| Act of Independence of Central America | |

|---|---|

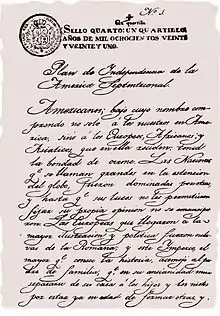

A scan of the act of independence | |

Signers of the Act of Independence | |

| Ratified | 15 September 1821 |

| Location | Legislative Assembly of El Salvador |

| Author(s) | José Cecilio del Valle |

| Signatories | 13 representatives of the provinces of the Captaincy General of Guatemala |

| Purpose | To announce separation from the Spanish Empire and provide for the establishment of a new Central American state |

The Act of Independence of Central America (Spanish: Acta de Independencia Centroamericana), also known as the Act of Independence of Guatemala, is the legal document by which the Provincial Council of the Province of Guatemala proclaimed the independence of Central America from the Spanish Empire and invited the other provinces of the Captaincy General of Guatemala[lower-alpha 1] to send envoys to a congress to decide the form of the region's independence. It was enacted on 15 September 1821.[1]

Independence movements

By the turn of the nineteenth-century, it became clear that several unique regional identities had formed in Central America, although the authority for self-governance that each of these regions held was less discernible. Eventually though, the divisions would result in the dominance of Guatemala City and the wider area of Guatemala, which held the seat of the captaincy general, the only university in Central America, and most importantly, a large population of Peninsulares. The other regions, Comayagua (modern Honduras), Nicaragua, San Salvador (modern El Salvador), and Costa Rica, were less prosperous than Guatemala, but each held varying degrees of loyalty to the Spanish crown. The combination of the American and French Revolutions, the control of Peninsular Spaniards over Central America, and Spain's role in the Peninsular War would set the stage for independence movements.[2]

The events of the Peninsular War—in particular the removal of Ferdinand VII from the Spanish throne—inspired and facilitated a series of revolts in El Salvador and Nicaragua, aimed at winning greater political autonomy for Central America. Though quickly suppressed, these uprisings formed part of the general political upheaval in the Spanish world that led to the Spanish Constitution of 1812. Between 1810 and 1814 the Captaincy General of Guatemala elected seven representatives to the new Cortes of Cádiz and formed locally elected provincial governing councils.[3]

However, shortly after his restoration to power in 1814, Ferdinand repudiated the 1812 constitution, dissolved the Cortes, and suppressed liberalism in peninsular Spain,[4] which provoked renewed unrest in the Spanish Americas. The brief restoration of the constitution during the Liberal Triennium beginning in 1820 allowed the Central American provinces to reestablish their elected councils, which then became focal points for constitutionalist and separatist sentiments. In 1821 the provincial council of Guatemala began to openly discuss a declaration of independence from Spain.[5]

Promulgation of the Act

In September the discussion turned toward an outright declaration of independence from Spain, and a document announcing the act was drawn up and debated. The 15 September council meeting at which independence was finally declared was chaired by Gabino Gaínza,[6] and the text of the Act itself was written by Honduran intellectual and politician José Cecilio del Valle[7] and signed by representatives of the various Central American provinces, including José Matías Delgado, José Lorenzo de Romaña and José Domingo Diéguez.[1] The meeting was held at the National Palace in Guatemala City, the site of which is now Centennial Park.[8]

The Province of San Salvador accepted the decision of the Guatemalan Council on 21 September,[9] and the Act was seconded by the provincial councils of Comayagua on 28 September and of Nicaragua and Costa Rica on 11 October. However, the other provinces were reluctant to accept the primacy of Guatemala in a new Central American state, and the form of the new polity that would succeed the Captaincy General was not at all clear.[10]

The increasing lack of political cohesion in Central America took new forms after the independence acts were accepted. Divisions within the urban centers of San Salvador, Comayagua, and Nicaragua, split those regions in half. In Costa Rica, its isolation from the rest of Central America combined with its previous loyalty to Spain and the rivalry between San José and Cartago to alienate it from the government in Guatemala. As Central America faced disintegration, two solutions presented themselves. The success of neighboring Mexico in its own war of independence led some in Central America to see it as the region's best chance of continued unity, while others wished for absolute independence for their own gain, for idealistic reasons, or because they feared Mexico could not protect their economic interests.[2]

Aftermath and union with Mexico

Article 2 of the Act of Independence provided for the formation of a congress to "decide the point of absolute general independence and fix, in case of agreement, the form of government and the fundamental law of governance" for the new state.[1] This constituent assembly was meant to meet the following March, but the opportunity never came. Instead, on 29 October 1821 the president of the provisional governing council of newly independent Mexico, Agustín de Iturbide, sent a letter to Gabino Gaínza (now the president of the interim government of Central America) and the council of delegates representing the provinces of Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica with a proposal that Central America join the Mexican Empire under the terms of the Three Guarantees of the Treaty of Córdoba.[11]

These guarantees, otherwise known as the Plan of Iguala, promised the continuation of the Catholic faith in the region, final independence from Spain, and the creation of a constitutional monarchy. However, most importantly for Central America, the plan called for unity among the various regional entities of northern Spanish America under one kingdom. This division had already been proposed, first by Charles II of Spain and then in the Cortes of 1820. It was intended that the Spanish colonies would be split into two kingdoms, with one encompassing the territories north of modern-day Panama and the other encompassing New Granada and the lands south of it. While the proposed division did not occur as planned, the plan did establish a legal precedent for the idea of political unity between Mexico, Guatemala, and the "Provincias Internas" and helped set the stage for the unification with Mexico.[5]

The various provincial and municipal governments of Guatemala were consulted and votes taken, with the five provinces excepting El Salvador voting in favor and with El Salvador opposing.[9][11][12] On 5 January 1822,[1] Gaínza sent a letter to Iturbide accepting Central America's annexation, and all the territories of Central America were incorporated into the Mexican Empire. They would remain united with Mexico for less than two years before seceding to form the Federal Republic of Central America as the Mexican Empire fell.[13]

Text of the Act

The Act consists of an introduction, eighteen articles, and a collection of thirteen signatures.[1]

Introduction

The introduction asserts that, after consultation with the municipal councils of other cities in the Captaincy General, the provincial council of Guatemala has agreed that there is a general public desire for independence from Spain. In response to this desire, the council has gathered together in the halls of the National Palace together with other public figures to seriously weigh the matter. Hearing the calls for independence from the streets outside the Palace, the council and the individuals gathered have determined the following articles:

Article 1

The general will of the people of Guatemala is for independence from the Spanish government and the formation of a congress, which is hereby proclaimed to the same Guatemalan people.

Article 2

Messages will be dispatched to the provinces so that they may elect deputies or representatives to come to the capital, where they will constitute a congress that will determine the form of the new state's independent government and the fundamental law by which it will be governed.

Article 3

To facilitate the appointment of deputies to the congress, they are to be chosen by the same electoral bodies that previously appointed deputies to the Spanish Cortes.

Article 4

Deputies to the Congress are to be allocated in proportion to the provinces' populations, with one deputy for every fifteen thousand citizens, including as citizens those residents of African origin.

Article 5

The provincial electoral bodies are to determine the proper number of deputies for their provinces on the basis of the latest census.

Article 6

The deputies thus elected should gather in Guatemala City to form a congress on 1 March 1822 (the following year).

Article 7

Until the meeting of the congress, the existing authorities should continue to enforce the laws under the Spanish Constitution of 1812.

Article 8

Until the meeting of the congress, the Lord Political Chief Gabino Gaínza will continue to lead the political and military government, together with a provisional advisory council.

Article 9

The advisory council will consult with the Lord Political Chief in all matters of economics and government.

Article 10

The Catholic Church will continue to be the state religion of Guatemala, with the personal safety and property of its ministers guaranteed.

Article 11

Messages will be dispatched to the leaders of religious communities to enjoin their cooperation in urging the public to preserve peace and concord during the political transition.

Article 12

The municipal council of Guatemala City will take active steps to ensure order and tranquility in the capital region.

Article 13

The Lord Political Chief will publish a manifesto announcing the decisions of the ruling council and requesting an oath of loyalty from the people to the new American government that is being established.

Article 14

The same oath will recognize the leaders of the new government in their respective roles and authorities.

Article 15

The Lord Political Chief, together with the municipal council, will solemnly mark the day upon which the people will proclaim their independence and loyalty to the new state.

Article 16

The municipal council has authorized the minting of a medal to commemorate 15 September 1821, on which they declared their independence.

Article 17

Being printed, this Act will be circulated among the various provincial councils, deputies and authorities for the harmonization of their sentiments with those of the people and this council.

Article 18

On a day to be chosen by the Lord Political Chief, there will be a solemn Mass of Thanksgiving to be followed by three days of celebrations.

Signatures

- Gabino Gaínza

- José Matías Delgado

- Manuel Antonio de Molina

- Mariano de Larrave

- Mariano de Aycinena y Piñol

- Mariano Beltranena y Llano

- José Antonio de Larrave

- Pedro de Arroyave

- José Mariano Calderón

- Antonio Rivera Cabezas

- Ysidoro de Valle y Castriciones

- José Domingo Diéguez (Secretary)

- Lorenzo de Romaña (Secretary)

See also

Notes

- ↑ As part of the adoption of the Spanish Constitution of 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz consolidated the seven historic provinces of the Captaincy General of Guatemala into only two: the Province of Guatemala (consisting of the former provinces of Guatemala, Belize, Chiapas, Honduras and El Salvador) and the Province of Nicaragua y Costa Rica. These newly combined provinces officially existed from 1812 to 1814 and from 1820 until their independence. In the Act of Independence of Central America and contemporary correspondence, Central American writers generally continued to refer to the seven historic divisions of the region as "provinces," despite the recent administrative reorganization.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Documentos de la Union Centroamericana" (PDF). Organization of American States – Foreign Trade Information System (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- 1 2 Stanger, Francis Merriman (1932). "National Origins in Central America". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 12 (1): 18–45. doi:10.2307/2506428. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2506428.

- ↑ Rieu-Millan, Marie Laure (1990). Los diputados americanos en las Cortes de Cádiz: Igualdad o independencia (in Spanish). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 978-84-00-07091-5.

- ↑ Alfonso Bullon de Mendoza y Gomez de Valugera (1991). Javier Parades Alonso (ed.). Revolución y contrarrevolución en España y América (1808–1840) (in Spanish). ACTAS. pp. 81–82. ISBN 84-87863-03-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Rojas, Xiomara Avendaño (26 February 2018). "Hispanic Constitutionalism and the Independence Process in the Kingdom of Guatemala, 1808–1823". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.599. ISBN 9780199366439. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ↑ Rodolfo Pérez Pimentel. "Gabino De Gaínza y Fernández- Medrano". Diccionario Biografico Ecuador (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Rosa, Ramón (1882). Biografía de Don José Cecilio del Valle (in Spanish). Tegucigalpa: Tipografía Nacional. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Newton, Paula (2011). Viva Travel Guides Guatemala. Viva Publishing Network. p. 158. ISBN 978-0982558546.

- 1 2 "Independencia Nacional de El Salvador". elsalvador.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Kenyon, Gordon (1961). "Mexican Influence in Central America, 1821–1823". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 41 (2): 175–205. doi:10.2307/2510200. ISSN 0018-2168. JSTOR 2510200.

- 1 2 Quirarte, Martín (1978). Visión Panorámica de la Historia de México (in Spanish) (11th ed.). Mexico: Librería Porrúa Hnos.

- ↑ "Las Provincias de Centro América se unen al Imperio Mexicano". Memoria Política de México (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Sandoval, Victor Hugo. "Federal Republic of Central America". Monedas de Guatemala. Retrieved 14 October 2014.