]

History

Greenlandic was brought to Greenland by the arrival of the Thule people in the 1200s. The languages that were spoken by the earlier Saqqaq and Dorset cultures in Greenland are unknown.

The first descriptions of Greenlandic date from the 1600s. With the arrival of Danish missionaries in the early 1700s and the beginning of Danish colonization of Greenland, the compilation of dictionaries and description of grammar began. The missionary Paul Egede wrote the first Greenlandic dictionary in 1750 and the first grammar in 1760.[6]

From the Danish colonization in the 1700s to the beginning of Greenlandic home rule in 1979, Greenlandic experienced increasing pressure from the Danish language. In the 1950s, Denmark's linguistic policies were directed at strengthening Danish. Of primary significance was the fact that post-primary education and official functions were conducted in Danish.[7]

From 1851 to 1973, Greenlandic was written in a complicated orthography devised by the missionary linguist Samuel Kleinschmidt. In 1973, a new orthography was introduced, intended to bring the written language closer to the spoken standard, which had changed considerably since Kleinschmidt's time. The reform was effective, and in the years following it, Greenlandic literacy has received a boost.[7]

Another development that has strengthened Greenlandic language is the policy of "Greenlandization" of Greenlandic society that began with the home rule agreement of 1979. The policy has worked to reverse the former trend towards marginalization of the Greenlandic language by making it the official language of education. The fact that Greenlandic has become the only language used in primary schooling means that monolingual Danish-speaking parents in Greenland are now raising children bilingual in Danish and Greenlandic.[8] Greenlandic now has several dedicated news media: the Greenlandic National Radio, Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa, which provides television and radio programming in Greenlandic. The newspaper Sermitsiaq has been published since 1958 and merged in 2010 with the other newspaper Atuagagdliutit/Grønlandsposten, which had been established in 1861 to form a single large Greenlandic language publishing house.[9][10]

Before June 2009, Greenlandic shared its status as the official language in Greenland with Danish.[lower-alpha 2] Since then, Greenlandic has become the sole official language.[2] That has made Greenlandic a unique example of an indigenous language of the Americas that is recognized by law as the only official language of a semi-independent country. Nevertheless, it is still considered to be in a "vulnerable" state by the UNESCO Red Book of Language Endangerment.[12] The country has a 100% literacy rate.[13] As the Western Greenlandic standard has become dominant, a UNESCO report has labelled the other dialects as endangered, and measures are now being considered to protect the Eastern Greenlandic dialect.[14]

Classification

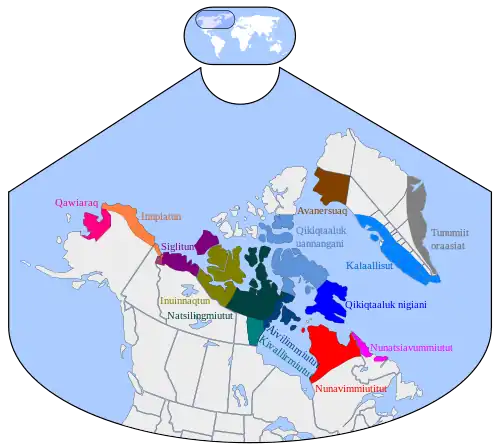

Kalaallisut and the other Greenlandic dialects belong to the Eskimo–Aleut family and are closely related to the Inuit languages of Canada and Alaska. Illustration 1 shows the locations of the different Inuit languages, among them the two main dialects of Greenlandic and the separate language Inuktun ("Avanersuaq").

| English | Kalaallisut | Inuktun | Tunumiisut |

|---|---|---|---|

| humans | inuit | inughuit[15] | iivit[16] |

The most prominent Greenlandic dialect is Kalaallisut, which is the official language of Greenland. The name Kalaallisut is often used as a cover term for all of Greenlandic. The eastern dialect (Tunumiit oraasiat), spoken in the vicinity of Ammassalik Island and Ittoqqortoormiit, is the most innovative of the Greenlandic dialects since it has assimilated consonant clusters and vowel sequences more than West Greenlandic.[17]

Kalaallisut is further divided into four subdialects. One that is spoken around Upernavik has certain similarities to East Greenlandic, possibly because of a previous migration from eastern Greenland. A second dialect is spoken in the region of Uummannaq and the Disko Bay. The standard language is based on the central Kalaallisut dialect spoken in Sisimiut in the north, around Nuuk and as far south as Maniitsoq. Southern Kalaallisut is spoken around Narsaq and Qaqortoq in the south.[6] Table 1 shows the differences in the pronunciation of the word for "humans" in the two main dialects and Inuktun. It can be seen that Inuktun is the most conservative by maintaining ⟨gh⟩, which has been elided in Kalaallisut, and Tunumiisut is the most innovative by further simplifying its structure by eliding /n/.

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i (y) | (ʉ) | u |

| Mid | (e~ɛ~ɐ) | (o~ɔ) | |

| Open | a | (ɑ) | |

The Greenlandic three-vowel system, composed of /i/, /u/, and /a/, is typical for an Eskimo–Aleut language. Double vowels are analyzed as two morae and so they are phonologically a vowel sequence and not a long vowel. They are also orthographically written as two vowels.[19][20] There is only one diphthong, /ai/, which occurs only at the ends of words.[21] Before a uvular consonant (/q/ or /ʁ/), /i/ is realized allophonically as [e], [ɛ] or [ɐ], and /u/ is realized allophonically as [o] or [ɔ], and the two vowels are written ⟨e, o⟩ respectively (as in some orthographies used for Quechua and Aymara).[22] /a/ becomes retracted to [ɑ] in the same environment. /i/ is rounded to [y] before labial consonants.[22] /u/ is fronted to [ʉ] between two coronal consonants.[22]

The allophonic lowering of /i/ and /u/ before uvular consonants is shown in the modern orthography by writing /i/ and /u/ as ⟨e⟩ and ⟨o⟩ respectively before ⟨q⟩ and ⟨r⟩. For example:

- /ui/ "husband" pronounced [ui].

- /uiqarpuq/ "(s)he has a husband" pronounced [ueqɑppɔq] and written ⟨ueqarpoq⟩.

- /illu/ "house" pronounced [iɬɬu].

- /illuqarpuq/ "(s)he has a house" pronounced [iɬɬoqɑppɔq] and written ⟨illoqarpoq⟩.

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | |||||

| Nasals | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ɴ ⟨rn⟩[lower-alpha 3] | ||

| Plosives | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | q ⟨q⟩ | ||

| Affricate | t͡s[lower-alpha 4] | |||||

| Fricatives | v ⟨v⟩[lower-alpha 5] | s ⟨s⟩ | ɬ ⟨ll⟩[lower-alpha 6] | ʃ[lower-alpha 7] | ɣ ⟨g⟩ | ʁ ⟨r⟩ |

| Liquids | l ⟨l⟩ | |||||

| Semivowel | j ⟨j⟩ | |||||

The palatal sibilant [ʃ] has merged with [s] in all dialects except those of the Sisimiut–Maniitsoq–Nuuk–Paamiut area.[23][24] The labiodental fricative [f] is contrastive only in loanwords. The alveolar stop /t/ is pronounced as an affricate [t͡s] before the high front vowel /i/. Often, Danish loanwords containing ⟨b d g⟩ preserve these in writing, but that does not imply a change in pronunciation, for example ⟨baaja⟩ [paːja] "beer" and ⟨Guuti⟩ [kuːtˢi] "God"; these are pronounced exactly as /p t k/.[25]

Grammar

Morphology

The broad outline of the Greenlandic grammar is similar to other Eskimo languages, on the morpholological and syntactic plan.

The morphology of Greenlandic is highly synthetic and exclusively suffixing[26] (except for a single highly-limited and fossilized demonstrative prefix). The language creates very long words by means of adding strings of suffixes to a stem.[lower-alpha 8] In principle, there is no limit to the length of a Greenlandic word, but in practice, words with more than six derivational suffixes are not so frequent, and the average number of morphemes per word is three to five.[27][lower-alpha 9] The language has between 400 and 500 derivational suffixes and around 318 inflectional suffixes.[28]

There are few compound words but many derivations.[29] The grammar uses a mixture of head and dependent marking. Both agent and patient are marked on the predicate, and the possessor is marked on nouns, with dependent noun phrases inflecting for case. The primary morphosyntactic alignment of full noun phrases in Kalaallisut is ergative-absolutive, but verbal morphology follows a nominative-accusative pattern and pronouns are syntactically neutral.

The language distinguishes four persons (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th or 3rd reflexive (see Obviation and switch-reference); two numbers (singular and plural but no dual, unlike Inuktitut); eight moods (indicative, interrogative, imperative, optative, conditional, causative, contemporative and participial) and eight cases (absolutive, ergative, equative, instrumental, locative, allative, ablative and prolative). Greenlandic (as well as the eastern minority's Tunumisut) is the only Eskimo language having lost its dual.

Declension

| Case | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutive | +∅ | +t |

| Ergative | +p | |

| Instrumental | +mik | +nik |

| Allative | +mut | +nut |

| Ablative | +mit | +nit |

| Locative | +mi | +ni |

| Prolative | +kkut | +tigut |

| Equative | +tut | |

Verbs carry a bipersonal inflection for subject and object. Possessive noun phrases inflect for both possessor and case.[30]

In this section, the examples are written in Greenlandic standard orthography except that morpheme boundaries are indicated by a hyphen.

Syntax

Greenlandic distinguishes three open word classes: nouns, verbs and particles. Verbs inflect for person and number of subject and object as well as for mood. Nouns inflect for possession and for case. Particles do not inflect.[31]

| Verb | Noun | Particle | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word | Oqar-poq say-3SG/IND "he says" |

Angut man.ABS "A man" |

Naamik No "No" |

The verb is the only word that is required in a sentence. Since verbs inflect for number and person of both subject and object, the verb is in fact a clause itself. Therefore, clauses in which all participants are expressed as free-standing noun phrases are rather rare.[31] The following examples show the possibilities of leaving out the verbal arguments:

Sini-ppoq

sleep-3SG/IND

"(S)he sleeps"

Angut

man.ABS

sinippoq

sleep-3SG/IND

"the man sleeps"

Asa-vaa

love-3SG/3SG

"(S)he loves him/her/it"

Angut-ip

man-ERG

asa-vaa

love-3SG/3SG

"the man loves him/her/it"

Arnaq

woman.ABS

asa-vaa

love-3SG/3SG

"(S)he loves the woman"

Morphosyntactic alignment

The Greenlandic language uses case to express grammatical relations between participants in a sentence. Nouns are inflected with one of the two core cases or one of the six oblique cases.[32]

Greenlandic is an ergative–absolutive language and so instead of treating the grammatical relations, as in English and most other Indo-European languages, whose grammatical subjects are marked with the nominative case and objects with the accusative case, Greenlandic grammatical roles are defined differently. Its ergative case is used for agents of transitive verbs and for possessors. The absolutive case is used for patients of transitive verbs and subjects of intransitive verbs.[33] Research into Greenlandic as used by the younger generation has shown that the use of ergative alignment in Kalaallisut may be becoming obsolete, which would convert the language into a nominative–accusative language.[34]

Anda

Anda.ABS

sini-ppoq

sleep-3SG/IND

"Anda sleeps"

Anda-p

Anda-ERG

nanoq

bear.ABS

taku-aa

see-3SG/3SG

"Anda sees a bear"

Word order

In transitive clauses whose object and subject are expressed as free noun phrases, the basic pragmatically-neutral word order is SOV / SOXV in which X is a noun phrase in one of the oblique cases. However, word order is fairly free. Topical noun phrases occur at the beginning of a clause. New or emphasized information generally come last, which is usually the verb but can also be a focal subject or object. As well, in the spoken language, "afterthought" material or clarifications may follow the verb, usually in a lowered pitch.[35]

On the other hand, the noun phrase is characterized by a rigid order in which the head of the phrase precedes any modifiers and the possessor precedes the possessed.[36]

In copula clauses, the word order is usually subject-copula-complement.

Andap

Anda

A

tujuuluk

sweater

O

pisiaraa

bought

V

"Anda bought the sweater"

An attribute appears after its head noun.

Andap

Anda

A

tujuuluk

sweater

O

tungujortoq

blue

X

pisiaraa

bought

V

"Anda bought the blue sweater"

An attribute of an incorporated noun appears after the verb:

Anda

Anda

S

sanasuuvoq

carpenter-is

V

pikkorissoq

skilled

APP

"Anda is a skilled carpenter"

Coordination and subordination

Syntactic coordination and subordination is built by combining predicates in the superordinate moods (indicative, interrogative, imperative and optative) with predicates in the subordinate moods (conditional, causative, contemporative and participial). The contemporative has both coordinative and subordinative functions, depending on the context.[37] The relative order of the main clause and its coordinate or subordinate clauses is relatively free and is subject mostly to pragmatic concerns.[38]

Obviation and switch-reference

The Greenlandic pronominal system includes a distinction known as obviation[39] or switch-reference.[40] There is a special so-called fourth person[41] to denote a third person subject of a subordinate verb or the possessor of a noun that is coreferent with the third person subject of the matrix clause.[42] Here are examples of the difference between third and the fourth persons:

third person fourth person illu-a

house-3.POSS

taku-aa

see-3SG/3SG

"he saw his (the other man's) house"

illu-ni

house-4.POSS

taku-aa

see-3SG/3SG

"he saw his own house"

Ole

Ole

oqar-poq

say-3SG

tillu-kkiga

hit-1SG/3SG

"Ole said I had hit him (the other man)"

Ole

Ole

oqar-poq

say-3SG

tillu-kkini

hit-1SG/4

"Ole said I had hit him (Ole)"

Eva

Eva

iser-pat

come in-3SG

sini-ssaa-q

sleep-expect-3SG

"When Eva comes in (s)he'll sleep (someone else)"

Eva

Eva

iser-uni

come in-4

sini-ssaa-q

sleep-expect-3SG

"When Eva comes in she'll sleep"

Indefiniteness construction

There is no category of definiteness in Greenlandic and so information on whether participants are already known to the listener or they are new to the discourse is encoded by other means. According to some authors, morphology related to transitivity such as the use of the construction sometimes called antipassive[43][44] or intransitive object[45] conveys such meaning, along with strategies of noun incorporation of non-topical noun phrases.[46][47] That view, however, is controversial.[48]

Piitap

Peter-ERG

arfeq

whale

takuaa

see

"Peter saw the whale"

Piitaq

Peter-ABS

arfermik

whale-INSTR

takuvoq

see

"Peter saw (a) whale"

Verbs

The morphology of Greenlandic verbs is enormously complex. The main processes are inflection and derivation. Inflectional morphology includes the processes of obligatory inflection for mood, person and voice (tense and aspect are not inflectional categories in Kalaallisut).[49][50][51] Derivational morphology modifies the meaning of verbs similarly to English adverbs. There are hundreds of such derivational suffixes. Many of them are so semantically salient and so they are often referred to as postbases, rather than suffixes, particularly in the American tradition of Eskimo grammar.[52] Such semantically "heavy" suffixes may express concepts such as "to have", "to be", "to say" or "to think". The Greenlandic verb word consists of a root, followed by derivational suffixes/postbases and then inflectional suffixes. Tense and aspect are marked by optional suffixes between the derivational and the inflectional suffixes.

Inflection

Greenlandic verbs inflect for agreement with agent and patient and for mood and for voice. There are eight moods, four of which are used in independent clauses the others in subordinate clauses. The four independent moods are indicative, interrogative, imperative and optative. The four dependent moods are causative, conditional, contemporative and participial. Verbal roots can take transitive, intransitive or negative inflections and so all eight mood suffixes have those three forms.[53] The inflectional system is even more complex since transitive suffixes encode both agent and patient in a single morpheme, with up to 48 different suffixes covering all possible combinations of agent and patient for each of the eight transitive paradigms. As some moods do not have forms for all persons (imperative has only 2nd person, optative has only 1st and 3rd person, participial mood has no 4th person and contemporative has no 3rd person), the total number of verbal inflectional suffixes is about 318.[54]

Indicative and interrogative moods

The indicative mood is used in all independent expository clauses. The interrogative mood is used for questions that do not have the question particle immaqa "maybe".[55]

napparsima-vit?

be sick-2/INTERR

"Are you sick?"

naamik,

no,

napparsima-nngila-nga

be sick-NEG-1/IND

"No, I am not sick"

The table below shows the intransitive inflection of the verb neri- "to eat" in the indicative and interrogative moods (question marks mark interrogative intonation; questions have falling intonation on the last syllable, unlike English and most other Indo-European languages, whose questions are marked by rising intonation). Both the indicative and the interrogative mood have a transitive and an intransitive inflection, but only the intransitive inflection is given here. Consonant gradation like in Finnish appears to occur in the verb conjugation (with strengthening to pp in the 3rd person plural and weakening to v elsewhere).

| indicative | interrogative |

|---|---|

| nerivunga "I am eating" | nerivunga? "Am I eating?" |

| nerivutit "You are eating" | nerivit? "Are you eating?" |

| nerivoq "He/she/it eats" | neriva? "Is he/she/it eating?" |

| nerivugut "We are eating" | nerivugut? "Are we eating?" |

| nerivusi "You are eating (pl.)" | nerivisi? "Are you eating? (pl.)" |

| neripput "They are eating" | nerippat? "Are they eating?" |

The table below shows the transitive indicative inflection for 1st, 2nd, and 3rd person singular subjects of the verb asa- "to love" (an asterisk means that the form does not occur as such but uses a different reflexive inflection).

| First person singular subject | Second person singular subject | Third person singular subject |

|---|---|---|

| * | asavarma love-2SG/1SG "You love me" |

asavaanga love-3SG/1SG "He/she/it loves me" |

asavakkit love-1SG/2SG "I love you" |

* | asavaatit love-3SG/2SG "He/she/it loves you" |

asavara love-1SG/3SG "I love him/her/it" |

asavat love-2SG/3SG "You love her/him/it" |

asavaa love-3SG/3SG "He/she/it loves him/her/it" |

| * | asavatsigut love-2SG/1PL "You love us" |

asavaatigut love-3SG/1PL "He/she/it loves us" |

asavassi love-1SG/2PL "I love you (pl.)" |

* | asavaasi love-3SG/2PL "He/she/it loves you (pl.)" |

asavakka love-1SG/3PL "I love them" |

asavatit love-2SG/3PL "You love them" |

asavai love-3SG/3PL "He/she/it loves them" |

The table below gives the basic form of all the inflexional suffixes in the indicative and interrogative moods. Where the indicative and interrogative forms differ, the interrogative form is given second in brackets. Suffixes used with intransitive verbs are in italics, while suffixes used with transitive verbs are unmarked.

| Subject of transitive verb | Object of transitive verb or subject of intransitive verb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | 2nd person singular | 3rd person singular | 1st person plural | 2nd person plural | 3rd person plural | ||

| vunga | vutit [vit?] | voq [va?] | vugut | vusi [visi?] | pput [ppat?] | ||

| 1st person | Singular | vakkit | vara | vassi | vakka | ||

| Plural | vatsigit | varput | vavut | ||||

| 2nd person | Singular | varma [vinga?] | vat [viuk?] | vatsigut [visigut?] | vatit [vigit?] | ||

| Plural | vassinga [visinga?] | varsi [visiuk?] | vasi [visigit?] | ||||

| 3rd person | Singular | vaanga | vaatit | vaa | vaatigut | vaasi | vai |

| Plural | vaannga | vaatsit | vaat | vaat | |||

Apart from the similarities between forms highlighted in bold, it will be observed that all basic forms start with v- except for the 3rd person plural intransitive forms, that all basic transitive indicative forms have /a/ as their first vowel, that all basic intransitive indicative forms have /u/ as their first vowel (voq is phonemically /vuq/), and that all basic forms unique to the interrogative mood have /i/ as their first vowel except for the 3rd person intransitive forms. Furthermore, if the subject of a transitive verb is 3rd person, the suffix will start with vaa- (with one exception). In the forms unique to the interrogative transitive (which all have 2nd person subjects), the forms with a (2nd person) singular subject are turned into forms with a (2nd person) plural subject by adding -si- after the initial vi- (except when the object is 1st person plural, in which case the same form is used for both plural and singular subject, as is the case for all indicative and interrogative forms with the object in the 1st or 2nd person plural). When the object is 1st or 2nd person singular, the forms with a 3rd person singular subject are turned into forms with a (3rd person) plural subject by lengthening the second consonant: [vaːŋa] → [vaːŋŋa], [vaːt͡sit̚] → [vaːtt͡sit̚]. If the subject or object is 2nd person plural, the suffix will include -si(-). If the subject or object is 1st person plural, the suffix will end in -t except when the object is 2nd person plural.

The interrogative mood has separate forms only when the subject is 2nd person or intransitive 3rd person; otherwise, the interrogative forms are identical to the indicative forms. All suffixes that start with vi- have a subject in the 2nd person.

The initial v- changes to p- or is deleted according to the rules described above.

After the suffix -nngil- ‘not’, v- is deleted (while the pp- of the 3rd person plural intransitive forms is changed to l-) and a first vowel /u/ is changed to /a/ (e.g. suli+vugut ‘we work’ but suli-nngil+agut ‘we don't work’). The intransitive 2nd person does not have separate interrogative forms after -nngil-, hence e.g. suli+vutit ‘you (sg.) work’, suli-nngil+atit ‘you (sg.) don't work’, suli+vit? ‘do you (sg.) work?’, suli-nngil+atit? ‘don't you (sg.) work?’ (instead of the expected *suli-nngil+it?).

After the future suffix -ssa-, vu- and vo- (both /vu/) change to a-. (Va-, vi-, ppu-, and ppa- do not change.)

After the suffix -qa- ‘very’, vu-, vo-, va-, vi-, ppu-, and ppa- all change to a- (except when this would lead to aaa, in which case aaa is shortened to aa). -qa- + vai becomes qai, not *qaai. (In accordance with the rule, aau becomes aaju, hence -qa- + viuk becomes qaajuk, not *qaauk.) The suffix -qa- was historically -qi-.

Imperative and optative moods

The imperative mood is used to issue orders and is always combined with the second person. The optative is used to express wishes or exhortations and is never used with the second person. There is a negative imperative form used to issue prohibitions. Both optative and imperative have transitive and intransitive paradigms. There are two transitive positive imperative paradigms: a standard one and another that is considered rude and is used usually to address children.[56]

sini-git!

sleep-IMP

"Sleep!"

sini-llanga

sleep-1.OPT

"Let me sleep!"

sini-nnak!

sleep-NEG.IMP

"Don't sleep!"

Conditional mood

The conditional mood is used to construct subordinate clauses that mean "if" or "when".[57]

seqinner-pat

sunshine-COND

Eva

Eva

ani-ssaa-q

go out-expect/3SG

"If the sun shines, Eva will go out"

Causative mood

The causative mood (sometimes called the conjunctive) is used to construct subordinate clauses that mean "because", "since" or "when" and is also sometimes used to mean "that". The causative is used also in main clauses to imply some underlying cause.[58]

qasu-gami

be tired-CAU/3SG

innar-poq

go to bed-3SG

"He went to bed because he was tired"

matta-ttor-ama

blubber-eat-CAU/1SG

"I've eaten blubber (that's why I'm not hungry)"

ani-guit

go out-COND/2SG

eqqaama-ssa-vat

remember-FUT-IMP

teriannia-qar-mat

fox-are-CAUS

"If you go out, remember that there are foxes"

Contemporative mood

The contemporative mood is used to construct subordinate clauses with the meaning of simultaneity and is used only if the subject of the subordinate clause and of the main clause are identical. If they differ, the participial mood or the causative mood is used. The contemporative can also be used to form complement clauses for verbs of speaking or thinking.[59]

qasu-llunga

be tired-CONT.1SG

angerlar-punga

go.home-1SG

"Being tired, I went home"

98-inik

98-INSTR.PL

ukio-qar-luni

year-have-CONT.4.SG

toqu-voq

die-3SG

"Being 98 years old, he/she died", "he/she was 98 when he/she died"

Eva

Eva

oqar-poq

say-3SG

kami-it

boot-PL

akiler-lugit

pay-CONT.3PL

"Eva said she had paid for the boots"

Participial mood

The participial mood is used to construct a subordinate clause describing its subject in the state of carrying out an activity. It is used when the matrix clause and the subordinate clause have different subjects. It is often used in appositional phrases such as relative clauses.[60]

atuar-toq

read-PART/3SG

taku-ara

see-1SG/3SG

"I saw her read/I saw that she read"

neriu-ppunga

hope-1SG

tiki-ssa-soq

come-expect-PART/3SG

"I hope he is coming/I hope he'll come"

Derivation

Verbal derivation is extremely productive, and Greenlandic has many hundreds of derivational suffixes. Often, a single verb uses more than one derivational suffix, resulting in very long words. Here are some examples of how derivational suffixes can change the meaning of verbs:

-katak- "be tired of" |

taku-katap-para see-tired.of-1SG/3SG "I am tired of seeing it/him/her |

|---|---|

-ler- "begin to/be about to" |

neri-ler-pugut eat-begin-1PL "We are about to eat" |

-llaqqik- "be proficient at" |

erinar-su-llaqqip-poq sing-HAB-proficiently-3SG She is good at singing |

-niar- "plans to/wants to" |

aallar-niar-poq travel-plan-3SG "He plans to travel" angerlar-niar-aluar-punga go.home-plan-though-1SG "I was planning to go home though" |

-ngajak- "almost" |

sini-ngajap-punga sleep-almost-1SG "I had almost fallen asleep" |

-nikuu-nngila- "has never" |

taku-nikuu-nngila-ra see-never-NEG-1SG/3SG "I have never seen it" |

-nngitsoor- "not anyway/afterall" |

tiki-nngitsoor-poq arrive-not.afterall-3SG "He hasn't arrived after all" |

Time reference and aspect

Greenlandic grammar has morphological devices to mark a distinction between the recent and distant past, but their use is optional[61] and so they should be understood as parts of Greenlandic's extensive derivational system, rather than as a system of tense-markers. Rather than by morphological marking, fixed temporal distance is expressed by temporal adverbials:[62]

All other things being equal and in the absence of any explicit adverbials, the indicative mood is interpreted as complete or incomplete, depending on the verbal lexical aspect.[64]

However, if a sentence with an atelic verbal phrase is embedded within the context of a past-time narrative, it would be interpreted as past.[65]

Greenlandic has several purely-derivational devices of expressing meaning related to aspect and lexical aspect such as sar, expressing "habituality", and ssaar, expressing, "stop to".[66] Also, there are at least two major perfect markers: sima and nikuu. sima can occur in several positions with obviously-different functions.[67] The last position indicates evidential meaning, but that can be determined only if several suffixes are present.

With atelic verbs, there is a regular contrast between indirective evidentiality, marked by sima, and witnessed evidentiality, marked by nikuu.[69] Its evidential meaning causes the combination of first person and sima to be sometimes marked.[70]

qia-sima-voq

cry-sima-3sg/IND

"He cried (his eyes are swollen)"

In the written language[63] and more recently also in the spoken language, especially by younger speakers, sima and nikuu can be used together with adverbials to refer to a particular time in the past.[71] That is, they can arguably mark time reference but do not yet do so systematically.

Just as Greenlandic does not systematically mark past tense, the language also does not have a future tense. Rather, it employs three different strategies to express future meaning:

Ilimaga-ara

expect-1sg/3sg/IND

aasaq

summer

manna

this

Dudley

Dudley

qujanar-tor-si-ffigi-ssa-llugu

be.fun-cn-get.from-expect-CONT/3sg

"I expect to get some fun out of Dudley this summer."

Aggiuti-ler-para

bring-begin-1sg/3sg/IND

"I've started to bring him."

Qimmii-t

dog-PL

nerisi(k)-tigit

feed-please-we/them/IMP

"Let us feed the dogs, ok?"[73]

The status of the perfect markers as aspect is not very controversial, but some scholars have claimed that Greenlandic has a basic temporal distinction between future and nonfuture. Especially, the suffix -ssa and handful of other suffixes have been claimed to be obligatory future markers.[74][75] However, at least for literary Greenlandic, the suffixes have been shown to have other semantics, which can be used to refer to the future by the strategies that have just been described.[76]

Voice

Greenlandic has an antipassive voice, which transforms the ergative subject into an absolutive subject and the absolutive object into an instrumental argument; it is formed mostly by the addition of the marker -(s)i- to the verb (the presence of the consonant being mostly phonologically determined, albeit with a few cases of lexically determined distribution) and, in small lexically restricted sets of verbs, by the addition of -nnig- or -ller- (the former being, however, more frequent because it is the one selected by the common verbal element -gi/ri- 'to have as').[77] It has also been analysed as having passive voice constructions, which are formed with the elements -saa- (composed of the passive participle suffix -sa- and -u- 'to be'), -neqar- (composed of the verbal noun suffix -neq- and -qar- 'to have') and -tit- (only to demote higher animate participants, also used with a reflexive causative meaning 'to cause, let [someone do something to one]'). In addition, an "impersonal passive" from intransitive verbs -toqar- (composed of intransitive agent suffix -toq- and -qar 'to have') has been identified.[78]

Noun incorporation

There is also a debate in the linguistic literature on whether Greenlandic has noun incorporation. The language does not allow the kind of incorporation that common in many other languages in which a noun root can be incorporated into almost any verb to form a verb with a new meaning. On the other hand, Greenlandic often forms verbs that include noun roots. The question then becomes whether to analyse such verb formations as incorporation or as denominal derivation of verbs. Greenlandic has a number of morphemes that require a noun root as their host and form complex predicates, which correspond closely in meaning to what is often seen in languages that have canonical noun incorporation. Linguists who propose that Greenlandic had incorporation argue that such morphemes are in fact verbal roots, which must incorporate nouns to form grammatical clauses.[44][79][80][81][82][83] That argument is supported by the fact that many of the derivational morphemes that form denominal verbs work almost identically to canonical noun incorporation. They allow the formation of words with a semantic content that correspond to an entire English clause with verb, subject and object. Another argument is that the morphemes that derive denominal verbs come from historical noun incorporating constructions, which have become fossilized.[84]

Other linguists maintain that the morphemes in question are simply derivational morphemes that allow the formation of denominal verbs. That argument is supported by the fact that the morphemes are always latched on to a nominal element.[85][86][87] These examples illustrate how Greenlandic forms complex predicates including nominal roots:

qimmeq "dog" +

-qar- "have" |

qimme- dog -qar- have -poq 3SG "She has a dog" |

|---|---|

illu "house" +

-lior- "make" |

illu- house -lior- make -poq 3SG "She builds a house" |

kaffi "coffee" +

-sor- "drink/eat" |

kaffi- coffee -sor- drink/eat -poq 3SG "She drinks coffee" |

puisi "seal" +

-nniar- "hunt" |

puisi- seal -nniar- hunt -poq 3SG "She hunts seal" |

allagaq "letter" +

-si- "receive" |

allagar- letter -si- receive -voq 3SG "She has received a letter" |

anaana "mother" +

-a- "to be" |

anaana- mother -a- to be -voq 3SG "She is a mother" |

Nouns

Nouns are always inflected for case and number and sometimes for number and person of possessor. Singular and plural are distinguished and eight cases are used: absolutive, ergative (relative), instrumental, allative, locative, ablative, prosecutive (also called vialis or prolative) and equative.[88] Case and number are marked by a single suffix. Nouns can be derived from verbs or from other nouns by a number of suffixes: atuar- "to read" + -fik "place" becomes atuarfik "school" and atuarfik + -tsialak "something good" becomes atuarfitsialak "good school".

Since the possessive agreement suffixes on nouns and the transitive agreement suffixes on verbs in a number of instances have similar or identical shapes, there is even a theory that Greenlandic distinguishes between transitive and intransitive nouns as it does for verbs.[89][lower-alpha 10]

Pronouns

There are personal pronouns for first, second, and third person singular and plural. They are optional as subjects or objects but only when the verbal inflection refers to such arguments.[90]

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | uanga | uagut |

| 2nd person | illit | ilissi |

| 3rd person | una | uku |

Personal pronouns are, however, required in the oblique case:

illit

you

nere-qu-aatit

eat-tell to-3s–2s-IND

'He told you to eat'

Case

Both grammatical core cases, ergative and absolutive, are used to express grammatical and syntactical roles of participant noun phrases. The oblique cases express information related to movement and manner.

| case | singular | plural |

|---|---|---|

| Absolutive | -Ø | -(i)t |

| Ergative | -(u)p | -(i)t |

| Instrumental | -mik | -nik |

| Allative | -mut | -nut |

| Locative | -mi | -ni |

| Ablative | -mit | -nit |

| Prosecutive | -kkut | -tigut |

| Equative | -tut | -tut |

angut-Ø

man-ABS

neri-voq

eat-3sg

"The man eats"

anguti-p

man-ERG

puisi

seal-ABS

neri-vaa

eat-3sg/3sg

"The man eats the seal"

The instrumental case is versatile. It is used for the instrument with which an action is carried out, for oblique objects of intransitive verbs (also called antipassive verbs)[44][91][92] and for secondary objects of transitive verbs.[93]

nanoq-Ø

polar bear-ABS

savim-mi-nik

knife-his.own-INSTR

kapi-vaa

stab-3sg/3sg

"He stabbed the bear with his knife"

Piitaq-Ø

Peter-ABS

savim-mik

knife-INSTR

tuni-vara

give-1sg/3sg

"I gave Peter a knife"

There is no case marking if the noun is incorporated. Many sentences can be constructed oblique object as well as incorporated object.

kaffi-sor-tar-poq

coffee-drink-usually-3sg

"She usually drinks coffee"

kaffi-mik

coffee-INSTR

imer-tar-poq

drink-usually-3sg

"She usually drinks coffee"

It is also used to express the meaning of "give me" and to form adverbs from nouns:

imer-mik!

water-INSTR

"(give me) water"

sivisuu-mik

late-INSTR

sinip-poq

sleep-3sg

"He slept late"

The allative case describes movement towards something.[94]

illu-mut

house-ALL

"towards the house"

It is also used with numerals and the question word qassit to express the time of the clock and in the meaning "amount per unit":

qassi-nut?

when-ALL

–

pingasu-nut.

three-ALL

"When?" – "At three o'clock"

kiilu-mut

kilo-ALL

tiiva

twenty

krone-qar-poq

crown-have-3sg

"It costs 20 crowns per kilo"

The locative case describes spatial location:[94]

illu-mi

house-LOC

"in the house"

The ablative case describes movement away from something or the source of something:[94]

Rasmussi-mit

Rasmus-ABL

allagarsi-voq

receive.letter-3sg

"He got a letter from Rasmus"

The prosecutive case describes movement through something and the medium of writing or a location on the body.[95]

matu-kkut

door-PROS

iser-poq

enter-3SG

"He entered through the door"

su-kkut

where-PROS

tillup-paatit?

hit-3sg/2sg

"Where (on the body) did he hit you?"

The prosecutive case ending "-kkut" is distinct from the affix "-kkut" which denotes a noun and its companions, e.g. a person and friends or family([96]):

palasi-kkut

priest-and-companions-of

"the priest and his family"

The equative case describes similarity of manner or quality. It is also used to derive language names from nouns denoting nationalities: "like a person of x nationality [speaks]".[95]

nakorsatut

doctor-EQU

suli-sar-poq

work-HAB-3SG

"he works as a doctor"

Qallunaa-tut

dane-EQU

"Danish language (like a Dane)"

Possession

| Possessor | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | illora "my house" | illukka "my houses" |

| 2nd person singular | illut "your house" | illutit "your houses" |

| 3rd person singular | illua "his house" | illui "his houses" |

| 4th person singular | illuni "his own house" | illuni "his own houses" |

| 1st person plural | illorput "our house" | illuvut "our houses" |

| 2nd person plural | illorsi "your (pl) house" | illusi "your (pl) houses" |

| 3rd Person plural | illuat "their house" | illui "their houses" |

| 4th person plural | illortik "their own house" | illutik "their own houses" |

In Greenlandic, possession is marked on the noun that agrees with the person and the number of its possessor. The possessor is in the ergative case. There are different possessive paradigms for each different case.[97] Table 4 gives the possessive paradigm for the absolutive case of illu "house". Here are examples of the use of the possessive inflection, the use of the ergative case for possessors and the use of fourth person possessors.

Anda-p

Anda-ERG

illu-a

house-3SG/POSS

"Anda's house"

Anda-p

Anda-ERG

illu-ni

house-4/POSS

taku-aa

see-3SG/3SG

"Anda sees his own house"

Anda-p

Anda-ERG

illu-a

house-3SG/POSS

taku-aa

see-3SG/3SG

"Anda sees his (the other man's) house"

Numerals

The numerals and lower numbers are,[98]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ataaseq | marluk | pingasut | sisamat | tallimat | arfinillit |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| arfineq-marluk | arfineq-pingasut |

|

qulit |

|

|

Vocabulary

Most of Greenlandic's vocabulary is inherited from Proto-Eskimo–Aleut, but there are also a large number of loans from other languages, especially from Danish. Early loans from Danish have often become acculturated to the Greenlandic phonological system: the Greenlandic word palasi "priest" is a loan from the Danish præst. However, since Greenlandic has an enormous potential for the derivation of new words from existing roots, many modern concepts have Greenlandic names that have been invented rather than borrowed: qarasaasiaq "computer" which literally means "artificial brain". The potential for complex derivations also means that Greenlandic vocabulary is built on very few roots, which, combined with affixes, form large word families.[6] For example, the root for "tongue" oqaq is used to derive the following words:

- oqarpoq 'says'

- oqaaseq 'word'

- oqaluppoq 'speaks'

- oqallissaarut 'discussion paper'

- oqaasilerisoq 'linguist'

- oqaasilerissutit 'grammar'

- oqaluttualiortoq 'author'

- oqaloqatigiinneq 'conversation'

- oqaasipiluuppaa 'harangues him'

- oqaatiginerluppaa 'speaks badly about him'

Lexical differences between dialects are often considerable because of the earlier cultural practice of imposing a taboo on words that had served as names for a deceased person. Since people were often named after everyday objects, many of them have changed their name several times because of taboo rules, another cause of the divergence of dialectal vocabulary.[6]

Orthography

.JPG.webp)

Greenlandic is written with the Latin script. The alphabet consists of 18 letters:

- A E F G I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V

⟨b, c, d, h, w, x, y, z, æ, ø, å⟩ are used to spell loanwords, especially from Danish and English.[99][100] Greenlandic uses "..." and »...« as quotation marks.

From 1851 until 1973, Greenlandic was written in an alphabet invented by Samuel Kleinschmidt, which used the kra (⟨ĸ⟩, capitalised ⟨K’⟩) which was replaced by ⟨q⟩ in the 1973 reform.[101] In the Kleinschmidt alphabet, long vowels and geminate consonants were indicated by diacritics on vowels (in the case of consonant gemination, the diacritics were placed on the vowel preceding the affected consonant). For example, the name Kalaallit Nunaat was spelled Kalãlit Nunât or Kalàlit Nunât. This scheme uses the circumflex (◌̂) to indicate a long vowel (e.g. ⟨ât, ît, ût⟩; modern: ⟨aat, iit, uut⟩), an acute accent (◌́) to indicate gemination of the following consonant: (i.e. ⟨ák, ík, úk⟩; modern: ⟨akk, ikk, ukk⟩) and, finally, a tilde (◌̃) or a grave accent (◌̀), depending on the author, indicates vowel length and gemination of the following consonant (e.g. ⟨ãt/àt, ĩt/ìt, ũt/ùt⟩; modern: ⟨aatt, iitt, uutt⟩). ⟨ê, ô⟩, used only before ⟨r, q⟩, are now written ⟨ee, oo⟩ in Greenlandic. The spelling system of Nunatsiavummiutut, spoken in Nunatsiavut in northeastern Labrador, is derived from the old Greenlandic system.

Technically, the Kleinschmidt orthography focused upon morphology: the same derivational affix would be written in the same way in different contexts, despite its being pronounced differently in different contexts. The 1973 reform replaced this with a phonological system: Here, there was a clear link from written form to pronunciation, and the same suffix is now written differently in different contexts: for example ⟨e, o⟩ do not represent separate phonemes, but only more open pronunciations of /i/ /u/ before /q/ /ʁ/. The differences are due to phonological changes. It is therefore easy to go from the old orthography to the new (cf. the online converter)[102] whereas going the other direction would require a full lexical analysis.

Example text

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Greenlandic:

(Pre-reform)

- Inuit tamarmik inúngorput nangminêrsivnâgsusseĸarlutik agsigĩmigdlo atarĸinagsusseĸarlutigdlo pisivnâtitãfeĸarlutik. Silaĸagsussermik tarnigdlo nalúngigsussianik pilerssugaugput, ingmingnudlo iliorfigeĸatigĩtariaĸaraluarput ĸatángutigĩtut peĸatigîvnerup anersâvane.

(Post-reform)

- Inuit tamarmik inunngorput nammineersinnaassuseqarlutik assigiimmillu ataqqinassuseqarlutillu pisinnaatitaaffeqarlutik. Silaqassusermik tarnillu nalunngissusianik pilersugaapput, imminnullu iliorfigeqatigiittariaqaraluarput qatanngutigiittut peqatigiinnerup anersaavani.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in English:

- "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."

See also

Notes

- ↑ The CIA World Factbook has reported Greenlandic literacy as being 100 percent since at least 2007, when it also reported six other countries achieving one hundred percent literacy.[3] The Factbook's most recently reported data for Greenland literacy was for 2015.[4]

- ↑ According to the Namminersornerullutik Oqartussat / Grønlands Hjemmestyres (Greenlands Home, official website): " Language. The official languages are Greenlandic and Danish.... Greenlandic is the language [that is] used in schools and [that] dominates in most towns and settlements".[11]

- ↑ The uvular nasal [ɴ] is not found in all dialects and there is dialectal variability regarding its status as a phoneme (Rischel 1974:176–181)

- ↑ Short [t͡s] is in complementary distribution with short [t], with the former appearing before /i/ and the latter elsewhere; both are written ⟨t⟩ and could be analysed as belonging to the same phoneme /t/. Before /i/, long [tt͡s] occurs while long [tt] does not, so long [tt͡s] before /i/ could be analysed as long /tt/. However, before /a/ and /u/, both long [tt͡s] and long [tt] occur (except in some dialects, including that of Greenland's third largest town). Long [tt͡s] is always written ⟨ts⟩, e.g. asavatsigut ‘you love us’, atsa ‘aunt (father's sister)’, Maniitsoq.

- ↑ ⟨ff⟩ is the way of writing the devoiced /vv/ geminate; /rv/ is written ⟨rf⟩; otherwise, ⟨f⟩ occurs only in loanwords.

- ↑ When /l/ is geminated, it is heard as a [ɬɬ] fricative sound.

- ↑ /ʃ/ is found in some dialects (including those of Greenland's two largest towns) but is not distinguished from /s/ in the written language.

- ↑ For example the word Nalunaarasuartaatilioqateeraliorfinnialikkersaatiginialikkersaatilillaranatagoorunarsuarooq, which means something like "Once again they tried to build a giant radio station, but it was apparently only on the drawing board".

- ↑ That can be compared to the English rate, of slightly more than one morpheme per word.

- ↑ For example, the suffix with the shape -aa means "his/hers/its" when it is suffixed to a noun but "him/her/it" when it is suffixed to a verb. Likewise the suffix -ra means "my" or "me", depending on whether it is suffixed on a verb or a noun.

Abbreviations

For affixes about which the precise meaning is the cause of discussion among specialists, the suffix itself is used as a gloss, and its meaning must be understood from context: -SSA (meaning either future or expectation), -NIKUU and -SIMA.

References

- 1 2 Greenlandic at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- 1 2 "Lov om Grønlands Selvstyre" (PDF). Lovtidende (in Danish). 2009-06-13. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-05.

Det grønlandske sprog er det oficielle sprog i Grønland.

- ↑ "Country Comparison to the World of Literacy Rate". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. May 2007. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ↑ "People and Culture: Literacy". Greenland. World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. May 2023. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023.

- ↑ International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (2007), "Greenland", World Report 2007 Country Reports (PDF), IFLA, pp. 175–176, archived from the original on 11 June 2023

- 1 2 3 4 Rischel, Jørgen. Grønlandsk sprog. Den Store Danske Encyklopædi Vol. 8, Gyldendal

- 1 2 Goldbach & Winther-Jensen (1988)

- ↑ Iutzi-Mitchell & Nelson H. H. Graburn (1993)

- ↑ Michael Jones, Kenneth Olwig. 2008. Nordic Landscapes: Region and Belonging on the Northern Edge of Europe. U of Minnesota Press, 2008, p. 133

- ↑ Louis-Jacques Dorais. 2010. The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, Semantics, and Society in the Arctic. McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP, p. 208-9

- ↑ "Culture and Communication". Archived from the original on 2009-02-27. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ↑ UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger Archived 2009-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Greenland". CIA World Factbook. 2008-06-19. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "Sermersooq will secure Eastern Greenlandic". Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa (in Danish). 2010-01-06. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ↑ Fortescue (1991) passim

- ↑ Mennecier(1995) p 102

- ↑ Mahieu & Tersis (2009) p. 53

- ↑ Fortescue, Michael (1990), "Basic Structures and Processes in West Greenlandic" (PDF), in Collins, Dirmid R. F. (ed.), Arctic Languages: An Awakening, Paris: UNESCO, p. 317, ISBN 978-92-3-102661-4

- ↑ Rischel (1974) pp. 79 – 80

- ↑ Jacobsen (2000)

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 16

- 1 2 3 Hagerup, Asger (2011). A Phonological Analysis of Vowel Allophony in West Greenlandic. NTNU.

- ↑ Petersen, Robert, De grønlandske dialekters fordeling [The distribution of the Greenlandic dialects] (PDF) (in Danish) – via Oqaasileriffik [Greenlandic Language Secretariat]

- ↑ Rischel (1974) pp.173–177

- ↑ "grønlandsk | lex.dk". Den Store Danske (in Danish). Retrieved 2022-11-11.

- ↑ Sadock (2003), p. 12

- ↑ Sadock (2003) pp. 3 & 8

- ↑ Fortescue & Lennert Olsen (1992) p. 112

- ↑ Sadock (2003) p. 11

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) pp. 33–34

- 1 2 Bjørnum (2003)

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 71

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) pp. 71–72

- ↑ Langgård, Karen (2009) "Grammatical structures in Greenlandic as found in texts written by young Greenlanders at the turn of the millennium" chapter 15 in Mahieu & Tersis (2009) pp. 231–247 [sic]

- ↑ Fortescue (1993) p. 269

- ↑ Fortescue (1993) p. 269-270

- ↑ Fortescue(1984) p. 34

- ↑ Fortescue (1993) p. 270

- ↑ Bittner (1995) p. 80

- ↑ Fortescue 1991. 53 ff.

- ↑ Woodbury (1983)

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) pp. 152–154

- ↑ Kappel Schmidt (2003)

- 1 2 3 Sadock (2003)

- ↑ Fortescue (1984) p. 92 & p. 249

- ↑ Hallman, Peter (n.d.) "Definiteness in Inuktitut" p. 2

- ↑ van Geenhoven (1998)

- ↑ Bittner (1987)

- ↑ Shaer (2003)

- ↑ Bittner (2005)

- ↑ Hayashi& Spreng (2005)

- ↑ Fortescue (1980) note 1

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 35-50

- ↑ Fortescue & Lennert Olsen (1992) pp. 112 and 119–122)

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 39

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 40-42

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 45

- ↑ Bjørnum(2003) pp. 43–44

- ↑ Bjørnum(2003) pp.46–49

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) pp. 50–51

- ↑ Fortescue (1984:) p. 273

- ↑ Trondhjem (2009) pp. 173–175

- 1 2 3 Fortescue (1984) p. 273

- 1 2 3 4 Trondhjem (2009) p. 174

- ↑ Bittner (2005) p. 7

- ↑ Fortescue (1984) pp. 276–287. The dividing line between lexical aspect, aspect and still other functions that do not fit into those categories has yet to be clarified.

- ↑ Fortescue (1984) pp. 272–273

- ↑ Trondhjem (2009) p. 177

- 1 2 Trondhjem (2009) p. 179

- ↑ cp. Trondhjem (2009) p. 180

- ↑ Trondhjem (2009) pp. 179–180

- ↑ cp. Bittner (2005) p. 36

- ↑ Bittner (2005) pp. 12–13; translation of 15 altered. Glosses standardised to the system used in this article.

- ↑ Fortescue (1984)

- ↑ Trondhjem (2009)

- ↑ Bittner (2005) pp. 11, 38–43

- ↑ https://septentrio.uit.no/index.php/nordlyd/article/view/10/9 Schmidt, Bodil Kappel. 2003. West Greenlandic antipassive

- ↑ Sakel, Jeanette. 1999. Passive in Greenlandic

- ↑ Sadock (1980)

- ↑ Sadock(1986)

- ↑ Sadock (1999)

- ↑ "Malouf (1999)" (PDF). sdsu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-07-12. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ van Geenhoven (2002)

- ↑ Marianne Mithun "Polysynthesis in the Arctic" in Mahieu and Tersis (2009).

- ↑ Mithun (1986)

- ↑ Mithun (1984)

- ↑ Rosen (1989)

- ↑ Fortescue (1984) p. 71

- ↑ Sadock (2003) p. 5

- ↑ Fortescue (1984) p. 252

- ↑ Kappel Schmidt (2003) passim

- ↑ Bittner (1987) passim

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 73

- 1 2 3 Bjørnum (2003) p.74

- 1 2 Bjørnum (2003) p. 75

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 239

- ↑ Bjørnum (2003) p. 86

- ↑ Dorais, Louis-Jacques (2010). The Language of the Inuit: Syntax, semantics, and society in the Arctic. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 9780773536463.

- ↑ Grønlands sprognævn (1992)

- ↑ Petersen (1990)

- ↑ Everson, Michael (2001-11-12). "The Alphabets of Europe: Greenlandic/kalaallisut" (PDF). Evertype. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-09-06.

- ↑ "Programs for analysing Greenlandic". giellatekno.uit.no. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

Sources

- Bittner, Maria (1987). "On the Semantics of the Greenlandic Antipassive and Related Constructions" (PDF). International Journal of American Linguistics. 53 (2): 194–231. doi:10.1086/466053. S2CID 144370074. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-06.

- Bittner, Maria (1995). "Quantification in Eskimo". In Emmon W. Bach (ed.). Quantification in natural languages. Vol. 2. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-3129-2.

- Bittner, Maria (2005). "Future discourse in a tenseless language" (PDF). Journal of Semantics. 12 (4): 339–388. doi:10.1093/jos/ffh029.

- Bjørnum, Stig (2003). Grønlandsk grammatik (in Danish). Atuagkat. ISBN 978-87-90133-14-6.

- Fortescue, Michael (1980). "Affix Ordering in West Greenlandic Derivational Processes". International Journal of American Linguistics. 46 (4): 259–278. doi:10.1086/465662. JSTOR 1264708. S2CID 144093414.

- Fortescue, Michael (1984). West Greenlandic. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7099-1069-5.

- Fortescue, Michael (1991). "Switch reference anomalies and 'topic' in west greenlandic: A case of pragmatics over syntax". In Jef Verschueren (ed.). Levels of Linguistic Adaptation: selected papers of the International Pragmatics Conference, Antwerp, August 17–22, 1987, volume II. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. ISBN 978-1-55619-107-7.

- Fortescue, Michael (1991). Inuktun: An introduction to the language of Qaanaaq, Thule. Institut for Eskimologi, Københavns Universitet. ISBN 978-87-87874-16-8.

- Fortescue, Michael & Lise Lennert Olsen (1992). "The Acquisition of West Greenlandic". In Dan Isaac Slobin (ed.). The Crosslinguistic study of language acquisition, vol 3. Routledge. pp. 111–221. ISBN 978-0-8058-0105-7.

- Fortescue, Michael (1993). "Eskimo word order variation and its contact-induced perturbation". Journal of Linguistics. 29 (2): 266–289. doi:10.1017/S0022226700000335. JSTOR 4176235. S2CID 144656468.

- van Geenhoven, Veerle (1998). Semantic incorporation and indefinite descriptions: semantic and syntactic aspects of noun incorporation in West Greenlandic. Stanford: CSLI Publications. ISBN 978-1-57586-133-3.

- van Geenhoven, Veerle (2002). "Raised Possessors and Noun Incorporation in West Greenlandic". Natural Language & Linguistic Theory. 20 (4): 759–821. doi:10.1023/A:1020481806619. S2CID 189900856.

- Goldbach, Ib & Thyge Winther-Jensen (1988). "Greenland: Society and Education". Comparative Education. 24 (2, Special Number (11)): 257–266. doi:10.1080/0305006880240209.

- Grønlands sprognævn (1992). Icelandic Council for Standardization. Nordic cultural requirements on information technology. Reykjavík: Staðlaráð Íslands. ISBN 978-9979-9004-3-6.

- Hayashi, Midori & Bettina Spreng (2005). "Is Inuktitut tenseless?" (PDF). In Claire Gurski (ed.). Proceedings of the 2005 Canadian Linguistics Association Annual Conference. 2005 CLA Annual Conference. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-08. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- Iutzi-Mitchell, Roy D. & Nelson H. H. Graburn (1993). "Language and educational policies in the North: Status and Prospectus report on the Eskimo–Aleut languages from an international symposium". International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 1993 (99): 123–132. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1993.99.123. S2CID 152185608.

- Kappel Schmidt, Bodil (2003). "West Greenlandic Antipassive". Nordlyd. Proceedings of the 19th Scandinavian Conference of Linguistics. 31 (2): 385–399. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- Mahieu, Marc-Antoine & Nicole Tersis (2009). Variations on polysynthesis: the Eskaleut languages. Typological studies in language, 86. John Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-0667-1.

- Malouf, Robert (1999). "West Greenlandic noun incorporation in a monohierarchical theory of grammar" (PDF). In Gert Webelhuth; Andreas Kathol; Jean-Pierre Koenig (eds.). Lexical and Constructional Aspects of Linguistic Explanation. Studies in constraint-based lexicalism. Stanford: CSLI Publications. ISBN 978-1-57586-152-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2003-07-12. Retrieved 2009-12-23.

- Mennecier, Philippe (1995). Le tunumiisut, dialecte inuit du Groenland oriental: description et analyse. Collection linguistique, 78 (in French). Société de linguistique de Paris, Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-2-252-03042-4.

- Mithun, Marianne (1984). "The evolution of noun incorporation". Language. 60 (4): 847–895. doi:10.2307/413800. JSTOR 413800.

- Mithun, Marianne (1986). "On the nature of noun incorporation". Language. 62 (1): 32–38. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.692.5196. doi:10.2307/415599. JSTOR 415599.

- Petersen, Robert (1990). "The Greenlandic language: its nature and situation". In Dirmid R. F. Collis (ed.). Arctic languages: an awakening. Paris: Unesco. pp. 293–308. ISBN 978-92-3-102661-4.

- Rosen, Sara T. (1989). "Two types of noun incorporation: A lexical analysis" (PDF). Language. 65 (2): 294–317. doi:10.2307/415334. hdl:1808/17539. JSTOR 415334.

- Sadock, Jerrold (1980). "Noun incorporation in Greenlandic: A case of syntactic word-formation". Language. 57 (2): 300–319. doi:10.1353/lan.1980.0036. JSTOR 413758. S2CID 54796313.

- Sadock, Jerrold (1986). "Some notes on noun incorporation". Language. 62 (1): 19–31. doi:10.2307/415598. JSTOR 415598.

- Sadock, Jerrold (1999). "The Nominalist Theory of Eskimo: A Case Study in Scientific Self Deception". International Journal of American Linguistics. 65 (4): 383–406. doi:10.1086/466400. JSTOR 1265857. S2CID 144784179.

- Sadock, Jerrold (2003). A Grammar of Kalaallisut (West Greenlandic Inuttut). Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-234-2.

- Shaer, Benjamin (2003). "Toward the tenseless analysis of a tenseless language" (PDF). In Jan Anderssen; Paula Menéndez-Benito; Adam Werle (eds.). Proceedings of SULA 2. 2nd Conference on the Semantics of Under-represented Languages in the Americas. GLSA, University of Massachusetts Amherst. pp. 139–56.

- Trondhjem, Naja Frederikke (2009). "11. The marking of past time in Kalaallisut, the Greenlandic language". In Mahieu, Marc-Antoine & Nicole Tersis (ed.). Variations on polysynthesis: the Eskaleut languages. Typological studies in language, 86. John Benjamins. pp. 171–185. ISBN 978-90-272-0667-1.

- Woodbury, Anthony C. (1983). "Switch-reference, syntactic organization, and rhetorical structure in Central Yup'ik Eskimo". In John Haiman; Pamela Munro (eds.). Switch-reference and universal grammar. Typological studies in language, 2. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 291–316. ISBN 978-90-272-2862-8.

Further reading

- Fortescue, M. D. (1990). From the writings of the Greenlanders = Kalaallit atuakkiaannit. [Fairbanks, Alaska]: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 0-912006-43-9

External links

- General Usage of the Greenlandic Language Papers at Dartmouth College Library

- Oqaasileriffik (The Greenland Language Secretariat) (version in English): contains many language resources including dictionaries, a speech synthesis program, a morphological analyser and a corpus

- Law of Greenlandic Selfrule (see chapter 7) (in Danish)