Zhaagobe (c.1794), also known as Jack-O-Pa or Shagobai, was a St. Croix Ojibwe chief of the Snake River band. He signed several Chippewa treaties with the United States, including the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien, the 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac, the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters, and the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe. In 1836, geographer Joseph Nicollet had an Ojibwe guide he called Chagobay (or "Little Six"), but historians are uncertain as to whether they were the same person.

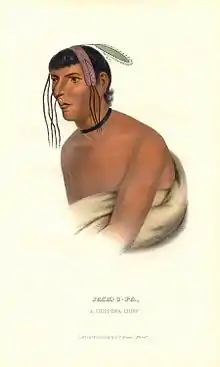

Chief Zhaagobe's portrait, painted by Charles Bird King, appears in History of the Indian Tribes of North America under the name "Jack-O-Pa – The Six".[1]

Joseph Nicollet's guide

An Ojibwe man called Chagobay served as a guide to French geographer Joseph Nicollet during his expedition to the upper Mississippi River in 1836. However, historian Martha Coleman Bray states that there is no clear evidence that the Snake River chief and Nicollet's guide are the same person.[2]

Zhaagobe was the Ojibwe translation of the name "Six." In his journal, explorer Joseph Nicollet refers to his guide as "Chagobay," "Shago-bai," or "Little Six."[2]

In 1836, Chagobay accompanied Nicollet as far as Leech Lake, together with his ten-year-old son. They left Saint Anthony Falls on July 29, 1836, together with Nicollet's half-French guide Brunia. On the first day, they encountered a large flotilla of Sioux canoes returning from a raid against the Chippewa. Nicollet identified the Sioux war party as having come from Lake Calhoun (now known as Bde Maka Ska) and from the village of Shakopee, near present-day Shakopee, Minnesota.[2]

Chagobay provided Nicollet with details on the upper Mississippi and its tributaries, such as Rice Creek near Fridley, Minnesota; Coon Creek; Elm Creek (near Rum River); and Wolf Creek and Rocky Creek. During the journey, Chagobay also taught Brunia about how to recognize constellations of stars in the night sky.[2]

In addition, Chagobay revealed the secrets of the medicine ceremony to Nicollet, at some risk to himself. On September 29, 1836, Nicollet noted that a ceremony had been held to absolve Chagobay of his guilt for revealing these secrets. The ceremony was conducted by Flat Mouth.[2]

Letter to Nicollet

Joseph Nicollet developed a close friendship with Chagobay. The following letter dated May 19, 1837 was dictated by Chagobay to missionary William Thurston Boutwell:[2]

Friend Nicolette:

Little Six wishes me to write a line for him. "My friend I think of you so much. I shake hands with you. I send these bear claws which I take from my heart that you may remember me. When I was young I loved what I send you. When I was young I dreamed, if I kept this little animal's skin I should live long, and now I send it to you that you may remember me. We will be friends while we live and meet in that good place and be friends after we die. I wish you to send me another shell by Brunette such as you gave me last fall. Write me by Brunette that I may hear from you yourself. I am afraid I shall not be able to pay my credit if I don't hunt this spring or else I would come and see you before you leave.

The last time I saw you I was poor. I am still poor now. I have not tobacco to fill my pipe.

I shall still look for what you promised me in a small box."

— Shâgobe, his mark X[2]

Nicollet sent Chagobay some tobacco and a letter in reply, which was written in English. The handwriting has been identified as most likely belonging to Henry Hastings Sibley, whom Nicollet was staying with in Saint Peters (Mendota).[2]

Treaties

Several treaties with the United States were signed by a Chippewa chief named Zhaagobe or "Six."

Treaty of Prairie du Chien, 1825

The 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien was signed by chiefs and headmen from tribes including the Dakota Sioux, the Ojibwe, the Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox), the Menomonee, the Iowa, the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), and the Odawa.[3]

The Dakota chief Shakopee made his mark on the treaty in the section under "Sioux," where he is listed as "Sha-co-pe (the Sixth)." Under the section for "Chippewa," there is a separate listing for a signatory named simply as "The-sees"[4] which suggests the French pronunciation for "Six."

Treaty of Fond du Lac, 1826

The 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac attempted to bring all Ojibwe bands into agreement with the United States, as some had not been present at the signing of the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The previous treaty had established boundary lines between tribes and promised intertribal peace.

The 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac affirmed that all Ojibwe bands would adhere to the terms of the 1825 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. In addition, the Fond du Lac treaty granted the United States the right to search for minerals and mine in Ojibwe lands near Lake Superior.[5] One of the Ojibwe signatories from the River St. Croix was recorded as "Chaucopee."[6]

White Pine Treaty, 1837

In the 1837 Treaty of St. Peters, also known as the White Pine Treaty, the Ojibwe traded most of their lands in present-day Wisconsin to the United States for a twenty-year annuity plus other compensation.[7] Evidence suggests that the Ojibwe negotiators believed that they were merely leasing use of the pine forests to the U.S. to cut timber.[8] One of the treaty signatories from the Snake River band was listed as "Sha-go-bai" or "the Little Six."[9]

Treaty of La Pointe, 1842

The 1842 Treaty of La Pointe was negotiated between the United States and the Ojibwe of Wisconsin on Madeline Island. The treaty ceded the last of the Ojibwe lands in northern Wisconsin and part of the Upper Peninsula to the United States, in return for cash, goods and other compensation every year for 25 years.[7] One of the signatories was "Sha go bi," first chief of the Snake River Ojibwe.[10]

Refusal to part with son

Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas L. McKenney described Chippewa chief "Jack-O-Pa" as "an exceedingly active, sprightly fellow quick in his movements, ardent, and fond of his family."[1]

In the History of the Indian Tribes of North America, the authors note that at the signing of the 1826 Treaty of Fond du Lac, McKenney had offered to take Jack-O-Pa's fourteen-year-old son back to Washington to educate him, but that the chief had declined:[1]

Jack-O-Pa looked awhile and shaking his head, run his finger from his forehead downwards indicating that to part from his boy, would be like cutting him in two.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 McKenney, Thomas L.; Hall, James (1836). Catalogue of one hundred and seventeen Indian portraits, representing eighteen different tribes. p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Nicollet, Joseph N. (1970). Bray, Martha Coleman (ed.). The journals of Joseph N. Nicollet: a scientist on the Mississippi headwaters, with notes on Indian life, 1836-37. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 19, 31, 44. ISBN 0873510623.

- ↑ Holcombe, Return Ira (1908). Minnesota in Three Centuries. Vol. 2. New York: The Publishing Society of Minnesota. pp. 271–272, 273–274, 277.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. (1904). "Treaty with the Sioux, etc., 1825". Indian Affairs: Laws and treaties, Vol. 2 (Treaties). Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 254–255.

- ↑ "U.S. Treaties with the Ojibwe or Chippewa of the Fond du Lac region". Onigamiinsing Dibaajimowinan – Duluth's Stories. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. (1904). "Treaty with the Chippewa, 1826". Indian affairs: laws and treaties, Vol. 2 (Treaties). Government Printing Office. p. 270.

- 1 2 "Ojibwe Treaty Rights". Milwaukee Public Museum. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ↑ "1837 Land Cession Treaties with the Ojibwe & Dakota". Relations: Dakota & Ojibwe Treaties. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. (1904). "Treaty with the Chippewa, 1837". Indian affairs: laws and treaties, Vol. 2 (Treaties). Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Kappler, Charles Joseph, ed. (1904). "Treaty with the Chippewa, 1842". Indian affairs: laws and treaties, Vol. 2 (Treaties). Government Printing Office. p. 544.