In linguistics, inversion is any of several grammatical constructions where two expressions switch their canonical order of appearance, that is, they invert. There are several types of subject-verb inversion in English: locative inversion, directive inversion, copular inversion, and quotative inversion. The most frequent type of inversion in English is subject–auxiliary inversion in which an auxiliary verb changes places with its subject; it often occurs in questions, such as Are you coming?, with the subject you is switched with the auxiliary are. In many other languages, especially those with a freer word order than English, inversion can take place with a variety of verbs (not just auxiliaries) and with other syntactic categories as well.

When a layered constituency-based analysis of sentence structure is used, inversion often results in the discontinuity of a constituent, but that would not be the case with a flatter dependency-based analysis. In that regard, inversion has consequences similar to those of shifting.

In English

In broad terms, one can distinguish between two major types of inversion in English that involve verbs: subject–auxiliary inversion and subject–verb inversion.[1] The difference between these two types resides with the nature of the verb involved: whether it is an auxiliary verb or a full verb.

Subject–auxiliary inversion

The most frequently occurring type of inversion in English is subject–auxiliary inversion. The subject and auxiliary verb invert (switch positions):

- a. Fred will stay.

- b. Will Fred stay? - Subject–auxiliary inversion with yes/no question

- a. Larry has done it.

- b. What has Larry done? - Subject–auxiliary inversion with constituent question

- a. Fred has helped at no point.

- b. At no point has Fred helped. - Subject–auxiliary inversion with fronted expression containing negation (negative inversion)

- a. If we were to surrender, ...

- b. Were we to surrender, ... - Subject–auxiliary inversion in condition clause

The default order in English is subject–verb (SV), but a number of meaning-related differences (such as those illustrated above) motivate the subject and auxiliary verb to invert so that the finite verb precedes the subject; one ends up with auxiliary–subject (Aux-S) order. That type of inversion fails if the finite verb is not an auxiliary:

- a. Fred stayed.

- b. *Stayed Fred? - Inversion impossible here because the verb is NOT an auxiliary verb

(The star * is the symbol used in linguistics to indicate that the example is grammatically unacceptable.)

Subject–verb inversion

In languages like Italian, Spanish, Finnish, etc. subject-verb inversion is commonly seen with a wide range of verbs and does not require an element at the beginning of the sentence. See the following Italian example:

è

is

arrivato

arrived

Giovanni.

Giovanni

'Giovanni arrived'

In English, on the other hand, subject-verb inversion generally takes the form of a Locative inversion. A familiar example of subject-verb inversion from English is the presentational there construction.

There's a shark.

English (especially written English) also has an inversion construction involving a locative expression other than there ("in a little white house" in the following example):

In a little white house lived two rabbits.[2]

Contrary to the subject-auxiliary inversion, the verb in cases of subject–verb inversion in English is not required to be an auxiliary verb; it is, rather, a full verb or a form of the copula be. If the sentence has an auxiliary verb, the subject is placed after the auxiliary and the main verb. For example:

- a. A unicorn will come into the room.

- b. Into the room will come a unicorn.

Since this type of inversion generally places the focus on the subject, the subject is likely to be a full noun or noun phrase rather than a pronoun. Third-person personal pronouns are especially unlikely to be found as the subject in this construction:

- a. Down the stairs came the dog. - Noun subject

- b. Down the stairs came it. - Third-person personal pronoun as subject; unlikely unless it has special significance and is stressed

- c. Down the stairs came I. - First-person personal pronoun as subject; more likely, though still I would require stress

In other languages

Certain other languages, like other Germanic languages and Romance languages, use inversion in ways broadly similar to English, such as in question formation. The restriction of inversion to auxiliary verbs does not generally apply in those languages; subjects can be inverted with any type of verb, but particular languages have their own rules and restrictions.

For example, in French, tu aimes le chocolat is a declarative sentence meaning "you like the chocolate". When the order of the subject tu ("you") and the verb aimes ("like") is switched, a question is produced: aimes-tu le chocolat? ("do you like the chocolate?"). In German, similarly, du magst means "you like", whereas magst du can mean "do you like?".

In languages with V2 word order, such as German, inversion can occur as a consequence of the requirement that the verb appear as the second constituent in a declarative sentence. Thus, if another element (such as an adverbial phrase or clause) introduces the sentence, the verb must come next and be followed by the subject: Ein Jahr nach dem Autounfall sieht er wirklich gut aus, literally "A year after the car accident, looks he really good". The same occurs in some other West Germanic languages, like Dutch, in which this is Een jaar na het auto-ongeval ziet hij er werkelijk goed uit. (In such languages, inversion can function as a test for syntactic constituency since only one constituent may surface preverbally.)

In languages with free word order, inversion of subject and verb or of other elements of a clause can occur more freely, often for pragmatic reasons rather than as part of a specific grammatical construction.

Locative inversion

Locative inversion is a common linguistic phenomenon that has been studied by linguists of various theoretical backgrounds.

In multiple Bantu languages, such as Chichewa,[3] the locative and subject arguments of certain verbs can be inverted without changing the semantic roles of those arguments, similar to the English subject-verb inversion examples above. Below are examples from Zulu,[4] where the numbers indicate noun classes, SBJ = subject agreement prefix, APPL = applicative suffix, FV = final vowel in Bantu verbal morphology, and LOC is the locative circumfix for adjuncts.

- Canonical word order:

A-bantwana

2-2.child

ba-fund-el-a

2.SBJ-study-APPL-FV

e-sikole-ni.

LOC:7-7.school-LOC

"The children study at the school."

- Locative inversion:

I-sikole

7-7.school

si-fund-el-a

7.SBJ-study-APPL-FV

a-bantwana.

2-2.child

"The children study at the school." (lit. "The school studies the children.")

In the locative inversion example, isikole, "school" acts as the subject of the sentence while semantically remaining a locative argument rather than a subject/agent one. Moreover, we can see that it is able to trigger subject-verb agreement as well, further indicating that it is the syntactic subject of the sentence.

This is in contrast to examples of locative inversion in English, where the semantic subject of the sentence controls subject-verb agreement, implying that it is a dislocated syntactic subject as well:

- Down the hill rolls the car.

- Down the hill roll the cars.

In the English examples, the verb roll agrees in number with cars, implying that the latter is still the syntactic subject of the sentence, despite being in a noncanonical subject position. However, in the Zulu example of locative inversion, it is the noun isikole, "school" that controls subject-verb agreement, despite not being the semantic subject of the sentence.

Locative inversion is observed in Mandarin Chinese. Consider the following sentences:

- Canonical word order

Gǎngshào

Sentry

zhàn

stand

zài

at

ménkǒu.

door

'At the entrance stands a/the sentry'

- Locative inversion

In canonical word order, the subject (gǎngshào 'sentry') appears before the verb and the locative expression (ménkǒu 'door') after the verb. In Locative inversion, the two expressions switch the order of appearance: it is the locative that appears before the verb while the subject occurs in postverbal position. In Chinese, as in many other languages, the inverted word order carry a presentational function, that is, it is used to introduce new entities into discourse.[6]

Theoretical analyses

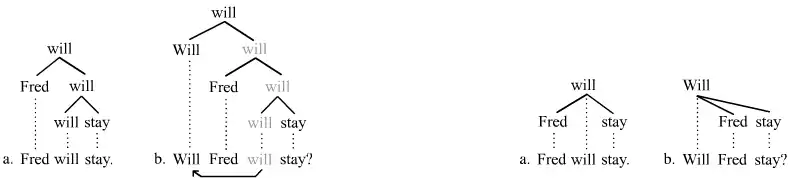

Syntactic inversion has played an important role in the history of linguistic theory because of the way it interacts with question formation and topic and focus constructions. The particular analysis of inversion can vary greatly depending on the theory of syntax that one pursues. One prominent type of analysis is in terms of movement in transformational phrase structure grammars.[7] Since those grammars tend to assume layered structures that acknowledge a finite verb phrase (VP) constituent, they need movement to overcome what would otherwise be a discontinuity. In dependency grammars, by contrast, sentence structure is less layered (in part because a finite VP constituent is absent), which means that simple cases of inversion do not involve a discontinuity;[8] the dependent simply appears on the other side of its head. The two competing analyses are illustrated with the following trees:

The two trees on the left illustrate the movement analysis of subject-auxiliary inversion in a constituency-based theory; a BPS-style (bare phrase structure) representational format is employed, where the words themselves are used as labels for the nodes in the tree. The finite verb will is seen moving out of its base position into a derived position at the front of the clause. The trees on the right show the contrasting dependency-based analysis. The flatter structure, which lacks a finite VP constituent, does not require an analysis in terms of movement but the dependent Fred simply appears on the other side of its head Will.

Pragmatic analyses of inversion generally emphasize the information status of the two noncanonically-positioned phrases – that is, the degree to which the switched phrases constitute given or familiar information vs. new or informative information. Birner (1996), for example, draws on a corpus study of naturally-occurring inversions to show that the initial preposed constituent must be at least as familiar within the discourse (in the sense of Prince 1992) as the final postposed constituent – which in turn suggests that inversion serves to help the speaker maintain a given-before-new ordering of information within the sentence. In later work, Birner (2018) argues that passivization and inversion are variants, or alloforms, of a single argument-reversing construction that, in turn, serves in a given instance as either a variant of a more general preposing construction or a more general postposing construction.

The overriding function of inverted sentences (including locative inversion) is presentational: the construction is typically used either to introduce a discourse-new referent or to introduce an event which in turn involves a referent which is discourse-new. The entity thus introduced will serve as the topic of the subsequent discourse.[9] Consider the following spoken Chinese example:

Zhènghǎo

Just

tóuli

ahead

guò-lai

pass-come

yí

one-CL

lǎotóur,

old-man

'Right then came over an old man.'

zhè

this

lǎotóur,

old.man

tā

3S

zhàn-zhe

stand-DUR

hái

still

bù

not

dònghuó

move

'this old man, he was standing without moving.' [10]

The constituent yí lǎotóur "an old man" is introduced for the first time into discourse in post-verbal position. Once it is introduced by the presentational inverted structure, it can be coded by the proximal demonstrative pronoun zhè 'this' and then by the personal pronoun tā – denoting an accessible referent: a referent that is already present in speakers' consciousness.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The use of terminology here, subject-auxiliary inversion and subject–verb inversion, follows Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:410).

- ↑ Birner, Betty Jean (1994). "Information status and word order: an analysis of English inversion". Language. 2 (70): 233–259. doi:10.2307/415828. JSTOR 415828.

- ↑ Bresnan, Joan (1994). "Locative Inversion and Architecture of Universal Grammar". Language. 70 (1): 72–131. doi:10.2307/416741. JSTOR 416741.

- ↑ Buell, Leston Chandler (2005). "Issues in Zulu Morphosyntax". PhD Dissertation, UCLA.

- ↑ Shen 1987, p. 197.

- ↑ Lena, L. 2020. Chinese presentational sentences: the information structure of Path verbs in spoken discourse". In: Explorations of Chinese Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- ↑ The movement analysis of subject-auxiliary inversion is pursued, for instance, by Ouhalla (1994:62ff.), Culicover (1997:337f.), Radford (1988: 411ff., 2004: 123ff).

- ↑ Concerning the dependency grammar analysis of inversion, see Groß and Osborne (2009: 64-66).

- ↑ Lambrecht, K., 2000. When subjects behave like objects: An analysis of the merging of S and O in sentence-focus constructions across languages. Studies in Language, 24(3), pp.611-682.

- ↑ Lena 2020, ex. 10.

References

- Birner, B. 2018. On constructions as a pragmatic category. Language 94.2:e158-e179.

- Birner, B. 1996. The discourse function of inversion in English. Outstanding Dissertations in Linguistics. NY: Garland.

- Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Greenbaum, S. and R. Quirk. 1990. A student's grammar of the English language. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43-90.

- Lena, Ludovica (2020). "Chinese presentational sentences: the information structure of Path verbs in spoken discourse". In Chen, Dongyan; Bell, Daniel (eds.). Explorations of Chinese Theoretical and Applied Linguistics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-5994-3.

- Ouhalla, J. 1994. Transformational grammar: From rules to principles and parameters. London: Edward Arnold.

- Prince, E. F. 1992. The ZPG letter: Subjects, definiteness, and information-status. In W. C. Mann and S. A. Thompson, Discourse description: Diverse linguistic analyses of a fundraising text. Philadelphia: John Benjamins. 295-325.

- Shen, J. (1987). "Subject function and double subject construction in mandarin Chinese". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 16 (2): 195–211. doi:10.3406/clao.1987.1229.

- Quirk, R. S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1979. A grammar of contemporary English. London: Longman.

- Radford, A. 1988. Transformational Grammar: A first course. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Radford, A. 2005. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

External links

Media related to Inversion (linguistics) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Inversion (linguistics) at Wikimedia Commons