| 1904 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 10, 1904 |

| Last system dissipated | November 4, 1904 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Two |

| • Maximum winds | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 985 mbar (hPa; 29.09 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 6 |

| Total storms | 6 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 112-275 |

| Total damage | $2.5 million (1904 USD) |

| Related articles | |

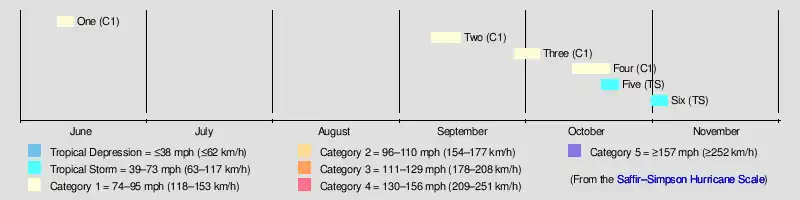

The 1904 Atlantic hurricane season featured no tropical cyclones during the months of July and August. The season's first cyclone was initially observed in the southwestern Caribbean on June 10. After this storm dissipated on June 14, the next was not detected until September 8. The sixth and final system transitioned into an extratropical cyclone offshore South Carolina on November 4. Two of the six tropical cyclones existed simultaneously.

Of the season's six tropical storms, four strengthened into a hurricane. None of these deepened further into a major hurricane, which is a tropical cyclone that reaches at least Category 3 on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project also indicated but could not confirm the presence of four additional tropical depressions throughout the season. However, the reanalysis added a previously undetected hurricane in late September and early October to the Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT).[1] The first and second systems left the most significant impacts during this season. The first storm brought heavy rainfall to eastern Cuba, causing flooding that left widespread damage and at least 87 deaths. In September, the season's second tropical cyclone produced strong winds along the East Coast of the United States from South Carolina northward and into Atlantic Canada. There were at least 18 deaths and $2.5 million (1904 USD) in damage.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 30, the third lowest value at the time and the lowest since 1864. ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have high values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[2]

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 10 – June 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); <1003 mbar (hPa) |

The first storm of the season was observed by ships over the southwestern Caribbean on June 10,[3] about 65 miles (105 km) east-southeast of Isla de Providencia. Moving north to north-northeast, the depression strengthened slowly, reaching tropical storm intensity by early on June 12. After curving to the northeast, the storm strengthened further. It became a Category 1 hurricane on the modern day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale on June 13, several hours before peaking with winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,003 mbar (29.6 inHg),[1][4] both estimated by Ramón Pérez of the Cuban Institute of Meteorology in 2000.[1] Shortly thereafter, the hurricane made landfall near Pilón in Granma Province, Cuba. Early on June 14, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm. It soon emerged into the Atlantic Ocean, but continued weakening, falling to tropical depression intensity and dissipating over the southeastern Bahamas late on June 14.[4]

In Jamaica, the slow-moving storm brought over 10 inches (250 mm) of rainfall to the western portions of the island. Subsequent flooding inundated a number of roads and washed away several bridges, isolating some areas.[5] Heavy precipitation also fell in eastern Cuba, with the city of Santiago de Cuba observing about 14 in (360 mm) of rainfall in only five hours. About 150 homes were damaged or destroyed, while many mines and roads and railways were impacted. El Cobre was also among the cities most devastated by the storm. Low-lying areas of the city were completely destroyed, as were bridges, railroad bridges, and railways.[6] At least 87 deaths occurred,[7] with some sources estimating that over 250 people were killed.[8]

Hurricane Two

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 8 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

After a three-month lull, the next tropical storm was first observed about 420 mi (680 km) northeast of Barbados on September 8.[3][4] The storm moved northwestward for several days and slowly strengthened. By 12:00 UTC on September 12, the system became a hurricane. Six hours later, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). The hurricane made landfall on Cedar Island, South Carolina, at the same intensity around 13:00 UTC on September 14.[4] A barometric pressure of 985 mbar (29.1 inHg) was observed at landfall, the lowest in relation to the system.[9] About five hours later, the cyclone weakened to a tropical storm and curved sharply northeastward. Weakening and losing tropical characteristics, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over the Delaware Bay early on September 15. The remnants briefly restrengthened into a powerful extratropical cyclone, equivalent to a Category 1 hurricane, before dissipating over Nova Scotia later that day.[4]

In South Carolina, three fishing boats sank offshore Charleston, drowning several people, while another ship capsized, causing three deaths.[10] Two additional drownings occurred in North Carolina offshore Wrightsville Beach.[11] A tornado spawned by the storm destroyed about 20 homes and damaged several other structures, including a few ginneries at a cost of $25,000, and downed telephone and electrical poles between Mount Olive and Faison, as well as causing a fatal injury.[12][13] Two other tornadoes in the state caused similar damage.[14][15] Some areas of the Carolinas experienced heavy rainfall, with 8.9 in (230 mm) in Smiths Mills, South Carolina.[16] In Maryland, strong winds caused extensive damage to trees, power lines, and crops. A death from electrocution occurred in Baltimore. Numerous vessels in the Chesapeake Bay were damaged, beached, or capsized.[17]

Nine deaths occurred in Delaware, eight after a tugboat sank and another after a schooner ran aground.[18][19] In Lewes, strong winds deroofed homes and businesses, while telegraph and telephone lines and trees were downed.[19] Heavy rainfall in Philadelphia and New York City inundated many streets and basements.[20][21][22] Winds up to 80 mph (130 km/h) in New York City shattered hundreds of windows and downed numerous trees and wires. One man died after being struck by a cast iron fire escape.[22] At New York Harbor, 19 barges broke loose from their moorings and several smaller ships were washed ashore during the storm,[18] while 15 vessels suffered damage or were grounded at Boston. Throughout southern New England, strong winds resulted in widespread damage to trees and power lines.[23] Damage in the United States reached at least $2 million.[3] In Atlantic Canada, powerful winds disrupted telephone and telegraph services.[24] A woman was killed in Halifax, Nova Scotia, when a tree fell on her.[25] The winds aided firefighters battling a large blaze in Halifax, which ultimately caused about $500,000 in damage.[26] Several incidents involving ships being sunk, run aground, or forced to return to port occurred throughout Atlantic Canada, including in New Brunswick,[27] Newfoundland,[28] and Nova Scotia.[27]

Hurricane Three

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 28 – October 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

Based on observations and continuity,[1] it is estimated that a tropical depression developed in the southwestern Caribbean Sea about 120 mi (195 km) east-southeast of Isla de Providencia at 00:00 UTC on September 28. Moving slowly northwestward, the depression intensified into a tropical storm about 24 hours later.[4] Early on October 1, based on observations from the steamship Ellis, the cyclone strengthened into a hurricane.[1] Shortly thereafter, the storm began curving west-northward and peaked with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). However, it soon began to weakened and fell to tropical storm early on October 2. Around 06:00 UTC on the following day, the system made landfall near the Belize–Mexico border with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[4] Observations from Mexico suggest that the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression around 00:00 UTC on October 4 and dissipated over Chiapas about 18 hours later.[1][4]

Hurricane Four

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 12 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 989 mbar (hPa) |

The next storm was first observed by ships early on October 12, while located about 185 mi (300 km) south-southeast of Morant Point, Jamaica.[4][3] After initially moving westward, the storm gradually curved northward over the next few days. It strengthened slowly, becoming a hurricane around 12:00 UTC on October 15.[4] Early on the following day, the cyclone made landfall in Cuba near Trinidad, Sancti Spíritus, with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). The system weakened to a tropical storm while crossing the island, before emerging into the Atlantic Ocean near the Straits of Florida late on October 16. However, early on October 17, the storm re-intensified into a hurricane.[4] At 05:00 UTC, the hurricane attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 989 mbar (29.2 inHg), which was observed by a weather station in Miami.[3]

Around 08:00 UTC on October 17, the cyclone struck Key Largo, Florida, while still at peak intensity. It weakened to a tropical storm four hours later. The storm then drifted slowly northwestward across South Florida and began executing a cyclonic loop. Late on October 18, the system emerged into the Gulf of Mexico near Boca Grande as a minimal tropical storm. The storm moved southwestward, southeastward, and then east-northeastward. It failed to re-intensify over the Gulf of Mexico and made landfall in mainland Monroe County at 10:00 UTC on October 20 with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). Around 18:00 UTC, the cyclone emerged into the Atlantic near Miami Beach and weakened to a tropical depression. Continuing east-northeastward, the storm crossed the northern Bahamas, striking Grand Bahama and the Abaco Islands. By 18:00 UTC, the cyclone dissipated about 90 mi (140 km) northeast of the Abaco Islands.[4]

In Cuba, the storm dropped heavy rainfall, leaving "significant damage" due to flooding.[3] Much of the impact in Florida was concentrated in the Miami area. Several homes were unroofed in the northern sections of the city and in "Colored Town", an African American neighborhood today known as Overtown. A few local hotels were structurally impacted, while many businesses were damaged. Winds also defoliated shrubbery and downed trees and signs. Trees and electrical poles were downed as far north as Fort Lauderdale, leaving some power outages.[29] Some citrus and pineapple crops were damaged throughout South Florida, while low-lying vegetables were ruined considerably due to flooding.[30] Offshore Florida, three sailing vessels were wrecked in the storm – the British Melrose, the German Zion, and the American James Judge. The crews of Zion and James Judge reached shore safely, but the Melrose sank offshore in heavy seas with the loss of seven crewmen. The survivors were left clinging to wreckage for nearly four days before being rescued.[3]

Tropical Storm Five

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 19 – October 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

Data from ships on October 19 indicated the presence of a tropical storm about 1,195 mi (1,925 km) northeast of Barbuda.[4][3] After initially moving southwestward, the storm briefly curved west-northwestward on October 20, shortly before turning northward. Around 12:00 UTC on October 21, the cyclone obtained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg), the latter of which was observed by a ship.[4][3] The system then curved northwestward and began accelerating. By 00:00 UTC, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone while located about 365 mi (585 km) south-southeast of Sable Island. The extratropical remnants continued rapidly north-northeastward until dissipating south of Greenland on October 23.[4]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 31 – November 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); <1005 mbar (hPa) |

The final storm of the season was detected over the Bay of Campeche based on observations from Mérida, Yucatán, on October 31.[3] The station recorded a barometric pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg), the lowest known in relation to the system while it was a tropical cyclone.[1] Initially moving northwestward, the storm curved northeastward early on November 1. It intensified slightly throughout the day, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) around 00:00 UTC the next day. Thereafter, the cyclone began weakening while approaching the Florida Panhandle. Around 12:00 UTC on November 3, the storm made landfall near Fort Walton Beach, Florida, with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h). It tracked across the Florida Panhandle, southern Georgia, and coastal South Carolina before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone just offshore South Carolina. The extratropical remnants continued rapidly northeast until dissipated near Newfoundland late on November 6.[4] Winds up to 36 mph (58 km/h) were observed in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Pensacola, Florida.[3] The storm produced light to moderate rainfall across the Southeastern United States.[16]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that have formed in the 1904 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s)–denoted by bold location names – damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1904 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | June 10–14 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 1003 | Jamaica, Cuba, Bahamas | Unknown | 87-250 | [7][8] | ||

| Two | September 8–15 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 985 | East Coast of the United States (South Carolina), Atlantic Canada | 2.4 | 18 | [3][10][11][12][17][22][25][26] | ||

| Three | September 28–October 4 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | Unknown | Central America, Mexico | Unknown | None | |||

| Four | October 12–21 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 989 | Jamaica, Cuba, Florida, Bahamas | Unknown | 7 | [3] | ||

| Five | October 19–23 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Six | October 31–November 4 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1005 | Southeastern United States (Florida) | Minor | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 6 systems | June 10 – November 4 | 80 (130) | 985 | 2.5 | 112-275 | |||||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Landsea, Christopher W.; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ↑ Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 2021. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Jose F. Partagas (1997). Year 1904 (PDF). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Hall, Maxwell (June 15, 1904). Cyclonic Depression and Flooding in Jamaica (PDF). Weather Bureau (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. p. 273. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Storm Killed Over 100" (PDF). The New York Times. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. June 18, 1904. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Rappaport, Edward N.; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose (April 22, 1997). The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492-1996 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 26, 2022.

- 1 2 "Cuba Swept by a Great Storm". Wilkes-Barre Record. Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. June 17, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved December 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Chronological List of All Hurricanes: 1851 – 2015. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- 1 2 "Lost In Gale". The Charlotte News. Charlotte, North Carolina. Associated Press. September 14, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Two Fishermen Drowned". The Wilmington Morning Star. Tarboro, North Carolina (published September 15, 1904). September 14, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Storm Disasters". The Wilmington Morning Star. Wilmington, North Carolina. September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Carolina Beneath The Rush Of A Tempest". News and Observer. Goldsboro, North Carolina (published September 15, 1904). September 13, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Clouds Met At Durham". News and Observer. Durham, North Carolina (published September 15, 1904). September 14, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Ruin Marks Three Miles". News and Observer. Warrenton, North Carolina (published September 15, 1904). September 14, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 R. W. Schoner and S. Molansky. Rainfall Associated With Hurricanes (And Other Tropical Disturbances) (PDF) (Report). United States Weather Bureau's National Hurricane Research Project. p. 222. Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- 1 2 "Havoc At Baltimore". The Salt Lake Herald. Baltimore, Maryland (published September 16, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Atlantic Coast Swept By Gale". The Salt Lake Herald. New York (published September 16, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Ashore At Breakwater". The Evening Journal. Lewes, Delaware. September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Unprecedented Rainfall". The Salt Lake Herald. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (published September 16, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Philadelphia Deluged". The Fort Wayne Sentinel. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "East Is Swept By Damaging Storm". The Fort Wayne Sentinel. New York. September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Gale At Boston". The Salt Lake Herald. Boston, Massachusetts (published September 16, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved May 26, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Worst Storm In Thirty Years". The Evening Telegram. North Sydney, Nova Scotia (published September 21, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 3.

- 1 2 "Halifax Saved By Wind's Shift". The Scranton Truth. Halifax, Nova Scotia (published September 17, 1904). September 16, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Shift Of Wind Saved The Town". The Salt Lake Herald. Halifax, Nova Scotia (published September 16, 1904). September 15, 1904. p. 1. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 1904-2 (Report). Environment Canada. November 24, 2011. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Hurricane Damages Boats". The Inter Ocean. St. John's, Newfoundland (published September 17, 1904). September 18, 1904. p. 3. Retrieved June 27, 2016 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Lower East Coast Swept by Heavy Storm". The Miami Metropolis. October 21, 1904. p. 2. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ James Berry (October 1904). Climate and Crop Service (PDF). Monthly Weather Review (Report). p. 447. Retrieved June 28, 2016.