An inro (印籠, Inrō, lit. "stamp case") is a traditional Japanese case for holding small objects, suspended from the obi (sash) worn around the waist when wearing a kimono. They are often highly decorated with various materials such as lacquer and various techniques such as maki-e, and are more decorative than other Japanese lacquerware.[1][2]

Because traditional Japanese dress lacked pockets, objects were often carried by hanging them from the obi in containers known as sagemono (a hanging object attached to a sash). Most sagemono were created for specialized contents, such as tobacco, pipes, writing brush and ink, but the type known as inro is suitable for carrying small things, and was created in the Sengoku period (1467–1615) as a portable identity seal and medicine container for travel.[1][2]

In the middle of the Edo period (1603–1868), inro became popular as men's accessories, and wealthy merchants of the chōnin and samurai classes collected inro often beautifully decorated with lacquer. As the technique developed from the late Edo period to the Meiji period (1868–1912) and the artistic value of inro increased, inro were no longer used as an accessory and came to be regarded as an art object for collection.[1][2]

The term inro is a combination of the kanji for in (印), which means a seal or stamp, and the kanji for rō (籠), which means a basket.

Description

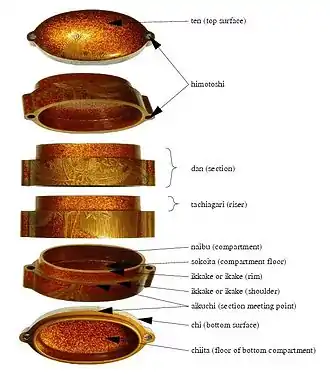

Consisting of a stack of tiny, nested boxes, inro were most commonly used to carry medicine. The stack of boxes is held together by a cord that is laced through cord runners down one side, under the bottom, and up the opposite side. The ends of the cord are secured to a netsuke, a kind of toggle that is passed between the sash and pants and then hooked over the top of the sash to suspend the inro. An ojime bead is provided on the cords between the inro and netsuke to hold the boxes together. This bead is slid down the two suspension cords to the top of the inro to hold the stack together while the inro is worn, and slid up to the netsuke when the boxes need to be unstacked to access their contents.

Inro are mostly made from paper, wood, metal, or ivory, with the most common material being paper. Paper inro are made by winding and hardening many layers of washi paper with lacquer; paper was a popular material for inro as unlike wood, it would not distort and crack over time.[1][2]

Inro are commonly decorated with lacquered designs, with the expensively produced inro featuring maki-e, raden, ivory inlay and metal foiling. Though ojime and netsuke evolved out of a mostly decorative capacity, inro retained their functionality, having evolved from strictly utilitarian articles into objects of high art and immense craftsmanship.[1][2]

For a period of time in the Edo period, inro was also used as a symbol of power. Today, among sumo referees (gyōji), only gyōji of the higher ranks are allowed to equip inro.[3]

Today, many inro are collected in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the British Museum, and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Because inro were popular among foreign collectors, there were few of the highest quality inro made from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period in Japan, but Masayuki Murata actively collected them from the 21st century, and today the Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum,[4] which he manages, houses many of the highest quality inro.[2]

Today, inro are made by a few craftsmen. The best lacquer technique from the end of the Edo period to the Meiji period, especially the inro technique, was almost lost in the westernization of Japanese lifestyle. However, in 1985 lacquer craftsman Tatsuo Kitamura (北村辰夫) set up his own studio "Unryuan" (雲龍庵) and succeeded in recreating them. His lacquer works are collected in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, and are an object of collection for the world's wealthy.[5][6][7][8] Nowadays, inro are rarely worn as kimono accessories, but there are collectors all over the world.[2]

Inro components

Inro components

Inro cabinet with a waterfall design in maki-e lacquer, Edo or Meiji period, 19th century

Inro cabinet with a waterfall design in maki-e lacquer, Edo or Meiji period, 19th century Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum

Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum

Gallery

Inro with a design of cranes standing beneath a gnarled pine tree and netsuke depicting Minamoto no Yoshitsune and Benkei, Edo period, 18th century

Inro with a design of cranes standing beneath a gnarled pine tree and netsuke depicting Minamoto no Yoshitsune and Benkei, Edo period, 18th century Inro with fox's wedding (kitsune no yomeiri). Edo period, late 18th–early 19th century

Inro with fox's wedding (kitsune no yomeiri). Edo period, late 18th–early 19th century Inro with design of blossoming plums, by Hara Yōyūsai and Sakai Hōitsu, Edo period, early 19th century

Inro with design of blossoming plums, by Hara Yōyūsai and Sakai Hōitsu, Edo period, early 19th century Inro with tanabata story of the weaver and the herdboy, by Nomura Kyūkoku, Edo period, early 19th century

Inro with tanabata story of the weaver and the herdboy, by Nomura Kyūkoku, Edo period, early 19th century Inro with peacocks and flowers, by Koma Yasutada, Edo period, 19th century

Inro with peacocks and flowers, by Koma Yasutada, Edo period, 19th century Inro with treasure boat (takarabune), by Kajikawa Bunryūsai, Edo period, 19th century

Inro with treasure boat (takarabune), by Kajikawa Bunryūsai, Edo period, 19th century Inro with design of eulalia grass and deer, with eagle netsuke, Edo period, 19th century

Inro with design of eulalia grass and deer, with eagle netsuke, Edo period, 19th century Inro with design of two hawks on tasseled perches, Edo period, 19th century

Inro with design of two hawks on tasseled perches, Edo period, 19th century Inro, design of minute patterns in mother-of-pearl inlay, Somada school, Edo period, 19th century

Inro, design of minute patterns in mother-of-pearl inlay, Somada school, Edo period, 19th century Inro by Shibata Zeshin, Meiji period, 19th century

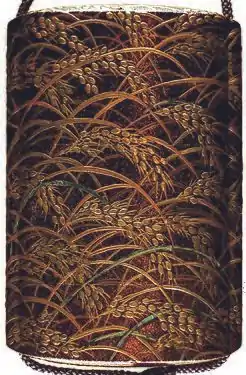

Inro by Shibata Zeshin, Meiji period, 19th century Inro with the rice ears, by Yamada Joka, 19th century

Inro with the rice ears, by Yamada Joka, 19th century Inro. Twelve calendrical animals in a landscape, 19th century

Inro. Twelve calendrical animals in a landscape, 19th century

See also

- Sporran (Scottish)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Masayuki Murata. 明治工芸入門 pp. 104–106. Me no Me, 2017 ISBN 978-4907211110

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Yūji Yamashita. 明治の細密工芸 pp. 79–81. Heibonsha, 2014 ISBN 978-4582922172

- ↑ 行司なくして大相撲は成り立たない!土俵支える裏方"行司"とは. NHK. July 5, 2019

- ↑ Kiyomizu Sannenzaka Museum

- ↑ Unryuan Kitamura Tatsuo. Lesley Kehoe Galleries

- ↑ 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa

- ↑ 超絶の伝統工芸技術の復元から 世界ブランド構築へのマーケティングヒストリー Web Dentsu. September 5, 2016

- ↑ 雲龍庵とは何者ぞ!細部に宿る漆工の美 超絶技巧の全貌 雲龍庵と希龍舎. Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun. September 21, 2017

External links

- Netsuke: masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains many examples of Iiro

- Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery