| Part of a series on |

| Native Americans in the United States |

|---|

The indigenous peoples of Florida lived in what is now known as Florida for more than 12,000 years before the time of first contact with Europeans. However, the indigenous Floridians living east of the Apalachicola River had largely died out by the early 18th century. Some Apalachees migrated to Louisiana, where their descendants now live; some were taken to Cuba and Mexico by the Spanish in the 18th century, and a few may have been absorbed into the Seminole and Miccosukee tribes.

Paleoindians

The first people arrived in Florida before the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna. Human remains and/or artifacts have been found in association with the remains of Pleistocene animals at a number of Florida locations. A carved bone depicting a mammoth found near the site of Vero man has been dated to 13,000 to 20,000 years ago.[1][2] Artifacts recovered at the Page-Ladson site date to 12,500 to 14,500 years ago.[3] Evidence that a giant tortoise was cooked in its shell at Little Salt Spring dates to between 12,000 and 13,500 years ago.[4] Human remains and artifacts have also been found in association with remains of Pleistocene animals at Devil's Den,[5] Melbourne,[6] Warm Mineral Springs,[7] and the Cutler Fossil Site.[8] A Bison antiquus skull with an embedded projectile point has been found in the Wacissa River. Other important Paleoindian sites in Florida include Harney Flats in Hillsborough County,[9] the Nalcrest site, and Silver Springs.[10]

Florida's environment at the end of the Pleistocene was very different from that of today. Because of the enormous amount of water frozen in ice sheets during the last glacial period, sea level was at least 100 metres (330 ft) lower than now. Florida had about twice the land area, its water table was much lower. Its climate also was cooler and much drier. There were few running rivers or springs in what is today's Florida. The few water sources in the interior of Florida were rain-fed lakes and water holes over relatively impervious deposits of marl, or deep sinkholes partially filled by springs.[11]

With water available only at scattered locations, animals and humans would have congregated at the water holes to drink. The concentration of animals would have attracted hunters. Many Paleoindian artifacts and animal bones showing butchering marks have been found in Florida rivers, where deep sinkholes in the river bed would have provided access to water. Sites with Paleoindian artifacts also have been found in flooded river valleys as much as 17 feet (5.2 m) under the Gulf of Mexico, and suspected sites have been identified up to 20 miles (32 km) offshore under 38 feet (12 m) of water. Half of the Paleoindian sites in Florida may now be under water in the Gulf of Mexico. Materials deposited in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene in sinkholes in the beds of rivers were covered by silt and sealed in place before the water table rose high enough to create running rivers, and those layers remained undisturbed until excavated by archaeologists. These deposits preserved organic materials, including bone, ivory, wood, and other plant remains.[12]

Archaeologists have found direct evidence that Paleoindians in Florida hunted mammoths, mastodons, Bison antiquus, and giant tortoises. The bones of other large and small animals, including ground sloths, tapirs, horses, camelids, deer, fish, turtles, shellfish, snakes, raccoons, opossums, and muskrats are associated with Paleoindian sites.[13]

Stone tools

Organic materials are not well preserved in the warm, wet climate and often acidic soils of Florida. Organic materials that can be dated through radiocarbon dating are rare at Paleoindian sites in Florida, usually found only where the material has remained under water continuously since the Paleoindian period. Stone tools are therefore often the only clues to dating prehistoric sites without ceramics in Florida.[14][15]

Projectile points (probably used on spears, the bow and arrow did not appear until much later) have distinctive forms that can be fairly reliably assigned to specific time periods. Based on stone artifacts, Bullen divided pre-Archaic Florida into four periods, Early Paleo-Indian (10000-9000 BCE), Late Paleo-Indian (9000-8000 BCE), Dalton Early (8000-7000 BCE), and Dalton Late (7000-6000 BCE).[16] Purdy defined a simpler sequence, Paleo Indian (10000-8000 BCE, equivalent to Bullen's Early and Late Paleo-Indian) and Late Paleo (8000-7000 BCE, equivalent to Bullen's Dalton Early).[17] Later discoveries have pushed the beginning of the Paleoindian period in Florida to an earlier date. The earliest well-dated material from the Paleoindian period in Florida is from the Page-Ladson site, where points resembling pre-Clovis points found at Cactus Hill have been recovered from deposits dated to 14,588 to 14,245 calibrated calendar years BP (12638-12295 BCE), about 1,500 years before the appearance of the Clovis culture.[18] Milanich places the end of the Paleoindian period at about 7500 BCE.[19] During the early Paleoindian period in Florida, before 10,000 years ago, projectile points used in Florida included Beaver Lake, Clovis, Folsom-like, Simpson, Suwannee, Tallahassee, and Santa Fe points. Simpson and Suwannee points are the most common early Paleoindian points found in Florida. In the late Paleoindian period, 9,000 to 10,000 years ago (8000-7000 BCE), Bolen, Greenbriar, Hardaway Side-Notched, Nuckolls Dalton and Marianna points were in use, with the Bolen point being the most commonly found.[16][20]

Most projectile points associated with early Paleoindians have been found in rivers. Projectile points of the late Paleoindian period, particularly Bolen points, are often found on dry land sites, as well as in rivers.[21]

Paleoindians in Florida used a large variety of stone tools besides projectile points. These tools include blades, scrapers of various kinds, spokeshaves, gravers, gouges, and bola stones. Some of the tools, such as the Hendrix scraper of the early Paleoindian period, and the Edgefield scraper of the late Paleoindian period, are distinctive enough to aid in dating deposits.[22]

Other tools

A few underwater sites in Florida have yielded Paleoindian artifacts of ivory, bone, antler, shell, and wood. A type of artifact found in rivers in northern Florida is the ivory foreshaft. One end of a foreshaft was attached to a projectile point with pitch and sinew. The other end was pointed, and pressure-fitted into a wood shaft. The foreshafts were made from mammoth ivory, or possibly, in some cases, from mastodon ivory. A shell "trigger" may be from an atlatl (spear-thrower). Other tools include an eyed needle made from bone, double pointed bone pins, part of a mortar carved from an oak log, and a non-returning boomerang or throwing stick made from oak.[23]

Archaic period

The Archaic period in Florida lasted from 7500 or 7000 BCE until about 500 BCE. Bullen divided this period into the Dalton Late, Early Pre-ceramic Archaic, Middle Pre-ceramic Archaic, Late Pre-ceramic Archaic, Orange and Florida Transitional periods. Purdy divided it into a Preceramic Archaic period and an Early Ceramic period. Milanich refers to Early (7500-5000 BCE), Middle (5000-3000 BCE) and Late (3000-500 BCE) Archaic periods in Florida.[16][17][24]

Several cultures become distinguishable in Florida in the middle to late Archaic period. In northeast Florida, the pre-ceramic Mount Taylor period (5000-2000 BCE) was followed by the ceramic Orange culture (2300-500 BCE). The Norwood culture in the Apalachee region of Florida (2300-500 BCE), was contemporary with the very similar Orange culture. The late Archaic Elliott's Point complex, found in the Florida panhandle from the delta of the Apalachicola River westward, may have been related to the Poverty Point culture.[25] The area around Tampa Bay and southwest Florida (from Charlotte Harbor to the Ten Thousand Islands) each had as yet unnamed late Archaic regional cultures using ceramics.[26]

Post-Archaic period

Pre-historic sites and cultures in the eastern United States and southeastern Canada that followed the Archaic period are generally placed in the Woodland period (1000 BCE – 1000 CE) or the later Mississippian culture period (800 or 900–1500). The Woodland period is defined by the development of technology, including the introduction of ceramics and (late in the Woodland period) the bow and arrow, the adoption of agriculture, mound-building, and increased sedentism. These characteristics developed and spread separately. Sedentism and mound building appeared along the southwest coast of Florida (cf. Horr's Island) and in the lower Mississippi River Valley (cf. Watson Brake and Poverty Point) well before the end of the Archaic period. Ceramics appeared along the coast of the southeastern United States soon after. Agriculture spread and intensified across the Woodland area throughout the Woodland and Mississippian culture periods but appeared in north central and northeastern Florida only after about 700 and had not penetrated the middle and lower Florida peninsula at the time of first contact with Europeans.[27][28][29]

Post-Archaic cultures in Florida

| Defined culture | Time range | Geographic range | |

| Belle Glade culture | 1050 BCE – Historic | Lake Okeechobee basin and Kissimmee River valley | |

| Glades culture | 550 BCE – Historic | Everglades, southeast Florida and Florida Keys | |

| Manasota culture | 550 BCE – 800 CE | central peninsular Gulf coast of Florida | |

| St. Johns culture | 550 BCE – Historic | east and central Florida | |

| Caloosahatchee culture | 500 BCE – Historic | Charlotte Harbor to Ten Thousand Islands | |

| Deptford culture – Gulf region | 500 BCE–150/250 CE | Gulf coast from Florida/Alabama border to Charlotte Harbor, southwest Georgia, southeast Alabama | |

| Deptford culture – Atlantic region | 500 BCE–700 CE | Atlantic coast from mouth of St. Johns River, Florida to Cape Fear, North Carolina | |

| Swift Creek culture | 150–350 | eastern Florida Panhandle and southern Georgia | |

| Santa Rosa-Swift Creek culture | 150–350 | western Florida Panhandle | |

| Weeden Island cultures 100–1000 CE |

Weeden Island I, including | 100–700 | Florida Panhandle, north peninsular Gulf coast in Florida, interior north Florida, and southwest Georgia |

| – Cades Pond culture | 200–750 | north-central Florida | |

| – McKeithen Weeden Island culture | 200–700 | north Florida | |

| Weeden Island II, including | 750–1000 | Florida Panhandle, north peninsular Gulf coast in Florida, and southwest Georgia | |

| – Wakulla culture | 750–1000 | Florida Panhandle | |

| Alachua culture | 700 – Historic | north central Florida | |

| Suwannee Valley culture | 750 – Historic | north Florida | |

| Safety Harbor culture | 800 – Historic | central peninsular Gulf coast of Florida | |

| Fort Walton culture – a Mississippian culture | 1000 – Historic | Florida Panhandle and southwest Georgia | |

| Pensacola culture – a Mississippian culture | 1250 – Historic | western part of Florida Panhandle, southern Alabama and southern Mississippi | |

Early modern period

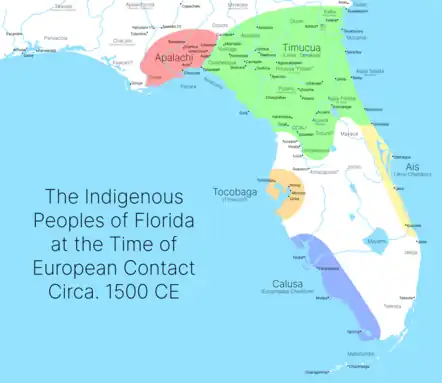

European colonists encountered numerous groups of indigenous peoples in Florida. Recorded information on various groups ranges from numerous detailed reports to the mere mention of a name. Some of the indigenous peoples were taken into the system of Spanish missions in Florida, others had sporadic contact with the Spanish without being brought into the mission system, but many of the peoples are known only from mention of their names in historical accounts. All of these peoples were essentially extinct in Florida by the end of the 18th century.

Most died from exposure to Eurasian infectious diseases, such as smallpox and measles, to which they had no immunity; others died from conflict with European colonists in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. During the initial period of Spanish colonization, groups of conquistadors came into conflict with Florida Indians, which combined with Spanish-introduced diseases devastated their population. In the 17th and 18th centuries, English colonists from the Province of Carolina and the Indian allies carried out several raids against the Spanish mission system, further devastating the indigenous population of Florida. The few survivors migrated out of Florida, mainly to Cuba and New Spain with the Spanish when they ceded Florida to Great Britain in 1763 following the Seven Years' War, although a few Apalachee reached Louisiana, where their descendants still live.

Indigenous peoples encountered by Europeans

This section includes the names of tribes, chiefdoms and towns encountered by Europeans in what is now the state of Florida and adjacent parts of Alabama and Georgia in the 16th and 17th centuries:

- Ais people – They lived along the Indian River Lagoon in the 17th century and maintained contact with the Spanish in St. Augustine.

- Alafay (Alafaes, Alafaia, Elafay, Costa, Alafaia/Alafaya/Alafeyes Costas) – Closely related to or part of Pohoy.

- Amacano – When first reported by the Spanish in the 1620s, they lived along the Big Bend coast of Florida, west from the mouth of the Suwannee River along the coast of Apalachee Bay, and spoke the same language as the Chatato, Chine and Capara/Pacara. The Amacano battled with the Pohoys of Tampa Bay in the 1620s, with the Spanish brokering a peace between the two peoples in 1628 or 1629. The Amacano requested a missionary when missions were first established in Apalachee Province in 1633. A mission may have been established among the Amacano at that time, but there is no certain record of it. Spanish records mention the Amacano in 1638, in connection with an incident in which Apalachees and Timucuas had retaliated against the Chatato and Apalachicoli, who had killed some Christians in those provinces, although Hann states it is not clear how the Amacano were involved. The Amacano do not appear in Spanish records again until 1674, when some were living, along with some Capara/Pacara, in the Chine village of Chaccabi, which was served by the mission of San Luis "on the seacoast" (Chaccabi was 10 to 11 leagues south of Apalachee). The Amacano are last mentioned by the Spanish in 1704, when the Apalachee Province was overrun and destroyed by the Province of Carolina and its native allies.[30][31][32]

- Apalachee – A major chiefdom of people who spoke Apalachee, a Muskogean language, and the western anchor of the Spanish mission system. After raids by English colonists from the Province of Carolina and their Indian allies devastated Apalachee Province the survivors scattered, sometimes seeking shelter near the Spanish settlements of St. Augustine, San Marcos, and Pensacola. Some were taken to Cuba and Mexico when the Spanish withdrew from Florida in 1763. A small group migrated to Louisiana, where their descendants live.

- Apalachicola band – The Apalachicola band was a group of towns along the Apalachicola River in Florida early in the 19th century. The towns were assigned several small reservations along the Apalachicola River in the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek but were forced to move west in the 1830s.

- Boca Ratones – Known only from records of the 1743 mission attempt on Biscayne Bay.[33]

- Bomto (Bonito) – known only from the middle of the 18th century as relations of the Mayaca and Jororo and enemies of the Pohoy.[34]

- Calusa – A major tribe centered on the Caloosahatchee River, politically dominant over other tribes in southern Florida. The Spanish maintained contact with them but did not succeed in missionary attempts.

- Caparaz – An alternate form of Pacara (see below), occurring once in Spanish records.[35]

- Chatot people (Chatato, Chacato, Chactoo) – Located in the upper Apalachicola and Chipola river basins. Related in some way to the Pensacola. The Spanish established three missions to this tribe near the upper part of the Apalachicola River.

- Chine – The Chine lived to the south of the Apalachee in the later part of the 17th century. The Chine first appeared in Spanish records with the founding of the mission of St. Peter the Apostle in the village of Chaccabi in 1674. The village of Chaccabi may have been located on the Rio Chachave, now known as Spring Creek on the coast west of St. Marks.[36] They are believed to have spoken the same language as the Amacano and Capara/Pacara.[31] The Spanish mission of San Luís "on the seacoast" served three towns that included members of the Amacano, Caparaz and Chine tribes.[32] Also said to be a branch of the Chatato.[37]

- Chisca - The Chisca lived in eastern Tennessee in the 16th century, then appeared throughout much of Spanish Florida in the 17th century. In the 18th century they became known as the Euchee or Yuchi.

- Costas – Name applied at different times to Ais, Alafaes, Keys Indians and Pojoy, and to otherwise unidentified refugees near St. Augustine.[38]

- Guacata (Vuacata) – Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda implied that the Guacata were part of the Ais and that the Guacata spoke the same language as the Ais and Jaega.[39]

- Guazoco or Guacozo – Town near the upper reaches of the Withlacoochee River passed through by the de Soto expedition. This was the farthest south that the Spanish found maize being cultivated.[40]

- Guale – Originally living along the central Georgia coast; the survivors of the raids by English colonists and their Indian allies moved from Georgia into Florida.

- Jaega – Living along the Florida Atlantic coast south of the Ais, this group was subject to, and possibly a junior branch of, the Ais.

- Jobe (Hobe) – A Jaega town.

- Jororo – A small tribe in the upper St. Johns River watershed, related to the Mayacas, and taken into the Spanish mission system late in the 17th century.

- Keys Indians – Name given by the Spanish to Indians living in the Florida Keys in the middle of the 18th century, probably consisted of Calusa and refugees from other tribes to the north.

- Luca – Town near the Withlacoochee River north of Guazoco, passed through by the de Soto expedition.[40]

- Macapiras or Amacapiras – Known only as refugees at St. Augustine in the mid-17th century, in the company of Jororo and Pojoy peoples.[41]

- Mayaca people – A small tribe in the upper St. Johns River watershed, related to the Jororos, and taken into the Spanish mission system in the 17th century.

- Mayaimi – Lived around what is now called Lake Okeechobee, very limited contact with Europeans.

- Mayajuaca – Mentioned by Fontaneda in association with the Mayaca.[42]

- Mocoso (Mocoço, Mocogo) – Chiefdom on the east side of Tampa Bay at the time of the de Soto expedition, had disappeared by the 1560s.[43]

- Muklasa – Town affiliated with either Alabama people or Koasati (possibly speaking a related language), said to have moved to Florida after the Creek War.[44]

- Muspa – Town on or near Marco Island subject to the Calusa, name later applied to people living around Charlotte Harbor.

- Pacara – First mentioned in 1675 as residing, together with the Amacano and the Chine, at the mission Assumpcíon (or Assuncíon) del Puerto or de Nuestra Señora in the town of Chaccabi near Apalachee Bay south of Apalachee Province. The Pacara probably spoke the same language, or a closely related language, as the Chatatos, Amacanos and Chines, and were probably descendants of people of the Fort Walton culture who had migrated into Apalachee Province in the early 1670s. The Pacara are mentioned a few times in Spanish records in connection with missions in Apalachee Province, the last time in 1702, when they are described as "heathens".[45]

- Pawokti – Town associated with Tawasa, the people may have relocated to Florida panhandle.[46]

- Pensacola – Lived in the Florida panhandle. May have spoken the same language as the Chatato.[31]

- Pohoy – Chiefdom on Tampa Bay in the 17th century, refugees from Uchise raids in various places in Florida in the early 18th century.

- Sabacola - A town of the Apalachicola. A dependent town, called Sabacola el Menor, was located in Florida for a few years in the 17th century, when it hosted a Spanish mission, Santa Cruz de Sabacola.

- Santa Luces – Tribe briefly mentioned in Spanish records from the middle of the 18th century. Santa Lucía was the name the Spanish gave to an Ais town where they had tried to establish a fort and mission in the 17th century.[47]

- Surruque – Tribe that lived north of the Ais, possibly related to either Ais or the Jororos and Mayacas.

- Tequesta – Lived in southeastern Florida. Spanish made two short-lived attempts to establish a mission with them.

- Timucua – Major group of peoples in northeastern Florida and southeastern Georgia speaking a common language. Many of the Timucua-speaker were brought into the mission system. Other peoples speaking Timucua are only poorly known. Known to be part of this large, loosely associated group are the following:

- Acuera – Lived around the Oklawaha River, part of the mission system.

- Agua Fresca – Lived along the middle St. Johns River, part of the mission system.

- Arapaha – May have lived in southern Georgia.

- Ibi – Lived in southern Georgia, part of the mission system.

- Itafi (or Icafui) – Lived in southeastern Georgia, part of the mission system. Survivors of the raids by English colonists and their Indian allies may have relocated to Florida.

- Mocama – Lived along the coast in northeastern Florida and southeastern Georgia, part of the mission system.

- Saturiwa – Chiefdom on the lower St. Johns River, part of the mission system,

- Tacatacuru – Chiefdom on Cumberland Island, Georgia. Survivors of the raids by English colonists and their Indian allies may have relocated to Florida.

- Northern Utina (Timucua proper) – Lived in north-central Florida, part of the mission system,

- Ocale – Lived in north-central Florida, part of the mission system.

- Oconi – Lived in southeastern Georgia.

- Onatheagua – Lived in north-central Florida, perhaps identifiable as Northern Utina

- Osochi - Swanton suggests this was a Timucuan group, connecting the name to Uzachili, chief of Yustaga when de Soto passed through that chiefdom. The Osochi are believed to have migrated northward after the Timucua Rebellion of 1656, settling along the Flint River, and associating with the Hitchiti, especially after being relocated to Arkansas and the Indian Territory.[48]

- Potano – Chiefdom in north-central Florida, part of the mission system.

- Tucururu – A subdivision of or associated with the Acuera.[49]

- Utina – Lived along the middle St. Johns River.

- Utinahica - Town on the Altamaha River in Georgia.

- Yufera – Lived in southeastern Georgia, part of the mission system. Survivors of the raids by English colonists and their Indian allies may have relocated to Florida.

- Yustaga – Lived in north-central Florida, part of the mission system.

- Tocaste – Town near Lake Tsala Apopka, passed through by the de Soto expedition.[40]

- Tocobaga – Chiefdom on Tampa Bay. Spanish made one unsuccessful attempt to establish a mission.

- Uzita – Chiefdom on the south side of Tampa Bay at the time the de Soto expedition, disappeared by the 1560s.

- Vicela – Town near the Withlacoochee River north of Luca, passed through by the de Soto expedition.[40]

- Viscaynos – Name given by the Spanish to Indians living in the vicinity of Key Biscayne (Cayo Viscainos) in the 17th century.

18th and 19th centuries

From the beginning of the 18th century, various groups of Native Americans, primarily Muscogee people (called Creeks by the English) from north of present-day Florida, moved into what is now the state. The Creek migrants included Hitchiti and Mikasuki speakers. There were also some non-Creek Yamasee and Yuchi migrants. They merged to form the new Seminole ethnicity.

Groups known to have been in Florida in the latter half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century include:

- Alachua Seminoles - Around 1750, a Hitchiti-speaking group of Oconis, led by Ahaya, moved to Florida, settling on what is now known as Paynes Prairie. They were joined by migrants from other Hitchiti-speaking Lower Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy and kept many captured Yamasees as slaves.[50][51] Ahaya's people were the first to be called "Seminole".[lower-alpha 1] The Alachua Seminoles became involved in the Patriot War of East Florida in 1812. After fending off attacks on their largest town by militia from Georgia, the Alachua Seminoles moved south to the area around Okahumpka. The chief of the Alachua Seminole during the Second Seminole War was Micanopy, likely a great-nephew of Ahaya.[54][55]

- Apalachicola band - Several groups of Mucogee-speakers who had settled along the Apalachicola River by the early 19th century were allowed to stay on small reservations along the Apalachicola River when most of the Native Americans in Florida were moved onto a reservation in the interior of the peninsula by the terms of the Treaty of Moultrie Creek. They gave up their reservations and move to the Indian Territory in the 1830s.

- Black Seminoles

- Chiscas - People from Tennessee and Virginia who migrated into Florida in the 17th century. Some became known as Yuchi, while others may have assimilated into other tribes.

- Choctaws - A band of Choctaws was reported to be living near Charlotte Harbor in 1822. An 1823 report indicated that Choctaw refugees from the First Seminole War were in Florida. Mikasukee-speaking Seminole informants told William Sturtevant in the 1950s that there had never been Choctaws in Florida.[56]

- Creeks

- Mikasukis - Early in the 18th century the Spanish in Florida tried to recruit groups from the Muscogee Confederacy to move into Florida to replace the recently devastated Apalachee and Timucua peoples as buffers against English colonists in the Province of Carolina. Tamathlis and Chiahas moved into the old Apalachee Province, eventually coalescing onto the Mikasuki. The town of Mikasuki, on the shores of Lake Miccosukee, is known from when the British controlled Florida (1766–1783). As a result of the First Seminole War, the Mikasukis first moved southeastward, towards territory recently vacated by the Alachua Seminoles, then back northwestward into what is now Madison County, Florida. At the time of the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, in 1823, the Mikasukis were one of the two most important bands of Native Americans in Florida west of the Suwannee River. In 1826 six chiefs from Florida, including representatives of the Mikasukis, were taken to Washington in order to impress them with the power of the United States. The Mikasukis retained a separate identity through the Second Seminole War. At the end of that war, in 1842, it was reported that there were 33 Mikasuki warriors left in Florida (along with Seminoles, Tallahassees and Creeks).[57]

- Muscogees

- Muspas - People living in southwestern Florida in the first half of the 19th century, at one time believed to be remnants of the Calusa.[58]

- Rancho Indians - Native American people and people of mixed native American and Spanish ancestry worked and lived at seasonal fishingranchos (fishing camps) established by Spanish/Cuban fishermen along the southwest coast of the Florida peninsula in the 18th century. They were all sent to Indian Territory during the Second Seminole War.[59]

- Spanish Indians - A name sometimes given to Indians remaining in southern Florida after Florida was transferred from Spain to Great Britain in 1763. These Indians were believed to be trading with Spanish/Cuban fishermen who frequented the southwest Florida coast. The name has also been applied more narrowly to a band led by Chakaika that lived deep in the Everglades. Chakaika's band is believed to have been responsible for the attack on a trading post on the Caloosahatchee River in 1839 that killed a number of soldiers and civilians, and the attack on Indian Key in 1840. Late in 1840 Colonel William S. Harney led a raid on Chakaika's camp, in which Chakaika and several of his followers were killed. The so-called "Spanish Indians" were probably primarily speakers of a Muskogean language (retrospectively called "Seminoles"), with possibly a few Calusa who had remained in Florida when the Spanish left Florida. They were reputed to speak Spanish and to have extensive dealings with the Spanish. Some of the "Spanish Indians" who raided Indian Key were heard speaking English and may have been escaped slaves who had joined the band.[60][61]

- Tallahassees - A band of Muscogee-speakers, called "Tallassees" or "Tallahassees", settled in the old Apalachee Province in the late 18th century. When Osceola was a boy, his mother migrated to Florida with him, settling among the Tallahassees. At the time of the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, in 1823, the Tallahassees were one of the two most important bands of Native Americans in Florida west of the Suwannee River. In 1826 six chiefs from Florida, including representatives of the Tallahassees of northern Florida and the Pease Creek Tallahassees, were taken to Washington in order to impress them with the power of the United States. The Tallahassees retained a separate identity through the Second Seminole War. At the end of that war, in 1842, it was reported that there were ten Tallahassee warriors left in Florida (along with Seminoles, Mikasukis and Creeks).[62]

- Yamasees

- Yuchis

A series of wars with the United States resulted in the death or removal to what is now Oklahoma of most of the above peoples and the merging of the remainder by ethnogenesis into the current Seminole and Miccosukee tribes of Florida.

20th and 21st century

The only federally recognized tribes in Florida are:

- Miccosukee – One of the two tribes to emerge by ethnogenesis from the migrations into Florida and wars with the United States. They were part of the Seminole nation until the mid-20th century, when they organized as an independent tribe, receiving federal recognition in 1962.

- Seminole – One of the two tribes to emerge by ethnogenesis from the migrations into Florida and wars with the United States.

The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis out of groups of Native Americans, most significantly Creek from what are now northern Muscogee.

Gallery

Thonotosassa type, Lorida, Florida

Thonotosassa type, Lorida, Florida Little Gasparilla Island beach find

Little Gasparilla Island beach find

See also

Notes

- ↑ In the 17th century the Spanish in Florida used cimaron to refer to Christianized natives who had left their mission villages to live "wild" in the woods.[52] Some of the Hitchiti- or Mikasukee-speakers who had settled in Florida identified themselves to the British as "cimallon" (Muskogean languages have no "r" sound, replacing it with "l"). The British wrote the name as "Semallone", later "Seminole". The use of "cimallon" by bands in Florida to describe themselves may have been intended to distinguish themselves from the primarily Muscogee-speakers of the Upper Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy (called the "Creek Confederacy" by the British). The term "Seminole" was first applied to Ahaya's band in Alachua. After 1763, when they took over Florida from the Spanish, the British called all natives living in Florida "Seminoles", "Creeks", or "Seminole-Creeks".[53]

References

- ↑ Viegas 2011.

- ↑ The Associated Press (June 22, 2011). "Ancient mammoth or mastodon image found on bone in Vero Beach". Gainesville Sun. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ↑ Halligan, Waters & Perrotti 2016.

- ↑ Purdy 2008, pp. 84–90.

- ↑ Purdy 2008, pp. 65–68.

- ↑ Purdy 2008, pp. 23–29.

- ↑ Cockrell 1990, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Carr 1986, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Daniel, Wisenbaker & Ballo 1986.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 43, 46, 47, 58.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 40–46.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, p. 46.

- ↑ Purdy 1981, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Bullen 1975, p. 6.

- 1 2 Purdy 1981, p. 8.

- ↑ Dunbar, James S. "The pre-Clovis occupation of Florida: The Page-Ladson and Wakulla Springs Lodge Data". Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, p. 58.

- ↑ Purdy 1981, pp. 8–9, 24.

- ↑ Purdy 1981, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Purdy 1981, pp. 12–32.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 48–53.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 63, 75, 85, 104.

- ↑ White & Estabrook 1994.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 85–104.

- ↑ "The Woodland Period (ca. 2000 B.C. - A.D. 1000)". U. S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Milanich 1994, pp. 108–09.

- ↑ Milanich 1998, p. 103.

- ↑ Hann 2006, pp. 22–24.

- 1 2 3 Milanich 1995, p. 96.

- 1 2 Geiger 1940, p. 130.

- ↑ Hann 2003, p. 36.

- ↑ Hann 2003, pp. 133–4.

- ↑ Hann 2006, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Hann 2006, pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Hann 1988, p. 402.

- ↑ Hann 2003, pp. 60–1.

- ↑ Hann 2003, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 4 Milanich 2004, p. 215.

- ↑ Hann 2003, pp. 132–3.

- ↑ Hann 2003, pp. 62, 64.

- ↑ Milanich 2004, p. 213.

- ↑ Swanton 1952, pp. 134, 160.

- ↑ Hann 2006, pp. 20–22, 27.

- ↑ Swanton 1922, pp. 130, 140.

- ↑ Milanich 1995, p. 156.

- ↑ Swanton 1922, pp. 165–167.

- ↑ Hann 1996, pp. 7, 12.

- ↑ Boyd 1951, p. 9.

- ↑ Covington 1968, pp. 347, 350.

- ↑ Hann 1992, p. 451 Note 2.

- ↑ Wright 1986, pp. 4–5, 104–105.

- ↑ Patrick 1954, pp. 184–212, 230–236.

- ↑ Mahon 1985, pp. 10, 28.

- ↑ Sturtevant 1953, p. 39, 56.

- ↑ Mahon 1985, pp. 3, 5, 28, 43, 62.

- ↑ Swanton 1952, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ Hammond 1973, pp. 357, 362–363.

- ↑ Sturtevant 1953, pp. 37–41, 43–45, 47–48, 50, 52, 54–56, 64.

- ↑ Tebeau 1968, pp. 45, 64–67.

- ↑ Mahon 1985, pp. 5, 43, 62, 318.

Bibliography

- Boyd, Mark F. (1951). "The Seminole War: Its Background and Onset". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 30 (1): 3–115. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30138833.

- Bullen, Ripley P. (1975). A Guide to the Identification of Florida Projectile Points (Revised ed.). Gainesville, Florida: Kendall Books.

- Carr, Robert S. (September 1986). "Preliminary Report on Excavation at the Cutler Fossil Site (8DA2001) in Southern Florida". The Florida Anthropologist. 39 (3 Part 2). Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- Cockrell, Wilburn A. (October 1990). Walter C. Jaap (ed.). Archaeological Research at Warm Mineral Springs, Florida (PDF). American Academy of Underwater Sciences Tenth Annual Scientific Diving Symposium. pp. 69–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Covington, James W. (1968). "Migration of the Seminoles into Florida, 1700-1820". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 46 (4): 340–357. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30147280.

- Daniel, I. Randolph Jr.; Wisenbaker, Michael; Ballo, George (March–June 1986). "The organization of a Suwannee Technology: the View from Harney Flats". The Florida Anthropologist. 39 (1–2): 24–56. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- Geiger, Maynard (1940). "Biographical Dictionary of the Franciscans in Spanish Florida and Cuba (1528–1841)". Franciscan Studies. XXI. Reprinted in Thomas, David Hurst, ed. (1991). The Missions of Spanish Florida. Garland Publishing.

- Halligan, Jessi J.; Waters, Michael R.; Perrotti, Angelina (13 May 2016). "Pre-Clovis occupation 14,550 years ago at the Page-Ladson site, Florida, and the peopling of the Americas". Science Advances. 2 (5): e1600375. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E0375H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600375. PMC 4928949. PMID 27386553.

- Hammond, E. A. (April 1973). "The Spanish Fisheries of Charlotte Harbor". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 51 (4): 355–380. JSTOR 30145870.

- Hann, John H. (1988). Apalachee: The Land between the rivers. Gainesville, Florida: University Presses of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-0854-7.

- Hann, John H. (April 1990). "Summary Guide to Spanish Florida Missions and Vistas with Churches in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". The Americas. 46 (4): 417–513. doi:10.2307/1006866. JSTOR 1006866. S2CID 147329347.

- Hann, John H. (1992). "Heathen Acuera, Murder, and a Potano Cimarrona: The St. Johns River and the Alachua Prairie in the 1670s". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 70 (4): 451–474. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30148124.

- Hann, John H. (1996). A History of Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513–1763. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.

- Hann, John H. (2006). The Native American World Beyond Apalachee. University Press of Florida. ISBN 9-780-8130-2982-5.

- Mahon, John K. (1985) [1967]. History of the Second Seminole War: 1835–1942 (Second ed.). Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-1097-7.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1994). Archaeology of Precolumbian Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1273-5.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1995). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1998). Florida's Indians from Ancient Times to the Present. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1598-9.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (2004). "Early Groups of Central and South Florida". In Fogelson, R. D. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians: Southeast. Vol. 14. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 213–8. ISBN 978-0160723001.

- Patrick, Rembert W. (1954). Florida Fiasco. University of Georgia Press. LCCN 53-13265.

- Purdy, Barbara A. (1981). Florida's Prehistoric Stone Technology. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. ISBN 978-0-8130-0697-0.

- Purdy, Barbara A. (2008). Florida's People During the Last Ice Age. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-3204-7.

- Sturtevant, William C. (1953). "Chakaika and the "Spanish Indians"" (PDF). Tequesta. 13: 63–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2021-12-12 – via Digital Collections Florida International University.

- Swanton, John Reed (1922). Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Swanton, John Reed (1952). The Indian tribes of North America. Washington,D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Tebeau, Charlton W. (1968) [1964]. Man in the Everglades (Second, revised ed.). Coral Gables, Florida: University of Miami Press. LCCN 68-177768.

- Viegas, Jennifer (June 22, 2011). "Earliest Mammoth Art: Mammoth on Mammoth". Discover News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- White, Nancy Marie; Estabrook, Richard W. (March 1994). "Sam's Cutoff Shell Mound and the Late Archaic Elliott's Point Complex in the Apalachicola Delta, Northwest Florida". The Florida Anthropologist. 47 (1). Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- Wright, J. Leitch Jr. (1986). Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People (Paperback (1990) ed.). Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-9728-9.