Irving Kane Pond | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Irving Pond portrait published in Architectural Record, 1912 | |

| Born | May 1, 1857 Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | September 29, 1939 (aged 82) Washington, D. C., U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Michigan |

| Occupation(s) | Architect and author |

| Years active | 1879-1939 |

Irving Kane Pond (May 1, 1857 – September 29, 1939) was an American architect, college athlete, and author. Born in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Pond attended the University of Michigan and received a degree in civil engineering in 1879. He was a member of the first University of Michigan football team and scored the first touchdown in the school's history in May 1879.

After graduating from Michigan, Pond moved to Chicago where he worked as an architect from 1879 to 1939. He began his architectural career as a draftsman in the offices of William LeBaron Jenney and worked as the head draftsman in the office of Solon Spencer Beman during the construction of the planned Pullman community. In 1886, Pond formed the Chicago architectural firm Pond and Pond in partnership with his brother Allen Bartlitt Pond. The Pond brothers worked together for more than 40 years, and their buildings are considered to be among the best examples of Arts and Crafts architecture in Chicago. The Ponds gained acclaim as the architects of Jane Addams' Hull House, and three of their buildings have been declared National Historic Landmarks—the Hull House dining hall, the Lorado Taft Midway Studios, and the Frank R. Lillie House. Pond became a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1900 and served as president of the American Institute of Architects from 1910 to 1911.

Pond was also a leader in the Chicago arts community in the late 19th and early 20th century. He was one of the founders of the Eagle's Nest Art Colony and a member of the Chicago Literary Club from 1888 to 1939. Pond was also a published author of fiction, poetry, and essays on art and architecture. He was also a frequent contributor to architectural journals and wrote for The Dial and Gustav Stickley's The Craftsman. In 1918, he published the book The Meaning of Architecture summarizing his views on the role of architecture in the broader spectrum of the arts.

Early years and education

Pond was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1857.[1] He was the son of Elihu Pond and Mary Barlow (Allen) Pond. His father was a member of the Michigan State Senate, warden of the Michigan State Prison for two years, the first president of the Michigan Press Association and the editor and publisher of the weekly newspaper, the Argus of Ann Arbor.[1][2] Growing up in Ann Arbor, Pond lived in a house on the current site of the Michigan Union, a building he later designed. His next door neighbor as a child was the noted legal scholar, Thomas M. Cooley. Cooley encouraged the young Pond, who aspired to be an artist, by presenting him with his first art book and by commissioning Pond to draw a set of cartoons of the Cooley family.[3] Pond attended the public schools in Ann Arbor before enrolling at the University of Michigan.[1][4]

Pond was an engineering student at the University of Michigan from 1875 to 1879 and took architecture classes taught by Chicago architect William LeBaron Jenney. Six years later, Jenney gained fame for designing Chicago's metal-framed Home Insurance Building. In 1934, Pond wrote an article challenging the popular assertion that the Home Insurance Building was the first steel-framed skyscraper.[5]

While attending the University of Michigan, Pond was a member of the first Michigan Wolverines football team. On May 30, 1879, the team played its first intercollegiate football game against Racine College at White Stocking Park in Chicago. The Chicago Tribune called it "the first rugby-football game to be played west of the Alleghenies."[6] Pond scored the first touchdown in University of Michigan history in the match.[7][8] He scored the touchdown midway through "the first 'inning'."[9] According to Will Perry's history of Michigan football, the crowd responded to Pond's plays with cheers of "Pond Forever."[6] Pond graduated from Michigan in 1879 with a degree in civil engineering.[2]

Architect

Early career

In 1879, Pond moved to Chicago to pursue a career as an architect. He worked as a draftsman in the offices of his former teacher, William LeBaron Jenney, and worked as the head draftsman in the office of Solon Spencer Beman during the construction of the planned Pullman community.[4] While working with Beman, Pond was an ardent supporter of the Pullman planned community, he later acknowledged the resentment of Pullman residents that the town was anachronistic and represented some form of medieval barony.[10][11]

Some of Pond's earliest works as an independent architect were for clients in his home town of Ann Arbor and nearby Detroit. As early as 1882, he designed "a modest but commodious home of stone and brick" on South State Street for Dr. Victor C. Vaughan. Pond later pointed to the designs of the old mantels in the Vaughan house which "foreshadowed his future works."[12] He also designed Ann Arbor's Ladies Library Association Building (1885) and the West Physics Building for the University of Michigan, built in 1887 and destroyed by fire in 1967.[13] In 1887, he renovated the Detroit Opera House, increasing the seating capacity to 2,100 and relocating the auditorium to the main floor.[14]

In 1886, Pond and his brother Allen Bartlitt Pond (1858–1929) formed their own architectural firm in Chicago under the name Pond and Pond.[1][2] The brothers continued to operate the firm for more than 40 years, and their buildings are considered to be among the best examples of Arts and Crafts architecture in Chicago.[15]

Hull House and settlement house movement

The Pond brothers gained their greatest acclaim as the architects for Jane Addams's Hull House. Their father's work as warden of the state prison had sparked an interest in social reform and the settlement house movement. Allen Bartlitt Pond was the assistant superintendent of the Armour Mission,[16] an educational and healthcare center, when Jane Addams came to Chicago in January 1889 looking for a building in which to open a new settlement house.[17] The two became friends and were riding in a carriage when Addams saw an old two-story brick house on Halsted Street.[18] Addams took a lease on the house, which she named Hull House after its original owner, and hired the Ponds to put the old house into shape.[19][20]

Between 1890 and 1907, the Ponds were the architects for the Hull House as the project expanded rapidly.[21] The first building they designed for Hull House was the Butler Art Gallery. Built in 1891, the Butler Gallery was situated on the same lot as Hull House. It consisted of a reading room, an exhibition hall that was "the last word in design and lighting for those days," and a studio above.[20] Numerous other building projects followed, including the original coffee house and gymnasium in 1893, the Children's Building in 1895, remodels and additions to the original building in 1895 and 1899, the Jane Club in 1898, a new Coffee House and Hull House Theater in 1899, the Hull House Apartments and Men's Club in 1901 and 1902, the Woman's Club (Bowen Hall) in 1904, the Boys' Club in 1906 and the Mary Crane Nursery in 1907.[22] The Pond brothers were affectionately known by residents of the Hull House complex as Allen the "deep Pond" and Irving the "wide pond."[23]

One of Addams' biographers wrote that the "Pond brothers did it all, harmonized everything," and described the scene when Irving Pond attended Addams' memorial service in 1935:

Irving K., at Jane Addams memorial services in the Hull House Court, when Doctor Gilkey said, 'if you seek her monument look around you,' looked round also with tears in his eyes but pride in his heart; the visible memorial to Jane Addams was also a visible memorial to the Ponds.[24]

The only surviving building from the Ponds' Hull House complex is the 1905 dining hall, a simple Craftsman style building that was designated as a National Historic Landmark in the 1960s.[25][26]

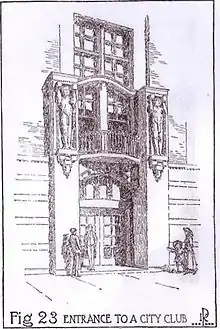

The Ponds also designed club houses and settlement houses for other social reform organizations, including the Chicago Commons settlement house building (1901), the Northwestern University Settlement House (1901), and the City Club of Chicago building (1910). The City Club building, noted for its "gently curving limestone arch that ties together the windows of the second floor," is today operated as the John Marshall Law School.[27] When the City Club building opened in 1910, it was considered a symbol of the reform movement:

The new building embodied the soaring expectations of the reform movement, as well as providing the material comforts of a middle-class social club. Its two-story dining-lecture hall, complete with balcony and private eating chambers, accommodated over two hundred for the weekly luncheon talks on social and political issues of the day. ... Architect and club member Irving K. Pond declared that 'every line of the building illustrated some phase of the uplift movement.'[28]

Eagle's Nest and related activities

Pond was also a leading member of the Chicago arts community in the late 19th and early 20th Century. In 1898, Pond was one of the founders of the Eagle's Nest Art Colony near Oregon, Illinois.[29] Pond and eleven others, including his brother Allen Pond, Lorado Taft, Hamlin Garland, Ralph Clarkson, Horace Spencer Fiske, leased a plot of land on a steep ridge with "craggy rocks" and gnarled cedars overlooking the Rock River.[30] The Pond brothers designed the home that was built for the colony, and the group spent their summers at the colony with other sculptors, painters, writers, architects, naturalists and kindred spirits.[30]

The artists colony became integrated with the Oregon community, and the Pond brothers undertook several significant architectural projects in the Oregon area:

- Oregon Public Library. In 1908, the city of Oregon built a new public library based on a design by Pond and Pond and with funding from Andrew Carnegie. The Ponds' design has been described as having a "commodious and pleasing" interior with an exterior of white brick and Elizabethan-Gothic architecture.[31] One of the unusual features of the design was a two-story art room in which artists from Eagle's Nest displayed their works and offered instruction to local residents.[32]

- The Soldier's Monument. In 1916, the city commissioned a monument that included sculpture by Lorado Taft and an elaborate marble exedra by Pond and Pond.[33]

- Lowden Residence. The residence of Frank Lowden, Governor of Illinois from 1917 to 1921, was another Pond and Pond design. The house is located several miles south of Oregon on the Sinnissippi Farm.[34]

In 1907, Pond was also one of the founders with Hamlin Garland of the Cliff Dwellers Club (originally known as the Attic Club and later the Little Room), a private club in Chicago for professionals engaged in the fine arts and performing arts. In its early years as the Little Room, the group was described as "an exclusive organization consisting of creative individuals of like temperament joined together for relaxation."[35] Pond served as president of the Cliff Dwellers from 1934 to 1935.[4]

Professional organizations

In recognition of his contributions to architecture, Pond became a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1900 and served as president of the American Institute of Architects from 1910 to 1911.[2] He also represented the U.S. government and the AIA at the International Congress of Architects at Rome and Venice in 1911, delivering addresses at both.[1] He was also a founder of the Chicago Architectural Club and served as president of the Illinois Society of Architects.[1]

Notable commissions

- Unless otherwise mentioned all were designed by Pond and Pond

Pond's best known buildings include three National Historic Landmark structures located in Chicago — the Hull House dining hall[25][26] the Lorado Taft Midway Studios,Alice Sinkevitch (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 452. ISBN 0-15-602908-1.[36] and the Frank R. Lillie House (1904).[37][38] Other notable Pond designs include the Freer House (1898) in Ann Arbor, the American School of Correspondence building (1906–1907) in Chicago, the federal building in Kankakee, Illinois, the Michigan Union (1919) built on the site of Pond's boyhood home in Ann Arbor,[39] the Purdue Memorial Union (1924) at Purdue University, the MSU Union in East Lansing, Michigan, the Kansas Memorial Union at the University of Kansas, the Park Ridge Public Library, the Michigan League in Ann Arbor, the Omaha Apartments in Chicago, the Kent Building in Chicago (1902), and the Toll Building in Chicago (1908).[40]

Architectural style and philosophy

As early as 1892, Pond became known as one of the "earliest modernizers in architecture."[41] The Art Institute of Chicago, where Pond's papers are housed, said of the firm: "While Pond and Pond were best known through their work for social service organizations, they designed a wide range of buildings — social, religious, educational/academic, residential, governmental, and civic — mainly in the Chicago area and the Midwest. They were known for detailed brickwork, asymmetrical massing, and distinctive decorative detail, producing fine examples of Arts and Crafts and early modern architecture."[21]

In 1905 a 15-page article in the Architectural Record by Pond and illustrated by his designs was published.[42] Pond described his views in it about architecture as an art:

Architecture is an art, and as an art, it does not consist simply in piling up forms, old or new, but is a means of expression. ... If architecture is an art and art consists in the expression of life, then that is neither architecture nor art which merely reproduces, even in new combinations, the old forms because they were once the accepted forms. That is a phase of archaeology and is unworthy of living architecture. ... However, the old ideas are not to be spurned and the old forms are not altogether to be cast aside when they contain the spark of life ...[42]

Pond's article was viewed by some as a criticism of those in the Prairie School who overemphasized the horizontal over the vertical. In this regard, Pond wrote:

In architectural composition, as in music, order is comprehended in rhythm. Rhythm is expressed in the flow of part into part, of mass into mass, in the appearance and reappearance of certain proportions which are made to exist between the subordinate masses and between these masses and the dominant mass; between all the parts of the perfect whole. Without order there is no architecture; without rhythmic composition no vital architecture can be. That is the highest architecture in which rhythmic action of the structural forces becomes apparent. Vertical forces in action, by the law of gravity, tend to work in right lines; horizontal forces, acted upon by this same law tend to work in curves. ... It is not enough that the rhythmic movement be in horizontal direction only, but there must be a rhythmic flow vertically as well. The result of these combined movements should be that of unity -- simple in its effect though complex in its harmonies.[42]

Role in the Chicago school

In the AIA Guide to Chicago, the Ponds are identified as part of the "circle of young architects", including Frank Lloyd Wright, that was responsible for "transforming the concepts of the Arts & Crafts movement into the indigenous Prairie School."Alice Sinkevitch (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 272. ISBN 0-15-602908-1. Pond was a contemporary, and in some ways rival, of Wright in the Chicago architectural scene of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. Both were members of the Chicago Architectural Club and served as judges and participants in the Club's annual competitions.[43] One biographer of Wright noted that Wright was insulted when the American Institute of Architects in 1912 commissioned a study of midwestern "progressive architecture" and instructed the investigators to examine the work of Louis Sullivan and Pond, but not including Wright.[44] In a letter to Lewis Mumford, Wright expressed his dislike for the "truly-old" Pond:

Yesterday someone told me that truly-old I.K. Pond took exception to your 'Sticks and Stones' because you weren't a 'practicing architect.' What 'practicing architects' know anything at all of architecture anyway, -- even if they could write about it? Certainly not he. He's a dried herring, hanging beneath the eaves or Architecture.[45]

While progressive in his approach to architecture, Pond was not as revolutionary as others in the Chicago school of his day. Architect Stuart Cohen, FAIA, noted that, while the Pond brothers' architecture departs from traditional architectural styles, they "did not break radically from such stylistic forms" but sought instead "to create a modern American architecture without rejecting architectural stylistic traditions, but simplifying them through the emphasis of geometry and the inherent quality of building materials and construction."[46]

In 2009, Pond's autobiography, written in the two years before his death, was published by Hyoogen Press through the efforts of Chicago architect David Swan.[46] At the time of the autobiography's release, architecture historian Robert Bruegmann opined that the Pond brothers "have remained relatively obscure because they didn't fit in with narratives that wished to see Chicago architecture of the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a prelude to European modernism of the 1920s."[46] Nevertheless, Bruegmann noted that "Chicago architecture was always a great deal more than that" and expressed his satisfaction that the publication of Pond's autobiography "should go a long way toward bringing back into focus one of America's most interesting and important architectural practices."[46]

Author

Pond was a noted author and member of the Chicago Literary Club from 1888 to 1939. He was the club's president from 1922 to 1923.[47] Many of his works of fiction, poems and papers on art and architecture were published by the club, including "A Strange Fellow: A Story with an Immoral" (1889),[48] "The Mystery of the Light" (1891),[49] "The Pleasures of Travel (1894),[50] "Can Architecture Become Again a Living Art?" (1895), "The Whale - A Study: The Historic School of Jonah" (1897),[51] "The Poetry of Motion: and Other Matters" (1899), "A Few Meloncholy Reflections and Lively Anticipations of Misdeeds to Come" (1905), "A Side Light on Architecture" (1906), "Art and the Expression of Individuality" (1911), "Architecture: Its Origins and Illusions" (1914),"Poems" (1917), "Here Lies the Way" (1918), "Such Stuff as Dreams Are Made On."[52] "The Stones of Venice" (1919), "A Day Under the Big Top: A Study in Life and Art" (1924),[53] "On Believing and Leaving" (1928),[54] "Toward an American Architecture" (1930), "Hold Your Horses: The Elephants Are Coming!" (1931), "What Is Modern Architecture?" (1933), "Just One Thing After Another" (1934), and "Do Children Think?" (1938).[55][56]

Pond was also a frequent contributor to architectural journals and wrote for The Dial.[1] In 1910, he published an essay in Gustav Stickley's The Craftsman, advocating an architectural style embodying the American spirit and idealism.[57] In 1918, he published the book The Meaning of Architecture.[58]

In 1908, Pond's 13-page article on the architecture of telephone exchange buildings, illustrated by the designs of Pond and Louis Sullivan, also appeared in Architectural Record.[59]

- Books by Pond

- The Meaning Of Architecture: An Essay In Constructive Criticism (1918)

- The College Union (1931)

- Big Top Rhythms: A Study in Art and Life, written and illustrated by Pond (1937)

- A Strange Fellow, and other Club Papers, written and illustrated by Pond (1938)

- The Autobiography of Irving K. Pond, written in the 1930s and published posthumously (2009)

Later years

Pond was a bachelor until age 72. Through most of his life, his closest friend was his brother Allen Pond. In 1918, he wrote the following in the dedication to his book, The Meaning of Architecture:

This book is dedicated to my brother -- my lifelong companion and partner Allen Bartlit Pond. Through his sympathy and understanding, in the light of his clear thought, and under his inspiration I have been better able to follow those paths of individual, professional and civic endeavor in which a rare ancestry bade us walk.[58]

After his brother died in 1929, Pond married Katherine N. de Nancrede, who was 47 years old, at a ceremony in Ann Arbor.[7] Pond said at the time, "It's the first time I ever did it, and I thought I ought to be pardoned because of my youth."[7][8] Pond was also an amateur acrobat and remained a physical fitness buff all of his life. At the time of his wedding in 1929, the Associated Press reported that he is "almost as well known for his present athletic agility as for his architectural accomplishments. A part of his daily routine is to turn handsprings and flipflops and do other strenuous exercises."[7] He drew applause when, on his 80th birthday, he grabbed his bare knees with both hands and performed a backflip. A photograph of Pond's feat was published in Life magazine in June 1937.[60]

Though he was some 25 years older than his wife, Pond outlived her. She died in 1935, and Pond died four years later in September 1939 while traveling in Washington, D.C.[61] The cause of death was reported as a stomach ulcer.[61] He was age 82 when he died, and he asked that his remains be cremated and sent to the University of Michigan.[61]

Gallery of buildings designed by Pond and Pond

.jpg.webp) Michigan Union

Michigan Union Chicago Commons

Chicago Commons Hull House Coffee Room

Hull House Coffee Room John Shanklin House, Evansville, Indiana

John Shanklin House, Evansville, Indiana Northwestern University Settlement House

Northwestern University Settlement House Residence of Prof. J.W. Thompson

Residence of Prof. J.W. Thompson Hull House Women's Club

Hull House Women's Club W.F. Dummer Residence, Coronado, California

W.F. Dummer Residence, Coronado, California

References

- Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Homans, James E., ed. (1918). . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: The Press Association Compilers, Inc. p. 121.

Homans, James E., ed. (1918). . The Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: The Press Association Compilers, Inc. p. 121. - 1 2 3 4 Irving Kane Pond: A Biographical Sketch. James T. White & Co. 1922.

- ↑ Earl D. Babst; Lewis George Vander Velde (1948). Michigan and the Cleveland Era. University of Michigan Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-8369-8092-1.

- 1 2 3 "Irving Kane Pond biography". Chicago Literary Club. 1999.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1936). Neither a Skyscraper nor of Skeleton Construction. Architectural Record.

- 1 2 Perry, Will (1974). The Wolverines: A Story of Michigan Football. The Strode Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 0-87397-055-1.

- 1 2 3 4 "IRVING POND, YOUTH OF 72 YEARS, IS WED". The News-Palladium (AP story). 1929-06-12.

- 1 2 "Milestones". Time. 1929-06-24. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010.

- ↑ Perry, Will (1974). The Wolverines: A Story of Michigan Football. The Strode Publishers. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-87397-055-1.

- ↑ Almont Lindsey (1942). The Pullman Strike. University of Chicago Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-226-48383-5.

- ↑ Irving Pond (June–July 1934). Pullman -- America's First Planned Independent Town. Illinois Society of Architect's Monthly Bulletin. pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Victor C. Vaughan. A Doctor's Memories. p. 155.

- ↑ "Physics Building". University of Michigan.

- ↑ Michael Hauser; Marianne Weldon (2006). Detroit's Downtown Movie Palaces. Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 0-7385-4102-8.

- ↑ "Swan on Pond at AIA". Society of Architectural Historians. 11 December 2009.

- ↑ Louise K. Knight (2005). Citizen: Jane Addams and the Struggle for Democracy. University of Chicago Press. p. 195. ISBN 0-226-44699-9.

- ↑ Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-252-06904-8.

- ↑ Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 92. ISBN 0-252-06904-8..

- ↑ Louise K. Pond, Citizen, pp. 195-196

- 1 2 Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-252-06904-8.

- 1 2 "Finding aid for the Pond and Pond Collection". Ryerson and Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26.

- ↑ Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 209. ISBN 0-252-06904-8.

- ↑ Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 191. ISBN 0-252-06904-8.

- ↑ Jams Weber Linn; Anne Firor Scott (2000). Jane Addams: A Biography. University of Illinois Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-252-06904-8.

- 1 2 Alice Sinkevitch (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 302. ISBN 0-15-602908-1.

- 1 2 "Jane Addams' Hull-House: Humanities Programs for the Centennial 1989-1990". Institute for the Humanities.

- ↑ Alice Sinkevitch (2004). AIA Guide to Chicago. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 62. ISBN 0-15-602908-1.

- ↑ Andrew Feffer (1993). The Chicago Pragmatists and American Progressivism. Cornell University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-8014-2502-6.

- ↑ Lorado Taft Campus, NIU Historical Buildings: Lorado Taft Field Campus Historical Significance, Northern Illinois University. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- 1 2 Newton Bateman; Paul Selby; Horace Kauffman; Rebecca Kauffman, eds. (1917). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, volume 2. Munsell Publishing Company. p. 711.

- ↑ Newton Bateman; Paul Selby; Horace Kauffman; Rebecca Kauffman, eds. (1917). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, volume 2. Munsell Publishing Company. p. 808.

- ↑ Newton Bateman; Paul Selby; Horace Kauffman; Rebecca Kauffman, eds. (1917). Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois, volume 2. Munsell Publishing Company. p. 712.

- ↑ Jan Stilson (2006). Art and Beauty in the Heartland: The Story of the Eagle's Nest Art Camp at Oregon, Illinois. AuthorHouse. p. 103. ISBN 1-4259-3866-3.

- ↑ Jan Stilson (2006). Art and Beauty in the Heartland: The Story of the Eagle's Nest Art Camp at Oregon, Illinois. AuthorHouse. p. 31. ISBN 1-4259-3866-3.

- ↑ Timothy Joseph Garvey (1988). Public Sculptor: Lorado taft and the Beautification of Chicago. University of Illinois Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-252-01501-0.

- ↑ "Taft, Lorado, Midway Studios". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ "Frank R. Lillie House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2008-01-03. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ James Sheire (January 27, 1976), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Frank R. Lillie House (pdf), National Park Service and Accompanying 1 photo, exterior, from 1975. (432 KB)

- ↑ Susan Cee Wineberg (2004). Lost Ann Arbor. Arcadia Publishing. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7385-3339-1.

- ↑ Carl W. Condit (1964). The Chicago School of Architecture: A History of Commercial and Public Building in the Chicago Area, 1875-1925. University of Chicago Press. p. 205. ISBN 0-226-11455-4.

- ↑ Industrial Chicago: The Building Interests. The Goodspeed Publishing Company. 1891.

- 1 2 3 Irving K. Pond (1905). "The Life of Architecture". Architectural Record. pp. 146–160.

- ↑ Robert C. Twombly (1987). Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and His Architecture. Wiley IEEE. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-471-85797-1.

- ↑ Twombly 1987, p. 163.

- ↑ Bruce Brooks, ed. (1987). Frank Lloyd Wright & Lewis Mumford: Thirty Years of Correspondence. Wiley IEEE. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-471-85797-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Irving K. Pond (2009). The Autobiography of Irving K. Pond. Hyoogen Press. ISBN 978-0-9818330-1-9.

- ↑ "Officers of the Club and Members of the Board of Directors". Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1889). A Strange Fellow: A Story with an Immoral (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1891). The Mystery of the Light (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1894). The Pleasures of Travel (PDF). Chicgago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1897). The Whale - A Study: The Historic School of Jonah (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond. Book Night: Such Stuff as Dreams Are Mad On (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1924). A Day Under the Big Top: A Study in Life and Art (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond. On Believing and Leaving (PDF). Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ "Index of Papers Online". Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ "Member Biographies". Chicago Literary Club.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1910). Let Us Embody the American Spirit in our Architecture. The Craftsman. p. 67.

- 1 2 Irving K. Pond (1918). The Meaning of Architecture.

- ↑ Irving K. Pond (1905). "The Telephone Exchange". Architectural Record. pp. 258–270.

- ↑ Life, June 14, 1937, p. 28

- 1 2 3 "IRVING K. POND, ARCHITECT AND WIT, DIES AT 82: Famous as Speaker and Athlete". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1939-09-30. Retrieved 2010-04-29.