| Peritoneal dialysis | |

|---|---|

Diagram of peritoneal dialysis | |

| Specialty | nephrology |

| ICD-9-CM | 54.98 |

| MeSH | D010530 |

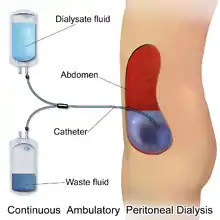

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a type of dialysis that uses the peritoneum in a person's abdomen as the membrane through which fluid and dissolved substances are exchanged with the blood.[1][2] It is used to remove excess fluid, correct electrolyte problems, and remove toxins in those with kidney failure.[3] Peritoneal dialysis has better outcomes than hemodialysis during the first couple of years.[4] Other benefits include greater flexibility and better tolerability in those with significant heart disease.[4]

Side effects

Complications may include infections within the abdomen, hernias, high blood sugar, bleeding in the abdomen, and blockage of the catheter.[3] Peritoneal dialysis is not possible in those with significant prior abdominal surgery or inflammatory bowel disease.[3] It requires some degree of technical skill to be done properly.[4]

Mechanism

In peritoneal dialysis, a specific solution is introduced through a permanent tube in the lower abdomen and then removed.[3] This may either occur at regular intervals throughout the day, known as continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), or at night with the assistance of a machine, known as automated peritoneal dialysis (APD).[3] The solution is typically made of sodium chloride, bicarbonate, and an osmotic agent such as glucose.[3]

History and culture

The solution used for peritoneal dialysis is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5][6] As of 2009, peritoneal dialysis was available in 12 of 53 African countries.[7]

Medical uses

Peritoneal dialysis is a method of renal replacement therapy for needing maintenance therapy for late stage chronic kidney disease and is an alternative to the most common method hemodialysis.

Complications

Peritoneal Dialysis-Related Peritonitis

A common cause of peritonitis is touch contamination, e.g. insertion of catheter by un-sanitized hands, which potentially introduces bacteria to the abdomen; other causes include catheter complication, transplantation of bowel bacteria, and systemic infections.[8] Most common type of PD-peritonitis infection (80%) are from bacterial sources.[8] Infection rates are highly variable by region and within centers with estimated rates between 0.06 - 1.66 episodes per patient year.[9] With recent technical advances peritonitis incidence has decreased over time.[10]

Antibiotics are needed if the source of infection is bacterial; there is no clear advantage for other frequently used treatments such as routine peritoneal lavage or use of urokinase.[11] The use of preventative nasal mupirocin is of unclear effect with respect to peritonitis.[12] Of the three types of connection and fluid exchange systems (standard, twin-bag and y-set; the latter two involving two bags and only one connection to the catheter, the y-set uses a single y-shaped connection between the bags involving emptying, flushing out then filling the peritoneum through the same connection) the twin-bag and y-set systems were found superior to conventional systems at preventing peritonitis.[13]

The fluid used for dialysis uses glucose as a primary osmotic agent. According to a 2020 review published in the American Journal of Nephrology, some studies suggest that the use of glucose increases the risk of peritonitis, possibly as a result of impaired host defenses, vascular disease, or damage to the peritoneal membrane.[14] The acidity, high concentration and presence of lactate and products of the degradation of glucose in the solution (particularly the latter) may contribute to these health issues. Solutions that are neutral, use bicarbonate instead of lactate and have few glucose degradation products may offer more health benefits though this has not yet been studied.[15]

The mortality rate of peritoneal dialysis related peritonitis is estimated to be 3-10%, with approximately 50% of cases resulting in hospitalization.[16] Peritoneal fluid studies with a white blood cell count greater than 100 per μL and greater than 50% neutrophils strongly suggest peritonitis, with a definitive diagnosis based on culture of microorganisms from the peritoneal fluid.[16] In order to avoid delaying treatment, a cloudy fluid in the dialysate fluid can be assumed to be due to peritonitis unless an alternative cause is identified.[16] Peritonitis in those undergoing PD is usually due to gram positive bacteria.[16] Intraperitoneal antibiotics are preferred to intravenous as they have a greater effect at the area of infection, unless sepsis is present, in which case intravenous antibiotics are indicated.[16] The peritoneal dialysis catheter may have to be removed if the infection does not resolve with antibiotics, and it is recommended that the PD catheter be removed in all cases of fungal peritonitis.[16]

Volume Shifts

The volume of dialysate removed as well as patient's weight are monitored. If more than 500ml of fluid are retained or a liter of fluid is lost across three consecutive treatments, the patient's physician is generally notified . Excessive loss of fluid can result in hypovolemic shock or hypotension while excessive fluid retention can result in hypertension and edema. Also monitored is the color of the fluid removed: normally it is pink-tinged for the initial four cycles and clear or pale yellow afterward. The presence of pink or bloody effluent suggests bleeding inside the abdomen while feces indicates a perforated bowel and cloudy fluid suggests infection. The patient may also experience pain or discomfort if the dialysate is too acidic, too cold or introduced too quickly, while diffuse pain with cloudy discharge may indicate an infection. Severe pain in the rectum or perineum can be the result of an improperly placed catheter. The dwell can also increase pressure on the diaphragm causing impaired breathing, and constipation can interfere with the ability of fluid to flow through the catheter.[17]

Chronic Complications

Long term use of PD is rarely associated with fibrosis of the peritoneum.[10] A potentially fatal complication estimated to occur in roughly 2.5% of patients is encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis, in which the bowels become obstructed due to the growth of a thick layer of fibrin within the peritoneum.[18]

Other

Other complications include low back pain and hernia or leaking fluid due to high pressure within the abdomen.[19] Hypertriglyceridemia and obesity are also concerns due to the large volume of glucose in the fluid, which can add 500-1200 calories to the diet per day.[20]

Method

Best practices for peritoneal dialysis state that before peritoneal dialysis should be implemented, the person's understanding of the process and support systems should be assessed, with education on how to care for the catheter and to address any gaps in understanding that may exist. The person should receive ongoing monitoring to ensure adequate dialysis, and be regularly assessed for complications. Finally, they should be educated on the importance of infection control and an appropriate medical regimen established with their cooperation.[21]

- Dialysis process

Hookup

Hookup Infusion

Infusion Diffusion (fresh)

Diffusion (fresh) Diffusion (waste)

Diffusion (waste) Drainage

Drainage

The abdomen is cleaned in preparation for surgery and a catheter is surgically inserted with one end in the abdomen and the other protruding from the skin.[22] Before each infusion the catheter must be cleaned, and flow into and out of the abdomen tested. 2-3 liters of dialysis fluid is introduced into the abdomen over the next ten to fifteen minutes.[17] The total volume is referred to as a dwell[23] while the fluid itself is referred to as dialysate. The dwell can be as much as 3 liters, and medication can also be added to the fluid immediately before infusion.[17] The dwell remains in the abdomen and waste products diffuse across the peritoneum from the underlying blood vessels. After a variable period of time depending on the treatment (usually 4–6 hours[17] ), the fluid is removed and replaced with fresh fluid. This can occur automatically while the patient is sleeping (automated peritoneal dialysis, APD), or during the day by keeping two litres of fluid in the abdomen at all times, exchanging the fluids four to six times per day (continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, CAPD).[23][24]

The fluid used typically contains sodium chloride, lactate or bicarbonate and a high percentage of glucose to ensure hyperosmolarity. The amount of dialysis that occurs depends on the volume of the dwell, the regularity of the exchange and the concentration of the fluid. APD cycles between 3 and 10 dwells per night, while CAPD involves four dwells per day of 2-3 liters per dwell, with each remaining in the abdomen for 4–8 hours. The viscera accounts for roughly four-fifths of the total surface area of the membrane, but the parietal peritoneum is the most important of the two portions for PD. Two complementary models explain dialysis across the membrane - the three-pore model (in which molecules are exchanged across membranes which sieve molecules, either proteins, electrolytes or water, based on the size of the pores) and the distributed model (which emphasizes the role of capillaries and the solution's ability to increase the number of active capillaries involved in PD). The high concentration of glucose drives the filtration of fluid by osmosis (osmotic UF) from the peritoneal capillaries to the peritoneal cavity. Glucose diffuses rather rapidly from the dialysate to the blood (capillaries). After 4-6 h of the dwell, the glucose osmotic gradient usually becomes too low to allow for further osmotic UF. Therefore, the dialysate will now be reabsorbed from the peritoneal cavity to the capillaries by means of the plasma colloid osmotic pressure, which exceeds the colloid osmotic pressure in the peritoneum by approximately 18-20 mmHg (cf. the Starling mechanism).[25] Lymphatic absorption will also to some extent contribute to the reabsorption of fluid from the peritoneal cavity to the plasma. Patients with a high water permeability (UF-coefficient) of the peritoneal membrane can have an increased reabsorption rate of fluid from the peritoneum by the end of the dwell. The ability to exchange small solutes and fluid in-between the peritoneum and the plasma can be classified as high (fast), low (slow) or intermediate. High transporters tend to diffuse substances well (easily exchanging small molecules between blood and the dialysis fluid, with somewhat improved results with frequent, short-duration dwells such as with APD), while low transporters have a higher UF (due to the slower reabsorption of glucose from the peritoneal cavity, which results in somewhat better results with long-term, high-volume dwells), though in practice either type of transporter can generally be managed through the appropriate use of either APD or CAPD.[26]

Though there are several different shapes and sizes of catheters that can be used, different insertion sites, number of cuffs in the catheter and immobilization, there is no evidence to show any advantages in terms of morbidity, mortality or number of infections, though the quality of information is not yet sufficient to allow for firm conclusions.[27]

A peritoneal equilibration test may be done to assess a person for peritoneal dialysis by determining the characteristics of the peritoneal membrane mass transport characteristics.

Improvised Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis can be improvised in conditions such as combat surgery or disaster relief using surgical catheters and dialysate made from routinely available medical solutions to provide temporary renal replacement for people with no other options.[28]

Epidemiology

As of 2017, hemodialysis is the most widely available renal replacement modality found in 96% of countries whereas peritoneal dialysis (PD) is only available in 75% of countries.[10] In 2016, the proportion of people receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) was estimated at 11% with wide differences between different countries and regions.[29] In Hong Kong and Mexico, PD is more common than the world average, with Mexico conducting most of its dialysis through PD, while Japan and Germany have rates lower than the world average.[30] Peritoneal dialysis first models, patients requiring renal replacement therapy are placed on PD first, and financial incentives for using PD are associated with increase uptake of PD in multiple countries.[29]

East and Southeast Asia

Hong Kong has the highest rate of PD use worldwide at 71.9% in 2014, while in Mainland China had 20% in 2014, 23% in Thailand during 2012, and 10-20% in Vietnam during 2011.[29] Hong Kong had a PD-first model since 1985, Thailand began a PD-first model since 2008 which increased their levels of PD from <10%.[29]

Americas

Prevalence in of PD use was 9.7% in USA during 2013 and 16.3% in Canada during 2013.[29] The lower PD rates in the USA are due to higher availability of large corporate owned hemodialysis centers. There have been recent increase in PD uptake in the USA due to changes to medicare reimbursement such as bundled payment for dialysis this incentivizes use of PD which is a less costly modality for dialysis.[29]

Overall, prevalence of PD use is 24.6% in Latin America during 2011.[29] Within Latin America, hemodialysis has a higher growth rate in use compared to PD between 1994 - 2010. In 2010, the most prevalent use of PD were in Mexico 55.9% and El Salvador 67.6%. Between 2000 - 2010, Colombia's PD rate dropped from 54% to 31.3%.[31]

History

Peritoneal dialysis was first carried out in the 1920s; however, long-term use did not come into medical practice until the 1960s.[32] The timeline was

- 1923 – Georg Ganter performs the first peritoneal dialysis in a guinea pig and attempts the procedure in humans, without success. Hypertonic saline was used as the dialysate.[32][33]

- 1946 – Howard Frank, Arnold Seligman, and Jacob Fine of Beth Israel Hospital in Boston report the first successful use of peritoneal dialysis in clinical practice,[33] in a 51-year-old man with acute renal failure caused by sulfathiazole poisoning.[34]

- 1959 – Paul Doolan and Richard Ruben of Naval Hospital Oakland first use peritoneal dialysis to treat end-stage renal disease, in a 33-year-old woman named Willie Mae Stewart. After 6 months of intermittent dialysis, she declines further treatment due to complications and dies in June 1960.[35]

- 1964–1965 – Henry Tenckhoff, G. Shilipetar and Fred Boen of the University of Washington report the first case of home peritoneal dialysis, with long-term success despite technical difficulties and a burdensome process.[35][36]

- 1968 – Henry Tenckhoff creates the Tenckhoff catheter, avoiding the need to replace the catheter in the abdomen at every treatment.[37]

Comparison to Hemodialysis

Compared to hemodialysis, PD allows greater patient mobility, produces fewer swings in symptoms due to its continuous nature, and phosphate compounds are better removed, but large amounts of albumin are removed which requires constant monitoring of nutritional status.[10] The costs of PD are generally lower than those of HD in most parts of the world, this cost advantage is most apparent in developed economies.[38] There is insufficient research to adequately compare the risks and benefits between CAPD and APD; a Cochrane Review of three small clinical trials found no difference in clinically important outcomes (i.e. morbidity or mortality) for patients with end stage renal disease, nor was there any advantage in preserving the functionality of the kidneys. The results suggested APD may have psychosocial advantages for younger patients and those who are employed or pursuing an education.[39]

PD may also be used for patients with cardiac instability as it does not result in rapid and significant alterations to body fluids, and for patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus due to the inability to control blood sugar levels through the catheter.

Society and culture

Economics

The cost of dialysis treatment is related to how wealthy the country is.[7] In the United States peritoneal dialysis costs the government about $53,400 per person per year.[4]

References

- ↑ Perl, Jeffrey; Bargman, Joanne M. (2016-11-01). "Peritoneal dialysis: from bench to bedside and bedside to bench". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 311 (5): F999–F1004. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00012.2016. ISSN 1931-857X. PMID 27009336.

- ↑ Billings DM (2008-11-01). Lippincott's Content Review for NCLEX-RN. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 575. ISBN 9781582555157. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 453. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- 1 2 3 4 Lim K, Palsson R, Siedlecki A (October 2016). "Dialysis Initiation During the Hospital Stay". Hospital Medicine Clinics. 5 (4): 467–477. doi:10.1016/j.ehmc.2016.05.008.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- 1 2 Ronco C, Crepaldi C, Cruz DN, eds. (2009). Peritoneal Dialysis: From Basic Concepts to Clinical Excellence. Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers. p. 244. ISBN 9783805592024. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13.

- 1 2 Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA (6 November 2018). "32 - Peritoneal Dialysis-Related Infections". Chronic kidney disease, dialysis, and transplantation : companion to Brenner & Rector's the kidney. ISBN 978-0-323-53172-6. OCLC 1076544294.

- ↑ Cho Y, Johnson DW (August 2014). "Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: towards improving evidence, practices, and outcomes". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 64 (2): 278–289. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.025. PMID 24751170.

- 1 2 3 4 Himmelfarb J, Vanholder R, Mehrotra R, Tonelli M (October 2020). "The current and future landscape of dialysis". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 16 (10): 573–585. doi:10.1038/s41581-020-0315-4. PMC 7391926. PMID 32733095.

- ↑ Ballinger AE, Palmer SC, Wiggins KJ, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Cross NB, Strippoli GF (April 2014). "Treatment for peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005284. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005284.pub3. PMID 24771351.

- ↑ Campbell D, Mudge DW, Craig JC, Johnson DW, Tong A, Strippoli GF (April 2017). "Antimicrobial agents for preventing peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (6): CD004679. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004679.pub3. PMC 6478113. PMID 28390069.

- ↑ Daly C, Cody JD, Khan I, Rabindranath KS, Vale L, Wallace SA (August 2014). "Double bag or Y-set versus standard transfer systems for continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in end-stage kidney disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (8): CD003078. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003078.pub2. PMC 6457793. PMID 25117423.

- ↑ Uiterwijk, Herma; Franssen, Casper F.M.; Kuipers, Johanna; Westerhuis, Ralf; Nauta, Ferdau L. (2020). "Glucose Exposure in Peritoneal Dialysis Is a Significant Factor Predicting Peritonitis". American Journal of Nephrology. S. Karger AG. 51 (3): 237–243. doi:10.1159/000506324. ISSN 0250-8095. PMC 7158228. PMID 32069459. "Other studies suggest that a high peritoneal glucose load increases the risk of peritonitis, perhaps as the effect of impaired host defenses, vascular disease, and damage to the peritoneal membrane [9, 10, 11]."

- ↑ Perl J, Nessim SJ, Bargman JM (April 2011). "The biocompatibility of neutral pH, low-GDP peritoneal dialysis solutions: benefit at bench, bedside, or both?". Kidney International. 79 (8): 814–824. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.515. PMID 21248712.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Teitelbaum, Isaac (4 November 2021). "Peritoneal Dialysis". New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (19): 1786–1795. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2100152.

- 1 2 3 4 Munden J (2007). Best practices : evidence-based nursing procedures (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-532-4.

- ↑ Kawanishi H, Moriishi M (June 2007). "Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: prevention and treatment". Peritoneal Dialysis International. 27 (Suppl 2): S289–S292. doi:10.1177/089686080702702s49. PMID 17556321. S2CID 1050358.

- ↑ Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA (6 November 2018). "33 - Noninfectious Complications of Peritoneal Dialysis". Chronic kidney disease, dialysis, and transplantation : companion to Brenner & Rector's the kidney. ISBN 978-0-323-53172-6. OCLC 1076544294.

- ↑ Ehrman JK, Gordon P, Visich PS, Keteyian SJ (2008). Clinical Exercise Physiology. Human Kinetics. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-0-7360-6565-8. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Wood M, et al. (CANNT Nursing Standards Working Group) (2008-08-01). "Nephrology Nursing Standards and Practice Recommendations" (PDF). Canadian Association of Nephrology Nurses and Technologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2010-09-08.

- ↑ Harissis HV, Katsios CS, Koliousi EL, Ikonomou MG, Siamopoulos KC, Fatouros M, Kappas AM (July 2006). "A new simplified one port laparoscopic technique of peritoneal dialysis catheter placement with intra-abdominal fixation". American Journal of Surgery. 192 (1): 125–129. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.033. PMID 16769289.

- 1 2 Crowley LV (2009). An Introduction to Human Disease: Pathology and Pathophysiology Correlations. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 507–509. ISBN 978-0-7637-6591-0. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ↑ McPhee SJ, Tierney LM, Papadakis MA (2007). Current medical diagnosis and treatment. McGraw-Hill. pp. 934–935. ISBN 978-0-07-147247-0.

- ↑ Rippe B, Venturoli D, Simonsen O, de Arteaga J (2004). "Fluid and electrolyte transport across the peritoneal membrane during CAPD according to the three-pore model". Peritoneal Dialysis International. 24 (1): 10–27. doi:10.1177/089686080402400102. PMID 15104333. S2CID 25034246.

- ↑ Daugirdas JT, Blake PG, Ing TS (2006). "Physiology of Peritoneal Dialysis". Handbook of dialysis. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 323. ISBN 9780781752534. Archived from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Htay H, Johnson DW, Craig JC, Schena FP, Strippoli GF, Tong A, Cho Y (May 2019). "Catheter type, placement and insertion techniques for preventing catheter-related infections in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (5): CD004680. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004680.pub3. PMC 6543877. PMID 31149735.

- ↑ Pina JS, Moghadam S, Cushner HM, Beilman GJ, McAlister VC (May 2010). "In-theater peritoneal dialysis for combat-related renal failure". The Journal of Trauma. 68 (5): 1253–1256. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d99089. PMID 20453775. S2CID 24251777.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Li PK, Chow KM, Van de Luijtgaarden MW, Johnson DW, Jager KJ, Mehrotra R, et al. (February 2017). "Changes in the worldwide epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 13 (2): 90–103. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2016.181. PMID 28029154. S2CID 25054210.

- ↑ Grassmann A, Gioberge S, Moeller S, Brown G (December 2005). "ESRD patients in 2004: global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 20 (12): 2587–2593. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfi159. PMID 16204281.

- ↑ Rosa-Diez G, Gonzalez-Bedat M, Pecoits-Filho R, Marinovich S, Fernandez S, Lugon J, et al. (August 2014). "Renal replacement therapy in Latin American end-stage renal disease". Clinical Kidney Journal. 7 (4): 431–436. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfu039. PMC 4208784. PMID 25349696.

- 1 2 Nolph KD (2013-03-09). "History of peritoneal dialysis". Peritoneal dialysis. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1.0 and 2.0. ISBN 9789401725606. Archived from the original on 2017-01-13.

- 1 2 Misra M, Phadke GM (2019). "Historical milestones in peritoneal dialysis". Contrib Nephrol. Contributions to Nephrology. 197: 1–8. doi:10.1159/000496301. ISBN 978-3-318-06476-6. PMID 34569508.

- ↑ Frank HA, Seligman AM, Fine J (1946). "Treatment of uremia after acute renal failure by peritoneal irrigation". J Am Med Assoc. 130 (11): 703–5. doi:10.1001/jama.1946.02870110027008a. PMID 21016282.

- 1 2 Drukker, William; Parsons, Frank M.; Maher, J.F. (2012-12-06). Replacement of Renal Function by Dialysis. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 422–423. ISBN 978-94-009-6768-7.

- ↑ Tenckhoff H, Shilipetar G, Boen ST (1965). "One year's experience with home peritoneal dialysis". Trans Am Soc Artif Intern Organs. 11: 11–7. doi:10.1097/00002480-196504000-00004. PMID 14329068.

- ↑ Mehrotra R, Devuyst O, Davies SJ, Johnson DW (November 2016). "The Current State of Peritoneal Dialysis". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 27 (11): 3238–3252. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016010112. PMC 5084899. PMID 27339663.

- ↑ Karopadi AN, Mason G, Rettore E, Ronco C (October 2013). Zoccali C (ed.). "Cost of peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis across the world". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 28 (10): 2553–2569. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1026.3780. doi:10.1093/ndt/gft214. PMID 23737482.

- ↑ Rabindranath KS, Adams J, Ali TZ, MacLeod AM, Vale L, Cody J, et al. (April 2007). Rabindranath KS (ed.). "Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis versus automated peritoneal dialysis for end-stage renal disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2 (2): CD006515. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006515. PMC 6669246. PMID 17443624. Archived from the original on 2009-10-08.