John Henry Manley | |

|---|---|

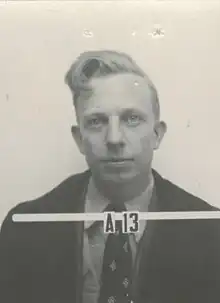

Manley's Los Alamos badge | |

| Born | July 21, 1907 Harvard, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 1990 (aged 82) Los Alamos, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Illinois University of Michigan |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | Columbia University Metallurgical Laboratory Los Alamos Laboratory Washington University in St. Louis |

| Thesis | Collisions of the second kind between magnesium and neon (1935) |

| Doctoral advisor | Ora Stanley Duffendack |

John Henry Manley (July 21, 1907 – June 11, 1990) was an American physicist who worked with J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley before becoming a group leader during the Manhattan Project.[1]

Biography

He was born in 1907 in Harvard, Illinois. He graduated with a BS from the University of Illinois in 1929 and received his PhD in physics from the University of Michigan in 1934. He was a lecturer at Columbia University and later a professor at the University of Illinois from 1937 to 1942. He married Kathleen (Kay), and had two daughters Kim and Kathleen.

By the time World War II broke out, Manley was at the University of Chicago's Metallurgical Laboratory. In 1942, his friend and colleague, J. Robert Oppenheimer, held a meeting with several leading theorists at UC Berkeley. The topic of the meeting: develop preliminary plans to design and build a nuclear weapon. Manley, one of the attendees, was tasked with learning more about the properties of fast neutrons.

Less than a year later, the center of the project had shifted to the Los Alamos Laboratory. Manley received a personal call from Leo Szilard to move to Los Alamos and on April 4, 1943, Manley arrived at the laboratory.[2] Manley spent his first days in Los Alamos working with other newcomers on the construction of laboratory buildings. He also installed a Cockcroft–Walton generator, which he had brought with him from Urbana. Throughout the war Manley served as one of Oppenheimer's principal aides, with particular responsibility for laboratory management.[3] His wife Kay moved to Los Alamos in June 1943, following the birth of their second daughter. She was hired as a human computer in the T (Theoretical) Division but then quit after six months to focus on raising their children.[2][4]

After the war, Manley left Los Alamos to serve as executive secretary of the general advisory committee for the Atomic Energy Commission, a federal agency charged with managing the nation's atomic assets. After leaving the AEC, he returned to Los Alamos as assistant director for research. In 1946, Manley served as associate professor of physics at Washington University in St. Louis for a semester.[5][6] From 1951 to 1957, Manley headed the physics department at the University of Washington. In 1959 he was named a senior technical advisor to the International Atomic Energy Agency. He retired in 1974, and died in 1990 in Los Alamos at age 82.

See also

- Lawrence Badash, J.O. Hirschfelder, H.P. Broida, eds., Reminiscences of Los Alamos 1943–1945 (Studies in the History of Modern Science), Springer, 1980, ISBN 90-277-1098-8.

References

- ↑ Jakobson, Mark; Rosen, Louis (November 1991). "Obituary: John Henry Manley". Physics Today. 44 (11): 113–114. Bibcode:1991PhT....44k.113J. doi:10.1063/1.2810336. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013.

- 1 2 Strottman, Theresa (February 15, 1992). "Kay Manley's Interview". Voices of the Manhattan Project. Los Alamos Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2022.

- ↑ Goldberg, Stanley (1995). "Groves and Oppenheimer: The Story of a Partnership". The Antioch Review. Antioch Review. 53 (4): 491. doi:10.2307/4613224. JSTOR 4613224.

- ↑ Howes, Ruth H.; Herzenberg, Caroline L. (2003). Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project. Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-59213-192-1.

- ↑ "John Manley's Interview (1985) – Part 1". www.manhattanprojectvoices.org. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ↑ "Washington University in St. Louis. Department of Physics". history.aip.org. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

External links

- 1965 Audio Interview with John Manley by Stephane Groueff Voices of the Manhattan Project

- New York Times obituary

- LANL biography