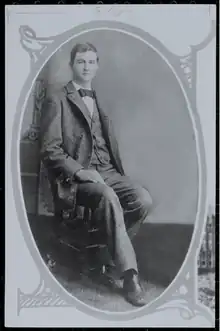

Jesse Jones | |

|---|---|

(b).jpg.webp) | |

| 9th United States Secretary of Commerce | |

| In office September 19, 1940 – March 1, 1945 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Harry Hopkins |

| Succeeded by | Henry A. Wallace |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jesse Holman Jones April 5, 1874 Robertson County, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | June 1, 1956 (aged 82) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Mary Gibbs (m. 1920) |

Jesse Holman Jones (April 5, 1874 – June 1, 1956) was an American Democratic politician and entrepreneur from Houston, Texas. Jones managed a Tennessee tobacco factory at age fourteen, and at nineteen, he was put in charge of his uncle's lumberyards. Five years later, after his uncle, M. T. Jones, died, Jones moved to Houston to manage his uncle's estate and opened a lumberyard company, which grew quickly. During this period, Jesse opened his own business, the South Texas Lumber Company. He also began to expand into real estate, commercial building, and banking. His commercial building activities in Houston included mid-rise and skyscraper office buildings, hotels and apartments, and movie theaters. He constructed the Foster Building, home to the Houston Chronicle, in exchange for a fifty percent share in the newspaper, of which he acquired control in 1926.

Jones's participation in civic life and politics began with the Port of Houston and the Houston Ship Channel. He led a group of local bankers in buying public finance bonds and was later appointed to serve as the Chair of the Houston Harbor Board. He led a local fundraising effort on behalf of the American Red Cross in support of servicemen in World War I. President Wilson tapped Jones to head a division of American Red Cross, a duty he fulfilled between 1917 and 1919. In 1928, he initiated and organized Houston's bid for the 1928 Democratic National Convention.

Jones most important role was in the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) (1932–1939), a federal agency originally created in the Herbert Hoover administration which played a major role in combating the Great Depression and financing industrial expansion during World War II. After Hoover first appointed Jones to the board, President Franklin D. Roosevelt expanded the powers of the RFC and promoted Jones to the chairmanship in 1933. Jones was in charge of spending US$50 billion, especially in financing railways and building munitions factories.[1] He served as the United States secretary of commerce from 1940 to 1945, a post he held concurrently with his chairmanship of the RFC. With the combined authority of these various federal posts, Jones was arguably the second most powerful person in the nation, which is confirmed by Roosevelt's nickname for him, "Jesus Jones".

After leaving Washington, Jesse and Mary Jones focused on philanthropy, working through the Houston Endowment, a non-profit corporation they founded in 1937. Though most of this giving was focused on Texas, some of it flowed to Tennessee and Massachusetts. Much of their philanthropy concentrated on education, including large gifts for a business school at Texas Southern University and another to establish Jones College at Rice University. However, they also made substantial donations to hospitals and for the arts. Many buildings in Houston are named for Jesse Jones, including a music venue in downtown Houston known as Jones Hall.

Family history and early life

Jesse H. Jones descended from Welsh ancestors who made Virginia their first landing place in North America, sometime in the 1650s. After settling there briefly, they relocated to the Chowan River in North Carolina, remaining there for at least a century. In 1774, Eli Jones and one of his brothers, headed west, eventually deciding to an area now known as Robertson County, Tennessee. William, one of Eli's sons, established himself as a farmer there, and married a neighboring farmer's daughter, Laura Anna Holman. The farm was sufficient to provide for all of the needs of the family and grow tobacco for sale, partly from their own efforts, and partly from the work of enslaved persons.[2]

Jesse Holman Jones was born to William and Laura Jones on April 5, 1874, the fourth of five children.[2] Jesse's mother died on April 22, 1880, just after he had turned six. Nancy Jones Hurt, his aunt, moved in with the family along with her two sons. She was a "guide, physician, and clothes-maker of all the Jones children," and "a famous cook".[3] Sudley Place was his childhood home.[4]

In 1883, the Jones family, including Aunt Nancy and seven children moved to Dallas, Texas, partly in order for William to join his brother Martin Tilton "M.T." Jones in his successful lumber enterprise. Several years earlier M.T. had resettled his family in Terrell, Texas after a stop in Illinois. Aunt Nancy remained in Dallas and enrolled the children in local public schools, while William moved to Terrell to manage the M.T. Jones Lumber Company and look after the firm's other lumberyards in northeast Texas. This allowed M.T. to move closer to his timberlands and other interests in southeast Texas. However, William only stayed for two years and returned with his large family to Robertson County, where he acquired a new farm to work. So Jesse was back in Tennessee at the age of twelve.[5] The new estate of William Jones included 600 acres, and the patriarch built a spacious brick house with ten rooms to accommodate his large family. According to one biographer, this house was "the finest outside of Nashville."[6] Later in life, Jesse recollected that the family farm was bountiful, providing enough meat and produce to leave a surplus through all seasons. They even shared food with less fortunate neighbors who struggled during the winter months, Jones recalled.[7]

Jesse had been a diligent worker as a boy, caring for the farm animals, and performing many common household chores. During the summers when his family had lived in Dallas—when he was a young teenager—he hacked out weeds, picked cotton, and herded cattle. He did not display the same diligence for school, and later, Jesse recalled many scoldings and punishments from his teachers.[8] His father challenged his two sons with a tobacco plot for each of them. He allotted three acres to each son and provided them both with supplies. Each of them would be allowed to keep any profits after they repaid their store accounts. He applied this experience to a job in the tobacco industry when he quit school after the eighth grade. William Jones not only grew tobacco, but also traded the crop, and he also joined a partnership, Jones, Holman and Armstrong, which processed tobacco. William put Jesse in charge of one of the tobacco factories. He was responsible for receiving (or sometimes rejecting), classifying, warehousing, and shipping tobacco. In addition, his name was on the company bank account, and he signed checks for the company's operations.[9]

At the age of seventeen, Jesse and his family returned to Dallas. After several attempts to find a suitable job in Dallas and the surrounding region, Jesse started working in Hillsboro, Texas, at one of his uncle's lumberyards. He performed manual labor, but also served the office side of the business, such as bookkeeping and debt collection. Despite these varied duties, he earned the standard salary for a salesman: $40 per month. He requested a fifty percent raise, arguing that he worked day and night. His uncle refused. Jesse quit not long before the death of his father, William Jones. The will instructed that trustees manage the tobacco enterprise, while Jesse would assume control at age twenty-one. He also inherited about $2,000 in stock.[10]

Business activities

Timber and lumber

.jpg.webp)

Jesse and his brother liquidated the tobacco inventory from their father's estate and spent the proceeds on their sisters' homes. Jesse returned to Dallas and applied for a position with the M.T. Jones Lumber Company's downtown yard on Main Street and St. Paul. M. T. refused to hire him, leading Jones to wonder if his former supervisor in Hillsboro had reported unfavorably on him. An investigation of the Hillsboro yard, however, revealed that its manager had committed fraud. The general manager of the company, C. T. Harris, fired that manager and hired Jesse as bookkeeper for the big Dallas yard. Initially, Jesse earned a salary of $15 per week—more than he made at the Hillsboro yard. After just six months, Harris made Jesse the manager there, raising his salary to $100 per month (equivalent to $2,900 in 2016). Harris made these decisions without consulting M.T., the owner of the company.[11] Jesse ran the Dallas yard profitably, even in the face of eight competitors in the local market. In 1895, with M.T. still critical of the Dallas operations, Jesse tendered his resignation. However, M.T. audited the books of the Dallas yard and found them to be in good order. M.T. asked Jesse to retract his resignation. Jesse replied that he would take his old job back for $150 per week and six percent of the profits. M.T. agreed to Jesse's terms.[12]

While Jesse was still managing a lumber yard in Dallas for M.T. Jones, he decided on a financial gambit while competing for the lumber trade related to the 1897 Texas State Fair in Dallas. The association running the State Fair needed construction supplies for buildings and exhibits, but the lumber companies wanted personal guarantees from the directors. Jesse, sensing an opportunity, decided to stand out from his competitors: he extended credit to the State Fair Association, with only the backing of gate receipts. When M.T. found out about the terms of the loans and the full extent of Jesse's gamble, he began to investigate Jesse's activities and interrogated him about his decision. These loans were repaid quickly and the Dallas lumber yard profited from the play.[13]

Despite these confrontations between M.T. and Jesse, by 1898, it was apparent that Jesse had earned his uncle's trust. M.T. died that year and his will named Jesse as general manager of his substantial lumber business.[6] The will also designated Jesse as one of five executors of his estate. He arrived in Houston in 1898, renting a room at the old Rice Hotel for $2.25 per night (equivalent to $65 in 2016). He was then responsible for the business affairs of his Aunt Louisa and his three cousins. Jesse managed a large estate:[14]

He was now in charge of tens of thousands of acres of timberland spread over three east Texas counties and parts of Louisiana. The estate owned and operated sawmills and factories in Orange that had the daily capacity to turn hundreds of thousands of feet of raw timber into shingles, doors, windows sashes, and two-by-fours. The logistics was equally huge: felled trees had to be moved to plants, and finished products had to be delivered to lumberyards located throughout the state and beyond. With assistance and advice from trustees, Jones bought, sold, and managed the land, expanding the M.T. Jones Lumber Company even further.[14]

In 1902, Jones started the South Texas Lumber Company. He had money he had earned from selling investments in timber and some Spindletop deals for capital. He acquired the Reynolds Lumber Company, as well as many other lumberyards in New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas. The company charter announced an intention to purchase raw goods (lumber), semi-finished goods (cross ties), and milled goods, such as blinds, doors, and sash.[15] According to his own recollection, he made about $1 million in profits when he sold controlling interest in the company, liquidating most of his interests in one saw mill and perhaps 20 or more lumberyards. Other than retaining a single lumberyard, he permanently left active management of the timber and lumber business in 1911 or 1912.[16]

Construction and real estate

_(14586870940).jpg.webp)

Jones began a flurry of building activity in 1906. He contracted to build an addition to the Bristol Hotel, committing $90,000 (equivalent to $1,800,000 in 2016) to the project, which would include a rooftop garden and dance floor. He also commissioned a ten-story building for the Texas Company (Texaco), and the company moved its headquarters to Houston in 1916. The same year, he constructed a new plant for the rapidly growing Houston Chronicle in exchange for a half-interest in the company, which had been solely owned by Marcellus Foster.[17] In 1911, Jones purchased the original five-story Rice Hotel from Rice University although the university retained the land on which it stood. Working with Captain James A. Baker, the president of Rice Institute's Board of Trustees, he razed the original structures and constructed the seventeen-story building, which he then leased from Rice. The new Rice Hotel leased 500 rooms, and was the center of Houston social life.[18]

After concluding his service with the Red Cross, Jones returned to Houston and resumed his business activities. He amassed lots along the Main Street corridor in downtown Houston, acquired a tract on Elm Street in Dallas, and also invested in Fort Worth.[19] In 1921, he expanded one downtown Houston structure into the Bankers Mortgage Building, while laying out plans for two more ten-story buildings. During this time he continued a collaboration with local architect Alfred C. Finn, with whom he had first worked on the Rice Hotel. Jones juggled his Houston program with a development initiative in New York City, and he built the Melba Theater in Dallas.[20]

In the mid-1920s, Jones increased his construction and development activity. Two new buildings, the Kirby Theater and the Kirby Lumber Company Building went up on Main Street, while he built additions to the Rice Hotel and the Houston Electric Building. During the same period he started projects in Manhattan. The first was an apartment building on 1158 Fifth Avenue at 97th Street, followed by the Mayfair House on Park Avenue at 67th Street. A third building at 200 Madison Avenue faced J.P. Morgan's home, with four floors leased to the first Marshall Field's store in New York City.[21][22] Jones also left his mark on Fort Worth, building the Medical Arts Building, and the Worth Hotel and Worth Theater.[21]

In addition to his real estate and political activity associated with Houston's Democratic National Convention, Jones continued multiple development projects in 1928 in other cities. He commissioned an eighteen-story, mixed-use building in downtown Fort Worth, leasing the storefront and two more floors to the Fair Department Store. He sited a sixteen-story medical office building on 61st Street as just one of his projects in New York. Back in Houston, several projects were under construction with no connection to the convention. Jones broke ground on the Gulf Building that year, while completing the Levy Brothers Department Store. The Gulf Building was completed the next year as the tallest structure in Houston, a distinction it held until 1963. He finished another retail building on Main Street, a four-story store for Krupp and Tuffly Shoes. He acquired his fourth hotel, a distressed sixteen-story building which he re-branded as the Texas State Hotel.[23] Jones built in New York a 44-story office tower at 275 Madison Avenue and 40th Street, his largest project to date. He completed it in the spring prior to the Stock Market Crash of 1929.[23][22]

Banking

As a young man, Jones found opportunities to borrow money in order to establish credit. He borrowed in excess of his need, and kept the extra cash in a savings account.[24] However, at least two Houston bankers expressed concerns about his borrowing practices. By his own estimate, he had borrowed as much as $3 million (equivalent to $61,300,000 in 2016). The test came with the Panic of 1907. One of the largest and oldest of Houston's banks, the T. W. House Bank, failed amidst this economic recession. The bank had a $500,000 (equivalent to $9,600,000 in 2016) loan on its books in the name of Jesse Jones. Yet even during the bank panic, Jones was able to sell enough mortgage paper and draw on enough credit from other banks to repay the loan. So he stood ready to make new investments after the worst of the recession ended.[25]

Sometime after 1908, Jones organized the Texas Trust Company. By 1912, he had become president of Houston's National Bank of Commerce. This bank later merged with Texas National Bank in 1964 to become the Texas National Bank of Commerce, renamed to Texas Commerce Bank which grew into a major regional financial institution. It became part of JP Morgan Chase & Co. in 2008.[26]

In 1931 two local banks were in danger of failing. Public National Bank faced a clientele demanding cash and Houston National Bank had too many distressed loans. Public National Bank had barely enough cash on hand to last through Saturday, October 24. The next day, Jones hosted a meeting of local bankers at his office in the new Gulf Building. He urged his banking colleagues to assist in stabilizing the two distressed banks to prevent a general panic among local depositors. Jones proposed a bailout plan of $1.25 million (equivalent to $16,200,000 in 2016) to guarantee local deposits at risk, with the political support of a major local bank investor, James A. Baker. Despite a faction of bankers who wanted to let the two banks fail, Jones and Baker prevailed, with Jones buying out Public National Bank, Joseph Meyers Interests buying out Houston National Bank, and a consortium of banks and utility companies all contributing to the bailout fund. Customers of Public National Bank gained access to their accounts on October 26.[27]

Publishing

Jones acquired his fifty-percent interest in the Houston Chronicle from Marcellus Elliot Foster in August 1906.[28][29] Though Foster was the paper's editor, Jones's engagement in the paper's positions was evident by the letters between the two men. For example, Jones supported Foster's public opposition to the Ku Klux Klan, which had been a growing movement in Texas after World War I. Foster stressed his editorial independence, while Jones vowed that he was willing to risk financial loss and personal safety to side against the KKK.[30] This relationship became strained in 1925 when Jones voiced his opposition to Foster's support of Miriam Ferguson for governor of Texas. They were in agreement with her strong stance against the Klan, but Jones refused to support her candidacy because of the corruption of her husband during his tenure as governor.[31]

In 1926, Jones became the sole owner of the Houston Chronicle and named himself as publisher. At the time of the purchase, the paper had a daily readership of 75,000 and the company was valued at $2.5 million (equivalent to $28,000,000 in 2016).[29] When Jones opened the Gulf Building in Houston, his ownership of the Houston Chronicle facilitated publication of a 48-page special insert dedicated to his new skyscraper.[32] In March 1930, Jones acquired a radio station and began broadcasting in Houston from the Rice Hotel. The call letters of the station, KTRH, used three letters as an acronym for The Rice Hotel.[33] KTRH broadcast some content of the Columbia Broadcasting System, making it the second radio station in Houston to air national programs. Jones established the station to support the Houston Chronicle, which had already seen the Houston Post establish a radio affiliate, KPRC.[33]

Political activities

Houston Ship Channel

.jpg.webp)

Jones helped to secure funding for the Houston Ship Channel. When bond sales for the Harris County Houston Ship Channel District lagged, he met with Houston bankers and extracted a pledge from each one to buy the district's bonds proportionate to their market capitalizations. He was appointed as chair of the new Houston Harbor Board in 1913 by Mayor Ben Campbell.[34] Jones accepted this post after rejecting several offers from the Woodrow Wilson Administration the same year. Edward Mandell House, who advocated Wilson's nomination for the Democratic Party the previous year, suggested Jones for service to the new US President. The Wilson Administration offered positions to Jones such as the undersecretary of the treasury, two ambassadorships, and most notably, secretary of commerce.[35] Jones confronted Mayor Campbell and other interests in regard to a wharf at Manchester, which was at that time outside the city limits. Campbell advocated spending $300,000 of Houston Harbor District revenue to construct a wharf for a local cement manufacturer. Jones opposed this expenditure, and resigned from the board with other directors when the city approved the project.[36]

American Red Cross

From 1917 until the end of World War II, Jones dedicated his activities to the nation, spending more time in the federal capital than in his home town.[37] He responded to World War I demands by leading a fundraising effort in Houston for the American Red Cross. Sixteen of his friends accepted his challenge to donate $5,000 each (equivalent to $100,000 in 2016), spurring the local effort to meet and exceed its fundraising quota.[38] President Wilson asked Jones to become director general of military relief for the American Red Cross during World War I, a position he held until 1919.[26] During his first post in Washington, D.C., his department was responsible for seven hundred Red Cross canteens and 55,000 volunteers, organization and transportation of mobile hospitals to England and France, and distribution of clothing to persons in war-torn Europe, and tendering financial assistance to families of American servicemen.,[39]

Jones worked in an office building facing the White House, and eventually he had personal access to the president. During the coordination of Red Cross parades in various American cities, he asked that the president make a speech on the day of the parade in New York City to support fundraising efforts. Wilson was reticent and had not made an oral public address since his declaration of war against Germany. Jones, per Wilson's request, appointed Cleveland Dodge as the presiding officer of the event, though Jones also directed Dodge to choose a venue suitable for a presidential address. On the day of the parade, President Wilson made an impromptu speech to a full Metropolitan Opera House, which included his justification for war against Germany, lauded the work of the American Red Cross, admonished Wall Street bankers against wartime profiteering, and offered an entreaty to Americans to donate money to the Red Cross.[40]

1928 Democratic National Convention

On his own initiative, Jones tendered a $200,000 bid (equivalent to $2,300,000 in 2016) to bring the 1928 Democratic National Convention to Houston. Other cities matched or exceeded this amount, but Jones vowed that Houston would beat the others in hospitality. When Jones returned to Texas from Washington, D.C., where he had been negotiating, local greeters mobbed the train depots in Marshall, Texas and Conroe, with a few brandishing "Jesse Jones for President" signs. At Union Station, 50,000 Houstonians staged a homecoming for Jones, replete with marching bands, bunting, and banners. They staged a parade from Union Station to the Jones home at the Lamar Hotel. This hero's welcome preceded the decision by the Democratic Convention to select a site, though Walter Lippman and the New York Evening Post predicted that Houston would be chosen.[41]

Reconstruction Finance Corporation

After President Hoover signed the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) bill in 1932, the Republican chose Jones as one of the three to serve on its first board of directors, and managed Defense Plant Corporation. When Hoover sought advice from ranking Democrats about candidates for the board, Jones was the sole recommendation of House Speaker John Nance Garner.[42] The Hoover RFC was an ambitious program. Upon opening, the RFC had 300 staff positions available. Soon it conveyed hundreds of millions in loans, including $300 million (equivalent to $4,400,000,000 in 2016) to the railroads, $90 million to prop up the Chicago bank of Charles Dawes, and $65 million to Bank of America. However, Hoover sold the RFC as a program to assist smaller institutions. Bank of America retired its loan with the RFC, paying interest and principal within two years. Other loans were not successful. Jones opposed a loan to the Missouri Pacific, concerned that the taxpayers would be stuck with their bill. Without Jones's support, the RFC board approved $23 million for the railroad, but it did not prevent the company from failing the next year.[43]

In 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made him the Chairman of the RFC, while also expanding the RFC's powers to make loans and bail out banks. This led some to refer to Jones as "the fourth branch of government."[44] The next year, Congress issued an additional $850 in loans, after which President Roosevelt intimated to Jones that he would have the authority to invest the new appropriations and reinvest revenue from loan repayments.[45]

Jones criticized Hoover's execution of the RFC as too little and too late. Congress and the new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, created a new Emergency Banking Act on March 9, 1933. President Roosevelt announced a "bank holiday," a moratorium on banking activity while federal bank inspectors examined the books in order to determine which financial institutions were viable. After the bank holiday, all financially sound banks would resume business. For persons who were unable to access their accounts, another part of the act authorized the executive branch to reorganize failed banks in order to free up frozen assets. The RFC was empowered to invest financial institution through their preferred stocks. Seventy percent of America's banks reopened after just six days. Jones's task as the new chair of the RFC was to reopen another 2,000 banks. He began with the reorganization of two of Detroit's largest banks by collaborating with Alfred P. Sloan of General Motors. They formed a new bank with matching investments from the RFC and General Motors, but more significantly, the RFC covered the deposits of the 800,000 frozen accounts from both failed banks with a loan of $230 million (equivalent to $3,500,000,000 in 2016).[46]

In the first three years of the Roosevelt Administration, the RFC had issued $8 billion in loans; however, these outflows were offset by $3.5 billion in revenues, including interest payments and repayments of principal.[47] In 1939, Roosevelt appointed Jones to be the new Federal Loan Administrator while taking away his title as RFC chair.[48]

Secretary of Commerce

President Woodrow Wilson offered Jones the position of United States secretary of commerce, but Jones decided instead to remain in Houston and focus on his businesses.[44] He accepted the same position from President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, and he served until 1945.[26] However, according to Stephen Fenberg, Roosevelt offered him the cabinet position to bring him closer to the White House and rein in his power. This tactic did not work because Jones accepted the new post while retaining his old job as Federal Loan Administrator.[49] Jones was also on a short list to serve as Roosevelt's running mate in 1940. Though the nomination for the vice-presidency had been decided by the Democratic convention delegates in previous election cycles, the decisions at the 1940 convention in Chicago were being manipulated by the president. Roosevelt rejected Jones as a running mate because he considered him to be too conservative to properly serve his agenda.[50]

Exit from Washington

Henry Wallace was dropped from the ticket as Vice President in 1944. Roosevelt was reelected and asked Jones to resign as secretary of commerce, which he did on January 21, 1945. The next day he resigned from RFC and all other government positions.[51] Jones released the two letters to several newspapers, including The New York Times. The letters criticized Roosevelt's decision to name Wallace as secretary of commerce. Senator Josiah Bailey of North Carolina called both Jones and Wallace to testify before the Senate Commerce Committee, each on consecutive days. Jones testified on the first day that he did not believe that Wallace was a suitable candidate. He characterized Wallace as a visionary who lacked business experience. Sometime during the five hours of testimony the next day, Wallace touted his own business experience, but sought to restrict the scope of power from the Commerce Department and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which he claimed were exploited by business interests.[52] Steven Fenberg, the author of the most recent biography of Jones, characterized him as the second most powerful person in America next to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who sometimes called him "Jesus Jones."[53]

Zoning proponent

Jones returned to Houston early in 1948. In January, he had already found a new political project, and used his Houston Chronicle as a platform. He expressed concern about "undesirable [commercial] encroachments" and advocated for land use zoning as a method for protecting residential areas.[54] Hugh Roy Cullen led the effort to prevent new zoning regulation for land development in the city of Houston. This was in response to Jones and other zoning advocates in Houston. Cullen believed zoning regulations to be socialist and un-American.[55] Though Jones attracted attention to the zoning issue, his involvement started very late in the struggle, as he published his first opinion in the Houston Chronicle less than two weeks before the vote. Jones published Cullen's opinion opposing zoning in Houston. He accused Jones of being an outsider because Jones had lived away from Houston for twenty-five or thirty years. In addition, he charged Jones with trying to run the city with the "assistance of New York Jews,"[56] and vowed to resign his chair at the Board of Regents at the University of Houston. Jones published Cullen's commentary and his own response to it in the Houston Chronicle two days before the zoning vote. Jones wrote that many other American cities had zoning in rebuttal to Cullen's claim that zoning was "un-American and German." Houston voted against zoning and Cullen never followed through on his threat to quit his leadership positions at non-profits.[56]

Suite 8F Group

Jones was associated with a group of Houston political and social leaders known as the Suite 8F Group, named for the apartment number at the Lamar Hotel maintained by George and Herman Brown. Jones owned the hotel and resided in the building's penthouse, upstairs from the Browns' suite. The principal members of this group were James Abercrombie, the Brown brothers, Judge James Elkins, Oveta Culp Hobby, William P. Hobby, Robert E. Smith, and Gus Wortham. Historian Joseph Pratt characterized Jones as "the godfather" of the group. The Suite 8F Group began their activities after World War II.[57]

Philanthropy and non-profits

Prior to 1937, Jesse and Mary Jones had given about $1 million to charitable causes. In 1937, they established the Houston Endowment to organize their philanthropic endeavors. Their Commerce Company was already established as a conglomeration of most of the family business interests. They granted about a third of the company's shares to the Houston Endowment, while appointing Milton Backlund, Fred Heyne, and W. W. Moore as the first trustees. During the first seven years, Houston Endowment focused its donations on education.[58]

From 1932, Jones had not cashed any paychecks he earned through his various federal government positions through 1945. In 1946, he signed them all over to the Houston Endowment.[59] At the same time Jones and his wife worked through the Houston Endowment to give this money away, much of it with a focus on education. Through the Houston Endowment, they made a $300,000 grant to the University of Virginia in honor of Woodrow Wilson. They established scholarship funds for the Texas State College for Women, Prairie View A & M University, the University of Tennessee, and Texas A & M University.[60] Later they created an engineering scholarship at Massachusetts Institute of Technology honoring Bill Knudsen and an economics scholarship at Austin College honoring Jesse's brother, John.[61] More ten-year scholarship programs funded students attending Rice University and Texas A & M, and several of the individual recipients were veterans of World War II. Another program supported nursing candidates at the University of Houston.[62] They also made large gifts to the American Red Cross, the Houston Community Chest, the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and the United Jewish Appeal.[63]

In 1946, Jones joined the Board of Trustees of the Texas Medical Center.[64]

In 1956, the Jesse Holman Jones Hospital was built in Springfield, Tennessee to replace the original hospital there.[65]

Jones made a gift of $1 million to Rice University to establish Jones College, which opened in 1957. The name for the all-women's dormitories honored Mary Gibbs Jones.[66]

Honors

The 1902 Notsuoh Festival (Houston spelled backwards) elected Jones as its King Nottoc (cotton spelled backwards). His duty was to rule over the Tekram (market) of Saxet (Texas). This was a gag repeated in Houston from 1899 to 1915, and the week-long festival included dances and parades. The crowning of Jones as King Nottoc after living in Houston for just four years symbolized a quick acceptance into local society.[67]

In 1925, Jones received an honorary Doctor of Law degree from Southwestern University,[68] and another from Oglethorpe University in 1941.[69]

Houston honored Jones with "Jesse H. Jones Day" on December 26, 1934. The pronouncement was made by Houston Mayor Oscar Holcombe. The Scottish Rite Temple provided the venue for a ceremony, where there was the first public viewing of a bronze bust of Jones sculpted by Enrico Cerracchio.[70]

In 1939, the Alabama-Coushatta tribe named Jones Chief Cue-ya-la-na when they accepted him into their community. The name translates as "Yellow Pine," symbolic of the tallest being within their local environment and a being which serves all members of their community.[71]

Personal life

Jones resided at the Rice Hotel in Houston, but he also stayed at "the Boarding House," the home of his aunt, Louisa Jones. Her house was located at the corner of Anita and Main Street, south of downtown Houston. Jones managed the estate of his uncle, M. T. Jones, and continued to act as a business manager for his aunt and his cousins for many years. Much of his social life revolved around them, too. His future wife, Mary Gibbs Jones, was first married to his cousin, Will Jones.[72]

Jones married Mary Gibbs on December 15, 1920.[73] They resided at the Rice Hotel until 1926 when they moved into their penthouse at the new Lamar Hotel. Alfred C. Finn designed and supervised the construction of the building, but Jones hired John Staub to design the interior for their apartment. Audrey Jones, one of Mary's granddaughters, also lived with them.[74] Other members of his extended family maintained apartments at the Lamar. His relationships with some of his business associates were also based on close friendships, so Jones referred to this business network as his "business family."[75]

Death and legacy

Jones retained the title of publisher of the Houston Chronicle until his death on June 1, 1956, at the age of 82. His remains were interred in Houston's Forest Park Cemetery.[26]

The name of Jesse H. Jones is memorialized throughout Houston through many grants from the Houston Endowment. The home of the Houston Symphony is Jesse H. Jones Hall in the Houston Theater District.[76][77]

Texas Southern University founded the Jesse H. Jones School of Business in 1955.[78] After Jones's death the Houston Endowment made donations to Rice University. They established the Jesse H. Jones Chair of Management, and in the 1970s, they granted $10 million to start the Jesse H. Jones Graduate School of Management.[79] The Jesse H. Jones Student Life Center, a recreation facility at the University of Houston–Downtown, was fully funded by the Houston Endowment.[80] Baylor University's central libraries includes the Jesse H. Jones Library.[81] The Jesse H. Jones Physical Education Complex on the campus of Texas Lutheran University in Seguin bears his name.[82]

Jones contributed money to the Houston Academy of Medicine/Texas Medical Center for a new home for its library. This building is known as the Jesse H. Jones Library Building.[83] The Jesse H. and Mary Gibbs Jones Pavilion (1977) connects Memorial Hermann Hospital to the University of Texas Medical School.[84]

Other Jones buildings include the Houston Public Library's Central Library building[85] and the Great Jones Building, the former home of Texaco and briefly the location of Jones's office.[86] Beyond buildings, one may visit the Jesse H. Jones Park and Nature Center in Humble.[87]

Since 1998, the World Affairs Council of Greater Houston has presented the Jesse H. Jones Award.[88]

References

- ↑ Jesse H. Jones & Edward Angly, Fifty Billion Dollars: My Thirteen Years with the RFC (1932–1945) (1951).

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 11.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory--Nomination Form: Sudley Place". National Park Service. United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 2, 2018.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 13–15.

- 1 2 Buenger (2003), p. 67.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 16.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 11–15.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 16–19.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 20–23.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 26.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 30–32.

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), p. 37.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 39.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 50.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 44–46.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 99.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 104–105.

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), pp. 125–127.

- 1 2 Caratzas, Michael (January 13, 2009). "275 Madison Avenue" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. p. 5. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), pp. 169–173.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 32.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp.44–46.

- 1 2 3 4 Lionel V. Patenaude (April 13, 2017). "Jones, Jesse Holman". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 181–183.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 44.

- 1 2 Lucko, Paul M. (February 15, 2017). "Foster, Marcellus Elliot". Handbook of Texas. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 173.

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), p. 181.

- ↑ Sibley (1968), pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Buenger (2003), p. 66.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 68.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 71.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 74–77.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 188– 190.

- 1 2 "Brother, Can You Spare A Billion? The Story of Jesse H. Jones". PBS and Houston Public Media. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

Quickly, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation became a central pillar of Roosevelt's NewDeal.

- ↑ Olson (1988), p. 44.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 201–203.

- ↑ Olson (1988), p. 43.

- ↑ Olson (1988), pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 357.

- ↑ Daniels (2016), p. 81.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 502–512.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 515–518.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 1.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 543.

- ↑ Kiger, Patrick J. (April 20, 2015). "The City with (Almost) No Limits". urbanland.uli.org. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- 1 2 Fenberg (2011), p. 544.

- ↑ Pratt, Joseph (2004). "8F and Many More: Business and Civic Leadership in Modern Houston" (PDF). Houston History. 1 (2). Retrieved September 30, 2018.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp.291–292.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 535.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 531–534.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 538.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 545–546.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 534–535.

- ↑ Elliott (2004), p. 89.

- ↑ Jones, Bill (January 3, 2016). "History-Robertson County Hospital". The Connection. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Jones College: History". Rice University. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 39–40.

- ↑ "Jesse Jones to Speak at Centennial Celebration". The Megaphone. March 12, 1940. Retrieved October 19, 2018 – via Portal to Texas Online.

- ↑ "Honorary Degrees Awarded by Oglethorpe University". Oglethorpe University. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 329.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), pp. 40–42.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 100.

- ↑ Fenberg (2011), p. 134.

- ↑ Buenger (2003), p. 70.

- ↑ "Jones Hall for the Performing Arts". Archived from the original on January 25, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ "Celebrating 50 Years in Jones Hall". The Houston Symphony. October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ↑ "About the JHJ School of Business". Texas Southern University. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ Kean, Melissa. "A Short History of the Jesse H. Jones School of Management" (PDF). rice University. pp. 8–11. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ Castillo, Max (November 17, 1996). "UH-Downtown: A snapshot of the academic future". Houston Business Journal. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Baylor University || University Libraries". Baylor.edu. June 5, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2013.

- ↑ Elliott (2004), pp. 201–202.

- ↑ "History of the Library". The TMC Library. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ Seaholm, Megan (March 7, 2017). "HERMANN HOSPITAL". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association (TSHA). Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Houston Public Library| Central Library, Jesse H. Jones Building". Houston Public Library. September 26, 2014. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ Gonzales, J. R. (December 14, 2010). "The evolution of the Great Jones Building". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Jesse H. Jones Park and Nature Center". Hcp4.net. Harris County, Texas, Precinct 4. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ↑ "The Jesse H. Jones Award". World Affairs Council of Greater Houston. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

Bibliography

- Buenger, Walter L. (2003). "Jesse H. Jones". In Hendrickson, Kenneth E. Jr.; Collins, Michael L. (eds.). Profiles in Power: Twentieth-Century Texans in Washington. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 66–84. ISBN 978-0292798427.

- Daniels, Roger (2016). Franklin D. Roosevelt: The War Years, 1939-1945. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09764-5 – via Project MUSE.

- Elliott, Frederick C. (2004). The Birth Of The Texas Medical Center: A Personal Account. Texas A&M University Press.

- Fenberg, Steven (2011). Unprecedented Power: Jesse Jones, Capitalism, and the Common Good. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-434-7 – via Project MUSE.

- Koistinen, Paul A. C. (2004). Arsenal of World War II: The Political Economy of American Warfare, 1940-1945. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700613083.

- Olson, James Stuart (1988). Saving Capitalism: The Reconstruction Finance Corporation and the New Deal, 1933-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04749-2. JSTOR j.ctt1m322tm.

- Sibley, Marilyn McAdams (1968). The Port of Houston: A History. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Further reading

- Herman, Arthur (2012). Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- Jones, Jesse H.; Angly, Edward (1951). Fifty Billion Dollars: My Thirteen Years with the RFC (1932–1945). New York: Macmillan Company.

- Mason, Joseph R. (2003). "The Political Economy of Reconstruction Finance Corporation Assistance During the Great Depression". Explorations in Economic History. 40 (2): 101–121. doi:10.1016/S0014-4983(03)00013-5.

- Schwarz, Jordan A. The New Dealers: Power politics in the age of Roosevelt (Vintage, 2011) pp 59-95. online

- Sprinkel, Beryl Wayne (1952). "Economic Consequences of the Operations of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation". Journal of Business of the University of Chicago. 25 (4): 211–224. doi:10.1086/233060. JSTOR 2350206.

- Timmons, Bascom N. (1956). Jesse Jones: The Man and the Statesman. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

- White, Gerald Taylor (1980). Billions for Defense: Government Financing by the Defense Plant Corporation During World War II. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0817300180.

- White, Gerald T. "Financing Industrial Expansion for War: The Origin of the Defense Plant Corporation Leases" Journal of Economic History 9#2 (1949), pp. 156–183 online

External links

- Guide to the Jesse H. Jones Family and Personal Papers, 1841-2000 (Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Houston, Texas)