A monument of the Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi in the capital city of Montevideo. He is considered by many as an important contributor towards the independence of Uruguay. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 90,000 (by birth)[1] c. 1,500,000 (by ancestry, about 44% of the total Uruguayan population)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Uruguay, principally found within Montevideo. Numbers are also found in the southern and western departments. | |

| Languages | |

| Uruguayan Spanish · Rioplatense Spanish · Italian and Italian dialects | |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Italians, Italian Americans, Italian Argentines, Italian Bolivians, Italian Brazilians, Italian Canadians, Italian Chileans, Italian Colombians, Italian Costa Ricans, Italian Cubans, Italian Dominicans, Italian Ecuadorians, Italian Guatemalans, Italian Haitians, Italian Hondurans, Italian Mexicans, Italian Panamanians, Italian Paraguayans, Italian Peruvians, Italian Puerto Ricans, Italian Salvadorans, Italian Venezuelans |

Italian Uruguayans (Italian: italo-uruguaiani; Spanish: ítalo-uruguayos) are Uruguayan-born citizens who are fully or partially of Italian descent, whose ancestors were Italians who emigrated to Uruguay during the Italian diaspora, or Italian-born people in Uruguay. Outside of Italy, Uruguay has one of the highest percentages of Italians in the world. It is estimated that about 44% of the total population of Uruguay are of Italian descent, corresponding to about 1,500,000 people,[2] while there were around 90,000 Italian citizens in Uruguay.[1]

Italian community

Outside of Italy, Uruguay has one of the highest percentages of Italians in the world. An estimated 1,500,000 Uruguayans have Italian ancestry, about 44% of the total population of Uruguay.[2] Italian immigration to Uruguay refers to one of the largest migratory movements Uruguay has received. The population of Italian origin, together with that of Spanish origin, forms the backbone of Uruguayan society.[3][4][5] Uruguayan culture bears important similarities to Italian culture in terms of language, customs and traditions.[6] Italian emigrants began to arrive in Uruguay in large numbers in the 1840s and this migratory flow continued until the 1960s.[7][6]

History

In 1527 Venetian explorer Sebastiano Caboto founded San Lázaro, the first European settlement on the Río de la Plata.[8][9][10] The first Italians arrived in the Spanish colony in the 16th century. These were, mainly, Ligurians from the Republic of Genoa, who worked on transoceanic merchant ships.[11] The first inhabitant of Montevideo was the Genoese Giorgio Borghese (who Hispanicized his name to Jorge Burgues), who built a stone house on a ranch where he raised cattle before the city was founded.[12] Sailing in the service of the Spanish crown, the Tuscan sailor Alessandro Malaspina undertook a scientific voyage known as the Malaspina Expedition, which led him to explore the coasts of Montevideo in 1789. On board two corvettes traveled botanists, zoologists, draftsmen, doctors, dissectors, geographers, astronomers and hydrographers, whose objectives were to carry out a cartography of the Río de la Plata and observe astronomical phenomena.[13][14]

Already in the 19th century relations began between Uruguay and the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, which signed some commercial and navigation treaties.[15] After the revolutions of 1820 and of 1830 in Italy, some revolutionaries fled to America from Piedmont, the Papal States and the regions of Southern Italy.[16] The number of immigrants began to increase starting from 1830, after the obstacles imposed on immigration that were in place during the colonial era were eliminated:[17] this also coincided with the political situation in Argentina, which prevented immigration.[18]

In 1835, 2,000 citizens of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia resided in Montevideo and two years later, over 2,500 Italians were registered.[19] These first immigrants were found on the outskirts of Montevideo and were, for the most part, Piedmontese peasants, who arrived in a Uruguay at that time without industrial development, with extensive farming but little agricultural exploitation. Around the year 1842 it was estimated that the colony consisted of 7,945 Italians, with a prevalence of Lombards, dedicated to agriculture or domestic services, and also counting on the presence of Genoese sailors who dealt with the trade of Italian goods.[18][20] Around the year 1843, Italians were 25% of the immigrants in Uruguay, behind the French and the Spanish.[21]

Subsequently a significant number of colonists arrived from Sardinia and during the Uruguayan Civil War several Italians participated in the defense of the region led by Giuseppe Garibaldi.[17] To join the ranks of Garibaldi's Italian Legion, in January 1851, about 100 Italian volunteer ex-military officers and a minority of Ticino and Hungarians embarked from Genoa.[22] In recognition, many tributes were paid to the memory of Giuseppe Garibaldi, including an avenue named after him and monuments in Montevideo and Salto.[23][24] The migratory trend began to change starting from the Uruguayan Civil War, when the Italians, together with the Spaniards, were the first in terms of number of immigrants.[21]

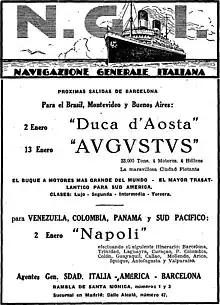

The main ports of departure were located in Genoa, Savona, Livorno, Palermo and Naples. After the unification of Italy in 1861, starting from 1865 there was an increase in the arrival of Italians, facilitated by the laws established in the years 1853 and 1858 which favored immigration to Uruguay.[17] Some immigrants were the product of migratory movements that had previously occurred in Europe, as in the case of citizens of Italian origin born in Gibraltar, children or grandchildren of Ligurians.[25] It was in the early 1860s that the number of immigrants began to grow, mostly from Liguria, Lombardy and Piedmont, and subsequently the arrival of workers from the south of the peninsula, mainly from Basilicata and Campania.[15] During this period, immigration increased year over year without interruption.[26]

In the second half of the 19th century, Uruguay experienced the highest percentage of demographic growth in South America where the country's population multiplied almost sevenfold between 1850 and 1900, due to immigration, mostly Italian.[27] The Argentine historian Fernando Devoto identified the third quarter of the 19th century as the "golden age of Italian emigration to Uruguay".[28]

In 1887, Italians were between 20% and 30% of the total population of Montevideo.[18] It was during this decade that the boom in Italian immigration to Uruguay took place and the first attempts were made by both countries to encourage the arrival of immigrants.[22] The "Taddei contract" was signed between Italy and Uruguay, which provided for the transfer to the South American country of between 2,000 and 3,000 Italian families, mainly farmers and day laborers of Lombard origin.[29][30] The arrival of Italians continued to be stimulated through consular announcements.[31] The greatest entry of Italians into Uruguay occurred between 1880 and 1890, when 60% of the total arrived.[20][32] An 1889 census indicated that half of the population of Montevideo was born in Uruguay and Italians were almost half of the foreign population.[33]

However, around the year 1890 there was an economic crisis in Uruguay which conditioned the entry of immigrants.[34] The country took restrictive measures on immigration, such as the elimination of the Commissioner-General for Immigration, who was in charge of housing, food and work for new arrivals.[35] These conditions have diverted a large part of the migratory flow of Italians towards Argentina.[34] In the period from 1880 to 1916, 153,554 immigrants arrived in the South American country, of whom 66,992 (43.63%) were Italians and 62,466 (40.68%) were Spanish.[36] With the Italian entry into World War I, the migratory flow decreased and some Italians residing in Uruguay also enlisted.[15] On 11 November 1918, Uruguay celebrated the signing of the armistice which marked the end of the war.[15] As the Uruguayan minister to Italy Manuel Bernardez stated after the war, among the countries of America "in none as in Uruguay does the Italian spirit flourish with such pride" and he added that "of the Italian war loans, Uruguay was the South American nation which subscribed the highest percentages per capita".[37] The optimal relations between the two countries in that period increased with the arrival to the presidency in 1922 of José Serrato, the 70-year-old son of an Italian immigrant and the Minister of Foreign Affairs Pedro Manini. In 1923, the "Convention for the Abolition of Visa Passports" was signed.[15] With the rise of fascism in Italy, the number of emigrants at the port of Montevideo was not remarkable; in the 1920s, only 18,830 Italian immigrants arrived in Uruguay.[38] Further, around 1938 a certain number of Italian Jews came to Uruguay, feeling rejected in their mother country by the anti-Semitic racial laws.[39]

Alfredo Baldomir Ferrari — of Italian origin — was president of Uruguay from 1938 to 1943.[41] At the beginning of the World War II, Uruguay — hitherto neutral — broke off diplomatic, commercial and financial relations with Italy and with Axis countries in January 1942, shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor.[15] The Italian language acquired considerable importance in Uruguay in those years, in 1942, under the presidency of Baldomir Ferrari, and its study became compulsory in high schools.[41] Due to the excess rural population, the lack of employment and the hardships caused by the war, the migratory flow of Italians to Uruguay resumed.[42] In 1952 an agreement on emigration was signed in Rome for the first time between the two countries with the aim of "increase and regulate it" taking into account the demand for manpower in Uruguay and the manpower available in Italy, mainly to cover needs.[43] Italian workers had the same rights as Uruguayans and the Uruguayan government took care of their accommodation and maintenance up to 15 days after their disembarkation.[44][45]

Historian Juan Oddone defined the period between 1930 and 1955 as a phase of "late immigration". After the end of World War II, this migration was characterized by the arrival of skilled immigrants, mostly from Sicily and Calabria. Already in the 1960s the migratory flow stopped and Uruguay passed from a host country to a country of emigrants.[46]

Characteristics

.jpg.webp)

Already in 1815, the city of Carmelo had the presence of Italian immigrants, who continued to arrive in large numbers in the decades to come.[49] In 1855, a process of colonization began to develop in the agricultural areas of Carmelo, where Italian and French families founded Colonia Estrella, a community whose population was made up of 80% of Italians.[50] According to a 2018 newspaper article, 60% of Carmelo's population had Italian ancestry.[49] In 1858, the Waldensians from the rural areas of Piedmont founded Colonia Valdense, and this community remained ethnically and culturally homogeneous for decades until the 1960s, when the area began to become urbanised.[51] In mid-1883, the city of Nico Pérez was founded, which counted immigrants from the Italian peninsula among its first inhabitants.[50] Between the years 1879 and 1891 the company of Francisco Piria La Comercial was born, hence the name of the district, where, on the outskirts of Montevideo, plots of land were divided up and sold, which were mostly occupied by Italian immigrant workers. This area was divided into small neighborhoods bearing Italian names such as Caprera, Vittorio Emanuele II (from the name of the homonymous king of Italy), Nuevo Génova, Garibaldino, Nueva Roma, Nueva Savona, Nuova Napoli, Degli Italiani, Bella Italia, Umberto I (from the name of the homonymous king of Italy) or Italiano. The streets were also named after Italian figures, and busts of members of the House of Savoy or of Giuseppe Garibaldi could be seen in the squares.[52] For example, the Umberto I neighbourhood was built in 1890 between the Unión and Buceo districts by Italian immigrants. Its streets evoked protagonists of the unification of Italy such as Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Giuseppe Mazzini or Massimo d'Azeglio.[53]

In the first half of the 19th century, Giuseppe Garibaldi was a participant in Uruguay's wars for independence, and many Italian patriots in Uruguay were attracted to the ideas of the leader. The political movement which joined many residents of the Rio de la Plata with Italian was called Current Garibaldina. In recognition of Garibaldi are many tributes to his memory such as a "Avenida" (Course) of Montevideo with its name, a monument to his memory in the city of Salto, and el 'Italian Hospital of Buenos Aires.

According to the national census of 1860, excluding the departments of Paysandú and Maldonado, 76% of Italians resided in the Montevideo Department, and they were 13% of the total population of the capital. The Italian community recorded greater urbanization than other groups such as those born in the country or the Spaniards where only 43.7% lived in the capital, who were more dispersed among the other departments of the territory.[54] Italians were distributed throughout Montevideo and reached significant percentages of the total population of areas such as Cerrito de la Victoria (21%), Peñarol (20.5%) and Cordón (17%). The areas with the greatest concentration were Ciudad Vieja and Centro, where respectively 39% and 25% of all Italians in the areas lived.[55] The Palermo district took its name from the Sicilian city of the same name due to a sign with the inscription "Drogheria della Nuova Città di Palermo", owned by Sicilian immigrants. One of the first mentions of the neighborhood with that name on the map of Montevideo dates back to 1862.[56] In the following decades, most of the Italian immigrants will continue to settle in Montevideo. In 1900, 39.40% of them lived in the capital and in 1908 the percentage had risen to 42.74%.[57]

| Year | Montevideo1 | West area2 | Central area3 | East area4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 74.27 % | 14.63 % | 8.46 % | 2.64 % |

| 1879 | 37.47 % | 24.88 % | 23.69 % | 13.95 % |

| 1908 | 64.31 % | 17 % | 14.41 % | 4.28 % |

| 1 Montevideo Department. 2 Colonia Department, Soriano Department, Río Negro Department, Paysandú Department, Salto Department and Artigas Department. It is unknown the number of Italian immigrants residing in Paysandú Department and Río Negro Department in the year 1860. | ||||

In the 1880s, the Italian community in the Florida Department numbered 940, 4.5% of the department's population. The Italian presence was more significant in the city, where towards the end of the century the urban center had a neighborhood called the "Italian quarter" made up mostly of Italian workers.[59] The rural area with the highest concentration of Italians was Canelones which reached 5,700 immigrants in 1891.[60][61] In 1893,[62] Francisco Piria founded the spa town of Piriápolis taking as a model the Ligurian town of Diano Marina, the city where Piria had studied from six to thirteen years.[63] Both cities twinned in 2014.[64] Others of the most numerous communities around 1900 were established in Colonia (3,900), Paysandú (3,600) and Salto (2,300).[61]

Regions of origin and occupation

Data from the 1850s indicates that nearly 30% of Italian men in Montevideo were engaged in trade, 45% were artisans or self-employed, and 22.2% were employed.[66] In 1860, Ciudad Vieja was the commercial and political center of the country. It has been estimated that 33% of Italian workers carried out non-manual activities (mainly in commerce), 30% were engaged in skilled manual work and 19% in unskilled work; although the registers contained no information on the regions of origin of those immigrants, Ligurian surnames predominated.[55] Likewise, an Italian consul of the time stated that of the captains, sailors, carpenters and other port workers "almost all belong to one or other of the Ligurian coasts".[65] A census of Italians abroad carried out in 1871 confirmed that the largest regional group was the Ligurian one and that most of them were still in Montevideo. In the city of Colonia del Sacramento, 14% engaged in agriculture, while the rest remained in urban areas where the most popular jobs were bricklayers and carpenters; only 10.4% came from southern Italy.[67]

Until the 1870s Ligurian immigration had prevailed and Uruguay had received a number of immigrants similar to Argentina and higher than Brazil, however, with the massive arrival of Italians that occurred since then, Liguria ceased to be the main region of origin of the immigrants and the arrival of these was distributed among other South American nations.[69] The regions of origin of the Italians diversified and artisans, decorators and painters arrived from Emilia-Romagna and the Marche. The first sculptors of funerary art arrived from Tuscany and peasants arrived from Piedmont to live in the interior of the country as farmers, shepherds or woodcutters. Other of the more common occupations they held in the capital were peddler of bric-a-brac, fruit or vegetables, tinsmith, charcoal burner, garbage man, shoe shiner, and accordion player.[70] According to data for 1885, about 60% of the immigrants came from the north of the Italian peninsula. The majority, 32%, had emigrated from Liguria, while 28% came from the southern regions, 14% from Lombardy, 10% from Piedmont, 4% from Veneto, South Tyrol and Friuli and 12% from other regions.[68] Between 1854 and 1863, of the 47,000 emigrants who left Liguria, more than 31,000 headed for South America.[71] However, of the Italians who landed between 1882 and 1886, 53% came from the southern regions or islands. While the Ligurians, who had settled in the capital for the longest time, tended to monopolize small and large businesses, the Southerners carried out jobs such as shoemakers, unskilled workers, fruit peddlers, shoe shiners or labourers.[72] In 1889, a census of industry in Montevideo was carried out, indicating that of the 2,355 industries registered in the department, 45.5%, or 1,072 establishments, many of them modest artisan offices, were owned by Italians.[73]

Although no national censuses were carried out in the last 20 years of the 19th century, data on Italians in Montevideo were collected. In 1884 they were 32,829 (20% of the total population), and in 1889 they were 46,991 (22%).[74] Starting in 1890, the migratory current began to consist mostly of immigrants from southern regions and islands, a trend that continued until the 1920s.[75] A 1906 survey carried out by the Italian colony of Salto showed that the 59.86% came from northern Italy, 19.10% from the center and 17.10% from the south. In a similar survey also carried out in Salto to highlight the employment trend, it emerged that 35% of the interviewees were engaged in commerce, 25% in agriculture, 28% in industry and crafts, and the 12% held other jobs. Among the northern Italians the majority were merchants (50%) and farmers (19%), numbers similar to those of central Italy which were mostly farmers (50%), shop assistants (25%) and merchants (21%). In contrast, immigrants from the south were artisans (56%), traders (22%) and farmers (15%).[76] After their arrival at the port of Montevideo at the beginning of the 20th century, the workers most in demand were day laborers, craftsmen, seamstresses, cooks, masons, carpenters and shoemakers.[77] During the last decade of the 19th century, the tendency for Italians was to earn a living by carrying out a trade, trading and working independently. Furthermore, a large number of Italians invested their savings in building their own houses and buying land.[78]

Discrimination and assimilation

During Uruguay's industrialization process and the massive arrival of immigrants in the country, some sectors of local society did not look kindly on Italians. While the French and the British were considered "advanced", there was a rejection of the Italians due to cultural differences, humble origins or the lack of economic success of some. Thus were born derogatory terms such as "tano", "gringo", "bachicha", "musolino", "goruta" or "yacumino" to refer to Italian immigrants. The rejection was not only experienced in the city; the arrival of Italian workers in the countryside was perceived as an "invasion" by the Creoles who settled there, which led to violence and even the murder of immigrants.[80]

In the 20th century, the negative perception of Italians by Creole society began to disappear. For Juan Oddone, "the resistance to the immigrant and the rejection of his immediate vision of the world began to decrease with his gradual economic and social imposition" and "these changes accelerated when the first generations of Uruguayans of Italian origin began the process of social ascent".[80] Some factors that favored the cultural assimilation of Italian immigrants were mixed marriages and access to primary education. Thus there was a "creolisation" of the Italians, who imitated the customs, behaviour, eating habits and language of the local population.[81]

However, in other periods, such as after the World War II, the Italian spirit strengthened.[81] After the cultural clash between the first wave of immigrants and the Creole society, many traditional Italian traits were adopted by the Uruguayan population, producing an "Italianization" and favoring easier integration of immigrants who arrived later.[82] The newspaper La Mañana highlighted the important Italian influence in the history, ethnicity, character and culture of Uruguay, and stated that "it is difficult to find an aspect of Uruguayan society in which the legacy of Italian culture cannot be traced".[83]

Culture

Italian immigration has influenced Uruguayan culture, mainly in language, gastronomy, architecture, religion and music. Anthropologist Renzo Pi Hugarte stated that the Italian presence in Uruguay "has left deep marks in its popular culture, to the point that the elements that have come to distinguish it are generally perceived as originating in these places and not as adaptations of Italic models".[6]

Language

The first Italian immigrants who arrived in Uruguay in the second half of the 19th century spoke the regional language or local dialect of their region of origin.[84] It was with the unification of Italy in 1861 that the use of a common language, the Italian language, began to spread throughout the Uruguayan territory.[85] The integration of these immigrants into Uruguayan social life was facilitated by their linguistic proximity to the Spanish language. The preservation of Italian as a mother tongue, over time, has depended on various factors such as age, family composition, cultural level, type of work performed, ties with the mother country or traditions.[84] Since independence, the Uruguayan state has engineered a linguistically homogeneous country, and its Spanish literacy policies have discouraged bilingualism.[86] Studies carried out by the University of the Republic of Uruguay indicated that Italian immigrants used their mother tongue, but their spoken language was influenced by Spanish, while the next generation — born in Uruguay — learned Italian at home, but this did not interfere with the use of Spanish and finally the third generation no longer spoke the Italian or the dialect of their ancestors but only spoke Spanish. These investigations also suggested that the Italian language was lost faster in Uruguay than in other places, such as New York City, as Italians in Uruguay were more easily assimilated.[87][88]

The Waldensian immigration to the Colonia Department brought with them patois, which, although it had been replaced by Spanish over the generations, was to be preserved as an "ethnic language".[89] Accompanying the migratory flow that came from Italy, priests also arrived; While some of them used Italian to preach, others have also offered their services in Spanish over time. Latin was used by Salesian priests around 1880, a practice which was abandoned due to its dissonance with the local language.[90] The Italian emigrants who landed during World War II tended to have a higher level of education than in the first wave of migration and in comparison spoke a more formal Italian, being able to differentiate it from Spanish and avoiding linguistic mixtures.[91] Besides speaking their regional dialects, they had some knowledge of standard Italian. This is the case with the Waldenses, who spoke patois, French and, to a lesser extent, Italian.[92] This was related to the situation in Italy, where standard Italian was establishing itself as the common language of all social classes and the use of dialects was gradually being lost. Although the diffusion of standard Italian was increasing, its use was not yet fully established and an informal and colloquial version of it, popular Italian, had not yet developed, so immigrants created their own variety of popular Italian outside the Italian language of origin, when they were forced to actually use that language in informal oral interactions with Italians of other regional origins.[93]

From the linguistic mixing between the Italian dialects and Spanish, cocoliche was born, a slang spoken in the tenements of the Italian immigrants of the Río de la Plata in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[94] Author Carol A. Klee has indicated that "cocoliche was spoken only by native Italian speakers who were in the process of acquiring Spanish and were not passing it on to their children."[95] Similarly, the writers José Gobello and Marcelo Oliveri stated that "the first effort to make oneself understood led to cocolic, a transitional language. Immigrants spoke it. The second effort to learn Spanish, that of the children of immigrants, led to lunfardo".[94] Emerging in the popular neighborhoods of the Río de la Plata during the second half of the 19th century,[95] Lunfardo was another slang that combined Spanish with words of foreign origin, mostly coming from Italian dialects.[96] Over the years the use of some Lunfardo terms spread to the higher social classes who previously rejected the slang.[97] The origin of the word "lunfardo" is not certain, but it is hypothesized that it may derive from "Lombard".[98][99] Italian immigration greatly influenced the Spanish of the Rio de la Plata, so much so that it became the variant of Spanish with the most Italianisms.[100] Words of Italian root such as "chau", "guarda", "atenti", "minga", "facha" or "gamba" became part of the Rio Plateans vocabulary; also diminutive or pejorative suffixes were added.[101]

Architecture

Along with the demographic expansion that Uruguay was experiencing, the construction industry flourished between the 1880s and 1920s in the Río de la Plata area, influenced by Italian and French architecture.[102] The work of Italian builders and architects in that period was to determine the characteristic architectural style of Uruguay,[103] which responded to currents such as eclecticism and historicism, with characteristics of the Italian Renaissance to which then, at the beginning of the 20th, some Italian modernist architectural motifs were added.[102][104] It was not just a question of transplanted Italian models, but from them the techniques were adapted to the new territory.[103] The buildings of the time maintained an aesthetic harmony in every neighborhood and at the same time each architectural work kept its own characteristics,[103][104] paying particular attention to the aesthetic aspect both in the design of public buildings and private residences.[102] This consistency has been maintained despite the passage of time, when houses were built with more or less decoration, size or value.[105]

At that time Italian immigration was vital to the architectural development of the city, and it was also the largest foreign community in the construction sector; for every Spanish worker there were four Italian workers.[106] Most of the builders who built the projects were Italian immigrants.[107] They also made up the bulk of the highly skilled workforce.[108] They were even more numerous in handicraft jobs and related to the artistic or decorative side of architecture, such as mosaicist, tiler, woodworker, marble, portland plasterer, glass engraver, marble worker, designer or painter. Due to the Italian intervention, there was talk in the region of "Italian houses" to refer to certain buildings of the time.[109][110]

Cuisine

.jpg.webp)

Uruguayan eating habits are heavily influenced by Italian cuisine, which has adapted to its new environment and merged with other culinary uses found in the country.[111] Italian immigrants introduced some foods to Uruguay that began to be consumed frequently by the Uruguayan population, such as pasta, polenta, cotoletta, farinata and pizza.[112][113][114][115] The types of pasta most consumed in Uruguay are tagliolini, ravioli, spaghetti, vermicelli, cappelletti and tortellini.[111][116][117] The Italian presence in Uruguay has generated the development of traditions unknown in Italy, such as the consumption of pasta on Sundays or the gnocchi on the 29th of each month.[118][119]

The noquis del 29 ("gnocchi of 29") defines the widespread custom in some South American countries of eating a plate of gnocchi, a type of Italian pasta, on the 29th of each month. The custom is widespread especially in the states of the Southern Cone such as Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay;[120][121][122] these countries being recipients of a considerable Italian immigration between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. There is a ritual that accompanies lunch with gnocchi, namely putting money under the plate which symbolizes the desire for new gifts. It is also customary to leave a banknote or coin under the plate to attract luck and prosperity to the dinner.[123]

The tradition of serving gnocchi on the 29th of each month stems from a legend based on the story of Saint Pantaleon, a young doctor from Nicomedia who, after converting to Christianity, made a pilgrimage through northern Italy. There, Pantaleon practiced miraculous cures for which he was canonized. According to legend, on one occasion when he asked Venetian peasants for bread, they invited him to share their poor table.[124] In gratitude, Pantaleon announced a year of excellent fishing and excellent harvests. That episode occurred on 29 July, and for this reason that day is remembered with a simple meal represented by gnocchi.[123]

A typical creation of Italian-Uruguayan cuisine is cappelletti with Caruso sauce, a dish that originated in a well-known pasta restaurant called Mario y Alberto. In 1954, to accompany the cappelletti, the Piedmontese chef Raimondo Monti combined cream, cooked ham, mushrooms sautéed in lard and a spoonful of meat extract to create the Caruso sauce, in honor of the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso.[125] While in Italy most of the dry pasta is consumed, in Uruguay the consumption is divided between dry and fresh pasta.[111][126] Thus the "pasta factories" proliferated in the countryside of the Rio de la Plata, places for the preparation and sale of fresh pasta.[127] One of the traditional pasta factories in the town was La Spezia, active from 1938 to 2017, founded by the Bonfiglio brothers, originally from Manarola (province of La Spezia, Liguria, Italy).[128][129][130]

In the 19th century, immigrants from Liguria and Campania respectively introduced farinata and pizza to Uruguay. At the end of that century, the Italians began to devote themselves to itinerant sales and opened the first pizzerias with a wood-burning oven.[131][132] Uruguayan variants emerged from the Neapolitan pizza, such as the "pizza al tacho", made with various cheeses and without tomatoes, made by the Italian pizza maker Angelo Nari at the Bar Tasende in Montevideo in 1931.[131][133] In 1915, the Guidos, two Piedmontese brothers, founded the first mill for the production of the flour for the farinata.[134][135] The farinata — originally from Liguria and also known in Piedmont and Tuscany — was more widespread and rooted in Uruguay than in Italy.[131] Another of the most important dishes of Uruguayan gastronomy is the chivito, a sandwich with beef tenderloin and other ingredients that is accompanied by french fries.[136][137][138] The chivito was born in 1946 in a restaurant in Punta del Este called El Mejillón when an Argentine woman asked for a plate of goat meat and, given the lack of this type of meat, the owner and chef of the restaurant Antonio Carbonaro - of Calabrian parents from Siderno - made a sandwich with fillet meat, ham and spread with butter. Later other ingredients such as lettuce, tomato and eggs would be added. Since then the dish began to gain more and more popularity.[139][140]

During World War I, Genoese fishermen introduced ciuppin, a fish and shellfish soup that was eaten on boats, into Uruguay. Fishermen also brought the recipe to other parts of the world such as California, where it adopted the cioppino name and became part of Italian-American cuisine. In Montevideo it was one of the most popular dishes in the early 20th century and, as in the United States, it was also adapted to local customs, in this case by including corvina and marine catfish.[141] Other Italian foods that became part of Uruguayan cuisine are Lombard busecca, torte fritta, polpette, and Ligurian torta pasqualina.[142][143][144][145] Sweet foods such as pastafrola, panettone and massini, a dessert originally from Italy but which has become popular in Uruguay, also arrived in Uruguay.[146][147][148][149] At the beginning of the 1900s, the marketing of gelato also began; one of the first gelato shops was the Heladería Napolitana, located in front of the Plaza Independencia in Montevideo.[150] In 1938, the Salvino Soleri family arrived in Montevideo and opened Los Trovadores, an artisanal gelato shop that stood out for its gelato with flavors such as zabaione and melon.[151] Subsequently, the Barcella family of Trescore Balneario in Lombardy settled in Punta del Este and in 1998 opened the Arlecchino gelato shop. The Arlecchino gelato shop has been well received by both the local public and tourists, maintaining an elaboration based on the origins of gelato in Italy — importing some products such as almonds or pistachios — and at the same time adapting to the customs of the Uruguayan public, including flavors such as the dulce de leche.[151][152]

Italian immigration also boosted the production of wine in the country, when small family businesses dedicated to viticulture were established starting in the 20th century.[153][154] In 1871 the Italian Federico Carrara was successfully producing wine from the Piedmontese Barbera and Nebbiolo vines.[155] Buonaventura Caviglia arrived in Montevideo from Castel Vittorio (Liguria) in 1868 at the age of 21, an important entrepreneur and businessman who during the 1890s began to found various agro-industries to devote to the production of wine in the municipality of Mercedes from where it expanded and became the largest producer in the area.[156] An 1888 survey found that most winegrowers were Italians or sons of Italians.[157] In Uruguay, between 1960 and 1970, wines were produced from Nebbiolo and Sangiovese grapes, widespread in the center of the Italian peninsula.[158] Another typical Italian drink introduced in the country was grappa, and from its mixture with honey grappamiel was born in Uruguay.[159][160]

Sport

The name of one of the two most important football teams in Uruguay, the Peñarol (the other is the Club Nacional de Football), comes from the deformation of Pinerolo, the town of origin of Giovanni Battista Crosa, Spanishized as Juan Bautista Crosa, a Piedmontese immigrant.[161][162] Crosa arrived in Uruguay in 1765 where he set up a farm and later, on the same plot, he opened a grocery store called "El Penareul".[161][163] Due to the customs of the time it was common for the immigrants' country of origin to appear in the registry documents, thus Crosa began to appear as Crosa Pinerolo, later Spanishized as Crosa Peñarol. The area in which he had settled was renamed Villa Peñarol; Crosa died in 1790.[161] Another theory states that the name of the football club could derive from another Italian colonist, the farmer Pedro Pinerolo, who on his arrival in the town would have lost his original surname with the name of his hometown.[164][165] There is also another less important club that represented the Italian community, the Club Sportivo Italiano, which managed to play in the Uruguayan Segunda División.[166] Miguel Andreolo, originally from Salerno, also represented the Italy national football team and was world champion at the 1938 FIFA World Cup, also being included in the All-Star Team for the competition.[167][168][169] Andreolo's was the only case of a football player born in Uruguay and world champion with a national team other than that of Uruguay.[170]

Institutions

.jpg.webp)

The phenomenon of Italian institutions was born in the 19th century, developing above all during the 1880s.[171] In 1918, in Montevideo alone, there were 26 Italian associations, the oldest of which was the Società Reduci Patrie Battaglie, founded in 1878.[172] More patriotic associations were the Legionari Garibaldini in 1883, the Circolo Garibaldi and the Superstiti di San Antonio.[171] The largest number of Italian associations registered in the whole country dates back to 1897, when there were 72 associations, for a total of 11,400 members.[173] In the 19th century, the Italian Chamber of Commerce was also established, the first in the world.[5] Between 1883 and 1907 the Italian Bank of Uruguay operated.[174] In 1892, the Italian Hospital of Montevideo was inaugurated and the mutual aid society Operai italiani di Montevideo, which inaugurated an Italian school. Subsequently, the Italian schools of the Lombard League and the Circolo Napolitano were opened.[171] On the initiative of Leone Maria Morelli, these schools united to found the Scuola Italiana delle Società Riunite in 1886, which in 1918, was renamed the Scuola Italiana di Montevideo, which is still active today.[175] Other associations that served as a meeting point for the community had recreational purposes, such as the Casinò Italiano — in operation since 1880 — or the Circolo Italiano; others were oriented towards sport, such as the Italian Athletic Center, or towards music, such as the instrumental choral Lombard League or the Filodrammatica Choral School.[176] Subsequently, in 1906, the Mutual Aid Society, which had 1,906 members, and the Circolo Napolitano, with 1,421 members, were founded.[172]

The mutual aid societies that proliferated in the capital in the 19th century began to spread to other parts of the country; in particular in 1869 some were founded in San José de Mayo and Pando, and in the following years they reached Trinidad, Carmelo, Nueva Palmira, Rocha and Rivera.[171] Several Italian organizations were founded in Paysandú, the first of which was Unione e Benevolenza, founded in 1874 and which had a boys' primary school until 1885; there was also a Unione e Benevolenza Fermminile Society.[172] The XX Settembre society of Salto also opened an Italian school and for a time they operated schools in Rocha and Trinidad.[171] Currently there are also present in Paysandú Italian associations such as the Italian Cultural Center, as well as the specific cultural centers of each Italian region such as the Piedmontese Association, the Association of Sons of Tuscany, the Association Venetian in Uruguay, the Group of Lombard Paysandú, the Group Trentini Rivera, the Association of Lombards in Montevideo, the Lucan Association, the Ligurian Association, the Calabrian Association of Uruguay, the Campanian Association and the Neapolitan Club.[177][178][179] Overall, there are currently about 70 Italian organizations in Uruguay.[5] To spread Italian culture and the Italian language, the Dante Alighieri Society and the Istituto Italiano di Cultura settled in Montevideo.[180][181]

Italian-language media in Uruguay

Press

The important presence of Italian immigrants in Uruguayan territory gave rise to the written press in Italian language, which developed mainly from the mid-19th century to the 1940s.[182] L'Italiano, the first Italian-language newspaper in Uruguay, that was published weekly, appeared in 1841 and was founded by the Ligurian Giovanni Battista Cuneo, a pioneer of Italian journalism in South America and the first biographer of Giuseppe Garibaldi.[16] Despite being well received by Italian immigrants,[183] the Cuneo newspaper was last published on 10 September 1842 with number 23, due to lack of funds and collaborators.[184] In the 1880s, from the merger of L'Era italiana and L'Italia Nuova, a newspaper called L'Italia was born, whose journalist was Giovacchino Odicini, for whom an important journalist of the time reported that Odicini wrote «in the same way in language of Cervantes as in that of Boccaccio».[185][186] L'Italia became a point of reference for the Italian community in Uruguay.[185] Towards the end of the 19th century, the Italian community had the largest number of foreign-owned newspapers in Uruguay, concentrated in the capital, and the most circulated were L'Italia and L'Italia al Plata.[187][188] Towards the beginning of the 20th century, the Italian press also carried out its activity in other cities of the territory such as Salto, where 3,000 Italians lived, or Paysandú.[189] After the outbreak of World War I, a new stage of Italian journalism opened in Uruguay, with publications such as Il Bersagliere — also written in Spanish — which dedicated a large part of its content to the war, above all to the situation on the Italian front in Europe.[190] It was in this period that the first concerns about the future of the Italian press in Uruguay arose. According to the writer Pantaleone Sergi "the drop in the migratory flow and the almost complete assimilation of the old emigration" did not favor the situation of the immigrant press, observing that in the following years it had an ever smaller diffusion.[191] In the 1940s Italian journalism was characterized by the use of the radio instead of the press.[182] After the disappearance of L'Italiano in 1940, in 1946 no Italian newspaper was printed in Uruguay.[192] Finally, in 1949, the Messaggero italico, the first post-war newspaper, was published.[193] However, the press continued to be scarce and was slow to recover; between 1952 and 1955 Il Mattino d'America was published in Spanish and Italian, between 1956 and 1958 the Gazzetta d'Italia was published and between 1952 and 1954 the Annuario Aiufre was distributed.[194][195]

Currently the most important publications in Uruguay in Italian language are:

- L'Eco d'Italia ("The Echo of Italy"), weekly (Montevideo, since 1963), publisher Alessandro Cario;[196]

- Il Corriere della Scuola ("The School Courier"), quarterly (Montevideo, since 1989), editor Adriana Testoni (Scuola Italiana di Montevideo);[197]

- Spazio Italia ("Italy area"), monthly (Montevideo, since 1999), editor Laura Vera Righi (Italian Association of Legami Group).[198]

- La gente d'Italia ("The people of Italy"), newspaper (Montevideo, since 2005), publisher Porps International Inc. Editorial Group;[199]

Radio and television

In the mid-1950s Italian-language radio programs appeared in Uruguay. An important name in Italian radio journalism in Uruguay was Tullo Guiglia, from Mantua, who arrived in Montevideo in 1952 and who from 1954 hosted the information program Trenta Minuti con L'Italia, first on Radio Femenina, then on Radio Rural and finally on Radio Italia.[195] From 1958 to 1973, when he returned to Italy, Guiglia was in charge of the popular Italian music program La Voce d'Italia, which was also broadcast in Uruguay on CX 58 Radio Clarín. In 1963, still on Radio Clarín, the Sunday program La Voce dei Calabresi began to be broadcast.[200] Three years later, Radio Carve broadcast the program Hoy en Italia every Tuesday.[201]

In June 1966, the national public broadcasting company of Italy RAI arrived in Montevideo, whose Uruguayan office was inaugurated in the presence of representatives of both countries; its headquarters were located in the center of the capital on 18 de Julio Avenue. "RAI used presenters, actors and dubbers for its programs in Uruguay, who helped Italian Uruguayans not to lose their pronunciation of the Italian language," said Italian Uruguayan journalist Federico Guiglia.[200]

In the 1960s Canale 4 broadcast a program on Italian current events every fortnight, including shows, sports and interviews.[201] At the end of the 20th century La Voce dei calabresi was broadcast on CX 28 Radio Imparcial and new programs were broadcast such as Buongiorno dall'Italia on Radio Fénix CX40 and Spazio Italia on Radio Sarandí; there were also radio programs in other Uruguayan cities such as Tacuarembó, Salto and Paysandú.[202] Montevideo radio host Italo Colafranceschi also devoted himself to television, producing the programs Zoom Italiano, Italia Italia and Panorama italiano. The politician, journalist and architect Aldo Lamorte presented Italia ti chiama on the VTV channel, dealing with issues related to the Italian Uruguayan community.[203]

Notable Italian Uruguayans

The following list has well-known Uruguayans who are Italian citizens or have Italian ancestry:

Architecture and engineering

Art

- Orestes Acquarone, cartoonist and lithographer

- José Belloni, sculptor

- Alberto Breccia, cartoonist

- Juan José Calandria, painter and sculptor

- José Cuneo Perinetti, painter

- Pedro Figari, painter

- Antonio Frasconi, xylographist

- Giuseppe Maraschini, painter

- Virginia Patrone, painter

- José Cuneo Perinetti, painter

- Amalia Polleri, art critic

- Edmundo Prati, sculptor

- Luis Queirolo Repetto, painter

- Luis Alberto Solari, painter and engraver

- Eduardo Vernazza, painter

- Petrona Viera Garino, painter

- Cecilia Vignolo, sculptor and visual artist

Cinema

- Luca Barbareschi, actor

- Jorge Bolani, actor

- Rubén W. Cavallotti, film director

- Florencia Colucci, film actress

- Eduardo D'Angelo, film actor and comedian

- Mónica Farro, model and actress

- Juan Pablo Rebella, film director

- Jorge Temponi, actor

- Rina Massardi actress and film director

- María Noel Riccetto ballet dancer (black swan)

- Diego Delgrossi actor

- Guillermo Casanova film director

Economy

- Francisco Piria de Grossi, businessman

Literature

Music and Opera

- Francisco Canaro, violinist

- Mario Canaro, tango musician

- Abel Carlevaro, classic guitar composer

- Agustín Casanova, singer

- Maika Ceres, soprano singer

- Eduardo Fabini, composer

- Sergio Fachelli, singer

- Francisco Fattoruso, bass player

- Hugo Fattoruso, multi-instrumentalist and vocalist

- Osvaldo Fattoruso, musician

- Pablo Minoli, composer

- Julio Sosa (Julio María Sosa Venturini), tango singer

- Lucas Sugo (singer and songwriter)

- Luciana Mocchi, singer

- Los TNT, rock'n'roll band consisting of three Italian siblings

- Álvaro Pierri, classical guitarist

- Guido Santórsola, composer

- Daniel Viglietti, folk singer

- Roberto Musso Focaccio, rock singer(Cuarteto de nos)

- Ricardo Musso Focaccio, musician

- Santiago Tavella Nazzari, musician(Cuarteto de nos)

- Diego Martino, musician

- Frankie Lampariello, bass player

- Freddy Bessio, singer

- Eduardo Pedro Lombardo, musician

- Julio Cobelli, guitarist

- José María Carbajal Pruzzo, musician

- Alberto Mastrascusa Ilario, guitarist

- Ana Prada, musician

- Donatto Racciatti, musician

- Juan Campodónico, musician

- Fernando Santullo, musician

- Alberto Magnone, musician

- Estela Magnone, musician

- Olga Del Grossi, tango singer

- Rina Massardi, singer

- Rosita Melo, tango musician

- Pedro Dalton (Alejandro Fernández Borsani, Buenos muchachos), musician

- Juan Casanova, musician

- Gustavo Montemurro, musician

- Gabriel Peluffo, singer

- Gustavo Parodi, guitarist

- Guillermo Peluffo, singer

- Nicolás Bagattini, musician

- Ruben Melogno, singer

- Gonzalo Farrugia, drummer

- Bautista Mascia, singer and composer

- Luis Cesio, guitarist

Politics

- Rafael Addiego Bruno, jurist

- Danilo Astori, former vice president

- Alfredo Baldomir Ferrari, soldier

- Jorge Basso, Minister of Public Health of the Board Front party

- Azucena Berrutti, National Defense Minister from 2005 to 2008

- Graciela Bianchi, lawyer

- Eduardo Bonomi, politician

- Luis Brezzo, politician

- Diego Cánepa, lawyer and politician

- Roberto Canessa, medical student and one of the survivors of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571

- Lorenzo Carnelli, lawyer and politician

- Mario Cassinoni, medic, deputy, rector of the national university

- César Charlone Rodríguez, former vice president

- Juan Vicente Chiarino, lawyer and politician

- Alberto Demicheli, former president

- Emilio Frugoni, socialist politician

- Reinaldo Gargano, former foreign minister of Uruguay

- Luis Giannattasio Finocchietti, political figure

- Isabelino Canaveris, patriot of the National Party

- Telmo Languiller-Tornesi, Australian politician born in Uruguay

- Paulina Luisi, leader of the Uruguayan feminist movement

- Antonio Marchesano, lawyer and politician

- Aparicio Méndez Manfredini, political figure

- Rafael Michelini, politician

- Zelmar Michelini, father of Rafael Michelini, and reporter

- José Mujica Cordano, former president

- Benito Nardone, journalist

- Didier Opertti, lawyer

- Sergio Previtali, politician

- Laura Raffo, economist and politician

- Víctor Rossi, politician

- Julio María Sanguinetti, former president

- Jorge Sapelli, former vice president

- Raúl Sendic Antonaccio, Marxist lawyer and founder of the Tupamaros National Liberation Movement

- Líber Seregni, military officer and politician

- Héctor Martín Sturla, lawyer

- Enrique Tarigo, jurist

Religious figures

- Juan Francisco Aragone, cleric

- Antonio María Barbieri, cardinal

- Carlos María Collazzi, bishop of Mercedes

- Pablo Galimberti, cleric

- José Gottardi Cristelli, cleric

- Carlos Parteli, cleric

- Anna Maria Rubatto, nun

- Daniel Sturla, archbishop of Montevideo

- Milton Luis Tróccoli Cebedio, cleric

Science and Medicine

- Carlos Aragone, physicist

- Alice Armand Ugón, pediatrician

- Rodolfo Gambini, physicist and professor of the University of the Republic

- Juan Giambruno, cardiac surgeon

- Esmeralda Mallada Invernizzi, astronomer

- José Luis Massera, mathematician

- Enrique Loedel Palumbo, physicist

- Clemente Estable, biologist and researcher

Sports

- Nelson Abeijón Pessi, footballer

- Edgardo Adinolfi, footballer

- Peregrino Anselmo, footballer

- Claudio Arbiza Zanuttini, footballer

- Felipe Avenatti, footballer

- Daniel Baldi, footballer and writer

- Raúl Banfi, footballer

- Deivis Barone, footballer

- Daniel Bartolotta, footballer

- Fausto Batignani, footballer

- Víctor Manuel Battaini, footballer

- José Benincasa, footballer

- Víctor Hugo Berardi, basketball coach

- Felipe Berchesi, rugby player

- Mario Ludovico Bergara, footballer

- Francisco Bertocchi, footballer

- Adrián Bertolini, basketball player

- Nicolás Biglianti, footballer

- Joe Bizera, footballer

- Mariano Bogliacino, footballer

- Fiorella Bonicelli, tennis player

- Juan Boselli, footballer

- Juan Manuel Boselli, footballer

- Miguel Bossio, footballer

- Juan Bregaliano, boxer

- Nicolas Brignoni, rugby union player

- Marcelo Broli, footballer

- Francisco Bulanti, rugby union player

- Fabrizio Buschiazzo, footballer

- Wilmar Cabrera Sappa, footballer

- Washington Cacciavillani, footballer

- Mathías Calfani, basketball player

- Antonio Campolo, footballer

- Adhemar Canavesi, footballer

- Agustín Canobbio, footballer

- Carlos Canobbio, footballer

- Fabián Canobbio, footballer

- Osvaldo Canobbio, footballer

- Eitel Cantoni, racing driver

- Mariano Cappi, footballer

- Miguel Capuccini, footballer

- Alberto Cardaccio, footballer

- Mathías Cardaccio, footballer

- Fabián Carini, footballer

- Fernando Carreño Colombo, footballer

- Jorge Daniel Casanova, footballer

- Martín Cauteruccio, footballer

- Edinson Cavani, footballer

- Gastón Cellerino Grasso, footballer

- Pablo Cepellini, footballer

- Aníbal Ciocca, footballer

- Ignacio Conti, rugby union player

- Juan Carlos Corazzo, footballer

- Walter Corbo, footballer

- Erardo Cóccaro, footballer

- Sergio Cortelezzi, footballer

- Francisco Costanzo, boxer

- Claudio Dadómo Minervini, footballer

- José Luis Damiani, tennis player

- Luis de Agustini, footballer

- Giorgian De Arrascaeta Benedetti, footballer

- Fabián Estoyanoff Poggio, footballer

- Ricardo Faccio, footballer

- Mónica Falcioni, jumper

- César Falletti, footballer

- Maximiliano Faotto, footballer

- Damián Frascarelli, footballer

- Daniel Fascioli, footballer

- Francisco Fedullo, footballer

- Sebastián Fernández Miglierina, footballer

- Fabricio Ferrari, cyclist

- Juan Ferreri, footballer

- Mateo Fígoli, footballer

- Alfredo Foglino, footballer

- Marcelo Filippini, tennis player

- Sebastián Flores Stefanovich, footballer

- Daniel Fonseca, footballer

- Alejandro Foglia, sailor

- Diego Forlán Corazzo, footballer

- Bruno Fornaroli, footballer

- Jorge Fossati, footballer

- Enzo Francescoli, footballer

- Damián Frascarelli, footballer

- Víctor Frattini, footballer

- Francisco Frione, footballer

- Ricardo Alberto Frione, footballer

- Jorge Fucile, footballer

- Pablo Gaglianone, footballer

- Jhony Galli, footballer

- Schubert Gambetta, footballer

- Juan Manuel Gaminara, rugby union player

- Walter Gargano, footballer

- Leandro Gelpi, footballer

- Eduardo Gerolami, footballer

- Alcides Ghiggia, footballer

- Guillermo Giacomazzi, footballer

- Jorge Giordano, footballer

- Wilson Graniolatti, footballer

- Walter Guglielmone, footballer

- Gianni Guigou, footballer

- Nelson Gutiérrez Luongo, footballer

- Pablo Fernando Hernández Roetti, footballer

- Juan Legnazzi, footballer

- Alejandro Lembo, footballer

- Roberto Leopardi, footballer

- Mario Lorenzo, footballer

- Maximiliano Lombardi, footballer

- Adesio Lombardo, basketball player

- Diego Lugano, footballer

- Damián Macaluso, footballer

- Carlos Macchi, footballer

- Héctor Macchiavello, footballer

- Stefanía Maggiolini, footballer

- Ildo Maneiro Ghezzi, footballer

- Walter Mantegazza, footballer

- Williams Martínez Fracchia, footballer

- Ernesto Mascheroni, footballer

- Juan Cruz Mascia, footballer

- Roque Máspoli, footballer

- Roberto Matosas Postiglione, footballer

- Gonzalo Mastriani, footballer

- Andrés Mazali, footballer

- Nicolás Mazzarino, basketball player

- Leonardo Melazzi, footballer

- Ángel Melogno, footballer

- Bruno Méndez Cittadini, footballer

- Ana Lucía Migliarini de León, tennis player

- Leonardo Migliónico, footballer

- Facundo Milán, footballer

- Franco Milano, footballer

- Oscar Moglia, basketball player

- Paolo Montero, footballer

- José Nasazzi, footballer

- Ignacio Nicolini, footballer

- Martín Osimani, basketball player

- Jorge Ottati (Junior), sports announcer

- Jorge Ottati (Senior), sports announcer

- Antonio Pacheco D'Agosti, footballer

- Walter Pandiani, footballer

- Luciano Parodi, basketball player

- Joaquin Pastore, rugby union player

- Rodrigo Pastorini, footballer

- Alberico Passadore, rugby union player

- Ricardo Pavoni, footballer

- Luis Alberto Pedemonte, footballer

- Waldemar Pedrazzi, cyclist

- Pedro Pedrucci, footballer

- Walter Pelletti, footballer

- Diego Perrone, footballer

- Alfredo Petrone, boxer

- Pedro Petrone, footballer

- Paulo Pezzolano, footballer

- Miguel Ángel Piazza, footballer

- Luis Pierri, basketball players

- Víctor Pignanelli, footballer

- Rodolfo Pini, footballer

- Nitder Pizzani, footballer

- Gonzalo Pizzichillo, footballer

- Inti Podestá Mezzetta, footballer

- Diego Polenta Musetti, footballer

- Richard Porta Candelaresi, footballer

- Roberto Porta, footballer

- Gastón Puerari, footballer

- Ettore Puricelli, footballer

- Carlos Riolfo, footballer

- Federico Ricca, footballer

- Eduardo Risso, rower

- Pedro Rocha Franchetti, footballer

- Cristian Rodríguez Barotti, footballer

- Leandro Rodríguez Telechea, footballer

- Luis Romero, footballer

- Bernardo Roselli, chess master

- Diego Rossi, footballer

- Marcelo Rotti, footballer

- José Luis Russo, footballer

- Jonathan Sabbatini, footballer

- Antonio Sacco, footballer

- Mario Sagario, rugby union player

- Guillermo Sanguinetti, footballer

- Mateo Sanguinetti, rugby union player

- Raffaele Sansone, footballer

- Federico Sansonetti, tennis player

- Sergio Santín, footballer

- Cayetano Saporiti, footballer

- Marcelo Saracchi, footballer

- Carlos Scanavino, freestyle swimmer

- Héctor Scarone, footballer

- Juan Alberto Schiaffino, footballer

- Raúl Schiaffino, footballer

- Andrés Scotti, footballer

- Diego Scotti, footballer

- Robert Siboldi, footballer

- Marcelo Signorelli, basketball coach

- Gastón Silva Perdomo, footballer

- Martín Silva, footballer

- Gustavo de Simone, footballer

- Cristhian Stuani, footballer

- Alberto Suppici, football coach

- José Luis Tancredi, footballer

- Pablo Tiscornia, football coach

- Humberto Tomasina, footballer

- Lucas Torreira Di Pascua, footballer

- Marco Vanzini, footballer

- Ernesto Servolo Vidal, footballer

- Nicolás Vigneri, footballer

- Pedro Vigorito, footballer

- Tomaso Luis Volpi, footballer

- Javier Zeoli, footballer

- Jorge Zerbino, rugby union player

- Alfredo Zibechi, footballer

- Pedro Zingone, footballer

See also

References

- 1 2 "Numero iscritti suddivisi per ripartizioni estere" (in Italian). Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Los árboles sin raíces, mueren" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ Arocena & Aguiar 2007, p. 22

- ↑ Bengochea, Julieta (June 2014). "Inmigración reciente en Uruguay: 2005 - 2011" (PDF). Serie tesis de maestría en demografía y estudios de población (in Spanish). Facultad de Ciencias Sociales: 57-58. ISSN 2393-6479. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Arocena & Aguiar 2007, p. 40

- 1 2 3 Pi Hugarte, Renzo (9 October 2001). "Elementos de la cultura italiana en la cultura del Uruguay" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ↑ Tron, Ernesto; Ganz, Emilio H (1958). Historia de las colonias valdenses sudamericanas en su primer centenario, 1858-1958 (in Spanish). Librería Pastor Miguel Morel.

- ↑ "Un tour por el puerto de Gaboto" (in Spanish). El País. 12 June 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "Localizan en ríos San Salvador y Uruguay primer asentamiento europeo fundado por Sebastián Gaboto" (in Spanish). LARED21. 12 June 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ "Gaboto se instaló en costa de Soriano hace 500 años" (in Spanish). El País. 12 May 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ Garrappa Albani, Jorge. "Sulle tracce dei marinai italiani nel Río de la Plata" (in Italian). Lombardi nel Mondo. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ↑ Maggi, Carlos (24 August 2008). "La Paloma, la historia y el futuro" (in Spanish). El País. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ Otheguy, Martín (9 February 2018). "De cómo una casa de la Ciudad Vieja ayudó a Einstein a convalidar la teoría de la relatividad" (in Spanish). Montevideo Portal. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ↑ Blixen, Hyalmar (12 June 1989). "En el segundo centenario de la expedición Malaspina (1789 –1989)" (in Spanish). Diario Lea. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Contu, Martino (January–March 2015). "Las relaciones entre el Reino de Italia y Uruguay de 1861 al fascismo" (PDF). Revista Inclusiones (in Spanish). 2 (1): 204-228. ISSN 0719-4706. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2018.

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, p. 10

- 1 2 3 Arocena & Aguiar 2007, p. 38

- 1 2 3 Adamo 1999, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Devoto 1993, pp. 4 and 100

- 1 2 Oddone, Juan A. "Fuentes uruguayas para la historia de la inmigración italiana" (in Spanish). Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- 1 2 Adamo 1999, p. 17

- 1 2 Contu, Martino (January–December 2011). "Le relazioni italo-uruguaiane, l'emigrazione italiana e la rete consolare della Banda Orientale nel Regno Sardo e nell'Italia unita con particolare riferimento ai vice consoli uruguaiani in Sardegna" (PDF). Ammentu (in Italian) (1): 103-117. ISSN 2240-7596. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2018.

- ↑ "Rinden tributo a Garibaldi en Salto" (in Spanish). LARED21. 4 July 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "José Garibaldi". 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 6

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 20

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 1

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 36

- ↑ Oddone 1965, p. 40

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 34

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 67

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 174

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 68

- 1 2 Adamo 1999, p. 69

- ↑ Adamo 1999, pp. 84–85

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 118

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 110

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 111

- ↑ "Italian Jews in Uruguay". Brecha. 11 March 2014. (in Spanish)

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 109

- 1 2 "Uruguay, lingua italiana alle elementari: ma un'ora e mezza a settimana non basta" (in Italian). Italia chiama Italia. 5 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Adamo 1999, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Adamo 1999, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 125

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 120-121

- ↑ Bresciano 2010, p. 113

- ↑ "Scholar and Patriot". Manchester University Press – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Giuseppe Garibaldi (Italian revolutionary)". Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 1 2 "Inmigrantes: 60% de la población de Carmelo son descendientes de italianos, y un 35% de vascos" (in Spanish). El Eco Digital. 8 August 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- 1 2 Devoto 1993, pp. 165–166

- ↑ Barrios 2008, pp. 237–239

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 142

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 168

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 10

- 1 2 Devoto 1993, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Zito, José María. "Crónica del barrio Palermo". Al día. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 244

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 243

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 167

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 78

- 1 2 Devoto 1993, p. 242

- ↑ "Piriápolis" (in Spanish). Maldonado Turismo. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ "Piriápolis, meta esclusiva dell'Uruguay ispirata alla riviera ligure" (in Italian). Italiaonline S.p.A. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- ↑ "Se consumó el hermanamiento: Alcaldes de Diano Marina (Italia) y Piriápolis (Uruguay) firmaron acuerdo". La Prensa. 4 January 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- 1 2 Devoto 1993, p. 101

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 66

- ↑ Devoto 1993, pp. 18–19

- 1 2 Adamo 1999, p. 82

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 20

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 105

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 12

- ↑ Devoto 1993, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 32

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 33

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 57

- ↑ Adamo 1999, pp. 82–83

- ↑ Adamo 1999, p. 80

- ↑ Adamo 1999, pp. 81–82

- ↑ "Isla de Flores, la olvidada Babel donde desembarcaron los miles de inmigrantes que construyeron Uruguay" (in Spanish). El Observador. 14 June 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- 1 2 Bresciano 2010, pp. 126–127

- 1 2 Bresciano 2010, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Barrios 2008, pp. 146–147

- ↑ Crolla 2013, p. 50

- 1 2 Lo Cascio, Vincenzo. "Imaginario e integración de los italianos en Latinoamérica" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de Ámsterdam. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ "La influencia del pensamiento garibaldino en la conformación republicana uruguaya". GOFMU. 28 April 2007. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Barrios 2008, pp. 144–145

- ↑ Barrios 1994, pp. 108–111

- ↑ Bresciano 2010, p. 129

- ↑ Barrios 2008, p. 31

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 149-151

- ↑ Klee 2009, p. 11

- ↑ Barrios 2008, p. 32

- ↑ Barrios 2008, pp. 154–156

- 1 2 Conde, Oscar (2011). "2 - El cocoliche, el farruco y el valesco". Lunfardo (in Spanish). Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial Argentina. ISBN 9789870420248.

- 1 2 Klee 2009, p. 188

- ↑ Balderston, Daniel; González, Mike; López, Ana M. (2002). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Latin American and Caribbean Cultures. Routledge. p. 881. ISBN 9781134788521.

- ↑ Klee 2009, p. 189

- ↑ Meglioli, Gladys Aballay (2005). El español peninsular y americano de la región andina en los atlas lingüísticos (in Spanish). Effha. p. 101. ISBN 9789506054007.

- ↑ "El porteñísimo lunfardo se renueva con palabras del rock y de la cumbia" (in Spanish). 21 August 2011. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ Meo-Zilio, Giovanni. "Italianismos generales en el español rioplatense" (PDF) (in Spanish). Universitá degli Studi di Firenze. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ↑ Conde, Oscar (2016). La pervivencia de los italianismos en el español rioplatense (PDF). Vol. 57. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Devoto 1993, pp. 321–322

- 1 2 3 Devoto 1993, p. 320

- 1 2 Devoto 1993, p. 323

- ↑ Bresciano 2010, p. 131

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 358

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 324

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 326

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 360

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 369

- 1 2 3 Ruocco, Ángel (15 June 2012). "¿Cocina italiana, dijo?" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ "De cocción fácil y rápida" (in Spanish). El País. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (1 June 2012). "La verdad de la milanesa" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ↑ "La verdad de la milanesa: dónde nació y por qué es tan popular" (in Spanish). El País. 5 June 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ↑ Vidart, Daniel; Pi Hugarte, Renzo (1969). "El legado de los inmigrantes II". Nuestra Tierra (39): 34.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (27 September 2016). "Reivindicados los tallarines y los tricampeones mundiales" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (8 June 2012). "De cómo los fideos se hicieron imprescindibles" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "La historia de la tradición de los ñoquis para cada 29" (in Spanish). El País. 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ Martínez, Ignacio (29 February 2000). "Los ñoquis y el 29" (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "¿Por qué los argentinos comen ñoquis el 29 de cada mes y qué tiene que ver eso con los empleados públicos?" (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ "Ñoquis el 29" (in Spanish). 3 May 2012. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ "El ñoquis de cada 29" (in Spanish). 29 November 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- 1 2 Petryk, Norberto. "Los ñoquis del 29" (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ↑ "Ñoquis del 29: origen de una tradición milenaria" (in Spanish). 29 July 2004. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (4 August 2014). "Los Capeletis a la Caruso cumplieron 60 años" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Con la tradición de la pasta italiana en Salto". Diario El Pueblo. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "El negocio de las pastas frescas". El País. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "La Spezia apuesta a los restaurantes de pasta rápida" (in Italian). El Observador. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Fábrica de pastas La Spezia cerró tras 79 años; 120 personas sin empleo". 27 March 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- ↑ "Chiude "La Spezia", impero uruguaiano della pasta fondato dagli emigranti" (in Italian). Città della Spezia. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 Ruocco, Ángel (10 August 2012). "Pizza y fainá: vinieron de Italia y se hicieron uruguayas" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (17 August 2012). "De masa alta o baja, circular o rectangular, siempre pizza" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (6 September 2013). "¡QUÉ NO NOS FALTE TASENDE!" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "Día del Auténtico Fainá" (in Spanish). Montevideo Portal. 27 August 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ "El fainá en Uruguay cumple 92 años". Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Nicola, Silvana (18 May 2018). "Tres días a puro Chivito weekend" (in Italian). El País. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "URUGUAY RINDE HOMENAJE A SU PLATO MÁS TÍPICO EN EL "CHIVITO WEEKEND"" (in Spanish). Monte Carlo TV. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Mellizo, Álvaro (6 February 2014). "El 'chivito', 70 años como suculento símbolo de la cocina uruguaya" (in Spanish). El Mundo. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Trujillo, Valentín (14 January 2014). "El homenaje al inventor del chivito" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Sequeira, Alejandro (2014). "2". El Rey de los sándwiches de carne: chivito (in Spanish). Ediciones de la Plaza. ISBN 978-9974482449.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (14 September 2012). "Un regalo de los genoveses al Uruguay: el chupín" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (15 August 2013). "Buseca: un plato criollo con nombre tano" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (6 May 2013). "Tortas fritas: ¿nacionales o importadas?" (in Spanish). El Observador. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ↑ "Un antropólogo de la culinaria uruguaya" (in Spanish). El Observador. 4 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Torta pascualina, la receta que encantó a Paul McCartney" (in Spanish). 14 September 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ "Pasta Frola" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Acuña, Cecilia (21 May 2018). "La historia de la pasta frola: de la masa italiana al relleno español" (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ "Pan dulce: una tradición, diferentes versiones" (in Spanish). El Observador. 21 December 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Massini". Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ↑ Ruocco, Ángel (25 February 2016). "Una milenaria historia que nos deja helados". El Observador. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- 1 2 "Helados uruguayos con sabor a tradición" (in Spanish). El Observador. 22 January 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Dobal, Marcela (5 January 2018). ""Nuestra fábrica no daba abasto"" (in Spanish). El País. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "VINO URUGUAYO Se declara bebida nacional" (PDF) (in Spanish). Parlamento. 15 August 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "4ta Etapa" (in Spanish). I.NA.VI. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Beretta Curi 2015, p. 28

- ↑ Beretta Curi, Alcides (2009). "Inmigración, vitivinicultura e innovación: el emprendimiento de Buonaventura Caviglia en la localidad de Mercedes (1870-1916)". Mundo Agrario (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Estudios Histórico Rurales. 9 (18). ISSN 1515-5994.

- ↑ Beretta Curi 2015, pp. 95–96

- ↑ Rodríguez Mezzetta, Pablo (24 July 2018). "Tradizione Italiana" (in Spanish). Bodegas del Uruguay. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ "Grappa italiana" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- ↑ Benedetti, Ramiro (2 July 2016). "Grappa, una tradición italiana dignamente representada en Uruguay" (in Spanish). Bodegas del Uruguay. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 Gavinelli, Corrado (30 November 2016). "Il quartiere Peñarol di Montevideo" (in Italian). Vita Diocesana Pinerolese. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ↑ Lamela, Luis (9 February 2017). "Una dumbriesa ligada a los orígenes del Peñarol" (in Spanish). La Voz de Galicia. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ "Hace 110 años los ingleses se instalaban en Peñarol" (in Spanish). 2 May 2001. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Canel, Eduardo (2010). Barrio Democracy in Latin America: Participatory Decentralization and Community Activism in Montevideo. Penn State Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780271037325.

- ↑ "Spencer secures Penarol's place in the pantheon". 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2018.

- ↑ Montemuiño, Agustín (24 September 2014). "11 equipos representativos de comunidades que compitieron en AUF" (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ↑ Cervi, Gino (9 June 2014). "Azzurro oriundo, ma serve in un Mondiale?" (in Italian). GQ. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ↑ Enciclopedia dello Sport, volume Calcio (in Italian). Istituto della "Enciclopedia Italiana". 2004. p. 603.

- ↑ "FIFA World Cup Awards: All-Star Team". Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ↑ "Los uruguayos con doble nacionalidad" (in Spanish). 25 December 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Devoto 1993, p. 385

- 1 2 3 Brenna, Paulo G. (1918). L'emigrazione italiana nel periodo ante bellico (in Italian). R. Bemporad & Figlio. p. 181.

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 386

- ↑ "Banco Italiano del Uruguay" (in Spanish). Banco Central del Uruguay. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Bresciano, Juan Andrés (2017). "La Scuola Italiana di Montevideo davanti agli impeti del fascismo. Dalla resistenza alla resa (1922-1942)". Giornale di Storia Contemporanea (in Italian). XXI (2): 3. ISSN 2037-7975.

- ↑ Devoto 1993, p. 387

- ↑ "Italianos celebraron en Paysandú 71º aniversario de la República de Italia" (in Spanish). Diario El Telégrafo. 3 June 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ↑ Connio, Francisco (5 August 2013). "Correo emitió sello por 50 años de Asociación Calabresa" (in Spanish). La República. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "Circolo Lucano del Uruguay" (in Spanish). Circolo Lucano del Uruguay. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ "Il fallimento della Dante Alighieri continua ad essere un grande mistero a Montevideo" (in Italian). La Gente d'Italia. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ↑ Casini, Stefano (24 March 2018). "Con Renato Poma la cultura italiana in Uruguay riprende il volo" (in Italian). La Gente d'Italia. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, pp. 151–152

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 18

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 21

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, p. 44

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 52

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 55

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 65

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 70

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 95

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 97

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 143

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 166

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 175

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, p. 178

- ↑ "L'Eco d'Italia". Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ↑ "Scuola Italiana di Montevideo". Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ↑ "Spazio Italia". Archived from the original on 20 January 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ "La gente d'Italia". Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, pp. 179–180

- 1 2 Sergi 2014, p. 181

- ↑ Sergi 2014, pp. 197–198

- ↑ Sergi 2014, p. 199

Sources

- Arocena, Felipe; Aguiar, Sebastián (2007). Multiculturalismo en Uruguay: ensayo y entrevistas a once comunidades culturales (in Spanish). Ediciones Trilce. ISBN 9789974324558.

- Adamo, Gianfranco (1999). Facetas históricas de la emigración italiana al Uruguay (in Spanish). [ISBN unspecified]

- Barrios, Graciela; Mazzolini, Susana; Orlando, Virginia (1994). "Lengua, cultura e identidad: los italianos en el Uruguay actual". Presencia italiana en la cultura uruguaya (in Spanish). Universidad de la República, centro de Estudios Italianos. [ISBN unspecified]

- Barrios, Graciela (2008). Etnicidad y lenguaje. La aculturación sociolingüística de los inmigrantes italianos en Montevideo (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de la República. ISBN 978-9974-0-0472-6.

- Beretta Curi, Alcides (2015). Historia de la viña y el vino de Uruguay. El viñedo y su gente (1870–1930) (in Spanish). Universidad de la República. ISBN 978-9974-0-1306-3.

- Bresciano, Juan Andrés (2010). Un paese che cambia: saggi antropologici sull'Uruguay tra memoria e attualità (in Italian). Centro de Informazione e Stampa Universitaria. ISBN 978-8879754811.

- Crolla, Adriana Cristina (2013). Las migraciones ítalo—rioplatenses. Memoria cultural, literatura y territorialidades (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad Nacional del Litoral. ISBN 978-987-657-899-8.

- Devoto, Fernando (1993). L'emigrazione italiana e la formazione dell'Uruguay moderno (in Italian). Edizioni della Fondazione Giovanni Agnelli. ISBN 8878600695.

- Klee, Carol A. (2009). El español en contacto con otras lenguas (in Spanish). Georgetown University Press. ISBN 9781589016088.