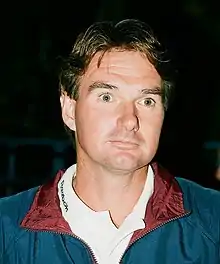

Connors in 1994 | |

| Full name | James Scott Connors |

|---|---|

| Country (sports) | |

| Residence | Santa Barbara, California, U.S. |

| Born | September 2, 1952 Belleville, Illinois, U.S. |

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m)[1] |

| Turned pro | 1972 |

| Retired | 1996 |

| Plays | Left-handed (two-handed backhand) |

| Coach | Gloria Connors Pancho Segura |

| Prize money | $8,641,040 |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1998 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 1274–283 (81.8%)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Career titles | 109 (1st in the Open Era) |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (July 29, 1974) |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1974) |

| French Open | SF (1979, 1980, 1984, 1985) |

| Wimbledon | W (1974, 1982) |

| US Open | W (1974, 1976, 1978, 1982, 1983) |

| Other tournaments | |

| Tour Finals | W (1977) |

| WCT Finals | W (1977, 1980) |

| Doubles | |

| Career record | 174–78 (68.9%)[lower-alpha 1] |

| Career titles | 16 |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | 3R (1974) |

| French Open | F (1973) |

| Wimbledon | W (1973) |

| US Open | W (1975) |

| Team competitions | |

| Davis Cup | W (1981) |

| Coaching career (2006–2015) | |

| |

James Scott Connors (born September 2, 1952)[2] is an American former world No. 1 tennis player. He held the top Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) ranking for a then-record 160 consecutive weeks from 1974 to 1977 and a career total of 268 weeks. By virtue of his long and prolific career, Connors still holds three prominent Open Era men's singles records: 109 titles, 1,557 matches played, and 1,274 match wins. His titles include eight major singles titles (a joint Open Era record five US Opens, two Wimbledons, one Australian Open) and three year-end championships. In 1974, he became the second man in the Open Era to win three major titles in a calendar year, and was not permitted to participate in the fourth, the French Open. Connors finished year end number one in the ATP rankings from 1974 to 1978. In 1982, he won both Wimbledon and the US Open and was ATP Player of the Year and ITF World Champion. He retired in 1996 at the age of 43.

Career

Early years

Connors grew up in East St. Louis, Illinois, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, Missouri, and was raised Catholic. During his childhood he was coached and trained by his mother and grandmother.[3] He played in his first U.S. Championship, the U.S. boys' 11-and-under of 1961, when he was nine years old. Connors's mother, Gloria, took him to Southern California to be coached by Pancho Segura, starting at age 16, in 1968.[4] But she remained part of the team as his coach and manager. He and his brother, John "Johnny" Connors, attended St. Phillip's grade school.

Connors won the Junior Orange Bowl in both the 12- and the 14-year categories, and is one of only nine tennis players to win the Junior Orange Bowl championship twice in its 70-year history. In 1970, Connors recorded his first victory in the first round of the Pacific Southwest Open in Los Angeles, defeating Roy Emerson. In 1971, Connors won the NCAA singles title as a Freshman while attending UCLA and attained All-American status.

He turned professional in 1972 and won his first tournament, the Jacksonville Open. Connors was acquiring a reputation as a maverick in 1972 when he refused to join the newly formed Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), the union that was embraced by most male professional players, in order to play in and dominate a series of smaller tournaments organized by Bill Riordan, his manager. However, Connors played in other tournaments and won the 1973 U.S. Pro Singles, his first significant title, defeating Arthur Ashe in a five-set final, 6–3, 4–6, 6–4, 3–6, 6–2.

Peak years

%252C_Bestanddeelnr_929-6576.jpg.webp)

Connors won eight Grand Slam singles championships: five US Opens, two Wimbledons, and one Australian Open. He did not participate in the French Open during his peak years (1974–78), as he was banned from playing by the event in 1974 due to his association with World Team Tennis (WTT).[5][6] and in the other four years chose not to participate. He played in only two Australian Opens in his entire career, winning it in 1974 and reaching the final in 1975. Few highly ranked players, aside from Australians, travelled to Australia for that event up until the mid-1980s.

Connors is one of thirteen men to win three or more major singles titles in a calendar year. Connors reached the final of the US Open in five straight years from 1974 through 1978, winning three times with each win being on a different surface (1974 on grass, 1976 on clay and 1978 on hard). He reached the final of Wimbledon four out of five years during his peak (1974, 1975, 1977 and 1978). Despite not being allowed to play or choosing not to participate in the French Open from 1974 to 1978, he was still able to reach the semifinals four times in the later years of his career.

In 1974, Connors was the dominant player. He had a 99–4 record that year and won 15 tournaments of the 21 he entered, including three of the four Grand Slam singles titles. As noted, the French Open did not allow Connors to participate due to his association with World Team Tennis (WTT), but he won the Australian Open, which began in late December 1973 and concluded on January 1, 1974, defeating Phil Dent in four sets, and beat Ken Rosewall in straight sets in the finals of both Wimbledon and the US Open losing only 6 and 2 games, respectively, in those finals. His exclusion from the French Open denied him the opportunity to become the second male player of the Open Era, after Rod Laver, to win all four Major singles titles in a calendar year. He chose not to participate in the season-ending Masters Cup between the top eight players of the world and was not eligible for the World Championship Tennis (WCT) finals because he did not compete in the WCT's regular tournaments. Connors finished 1974 at the top of ATP Point Rankings.[7] He also was the recipient of the Martini and Rossi Award, voted for by a panel of journalists[8] and was ranked World No. 1 by Rex Bellamy,[9] Tennis Magazine (U.S.),[10] Rino Tommasi,[11] World Tennis,[12] Bud Collins,[13] Judith Elian[14] and Lance Tingay.[15]

In 1975, Connors reached the finals of Wimbledon, the US Open and Australia, but he did not win any of them, although his loss to John Newcombe was close as Connors lost 9–7 in a fourth set tiebreak. He won nine of the tournaments he entered achieving an 82–8 record. While he earned enough points to retain the ATP No. 1 ranking the entire year and was ranked number one by Rino Tommasi,[11] all other tennis authorities, including the ATP, named Arthur Ashe, who solidly defeated Connors at Wimbledon, as the Player of the Year. He once again did not participate in the Masters Cup or the WCT Finals.

In 1976, Connors captured the US Open once again (defeating Björn Borg) while losing in the quarter-finals at Wimbledon. While winning 12 events, including the U.S. Pro Indoor in Philadelphia, Palm Springs and Las Vegas, he achieved a record of 90–8 and defeated Borg all four times they played. He was ranked No. 1 by the ATP for the entire year and was ranked number one by World Tennis,[16] Tennis Magazine (U.S.),[17] Bud Collins,[18] Lance Tingay,[15] John Barrett,[19] and Tommasi.[11] The ATP named Björn Borg as its player of the year.

In 1977, an injured Connors lost in the Wimbledon finals to Borg 6–4 in the fifth set and in the US Open finals to Guillermo Vilas, but Connors captured both the Masters, beating Borg, and the WCT Finals. While holding onto the ATP No. 1 ranking, World Tennis Magazine and most tennis authorities ranked Borg or Vilas No. 1 with Connors rated as No. 3 behind Borg.

In 1978, Borg defeated Connors in the Wimbledon final, but Connors defeated Borg at the US Open (played on hard court for the inaugural time) with both of their victories being dominating. Connors also won the U.S. Pro Indoor. While he retained the ATP No. 1 ranking at the end of the year, the ATP and most tennis authorities rated Borg, who also won the French Open, as the player of the year.

Connors reached the ATP world No. 1 ranking on July 29, 1974, and held it for 160 consecutive weeks, a record until it was surpassed by Roger Federer on February 26, 2007. He was the ATP year-end no. 1 player from 1974 through 1978 and held the No. 1 ranking for a total of 268 weeks during his career. Connors relinquished his initial grip (160 weeks) on the No. 1 ranking for only one week, from August 23 to August 30, 1977, before resuming as No 1 for another 84 weeks.[20]

In 1979 through 1981, Connors generally reached the semi-finals of the three top Grand Slam events and the Masters each year, but he did win the WCT Finals in 1980. He was generally ranked third in the world those years.

In 1982, Connors experienced a resurgence as he defeated John McEnroe in five close sets to win Wimbledon and Ivan Lendl to win the US Open after which he reclaimed the ATP No. 1 ranking. He also reached the semi-final of the Masters Cup and won five other tournaments. After trading the No. 1 ranking back and forth with McEnroe, he finished the year ranked No. 2 in points earned, but he was named Player of the Year by the ATP and was ITF World Champion due to his victories at Wimbledon and the US Open.

In 1983, Connors, McEnroe and Lendl traded the No. 1 ranking several times with Connors winning the US Open for a record fifth time (beating Lendl in the final) and finishing the year as the No. 3 ranked player.

Contemporaries and rivalries

Prominent contemporary players with Connors included Phil Dent, Brian Gottfried, Raul Ramírez, Harold Solomon, Dick Stockton, Roscoe Tanner, and Guillermo Vilas. His older rivals included Arthur Ashe, Rod Laver, Ilie Năstase, John Newcombe, Manuel Orantes, Ken Rosewall, and Stan Smith. His prominent younger opponents included Björn Borg, Vitas Gerulaitis, Ivan Lendl, and John McEnroe.

Björn Borg

During his best years of 1974 through 1978, Connors was challenged the most by Borg, with twelve matches on tour during that time frame. Borg won only four of those meetings, but two of those wins were in the Wimbledon finals of 1977 and 1978. Connors lost his stranglehold on the top ranking to Borg in early 1979 and wound up with an official tour record of 8–15 against Borg as Borg is four years younger and won the last ten times they met. Head to head in major championship finals, they split their four meetings, Borg winning two Wimbledons (1977 & 1978) and Connors winning two US Opens (1976 & 1978).

Ilie Năstase

Nastase was another rival in Connors's prime. Though six years older than Connors, Nastase won ten of their first eleven meetings. However, Connors won 11 of their final 14 meetings. The two would team up to win the doubles championships at the 1973 Wimbledon and the 1975 US Open.

Manuel Orantes and Guillermo Vilas

Orantes upset Connors in the final of the 1975 US Open, but Connors was 11–3 overall against Orantes in tour events. On the other hand, Vilas wore down Connors in the final of the 1977 US Open and was much more competitive in all of their meetings. Connors was able to manage only a 5–4 record against Vilas in tour events.

Rod Laver and John Newcombe

In 1975, Connors won two highly touted "Challenge Matches", both arranged by the Riordan company and televised nationally by CBS Sports from Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada. The first match, in February and billed as $100,000 ($543,847 today) winner-takes-all, was against Laver. Connors won that match, 6–4, 6–2, 3–6, 7–5. In April, Connors met Newcombe in a match billed as a $250,000 winner-takes-all. Connors won the match, 6–3, 4–6, 6–2, 6–4. Connors ended his business relationship with Riordan later in 1975.[3]

Connors played Newcombe in four tour events, with Newcombe winning the first two meetings on grass (1973 US Open quarterfinal and 1975 Australian Open final) and Connors winning the last two on hard courts (1978 Sydney Indoor quarterfinal and 1979 Hong Kong round of 16). Connors won all three meetings with Rod Laver in tour events.

Later years

In 1984 Connors had made both the finals of Wimbledon and the WCT finals with semifinal appearances at the French Open, the US Open, and the Masters Cup. He finished the year as the No. 2 ranked player after McEnroe. In 1985 he made the semi-finals of the big 4 four events and finished number No. 4 for the year, a ranking he would again obtain in 1987 at the age of 35.

Connors had shining moments against John McEnroe and Ivan Lendl, both of whom rose to prominence after Connors peaked in the mid-1970s. He would continue to compete against much younger players and had one of the most remarkable comebacks for any athlete when he reached the semifinals of the 1991 US Open at the age of 39.

John McEnroe

In the 1980 WCT Finals, Connors defeated the defending champion, John McEnroe. In 1982, at age 29, Connors was back in the Wimbledon singles final, where he faced McEnroe, who by then was established firmly as the world's top player. Connors recovered from being three points away from defeat in a fourth-set tie-break (at 3–4) to win the match, 3–6, 6–3, 6–7, 7–6, 6–4, and claimed his second Wimbledon title, eight years after his first.

Although Connors's tour record against McEnroe was 14–20, McEnroe is 6½ years younger than Connors and had a losing record against Connors until he won 12 out of their last 14 meetings. Head to head in major championship finals, they split their two meetings, Connors winning the 1982 Wimbledon in five sets, and McEnroe winning the 1984 Wimbledon in straight sets. McEnroe won six of their nine meetings in Grand Slam events.

Ivan Lendl

Connors defeated another of the next generation of tennis stars, Ivan Lendl, in the 1982 US Open final and soon regained the No. 1 ranking. Connors had a tour record of 13–22 against Lendl, but Lendl is eight years younger than Connors and had a losing record against Connors until he won their last 17 matches from 1984 through 1992, after Connors's prime. Head to head in major championship finals, Connors defeated Lendl in both meetings, winning the 1982 and 1983 US Open.

Other matches

Connors continued to compete against younger men well into his 41st year.

In the fourth round of the 1987 Wimbledon Championships, Connors defeated Mikael Pernfors, ten years his junior, 1–6, 1–6, 7–5, 6–4, 6–2, after having trailed 4–1 in the third set and 3–0 in the fourth set. In July 1988, Connors ended a four-year title drought by winning the Sovran Bank Tennis Classic in Washington, D.C. It was the 106th title of his career. Connors had played in 56 tournaments and lost 11 finals since his previous victory in the Tokyo Indoors against Lendl in October 1984.

At the 1989 US Open, Connors defeated the third seed (and future two-time champion), Stefan Edberg, in straight sets in the fourth round and pushed sixth-seeded Andre Agassi to five sets in a quarterfinal.

His career seemed to be at an end in 1990, when he played only three tournament matches and lost all three, dropping to No. 936 in the world rankings. However, after surgery on his deteriorating left wrist, he came back to play 14 tournaments in 1991. An ailing back forced him to retire from a five-sets match in the third round of the French Open against Michael Chang, the 1989 champion. Connors walked off the court after hitting a service-return winner against Chang on the first point of the fifth set, having just levelled the match by winning the fourth.

Connors recuperated and made an improbable run to the 1991 US Open semifinals which he later said were "the best 11 days of my tennis career".[21] On his 39th birthday he defeated 24-year-old Aaron Krickstein, 3–6, 7–6, 1–6, 6–3, 7–6, in 4 hours and 41 minutes, coming back from a 2–5 deficit in the final set. Connors then defeated Paul Haarhuis in the quarterfinals before losing to Jim Courier. 22 years later ESPN aired a documentary commemorating Connors's run.[22]

Connors participated in his last major tournament, in the 1992 US Open, where he beat Jaime Oncins, 6–1, 6–2, 6–3 in the first round, before losing to Lendl (then ranked No. 7), 6–3, 3–6, 2–6, 0–6 in the second round.

In September 1992, Connors played Martina Navratilova in the third Battle of the Sexes tennis match at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas, Nevada. Connors was allowed only one serve per point and Navratilova was allowed to hit into half the doubles court. Connors won, 7–5, 6–2.

However, this would not be the end of his playing career. As late as June 1995, three months shy of his 43rd birthday Connors beat Sébastien Lareau, 6–4, 7–6, and Martin Sinner, 7–6, 6–0, to progress to the quarterfinals of the Halle event in Germany. Connors lost this quarterfinal, 6–7, 3–6 to Marc Rosset. Connors's last match on the main ATP tour came in April 1996, when he lost, 2–6, 6–3, 1–6, to Richey Reneberg in Atlanta.[23]

Maverick

In 1974, Connors and Riordan began filing lawsuits, amounting to $10 million, against the ATP and its president, Arthur Ashe, for allegedly restricting his freedom in the game. The lawsuits stemmed from the French Open banning Connors in 1974 after he had signed a contract to play World Team Tennis (WTT) for the Baltimore Banners. Connors was seeking to enter the French Open, but the ATP and French officials opposed WTT because of scheduling conflicts, so the entries of WTT players were refused between 1974 and 1978. Connors dropped Riordan and eventually the lawsuits after losing to Ashe in the 1975 Wimbledon final (according to the official film produced by Wimbledon 1975, his $2 million suit against Ashe was still outstanding when the two met in the 1975 Wimbledon final).

At Wimbledon in 1977, he declined to participate in a parade of former champions to celebrate the tournament's centenary, choosing instead to practice in the grounds with Ilie Nastase while the parade took place. In 2000, he also declined to join a gathering of 58 former champions held to mark the millennium. In his 2013 autobiography, Connors blamed his missing the 1977 parade on the All England Club for not letting his doctor onto the grounds so that Connors could try on a customized splint for a thumb injury. Connors explained that this necessitated his rushing to meet the doctor at the entrance to the grounds, and then convincing Nastase to help him try out the splint on a practice court. By Connors's account, he then rushed to Centre Court for the parade, but was too late. Reaching the 1977 final, he lost in five sets to Björn Borg, who a month later was able briefly to interrupt Connors's long hold on the world No. 1 ranking.

Connors also irritated sponsors and tennis officials by shunning the end-of-year Masters championship from 1974 through 1976. However, he entered this round-robin competition in 1977 when it moved to New York City. Although Connors lost a celebrated late-night match to Vilas, 4–6, 6–3, 5–7, he took the title by defeating Borg in the final, 6–4, 1–6, 6–4.

Distinctions and honors

Connors is often considered among the greatest tennis players in the history of the sport.[24] Connors won a male record 109 singles titles.[25] He also won 16 doubles titles (including the men's doubles titles at Wimbledon in 1973 and the US Open in 1975). Connors has won more matches (1,274) than any other male professional tennis player in the open era. His career win–loss record was 1,274–282 for a winning percentage of 82.4.[26] He played 401 tournaments, a record until Fabrice Santoro overtook it in 2008.[27]

In Grand Slam Singles events, Connors reached the semifinals or better a total of 31 times and the quarterfinals or better a total of 41 times, despite entering the Australian Open Men's Singles only twice and not entering the French Open Men's Singles for five of his peak career years. The 31 semifinals stood as a record until surpassed by Roger Federer at Wimbledon 2012. The 41 quarterfinals remained a record until Roger Federer surpassed it at Wimbledon 2014. Connors was the only player to win the US Open on three different surfaces: grass, clay, and hard. He was also the first male tennis player to win Grand Slam singles titles on three different surfaces: grass (1974), clay (1976), and hard (1978).

Connors was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1998 and Intercollegiate Tennis Association (ITA) Hall of Fame in 1986. He also has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[28] In his 1979 autobiography, tennis promoter and Grand Slam winning player Jack Kramer ranked Connors as one of the 21 best players of all time. Because of his fiery competitiveness and acrimonious relationships with a number of peers, he has been likened to baseball player Pete Rose.[22] In 1983, Fred Perry ranked the greatest male players of all time and put them in to two categories, before World War II and after. Perry's modern best behind Laver: "Borg, McEnroe, Connors, Hoad, Jack Kramer, John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall, Manuel Santana".[29]

Playing style

In the modern era of power tennis, Connors's style of play has often been cited as highly influential, especially in the development of the flat backhand. Larry Schwartz on ESPN.com said about Connors, "His biggest weapons were an indomitable spirit, a two-handed backhand and the best service return in the game. It is difficult to say which was more instrumental in Connors becoming a champion. ... Though smaller than most of his competitors, Connors didn't let it bother him, making up for a lack of size with determination."[30] Of his own competitive nature Connors has said, "[T]here's always somebody out there who's willing to push it that extra inch, or mile, and that was me. (Laughter) I didn't care if it took me 30 minutes or five hours. If you beat me, you had to be the best, or the best you had that day. But that was my passion for the game. If I won, I won, and if I lost, well, I didn't take it so well."[2]

His on-court antics, designed to get the crowd involved, both helped and hurt his play. Schwartz said, "While tennis fans enjoyed Connors's gritty style and his never-say-die attitude, they often were shocked by his antics. His sometimes vulgar on-court behavior—like giving the finger to a linesman after disagreeing with a call or strutting about the court with the tennis racket handle between his legs; sometimes he would yank on the handle in a grotesque manner and his fans would go wild or groan in disapproval—did not help his approval rating. During the early part of his career, Connors frequently argued with umpires, linesmen, the players union, Davis Cup officials and other players. He was even booed at Wimbledon—a rare show of disapproval there—for snubbing the Parade of Champions on the first day of the Centenary in 1977."[30] His brash behavior both on and off the court earned him a reputation as the brat of the tennis world. Tennis commentator Bud Collins nicknamed Connors the "Brash Basher of Belleville" after the St Louis suburb where he grew up.[31] Connors himself thrived on the energy of the crowd, positive or negative, and manipulated and exploited it to his advantage in many of the greatest matches of his career.[32]

Connors was taught to hit the ball on the rise by his teaching-pro mother, Gloria Connors, a technique he used to defeat the opposition in the early years of his career. Gloria sent her son to Southern California to work with Pancho Segura at the age of 16. Segura advanced Connors' game of hitting the ball on the rise which enabled Connors to reflect the power and velocity of his opponents back at them. In the 1975 Wimbledon final, Arthur Ashe countered this strategy by taking the pace off the ball, giving Connors only soft junk shots (dinks, drop shots, and lobs) to hit.

In an era when the serve and volley was the norm, Björn Borg excepted, Connors was one of the few players to hit the ball flat, low, and predominantly from the baseline. Connors hit his forehand with a semi-Western grip and with little net clearance.[33] Contemporaries such as Arthur Ashe and commentators such as Joel Drucker characterized his forehand as his greatest weakness, especially on extreme pressure points, as it lacked the safety margin of hard forehands hit with topspin. His serve, while accurate and capable, was never a great weapon for him as it did not reach the velocity and power of his opponents.

His lack of a dominating serve and net game, combined with his individualist style and maverick tendencies, meant that he was not as successful in doubles as he was in singles, although he did win Grand Slam titles with Ilie Năstase, reached a final with Chris Evert, and accumulated 16 doubles titles during his career.

Racket evolution

At a time when most other tennis pros played with wooden rackets, Connors used the "Wilson T2000" steel racket, which utilized a method for stringing that had been devised and patented by Lacoste in 1953.[34][35] He played with this chrome tubular steel racket until 1984, when most other pros had shifted to new racket technologies, materials, and designs.[35]

At the Tokyo Indoor in October 1983, Connors switched to a new mid-size graphite racket, the Wilson ProStaff, that had been designed especially for him and he used it on the 1984 tour.[36] But 1985 again found Connors playing with the T2000. In 1987, he finally switched to a graphite racket when he signed a contract with Slazenger to play their Panther Pro Ceramic. In 1990, Connors signed with Estusa.[35]

Connors used lead tape which he would wind around the racket head to provide the proper "feel" for his style of game.

Commentating

Connors did commentary with NBC-TV in 1990 and 1991, during its coverage of the French Open and Wimbledon tournaments. During the Wimbledon tournaments of 2005, 2006, and 2007, Connors commentated for the BBC alongside John McEnroe (among others), providing moments of heated discussion between two former archrivals. Connors returned to BBC commentary at Wimbledon in 2014. Connors has also served as a commentator and analyst for the Tennis Channel since the US Open tournament of 2009.[37]

Coaching

On July 24, 2006, at the start of the Countrywide Classic tournament in Los Angeles, American tennis player Andy Roddick announced his partnership with Connors as his coach. In September, 2006 Roddick reached the final of the U.S. Open, where he lost to Roger Federer. On March 6, 2008, Roddick announced the end of that 19-month relationship.

In July 2013 former women's world No. 1 Maria Sharapova announced on her website that Connors was her new coach. On August 15, 2013, Sharapova confirmed that she had ended the partnership with Connors after just one match together.

Author

In 2013, Connors published his autobiography The Outsider. It won the British Sports Book Awards in the "Best Autobiography/Biography" category.[38]

Personal life

Connors was engaged to fellow tennis pro Chris Evert from 1974 to 1975, and they each triumphed in the singles events at the 1974 Wimbledon Championships, a feat labelled "The Lovebird Double" by the media. Their engagement was broken off shortly before the 1975 Wimbledon championship. Connors and Evert briefly reconciled in 1976 and 1978, before parting for good. In May 2013, Connors wrote his autobiography in which he alleged that Evert was pregnant with their child and that she unilaterally made the decision to have an abortion.[39][40][41]

Former Miss World Marjorie Wallace was engaged to Connors from 1976 to 1977, but in 1979 Connors married Playboy model Patti McGuire. They have two children, son Brett and daughter Aubree, and live in the Santa Barbara, California, area.[42][43]

In the fall of 1988, Connors auditioned to host the NBC daytime version of Wheel of Fortune, a show of which he and his wife "never missed an episode".[44] However, the job went to Rolf Benirschke. According to show creator Merv Griffin, many news outlets tried to get their hands on Connors' audition tape, but Griffin refused to release it because he said "it wouldn't have been fair to Jimmy."[45]

In the 1990s, he joined his brother John as an investor in the Argosy Gaming Company, which owned riverboat casinos on the Mississippi River. The two owned 19 percent of the company which was headquartered in the St. Louis metropolitan area of East Alton, Illinois.[46] Argosy narrowly averted bankruptcy in the late 1990s and Connors' brother John personally sought Chapter 7 bankruptcy. In the liquidation, Connors, through his company, Smooth Swing, acquired the Alystra Casino in Henderson, Nevada, for $1.9 million from Union Planters Bank, which had foreclosed on John. In 1995, John Connors had opened the casino with announced plans to include a Jimmy Connors theme area.[47] It was shuttered in 1998 and became a magnet for the homeless and thieves who stripped its copper piping. The casino never reopened under Connors' ownership and it was destroyed in a May 2008 fire.[48]

In October 2005, Connors had successful hip-replacement surgery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.[49]

On January 8, 2007, Connors' mother Gloria died at age 82.[50]

On November 21, 2008, Connors was arrested outside an NCAA basketball game between the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of California at Santa Barbara after refusing to comply with an order to leave an area near the entrance to the stadium.[51] The charges were dismissed by a judge on February 10, 2009.[52][53]

On July 24, 2018, LiveWire Ergogenics, Inc. announced that Connors joined the firm as a spokesman and advisor. The company focuses on special purpose real estate acquisitions and the licensing and management of fully compliant turnkey production facilities for cannabis-based products and services.[54]

In December 2019, Connors appeared as himself on season 18 episode 9 of Family Guy titled Christmas is Coming.

Career statistics

Singles performance timeline

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | DNQ | A | NH |

| Tournament | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | SR | W–L | Win % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Slam tournaments | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian Open | A | A | A | A | A | W | F | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | NH | A | A | A | A | A | A | 1 / 2 | 11–1[55] | 91.67 | ||||

| French Open | A | A | A | 2R | 1R | A | A | A | A | A | SF | SF | QF | QF | QF | SF | SF | A | QF | A | 2R | A | 3R | 1R | 0 / 13 | 40–13 | 75.47 | ||||

| Wimbledon | A | A | A | QF | QF | W | F | QF | F | F | SF | SF | SF | W | 4R | F | SF | 1R | SF | 4R | 2R | A | 3R | 1R | 2 / 20 | 84–18 | 82.35 | ||||

| US Open | LQ | 1R | 2R | 1R | QF | W | F | W | F | W | SF | SF | SF | W | W | SF | SF | 3R | SF | QF | QF | A | SF | 2R | 5 / 22 | 98–17 | 85.22 | ||||

| W–L | 0–0 | 0–1 | 1–1 | 5–3 | 8–3 | 20–0 | 17–3 | 11–1 | 12–2 | 13–1 | 15–3 | 15–3 | 14–3 | 18–1 | 14–2 | 16–3 | 15–3 | 2–2 | 14–3 | 7–2 | 6–3 | 0–0 | 9–3 | 1–3 | 8 / 57 | 233–49 | 82.62 | ||||

| Year-end championships | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Masters Cup | SF | SF | W | RR | SF | SF | RR | SF | SF | SF | RR | 1 / 11 | 18–17 | 51.43 | |||||||||||||||||

| WCT Finals | W | RR | W | F | SF | 2 / 5 | 10–3 | 76.92 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| W–L | 2–2 | 2–2 | 7–1 | 1–1 | 3–3 | 6–1 | 1–2 | 1–1 | 1–1 | 3–2 | 1–1 | 0–3 | 3 / 16 | 28–20 | 58.33 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ranking | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 936 | 49 | 84 | $ 8,641,040 | ||||||||||

- Australian Open was held twice in 1977, in January and December. Connors did not play these tournaments.

Records

- These records were attained in Open Era of tennis.

- Combined tours included Association of Tennis Professionals, Grand Prix Circuit, World Championship Tennis.

- Records in bold indicate peer-less achievements.

| Time span | Selected Grand Slam tournament records | Players matched |

|---|---|---|

| 1974 | 100% (20–0) match winning percentage in 1 season | Rod Laver |

| 1972 Wimbledon — 1991 Wimbledon | 107 grass court match wins | Stands alone |

| 1974–1985 | 12 consecutive years with match winning percentage of 80%+ | Stands alone |

| 1974 US Open | Shortest final (by duration and number of games) vs. Ken Rosewall[lower-alpha 2][56] | Stands alone |

| Grand Slam tournaments | Time span | Records at each Grand Slam tournament | Players matched | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Open | 1974 | Won title on the first attempt | Roscoe Tanner Vitas Gerulaitis Johan Kriek Andre Agassi | |

| US Open | 1974–1983 | 5 titles overall | Pete Sampras Roger Federer | [57] |

| 1974 (grass) 1976 (clay) 1978 (hard) | 3 titles on 3 different surfaces | Stands alone | [58] | |

| 1974–1985 | 12 consecutive semifinals | Stands alone | [59] | |

| 1974–1991 | 14 semifinals | Stands alone | ||

| 1973–1985 | 13 consecutive quarterfinals | Stands alone | ||

| 1973–1991 | 17 quarterfinals | Stands alone | ||

| 1971–1992 | 98 match wins | Stands alone | [59] | |

| 1970–1992 | 115 matches played | Stands alone | [59] | |

| 1970–1992 | 22 tournaments played | Stands alone | [59] |

| Time span | Other selected records | Players matched |

|---|---|---|

| 1972–1989 | 109 career titles[58] | Stands alone |

| 1972–1989 | 48 WCT titles | Stands alone |

| 1971–1989 | 164 career finals | Stands alone |

| 1970–1995 | 1274 career matches won[60] | Stands alone |

| 1970–1996 | 1557 career matches played | Stands alone |

| 1973 | 9 hard court titles in 1 season | Roger Federer |

| 1974 | 4 grass court titles in 1 season | Stands alone |

| 1972–1989 | 53 career indoor titles | Stands alone |

| 1972–1989 | 79 career indoor finals | Stands alone [61] |

| 1972–1984 | 45 carpet court titles | Stands alone |

| 1970–1993 | 486 indoor match wins | Stands alone |

| 1970–1991 | 392 carpet court match wins | Stands alone |

| 1973–1984 | 12 consecutive years with match winning percentage of 80%+ | Stands alone |

| 1972–1980 | 9 consecutive years winning 5+ titles | Stands alone |

| 1972–1984 | 13 consecutive years winning 4+ titles | Stands alone |

| 1973–1978 | 4 years winning 10+ titles | Ivan Lendl |

| 1974–1975 | 2 winning streaks of 35+ matches | Björn Borg Roger Federer |

| 1974 | 44 consecutive sets won | Stands alone |

| 1975–1978 | 3 calendar years as wire-to-wire No. 1 | Roger Federer |

| 1973–1984 | Ended 12 consecutive years ranked inside the top 3 | Stands alone |

| 1973–1986 | 651 consecutive weeks ranked inside the top 4 | Stands alone |

| 1973–1986 | 659 consecutive weeks ranked inside the top 5 | Stands alone |

| 1976–1980 | 4 U.S. Pro Indoor singles titles | Rod Laver John McEnroe Pete Sampras |

| 1973–1984 | 4 Los Angeles Open singles titles | Andre Agassi Roy Emerson Frank Parker |

Professional awards

- ITF World Champion: 1982

- ATP Player of the Year: 1974, 1982

- ATP Comeback Player of the Year: 1991

See also

Notes

- 1 2 At Grand Slam, Grand Prix tour, WCT tour, ATP Tour level, and in Davis Cup.

- ↑ The final took 1 hour, 18 minutes to complete in 20 games.[56]

References

- ↑ "Jimmy Connors". atpworldtour.com. ATP Tour. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- 1 2 "Holding Court". Vogue. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on June 24, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Frank Deford (August 28, 1978). "Raised by women to conquer men". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ↑ Caroline Seebohm: Little Pancho (2009)

- ↑ John Barrett, ed. (1975). World of Tennis '75. London: Queen Anne Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-362-00217-1.

- ↑ "Connors, Goolagong 'Can't Play'". The Palm Beach Post. May 22, 1974.

- ↑ "Singles ranking 1974.12.20". Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP). Archived from the original on April 17, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ↑ "Statesman Journal (Salem), 25 February 1975". newspapers.com. February 25, 1975. Archived from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ↑ The Times (London), 3 January 1975, p. 6

- ↑ "Hartford Courant, 16 December 1974". newspapers.com. December 16, 1974. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Almanacco illustrato del tennis 1989, Edizioni Panini, p.694

- ↑ "Tennis Rankings: In With New, Out With Old". Fort Lauderdale News. December 18, 1975. p. 73. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ↑ Collins & Hollander (1997), p. 651

- ↑ Quidet, Christian (1989). La Fabuleuse Histoire du Tennis (in French). Paris: Nathan. p. 772. ISBN 9782092864388.

- 1 2 Barrett, John, ed. (1990). World Of Tennis. London: Collins Willow. pp. 235–237. ISBN 9780002183550.

- ↑ "Jimmy Back on Top". The Tampa Times. December 15, 1976. p. 22. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ↑ "The Vancouver Sun, 17 December 1976". newspapers.com. December 17, 1976. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ↑ Collins & Hollander (1997), p. 652

- ↑ The Financial Times

- ↑ "ATP Singles Rankings". ATP Tour. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Jimmy Connors faces Aaron Krickstein in reunion match". USA Today. February 10, 2015. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- 1 2 ESPN's 30 for 30 documentary This is What They Want Archived July 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ ATP World Tour, Official Website. Player Information Jimmy Connors. Main Website http://www.atpworldtour.com/ Archived August 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Tennis magazine ranked Connors the third best male player of the period 1965–2005.

- ↑ James Scott Connors- International Hall of Fame Archived November 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Fighter's mentality made him the best". Los Angeles Times. September 26, 1993. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ↑ James Scott Connors Archived November 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". St. Louis Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ "The Miami Herald, 25 April 1983". newspapers.com. April 25, 1983. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- 1 2 "ESPN: Connors conquered with intensity". go.com. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ Bud Collins Joins ESPN Archived March 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Oddo, Chris. "Connors has no apologies, for his career or book". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ↑ "Excerpts from How to Play Tougher Tennis by Jimmy Connors: QuickSports Tennis". quickfound.net. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ↑ "Racket history". itftennis.com. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Jimmy Connors (USA) 80s-tennis.com". 80s-tennis.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved April 4, 2008.

- ↑ John Barrett, ed. (1984). World of Tennis 1984 : The Official Yearbook of the International Tennis Federation. London: Willow Books. p. 150. ISBN 0-00-218122-3.

- ↑ Ex-Tennis Great Jimmy Connors to Work for Tennis Channel Archived January 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine SI.com, January 28, 2009

- ↑ "British Sports Book Awards 2014". British Sports Book Awards. May 21, 2014. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- ↑ Jimmy, Connors (2013). The Outsider. New York City, NY: Bantam/HarperCollins. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-593-06927-1.

- ↑ Jimmy, Connors (May 10, 2013). "Today Show Interview". NBC News Today Show. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ Chase, Chris (May 2, 2013). "Jimmy Connors implies Chris Evert was pregnant with his child". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Connors still swaggering after all these years". The Guardian. June 21, 2006. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 3, 2019.

- ↑ "'Lovebird Double' who ruled Wimbledon", The Independent (London), June 19, 2004. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ↑ E! True Hollywood Story: Wheel of Fortune. (television program) E! Network, 2005.

- ↑ Griffin, Merv. Merv: Making the Good Life Last. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003, page 103.

- ↑ "History of Argosy Gaming Company – International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 21. St. James Press, 1998". fundinguniverse.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Alystra to rise again? – Las Vegas Business Press – January 29, 2007". Archived from the original on January 28, 2013. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Mike Trask (May 17, 2008). "Fire settles casino's fate for good". LasVegasSun.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Wright Medical Group, Inc. Teams Up With Jimmy Connors for Dynamic Patient Education Outreach Program". Business Wire. August 14, 2006. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ↑ "Gloria Connors, 82; son inherited passion for tennis". Boston Globe. Associated Press. January 14, 2007. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Tennis great Jimmy Connors arrested". CNN. November 22, 2008. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved May 18, 2012.

- ↑ Jimmy Connors Cleared! Archived February 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine TMZ.com, February 10, 2009

- ↑ "Charges dropped against tennis great Connors". February 12, 2009. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ↑ "LiveWire Ergogenics Welcomes Legendary Tennis Champion Jimmy Connors as Spokesman and Advisor". Globenewswire.com (Press release). July 24, 2018. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ↑ "Australian Open Draws". Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- 1 2 "Year by Year – History – 1974". US Open. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ↑ "US Open Most Championship Titles Record Book" (PDF). US Open. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- 1 2 Wancke, Henry. "Wimbledon Legends – Jimmy Connors". Wimbledon.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "US Open Singles Record Book" (PDF). US Open. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 6, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ↑ "Tribute: Federer Records 1200th Match Win In Madrid". ATP Tour. May 9, 2019. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ↑ Garcia, Gabriel. "Record: Most Finals Indoor Open Era". app.thetennisbase.com. Madrid, Spain: Tennismem SL. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

Further reading

- Collins, Bud; Hollander, Zander (1997). Bud Collins' Tennis Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Detroit: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 978-1578590001.

- Sabin, Francene (1978). Jimmy Connors, King of the Courts. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-61115-0.

- Henderson Jr., Douglas (2010). Endeavor to Persevere: A Memoir on Jimmy Connors, Arthur Ashe, Tennis and Life. Untreed Reads. ISBN 978-1-61187-039-8.

- Seebohm, Caroline, (2009), Little Pancho

Video

- Charlie Rose with Jimmy Connors (August 7, 1995) Studio: Charlie Rose, DVD Release Date: October 5, 2006, ASIN: B000JCF3S8

- Biography: Jimmy Connors DVD A&E 2002.

- Jimmy Connors Presents Tennis Fundamentals: Comprehensive, Starring: Jimmy Connors; Chris Evert, Foundation Sports, DVD Release Date: May 1, 2006, Run Time: 172 minutes, ASIN: B000FVQWCY.

- Wimbledon 1975 Final: Ashe vs. Connors Standing Room Only, DVD Release Date: October 30, 2007, Run Time: 120 minutes, ASIN: B000V02CTQ.

.jpg.webp)