Madrassa in Bukhara | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 66 million[1][2] (90.6%) | |

| Religions | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Languages | |

Liturgical

CommonSome Turkic languages, Tajik (Persian) and Arabic (Sacred) |

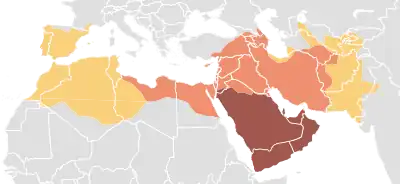

Islam in Central Asia has existed since the beginning of Islamic history. Sunni branch of Islam is the most widely practiced religion in Central Asia. Shiism of Imami and Ismaili denominations predominating in the Pamir plateau and the western Tian Shan mountains (almost exclusively Ismailis), while boasting to a large minority population in the Zarafshan river valley, from Samarkand to Bukhara (almost exclusively Imamis).[10] Islam came to Central Asia in the early part of the 8th century as part of the Muslim conquest of the region. Many well-known Islamic scientists and philosophers came from Central Asia, and several major Muslim empires, including the Timurid Empire and the Mughal Empire, originated in Central Asia. In the 20th century, severe restrictions on religious practice were enacted by the Soviet Union in Soviet Central Asia and the People's Republic of China in Xinjiang.

History

Arrival of Islam and Medieval period

The Battle of Talas in 751 between the Abbasid Caliphate and the Chinese Tang dynasty for control of Central Asia was the turning point, initiating mass conversion into Islam in the region.

Most of the Turkic khanates converted to Islam in the 10th century. The arrival in Volga Bulgaria of Ahmad ibn Fadlan, ambassador of the caliph of Baghdad, on May 12, 922 is celebrated as a holiday in modern-day Tatarstan.

Urban centers were the first to adopt Islam in the region due to many socio-political and economic institutions coming under the influence of Muslim leadership. Rural regions were Islamized significantly later. While urban areas generally tended to be spiritually influenced by the ulema, Sufi mystics held prominent authority in the rural regions.[11]

Islamisation of the region has had a profound impact on the native cultures in the region molding them as a part of Islamic civilization. Islamisation in the region has also had the effect of blending Islam into native cultures, creating new forms of Islamic practices, known as folk Islam, the most prominent proponent of which was Khoja Akhmet Yassawi whose Sufi Yeseviye sect appealed greatly to local nomads. Some have proclaimed that Yassawi was a Khwajagan, however, some scholars insist that his influence on the Shi'a Alevi and Bektashi cannot be underestimated.

Until the Mongol invasion of Central Asia in the 13th century, Samarkand, Bukhara, and Urgench flourished as centers of Islamic learning, culture and art in the region. Mongol invasion halted the process for a half-century. Other areas such as Turkistan became more strongly influenced by Shamanist elements which can still be found today.

Central Asian Islamic scientists and philosophers, including Al-Khwarzimi, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Farabi, and Avicenna made an important impact on the development of European science in the ensuing centuries.

Turko-Mongolian tribes almost as whole were slow to accept certain Islamic tenets, such as giving up the consumption of alcohol or bathing before prayer. This is, however, believed to relate more directly to their nomadic lifestyle and local tradition than their faith in God and devotion to Islamic law and text.

Russian Empire

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

After conquests in the region by the Russian Empire in the 1860s and 1870s, western Central Asia came under Russian control and was incorporated into the empire as a Governor-Generalship led by Konstantin von Kaufman. Russian authorities debated what position they should take on Islam in the newly conquered territories. Some advocated a policy of religious repression, citing the ongoing Dungan Revolt in the neighboring Qing Empire as proof of the potential "threat" of Islam. Others, such as General Kaufman and his superior Dmitry Milyutin, preferred a policy of mild religious tolerance. Kaufman was nevertheless concerned about pan-Islam movements that would cause the Muslims of Russian Turkistan to view anyone other than the czar as their ruler.[12]

Soviet Union

While the practice of Islam was broadly tolerated by the Russian Empire during its rule over Central Asia from the mid-1860s to 1917, the advent of Soviet rule following the Russian Revolutions of 1917 and the subsequent civil war brought with it Marxist opposition to religion. During the first few years of Bolshevik rule in the early 1920s, Soviet officials took a pragmatic approach by prioritizing other goals (attempting to modernize culture, building schools, improving the position of women) in order to solidify their hold on Central Asia. During this time, the Bolsheviks cooperated with the Jadids (Muslims working towards social and cultural reforms such as improved education) to accomplish their goals. In the process, the Bolsheviks created a new political elite favorable towards Marxist ideology by using propaganda and appointing officials favorable towards their policies during the division of Central Asia into separate republics along ethnic lines in the 1920s and 1930s.[13]

In 1926, the Soviet government decided it had consolidated control over Central Asia sufficiently to shift official policy from toleration of Islam to condemnation. The government closed private religious schools in favor of state-run public ones. Between 1927 and 1929, the state ran a campaign to shut down mosques in Central Asia. This operation was not well documented, but existing accounts indicate that it was often violent and poorly controlled, often carried out by self-appointed officials who arrested imams and destroyed buildings, denouncing Islam as an enemy of communism.[14]

Despite these assaults, Islam in Central Asia survived Soviet rule in the following decades. However, it was transformed in the process: instead of part of the public sphere, Islam became family-oriented, "localized and rendered synonymous with custom and tradition."[15] This led to a homogenization of practice; as religious authorities could not publish treatises or often even communicate with one another, the store of religious knowledge available vastly decreased. Additionally, Islam was largely removed from the public discourse, especially in terms of its influence on morals and ethical values.[16] What religious practice that was permitted by the Soviet government was regulated by the Spiritual Administration of the Muslims of Central Asia and Kazakhstan.

1980s, 1990s, and Islamic Revival

The policy of glasnost put into practice by Mikhail Gorbachev in the mid-1980s meant that by 1988 the Soviet government relaxed its controls on Islam. As a result, there was a rapid religious revival, including new mosques, literature, and the return of private religious schooling. Many Central Asians were interested in the ethical and spiritual values that Islam could offer.[17][18]

The revival accelerated further following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. For many, Islam constituted a national heritage that had been repressed during the Soviet era. Additionally, relaxed travel restrictions under Gorbachev enabled cultural exchange with other Muslim countries; Saudi Arabia, for example, sent copies of the Qur'an into the Soviet Union in the late 1980s. Islam, as practiced in Central Asia, became much more varied in this short time.[19] Furthermore, Islam was attractive because it offered alternatives and solutions to the myriad political and economic problems facing the republics in the wake of the Soviet Union's collapse.[20]

However, the governments of the Central Asian republics were wary of Islam in the political sphere. Their fears of undue influence were soon justified by the outbreak of the Tajik Civil War in 1992, between the Tajik government and a coalition of opponents led by a radical Islamist group called the Islamic Renaissance Party.[21] The civil war, which lasted until 1997, demonstrated to the other former Soviet republics the dangers posed by Islamic opposition groups. The takeover in 1996 of Afghanistan by the Taliban further emphasized that threat.[22]

The Islamic Renaissance Party (IRP) was one of several similar Islamic opposition groups, including the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), which also fought against the Tajik government in the civil war.[23] The IRP had its origins in underground Islamic groups in the Soviet Union. It was formed in 1990 in Astrakhan by a group consisting mostly of Tatar intellectuals, with separate branches for each Soviet republic. It was in fact registered as an official political party in Russia, but was banned by the Central Asian communist governments.[24] Partly as a result of this oppression, political opposition erupted into the violence of the civil war in Tajikistan, in which over 50,000 people were killed out of a population of 6 million and another 250,000 fled the country to Afghanistan, Uzbekistan or elsewhere.[25] Following the civil war, the Tajik government incorporated Islamic groups into the government in order to prevent future tensions. However, the other Central Asian republics did not follow this example, continuing instead to repress and persecute Islamic groups rather than allow them to participate in the political process.[26]

Not all Islamic movements were violent like the IRP; the most popular radical Islamic movement in Central Asia during the 1990s was the non-violent Hizb ut-Tahrir. Though it does not espouse the same violent methods as groups such as the IRP and IMU, its stated goal is to unite all Muslim countries through peaceful methods and replace them with a restored caliphate. For this reason, governments in Central Asia consider it a threat and have outlawed it as a subversive group in the Central Asian republics.

21st century

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, foreign powers took a much greater interest in preventing the spread of radical Islamic terrorist organizations such as the IMU. The Central Asian republics offered their territory and airspace for use by the US and its allies in operations against the Taliban in Afghanistan, and the international community recognized the importance of ensuring stability in Central Asia in order to combat terrorism.[27]

Powers such as the United States, Russia, and China were not only interested in fighting terrorism; they used the war on terror in order to advance their political and economic agendas in the region, particularly over the exploitation of Central Asian energy resources.[27]

In Tajikistan, the government took advantage of this shift in international attitude in order to erode the position of Islam in politics, taking steps such as forbidding the hijab (which is not traditional in Tajikistan, due to Soviet rule) in public schools and reducing the legal rights of Islamic groups.[22]

Since 2001, ethnic and religious tensions in the Central Asian republics combined with endemic poverty and poor economic performance have made them increasingly volatile. However, governments as often use Islamic groups as a justification for repression and crackdowns as those groups are the cause of violence, if not more often. For example, in May 2005 the Uzbek government massacred over 700 of its own civilians demonstrating following a trial of 23 suspected Islamic radicals, saying that they were terrorists. Though the events of the massacre were complex, this simplistic account appears to be false; instead, it was a case of the Uzbek government repressing peaceful protesters, perhaps attempting to prevent the sort of popular revolt that had occurred two months earlier in Kyrgyzstan, toppling President Askar Akayev.[28] Overall, Islamic militancy in Central Asia is not a major threat to regional stability compared to the myriad social and economic problems—such environmental devastation around the Aral Sea, endemic poverty, poor education—that plague the region.[29] Central Asian expert Adeeb Khalid, writes that the situation in Central Asia demonstrates most of all that Islam is a complex phenomenon that rejects easy categorization into "good" and "bad," "moderate" and "extremist," and that the form Islam takes in Central Asia is not the same as the form it takes elsewhere. "For observers," he writes, "it is critical to have perspective, to discern clearly the political stakes at issue...and to separate the disinformation dished out by the regimes from the actual conduct of Muslims."[30]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Rowland, Richard H. "CENTRAL ASIA ii. Demography". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 2. pp. 161–164. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- ↑ "The Global Religious Landscape" (PDF). Pew. December 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Al-Jallad, Ahmad (30 May 2011). "Polygenesis in the Arabic Dialects". Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. BRILL. doi:10.1163/1570-6699_eall_EALL_SIM_000030. ISBN 9789004177024.

- ↑ "The results of the national population census in 2009". Agency of Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 12 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2010.

- ↑ "Tajikistan". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ↑ "Kyrgyzstan". Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project. 2010. Retrieved 2018-08-01.

- ↑ Trilling, David (2015-05-08). "Tajikistan debates ban on Arabic names as part of crackdown on Islam". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2017-05-25.

- ↑ Trilling, David. "Islam in Uzbekistan". CIA. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- ↑ "Religion in Turkmenistan". Facts and Details. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ↑ Naumkin, 38.

- ↑ Foltz, Richard C. (2006-10-26). "Islamic Communities in Central Asia". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195137989.003.0045.

- ↑ Brower, 116.

- ↑ Khalid, 65-71.

- ↑ Khalid, 71-73.

- ↑ Khalid, 82.

- ↑ Khalid, 83.

- ↑ Schwab, Wendell (Summer 2011). "Establishing an Islamic niche in Kazakhstan: Musylman Publishing House and its publications." Central Asian Survey, 30 (2): 227-242.

- ↑ Khalid, 120-121.

- ↑ Khalid, 121-123.

- ↑ Karagiannis, 20

- ↑ Rashid, Jihad, 102.

- 1 2 Khalid, 123.

- ↑ Karagiannis, 3

- ↑ Rashid, Jihad 98.

- ↑ Rashid, Fires, 50-52.

- ↑ Rashid, Fires, 53-55.

- 1 2 Van Wie Davies, 1-5.

- ↑ Khalid, 199.

- ↑ Khalid, 202.

- ↑ Khalid, 203.

Sources

- Biard, Aurelie. Bibliography: Religion in Central Asia (Tsarist Period to 2016). CAP Papers 169. http://centralasiaprogram.org/blog/2016/07/01/bibliography-religion-in-central-asia-tsarist-period-to-2016/

- Brower, Daniel R, “Islam and Ethnicity: Russian Colonial Policy in Turkestan,” in Russia's Orient: Imperial Borderlands and Peoples, 1700-1917, ed. Daniel R. Brower and Edward J. Lazzerini. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997).

- Crews, Robert D. (2006). For Prophet and Tsar: Islam and Empire in Russia and Central Asia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02164-9.

- Karagiannis, Emmanuel (2010). Political Islam in Central Asia: The Challenge of Hizb ut-Tahrir. New York, New York: Routledge.

- Khalid, Adeeb (2007). Islam After Communism: Religion and Politics in Central Asia. Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24927-1.

- Naumkin, Vitaly V. (2005). Radical Islam in Central Asia: Between Pen and Rifle. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-7425-2930-4.

- Paksoy, HB (1989). ALPAMYSH: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule. Hartford, Connecticut: AACAR. ISBN 978-0962137907. Archived from the original on 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- Paksoy, HB (1999). Essays on Central Asia. Lawrence, KS: Carrie.

- Rashid, Ahmed (Spring 2001). "The Fires of Faith in Central Asia". World Policy Journal. 18 (1): 50–52. doi:10.1215/07402775-2001-2001.

- Rashid, Ahmed (2007). Jihad: The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.

- Schwab, Wendell (June 2011). "Establishing an Islamic niche in Kazakhstan: Musylman Publishing House and its publications". Central Asian Survey. 30 (2): 227–242. doi:10.1080/02634937.2011.565229. S2CID 144393697.

- Van Wie Davies, Elizabeth; Azizian, Rouben (2007). Islam, Oil and Geopolitics: Central Asia After September 11. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–5.