Birds in Chinese mythology and legend are of numerous types and very important in this regard. Some of them are obviously based on real birds, other ones obviously not, and some in-between. The crane is an example of a real type of bird with mythological enhancements. Cranes are linked with immortality, and may be transformed xian immortals, or ferry an immortal upon their back. The Vermilion Bird is iconic of the south. Sometimes confused with the Fenghuang, the Vermilion Bird of the south is associated with fire. The Peng was a gigantic bird phase of the gigantic Kun fish. The Jingwei is a mythical bird which tries to fill up the ocean with twigs and pebbles symbolizing indefatigable determination. The Qingniao was the messenger or servant of Xi Wangmu.

Names and translation

Written and spoken Chinese varieties have different character graphs and sounds representing mythological and legendary birds of China.

Characters

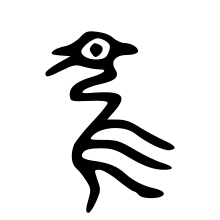

The Chinese characters or graphs used have varied over time calligraphically or typologically. Historically main generic characters for bird are niǎo (old school, traditional character = 鳥 / simplified character, based on cursive form = 鸟) and the other main "bird" word / character graph zhuī (隹). Many specific characters are based on these two radicals; in other words, incorporating one or the other radical as constituent to a more complex character graph, for example in the case of the Peng bird (traditional character graph = 鵬 / simplified = 鹏): in both cases, a version of the niǎo character is radicalized on the right.

Spoken word

Modern pronunciations vary and the ancient ones are not fully recoverable. Sometimes the Chinese terms for mythological or legendary birds include a generic term for "bird" appended to the pronounced name for "bird"; an example would be the Zhenniao, which is also known just as Zhen: the combination of Zhen plus niao means "Zhen bird"; thus, "Zhenniao" is the same as "Zhen bird", or just "Zhen".

Translation

Translation into English language of Chinese terms for legendary and mythological birds is difficult, especially considering that even in Chinese there is a certain amount of obscurity. In some cases, the classical Chinese term is obviously a descriptive term. In other cases, the classical Chinese term is clearly based on the alleged sound of said bird; that is, what is known as onomatopoeia. However, often, it's not so simple (Strassberg 2002, xvii–xviii).

Auspicious birds

Very auspicious birds include the Feng, the Fenghuang, and the Luan (Strassberg 2002, 102 sub XI:49).

Symbolically representative birds

Some birds in Chinese legend and mythology symbolize or represent various concepts of a more-or-less abstract nature.

Directional Bird

The Vermilion Bird of the South symbolically represents the cardinal direction south. It is red and associated with the wu xing "element" fire.

Persistence

The Jingwei bird represents determination and persistence, even in the face of seemingly over-whelming odds.

Totem birds

Some birds may function as totems or representative symbols of clans or other social groups.

Associated birds

Some birds are associated with other mythological content.

Three-legged Bird of the Sun

A three-legged bird or birds are a solar motif. Sometimes depicted as a Three-legged crow.

Messenger bird

The Qingniao is associated with the Queen Mother of the West, bearing her messages or bringing her food (Yang 2005, 219 and Christie 1968, 78).

Features of mythological geography

Some birds feature as part of visions of the mythological geography of China. According to the Shanhaijing and it's commentaries, the Bifang can be found on Mount Zhang'e and/or east of the Feathered People (Youmin) and west of the Blue River (Strassberg 2002, 110 and 163)

Transportation

Certain birds in mythology transport deities, immortals, or others. One example is the Crane in Chinese mythology.

Various birds

Other birds include the Bi Fang bird, a one-legged bird (Strassberg 2002, 110–111). Bi is also number nineteen of the Twenty-Eight Mansions of traditional Chinese astronomy, the Net (Bi). There are supposed to be the Jiān (鶼; jian1): the mythical one-eyed bird with one wing; Jianjian (鶼鶼): a pair of such birds dependent on each other, inseparable, hence representing husband and wife. There was a Shang-Yang rainbird. The Jiufeng is a nine-headed bird used to scare children. The Sù Shuāng (鷫鷞; su4shuang3) sometimes appears as a goose-like bird. The Zhen is a poisonous bird. There may be a Jiguang (吉光; jíguāng).

Real birds

The line between fantastic, mythological, or legendary birds and actually real exotic birds is sometimes blurred. Sometimes, the student of the real versus the unreal becomes challenged.

Sources

Various sources for information on Chinese legends and mythology about bird. This includes the Shanhaijing (Stassberg 2002, passim). Also, "Questions to Heaven" (Stassberg 2002, 11 and Yang et al. 2005, 8–10).

See also

Main article

Relevant categories

- Category:Mythological and legendary Chinese birds

- Category:Legendary birds

- Category:Birds in mythology

Related

References

- Christie, Anthony (1968). Chinese Mythology. Feltham: Hamlyn Publishing. ISBN 0600006379

- Ferguson, John C. 1928. "China" in Volume VIII of Mythology of All Races. Archaeological Institute of America. <archive.org>

- Hawkes, David, translator and introduction (2011 [1985]). Qu Yuan et al., The Songs of the South: An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044375-2

- Schafer, Edward H. (1963) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Strassberg, Richard E., editor, translator, and comments. 2002 [2018]. A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the GUIDEWAYS THROUGH MOUNTAINS AND SEAS. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29851-4

- Wu, K. C. (1982). The Chinese Heritage. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-517-54475X.

- Yang, Lihui and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner (2005). Handbook of Chinese Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533263-6