| Weser–Rhine Germanic | |

|---|---|

| Rhine–Weser Germanic, Istvaeonic, Istveonic, Franconian[1] | |

| Geographic distribution | Around the Weser and Rhine rivers |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | macr1270 |

The distribution of the primary Germanic languages in Europe c. AD 1:

Weser–Rhine Germanic, or Istvaeonic

| |

Weser–Rhine Germanic is a proposed group of prehistoric West Germanic dialects which would have been both a direct ancestor of Dutch and a notable substratum influencing West Central German dialects.[2] The term was introduced by the German linguist Friedrich Maurer as a replacement for the older term Istvaeonic, with which it is essentially synonymous. The term Rhine–Weser Germanic is sometimes preferred.[3]

Nomenclature

The term Istvaeonic is derived from the Istvæones (or Istvaeones), a culturo-linguistic grouping of Germanic tribes, mentioned by Tacitus in his Germania.[4] Pliny the Elder further specified its meaning by claiming that the Istævones lived near the Rhine.[5] Maurer used Pliny to refer to the dialects spoken by the Franks and Chatti around the northwestern banks of the Rhine, which were presumed to be descendants of the earlier Istvaeones.[6] The Weser is a river in Germany, east of and parallel to the Rhine. The terms Rhine–Weser or Weser–Rhine, therefore, both describe the area between the two rivers as a meaningful cultural-linguistic region.

Theory

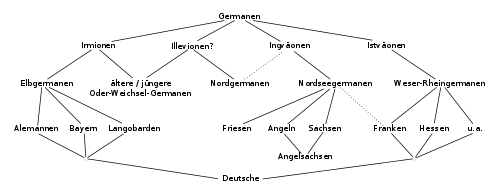

Maurer asserted that the cladistic tree model, ubiquitously used in 19th and early 20th century linguistics, was too inaccurate to describe the relation between the modern Germanic languages, especially those belonging to its Western branch. Rather than depicting Old English, Old Dutch, Old Saxon, Old Frisian and Old High German to have simply 'branched off' a single common 'Proto-West Germanic', he proposed that there had been much more distance between the languages and the dialects of the Germanic regions.[7]

Weser–Rhine Germanic seems to have been transitional between Elbe Germanic and North Sea Germanic, with a few innovations of their own.[8]

References

- ↑ Stefan Müller, Germanic syntax: A constraint-based view, series: Textbooks in Language Sciences 12, Language Science Press, Berlin, 2023, p. 3

- ↑ Maurer 1952, pp. 123–126, 175–178.

- ↑ Henriksen & van der Auwera 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Tac. Ger. 2

- ↑ Plin. Nat. 4.28

- ↑ Maurer 1952.

- ↑ Johannes Hoops, Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer: Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde: Band 7; Walter de Gruyter, 1989, ISBN 9783110114454 (pp 113–114).

- ↑ Orrin W. Robinson (2003). Old English and its Closest Relatives: A Survey of the Earliest Germanic Languages. Routledge. pp. 225–226. ISBN 1134849001.

Bibliography

- Tacitus, Germania (1st Century AD). (in Latin)

- Gregory of Tours (1997) [1916]. Halsall, Paul (ed.). History of the Franks: Books I–X (Extended Selections). Translated by Ernst Brehaut. Columbia University Press; Fordham University.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Henriksen, Carol; van der Auwera, Johan (2013) [First published 1994]. "1. The Germanic Languages". In van der Auwera, Johan; König, Ekkehard (eds.). The Germanic Languages. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-415-05768-4.

- Maurer, Friedrich (1952) [First edition 1942]. Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanische und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes- und Volkskunde. Bibliotheca Germanica, 3 (3rd, revised, extended ed.). Bern, Munich: Francke.

- James, Edward (1988). The Franks. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17936-4.