| Old Hungarian 𐲥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗-𐲘𐳀𐳎𐳀𐳢 𐲢𐳛𐳮𐳁𐳤 Székely-magyar rovás | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | Attested from 10th century. Marginal use into the 17th century, revived in the 20th. |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Hungarian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hung (176), Old Hungarian (Hungarian Runic) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Old Hungarian |

| U+10C80–U+10CFF | |

The Old Hungarian script or Hungarian runes (Hungarian: Székely-magyar rovás, 'székely-magyar runiform', or rovásírás) is an alphabetic writing system used for writing the Hungarian language. Modern Hungarian is written using the Latin-based Hungarian alphabet. The term "old" refers to the historical priority of the script compared with the Latin-based one.[1] The Old Hungarian script is a child system of the Old Turkic alphabet.

The Hungarians settled the Carpathian Basin in 895. After the establishment of the Christian Hungarian kingdom, the old writing system was partly forced out of use during the rule of King Stephen, and the Latin alphabet was adopted. However, among some professions (e.g. shepherds who used a "rovás-stick" to officially track the number of animals) and in Transylvania, the script has remained in use by the Székely Magyars, giving its Hungarian name (székely) rovásírás. The writing could also be found in churches, such as that in the commune of Atid.

Its English name in the ISO 15924 standard is Old Hungarian (Hungarian Runic).[2][3]

Name

In modern Hungarian, the script is known formally as Székely rovásírás ('Szekler script').[4] The writing system is generally known as rovásírás, székely rovásírás,[4] and székely-magyar írás (or simply rovás 'notch, score').[5]

History

Origins

Scientists cannot give an exact date or origin for the script.

Linguist András Róna-Tas derives Old Hungarian from the Old Turkic script,[6] itself recorded in inscriptions dating from c. AD 720. The origins of the Turkic scripts are uncertain. The scripts may be derived from Asian scripts such as the Pahlavi and Sogdian alphabets, or possibly from Kharosthi, all of which are in turn derived from the Aramaic script.[7] Alternatively, according to some opinions, ancient Turkic runes descend from primaeval Turkic graphic logograms.[8]

Speakers of Proto-Hungarian would have come into contact with Turkic peoples during the 7th or 8th century, in the context of the Turkic expansion, as is also evidenced by numerous Turkic loanwords in Proto-Hungarian.

All the letters but one for sounds which were shared by Turkic and Ancient Hungarian can be related to their Old Turkic counterparts. Most of the missing characters were derived by script internal extensions, rather than borrowings, but a small number of characters seem to derive from Greek, such as ![]() 'eF'.[9]

'eF'.[9]

The modern Hungarian term for this script (coined in the 19th century), rovás, derives from the verb róni ('to score') which is derived from old Uralic, general Hungarian terminology describing the technique of writing (írni 'to write', betű 'letter', bicska 'knife, also: for carving letters') derive from Turkic,[10] which further supports transmission via Turkic alphabets.

Medieval Hungary

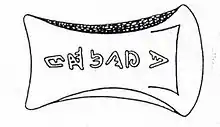

Epigraphic evidence for the use of the Old Hungarian script in medieval Hungary dates to the 10th century, for example, from Homokmégy.[11] The latter inscription was found on a fragment of a quiver made of bone. Although there have been several attempts to interpret it, the meaning of it is still unclear.

In 1000, with the coronation of Stephen I of Hungary, Hungary (previously an alliance of mostly nomadic tribes) became a kingdom. The Latin alphabet was adopted as official script; however, Old Hungarian continued to be used in the vernacular.

The runic script was first mentioned in the 13th century Chronicle of Simon of Kéza,[12] where he stated that the Székelys may use the script of the Blaks.[13][14][15] Johannes Thuróczy wrote in the Chronica Hungarorum that the Székelys did not forget the Scythian letters and these are engraved on sticks by carving.[16]

There were still three thousand Huns who fled the battle of Crimhild, who fearing from the western nations, they remained on the cliff field until the time of Árpád, and they did not call themselves Huns, but Szekelys. These Szekelys were the remains of the Huns, who when they learned that the Hungarians had returned to Pannonia for the second time, went to the returnees on the border of Ruthenia and conquered Pannonia together, but not on the Pannonian plane, they were granted estates in the mountainous borderlands together with the Blackis, where mingling with the Blackis it is said they used their letters.

It is said that in addition to the Huns who escorted Csaba, from the same nation, three thousand more people retreating, cut themselves out of the said battle, remained in Pannonia, and first established themself in a camp called Csigla's Field. They were afraid of the Western nations which they harassed in Attila's life, and they marched to Transylvania, the frontier of the Pannonian landscape, and they did not call themselves Huns or Hungarians, but Siculus, in their own word Székelys, so that they would not know that they are the remnants of the Huns or Hungarians. In our time, no one doubts, that the Székelys are the remnants of the Huns who first came to Pannonia, and because their people do not seem to have been mixed with foreign blood since then, they are also more strict in their morals, they also differ from other Hungarians in the division of lands. They have not yet forgotten the Scythian letters, and these are not inked on paper, but engraved on sticks skillfully, in the way of the carving. They later grew into not insignificant people, and when the Hungarians came to Pannonia again from Scythia, they went to Ruthenia in front of them with great joy, as soon as the news of their coming came to them. When the Hungarians took possession of Pannonia again, at the division of the country, with the consent of the Hungarians, these Székelys were given the part of the country that they had already chosen as their place of residence.

Early Modern period

The Old Hungarian script became part of folk art in several areas during this period. In Royal Hungary, Old Hungarian script was used less, although there are relics from this territory, too. There is another copy – similar to the Nikolsburg Alphabet – of the Old Hungarian alphabet, dated 1609. The inscription from Énlaka, dated 1668, is an example of the "folk art use".

There are a number of inscriptions ranging from the 17th to the early 19th centuries,[18] including examples from Kibéd, Csejd, Makfalva, Szolokma, Marosvásárhely, Csíkrákos, Mezőkeresztes, Nagybánya, Torda, Felsőszemeréd,[19] Kecskemét and Kiskunhalas.

Scholarly discussion

Hungarian script[20] was first described in late Humanist/Baroque scholarship by János Telegdy in his primer Rudimenta Priscae Hunnorum Linguae. Published in 1598, Telegdi's primer presents his understanding of the script and contains Hungarian texts written with runes, such as the Lord's Prayer.

In the 19th century, scholars began to research the rules and the other features of the Old Hungarian script. From this time, the name rovásírás ('runic writing') began to re-enter the popular consciousness in Hungary, and script historians in other countries began to use the terms "Old Hungarian", Altungarisch, and so on. Because the Old Hungarian script had been replaced by Latin, linguistic researchers in the 20th century had to reconstruct the alphabet from historic sources. Gyula Sebestyén, an ethnographer and folklorist, and Gyula (Julius) Németh, a philologist, linguist, and Turkologist, did the lion's share of this work. Sebestyén's publications, Rovás és rovásírás (Runes and runic writing, Budapest, 1909) and A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei (The authentic relics of Hungarian runic writing, Budapest, 1915) contain valuable information on the topic.

Popular revival

.JPG.webp)

Beginning with Adorján Magyar in 1915, the script has been promulgated as a means for writing modern Hungarian. These groups approached the question of representation of the vowels of modern Hungarian in different ways. Adorján Magyar made use of characters to distinguish a/á and e/é but did not distinguish the other vowels by length. A school led by Sándor Forrai from 1974 onward did, however, distinguish i/í, o/ó, ö/ő, u/ú, and ü/ű. The revival has become part of a significant ideological nationalist subculture present not only in Hungary (largely centered in Budapest), but also amongst the Hungarian diaspora, particularly in the United States and Canada.[21]

Old Hungarian has seen other usages in the modern period, sometimes in association with or referencing Hungarian neopaganism, similar to the way in which Norse neopagans have taken up the Germanic runes, and Celtic neopagans have taken up the ogham script for various purposes.

Controversies

Not all scholars agree with the "Old Hungarian" notion, mainly based on the actual literary facts. The linguist and sociolinguist Klára Sándor told in an interview that most of the "romantic" statements about the script appear to be false. According to her analysis, the origin of the writing is probably runiform (and with high probability its origins are in the western Turkic runiform writings) and it's not a different writing system and contrary to the sentiment the writing is neither Hungarian nor Székely-Hungarian; it is a Székely writing since there are no authentic findings outside the historic Székely lands (mainly today's Transylvania); the only writing found around 1000 AD had a different writing system. While it may have been sporadically used in Hungary its usage was not widespread. The "revived" writing (in the 1990s) was artificially expanded with (various) "new" letters which were unneeded in the past since the writing was cleanly phonetic, or the long vowels which were not present back in the time. The shape of many letters were substantially changed from the original. She stated that no works since 1915 has reached the expected quality of the state of the linguistic sciences, and many was influenced by various agendas.[22][23]

The use of the script often has a political undertone as it is often used along with irredentist or nationalist propaganda, and they can be found from time to time in graffiti with a variety of content.[21] Since most of the people cannot read the script it has led to various controversies, for example when the activists of the Hungarian Two-tailed Dog Party (opposition) exchanged the rovas sign of the city Érd to szia 'Hi!', which stayed unnoticed a month.[24]

Epigraphy

The inscription corpus includes:

- A labeled crest etched into stone from Pécs, late 13th century (Label: aBA SZeNTjeI vaGYUNK aKI eSZTeR ANna erZSéBeT; We are the saints [nuns] of Aba; who are Esther, Anna and Elizabeth.)

- Rod calendar, around 1300, copied by Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli in 1690.[25] It contains several feasts and names, thus it is one of the most extensive runic records.

- Nicholsburg alphabet[26]

- Runic record in Istanbul, 1515.[27]

- Székelyderzs: a brick with runic inscription, found in the Unitarian church

- Énlaka runic inscription, discovered by Balázs Orbán in 1864[26][28]

- Székelydálya: runic inscription, found in the Calvinist church

- The inscription from Felsőszemeréd (Horné Semerovce), Slovakia (15th century)

Characters

The runic alphabet included 42 letters. As in the Old Turkic script, some consonants had two forms, one to be used with back vowels (a, á, o, ó, u, ú) and another for front vowels (e, é, i, í, ö, ő, ü, ű). The names of the consonants are always pronounced with a vowel. In the old alphabet, the consonant-vowel order is reversed, unlike today's pronunciation (ep rather than pé). This is because the oldest inscriptions lacked vowels and were rarely written down, similar to other ancient languages' consonant-writing systems (Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic, etc.). The alphabet did not contain letters for the phonemes dz and dzs of modern Hungarian, since these are relatively recent developments in the language's history. Nor did it have letters corresponding to the Latin q, w, x and y. The modern revitalization movement has created symbols for these; in Unicode encoding, they are represented as ligatures.

For more information about the transliteration's pronunciation, see Hungarian alphabet.

| Letter | Name | Phoneme (IPA) | Old Hungarian (image) | Old Hungarian (Unicode) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | a | /ɒ/ⓘ | 𐲀 𐳀 | |

| Á | á | /aː/ⓘ | 𐲁 𐳁 | |

| B | eb | /b/ⓘ | 𐲂 𐳂 | |

| C | ec | /ts/ⓘ | 𐲄 𐳄 | |

| Cs | ecs | /tʃ/ | 𐲆 𐳆 | |

| D | ed | /d/ⓘ | 𐲇 𐳇 | |

| (Dz) | dzé | /dz/ⓘ | Ligature of 𐲇 and 𐲯 | |

| (Dzs) | dzsé | /dʒ/ | Ligature of 𐲇 and 𐲰 | |

| E | e | /ɛ/ⓘ | 𐲉 𐳉 | |

| É | é | /eː/ⓘ | 𐲋 𐳋 | |

| F | ef | /f/ⓘ | 𐲌 𐳌 | |

| G | eg | /ɡ/ⓘ | 𐲍 𐳍 | |

| Gy | egy | /ɟ/ⓘ | 𐲎 𐳎 | |

| H | eh | /h/ | 𐲏 𐳏 | |

| I | i | /i/ | 𐲐 𐳐 | |

| Í | í | /iː/ⓘ | 𐲑 𐳑 | |

| J | ej | /j/ⓘ | 𐲒 𐳒 | |

| K | ek | /k/ⓘ | 𐲓 𐳓 | |

| K | ak | /k/ⓘ | 𐲔 𐳔 | |

| L | el | /l/ⓘ | 𐲖 𐳖 | |

| Ly | elly, el-ipszilon | /j/ⓘ | 𐲗 𐳗 | |

| M | em | /m/ⓘ | 𐲘 𐳘 | |

| N | en | /n/ | 𐲙 𐳙 | |

| Ny | eny | /ɲ/ⓘ | 𐲚 𐳚 | |

| O | o | /o/ | 𐲛 𐳛 | |

| Ó | ó | /oː/ⓘ | 𐲜 𐳜 | |

| Ö | ö | /ø/ⓘ | 𐲝 𐳝 𐲞 𐳞 | |

| Ő | ő | /øː/ | 𐲟 𐳟 | |

| P | ep | /p/ⓘ | 𐲠 𐳠 | |

| (Q) | eq | (/kv/) | Ligature of 𐲓 and 𐲮 | |

| R | er | /r/ⓘ | 𐲢 𐳢 | |

| S | es | /ʃ/ⓘ | 𐲤 𐳤 | |

| Sz | esz | /s/ⓘ | 𐲥 𐳥 | |

| T | et | /t/ⓘ | 𐲦 𐳦 | |

| Ty | ety | /c/ⓘ | 𐲨 𐳨 | |

| U | u | /u/ | 𐲪 𐳪 | |

| Ú | ú | /uː/ⓘ | 𐲫 𐳫 | |

| Ü | ü | /y/ | 𐲬 𐳬 | |

| Ű | ű | /yː/ⓘ | 𐲭 𐳭 | |

| V | ev | /v/ⓘ | 𐲮 𐳮 | |

| (W) | dupla vé | /v/ⓘ | Ligature of 𐲮 and 𐲮 | |

| (X) | iksz | (/ks/) | Ligature of 𐲓 and 𐲥 | |

| (Y) | ipszilon | /i/ ~ /j/ | Ligature of 𐲐 and 𐲒 | |

| Z | ez | /z/ⓘ | 𐲯 𐳯 | |

| Zs | ezs | /ʒ/ⓘ | 𐲰 𐳰 |

The Old Hungarian runes also include some non-alphabetical runes which are not ligatures but separate signs. These are identified in some sources as "capita dictionum" (likely a misspelling of capita dicarum[29]). Further research is needed to define their origin and traditional usage. Some common examples are:

- TPRUS:

- ENT:

𐲧 𐳧

𐲧 𐳧 - TPRU:

- NAP:

- EMP:

𐲡 𐳡

𐲡 𐳡 - UNK:

𐲕 𐳕

𐲕 𐳕 - US:

𐲲 𐳲

𐲲 𐳲 - AMB:

𐲃 𐳃

𐲃 𐳃

Features

Old Hungarian letters were usually written from right to left on sticks. Later, in Transylvania, they appeared on several media. Writings on walls also were right to left and not boustrophedon style (alternating direction right to left and then left to right).

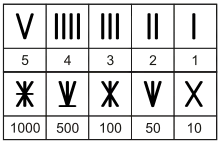

The numbers are almost the same as the Roman, Etruscan, and Chuvash numerals. Numbers of livestock were carved on tally sticks and the sticks were then cut in two lengthwise to avoid later disputes.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 | 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳺𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻 | 𐳻𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳻𐳺𐳺𐳺𐳺 | 𐳼 | 𐳽 | 𐳾 | ̲𐳽 | 𐳿 |

- Ligatures are common. (Note: the Hungarian runic script employed a number of ligatures. In some cases, an entire word was written with a single sign similar to a bind rune.) The Unicode standard supports ligatures explicitly by using the zero width joiner between the two characters.[30]

- There are no lower or upper case letters, but the first letter of a proper name was often written a bit larger. Though the Unicode standard has upper and lowercase letters, which are the same in shape, the difference is only their size.

- The writing system did not always mark vowels (similar to many Asian writing systems). The rules for vowel inclusion were as follows:

- If there are two vowels side by side, both have to be written, unless the second could be readily determined.

- The vowels have to be written if their omission created ambiguity. (Example: krk –

.svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) can be interpreted as kerék –

can be interpreted as kerék – .svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) (wheel) and kerek –

(wheel) and kerek – .svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

_JB.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp) (rounded), thus the writer had to include the vowels to differentiate the intended words.)

(rounded), thus the writer had to include the vowels to differentiate the intended words.) - The vowel at the end of the word must be written.

- Sometimes, especially when writing consonant clusters, a consonant was omitted. This is a phonologic process, with the script reflecting the exact surface realization.

Text example

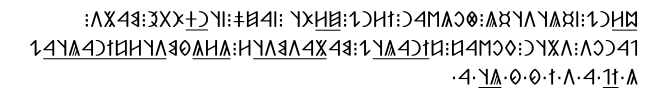

Text from Csíkszentmárton, 1501. Runes originally written as ligatures are underlined.

Unicode transcription: 𐲪𐲢𐲙𐲔⁝𐲥𐲬𐲖𐲦𐲤𐲦𐲬𐲖⁝𐲌𐲛𐲍𐲮𐲀𐲙⁝𐲐𐲢𐲙𐲔⁝𐲯𐲢𐲞𐲦 ⁝𐲥𐲀𐲯𐲎⁝𐲥𐲦𐲙𐲇𐲞𐲂𐲉⁝𐲘𐲀𐲨𐲤⁝𐲒𐲀𐲙𐲛𐲤⁝𐲤𐲨𐲦𐲙⁝𐲓𐲛𐲮𐲀𐲆⁝𐲆𐲐𐲙𐲀𐲖𐲦𐲔⁝𐲘𐲀𐲨𐲀𐲤𐲘𐲤𐲦𐲢⁝𐲍𐲢𐲍𐲗𐲘𐲤𐲦𐲢𐲆𐲐𐲙𐲀𐲖𐲦𐲀𐲔 𐲍·𐲐𐲒·𐲀·𐲤·𐲐·𐲗·𐲗·𐲖𐲦·𐲀·

Interpretation in old Hungarian: "ÚRNaK SZÜLeTéSéTÜL FOGVÁN ÍRNaK eZeRÖTSZÁZeGY eSZTeNDŐBE MÁTYáS JÁNOS eSTYTáN KOVÁCS CSINÁLTáK MÁTYáSMeSTeR GeRGeLYMeSTeRCSINÁLTÁK G IJ A aS I LY LY LT A" (The letters actually written in the runic text are written with uppercase in the transcription.)

Interpretation in modern Hungarian: "(Ezt) az Úr születése utáni 1501. évben írták. Mátyás, János, István kovácsok csinálták. Mátyás mester (és) Gergely mester csinálták gijas ily ly lta"

English translation: "(This) was written in the 1501st year of our Lord. The smiths Matthias, John (and) Stephen did (this). Master Matthias (and) Master Gregory did (uninterpretable)

Unicode

After many proposals[31] Old Hungarian was added to the Unicode Standard in June, 2015 with the release of version 8.0.

The Unicode block for Old Hungarian is U+10C80–U+10CFF:

| Old Hungarian[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+10C8x | 𐲀 | 𐲁 | 𐲂 | 𐲃 | 𐲄 | 𐲅 | 𐲆 | 𐲇 | 𐲈 | 𐲉 | 𐲊 | 𐲋 | 𐲌 | 𐲍 | 𐲎 | 𐲏 |

| U+10C9x | 𐲐 | 𐲑 | 𐲒 | 𐲓 | 𐲔 | 𐲕 | 𐲖 | 𐲗 | 𐲘 | 𐲙 | 𐲚 | 𐲛 | 𐲜 | 𐲝 | 𐲞 | 𐲟 |

| U+10CAx | 𐲠 | 𐲡 | 𐲢 | 𐲣 | 𐲤 | 𐲥 | 𐲦 | 𐲧 | 𐲨 | 𐲩 | 𐲪 | 𐲫 | 𐲬 | 𐲭 | 𐲮 | 𐲯 |

| U+10CBx | 𐲰 | 𐲱 | 𐲲 | |||||||||||||

| U+10CCx | 𐳀 | 𐳁 | 𐳂 | 𐳃 | 𐳄 | 𐳅 | 𐳆 | 𐳇 | 𐳈 | 𐳉 | 𐳊 | 𐳋 | 𐳌 | 𐳍 | 𐳎 | 𐳏 |

| U+10CDx | 𐳐 | 𐳑 | 𐳒 | 𐳓 | 𐳔 | 𐳕 | 𐳖 | 𐳗 | 𐳘 | 𐳙 | 𐳚 | 𐳛 | 𐳜 | 𐳝 | 𐳞 | 𐳟 |

| U+10CEx | 𐳠 | 𐳡 | 𐳢 | 𐳣 | 𐳤 | 𐳥 | 𐳦 | 𐳧 | 𐳨 | 𐳩 | 𐳪 | 𐳫 | 𐳬 | 𐳭 | 𐳮 | 𐳯 |

| U+10CFx | 𐳰 | 𐳱 | 𐳲 | 𐳺 | 𐳻 | 𐳼 | 𐳽 | 𐳾 | 𐳿 | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Pre-Unicode encodings

A set of closely related 8-bit code pages exist, devised in the 1990s by Gabor Hosszú. These were mapped to Latin-1 or Latin-2 character set fonts. After installing one of them and applying their formatting to the document – because of the lack of capital letters – runic characters could be entered in the following way: those letters which are unique letters in today's Hungarian orthography are virtually lowercase ones, and can be written by simply pressing the specific key; and since the modern digraphs equal to separate rovás letters, they were encoded as 'uppercase' letters, i.e. in the space originally restricted for capitals. Thus, typing a lowercase g will produce the rovás character for the sound marked with Latin script g, but entering an uppercase G will amount to a rovás sign equivalent to a digraph gy in Latin-based Hungarian orthography.

Gallery

Stone Shield pattern of Pécs with Old Hungarian Script (circa 1250 AD), Hungary

Stone Shield pattern of Pécs with Old Hungarian Script (circa 1250 AD), Hungary Rovás inscription from Homoródkarácsonyfalva, 13th century

Rovás inscription from Homoródkarácsonyfalva, 13th century Inscription in Énlaka's Unitarian church (1668)

Inscription in Énlaka's Unitarian church (1668)

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Consolidated proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-31.

- ↑ "ISO 15924/RA Notice of Changes". ISO 15924. Archived from the original on 2012-10-30.

- ↑ Code request for the Rovas script in ISO 15924 (2012-10-20)

- 1 2 ⓘ

- ↑ by the public. From the verb ró 'to carve', 'to score' since the letters were usually carved on wood or sticks.

- ↑ Róna-Tas (1987, 1988)

- ↑ András Róna-Tas: On the Development and Origin of the East Turkic "Runic" Script (In: Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungariae XLI (1987), p. 7-14

- ↑ Franz Altheim: Geschichte der Hunnen, vol. 1, p. 118

- ↑ Új Magyar Lexikon (New Hungarian Encyclopaedia) – Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1962. (Volume 5) ISBN 963-05-2808-8

- ↑ András Róna-Tas A magyar írásbeliség török eredetéhez (In: Klára Sándor (ed.) Rovás és Rovásírás p.9–14 — Szeged, 1992, ISBN 963-481-885-4)

- ↑ István Fodor – György Diószegi – László Legeza: Őseink nyomában. (On the scent of our ancestors) – Magyar Könyvklub-Helikon Kiadó, Budapest, 1996. ISBN 963-208-400-4 (Page 82)

- ↑ Dóra Tóth-Károly Bera: Honfoglalás és őstörténet. Aquila, Budapest, 1996. ISBN 963-8276-96-7

- ↑ Bodor, György: A blakok. In: Viktor Szombathy and Gyula László (eds.), Magyarrá lett keleti népek. Budapest, 1988, pp. 56–60.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Láczay Ervin (2005), "A honfoglaláskori erdélyi blak, vagy bulák nép török eredete" (PDF), Acta Historica Hungarica Turiciensia: 161–177, ISBN 9639349100

- 1 2 Johannes Thuróczy: Chronica Hungarorum http://thuroczykronika.atw.hu/pdf/Thuroczy.pdf

- ↑ Simon of Kéza: Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum https://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02249/02249.htm

- ↑ Hosszú, Gábor (2013). Heritage of Scribes. The Relation of Rovas Scripts to Eurasian Writing Systems. Budapest. ISBN 978-963-88-4374-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Felvidék.Ma (4 September 2023). "Sokol érsek 75 éves – nyugdíj Sokolnak, nyugalom a magyaroknak? - Felvidék.ma".

- ↑ Diringer, David. 1947. The Alphabet. A Key to the History of Mankind. London: Hutchinson's Scientific and technical Publications, pp. 314-315. Gelb, I. J. 1952. A study of writing: The foundations of grammatology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 142, 144. Gaur, Albertine. 1992. A History of Writing. London: British Library. ISBN 0-7123-0270-0. pp. 143. Coulmas, Florian. 1996. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. ISBN 0-631-19446-0. pp. 366-368

- 1 2 Maxwell, Alexander (2004). "Contemporary Hungarian Rune-Writing: Ideological Linguistic Nationalism within a Homogenous Nation", Anthropos, 99: 2004, pp. 161-175

- ↑ "Mit kezdjünk a rovásírással?" [What shall we do with rovas?] (in Hungarian). vaskarika.hu. 2019-09-12. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ László Fejes (2010-10-25). "Ősmagyar örökség? Humanista hamisítvány?" [Ancient Hungarian Heritage? Humanist Hoax?] (in Hungarian). Nyest.hu. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ "Egy hónapig senkinek se tűnt fel, hogy lecserélték Érd rovásírásos tábláját" [Nobody have noticed for a month that the rovas sign of Érd was replaced] (in Hungarian). 444.hu. 2017-04-24. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ↑ Klára Sándor: A bolognai rovásemlék, Szeged, 1991; ISBN 963-481-870-6

- 1 2 "ROVÁS.hu - A régi magyar írás - Irodalom - Rovásírásos emlékek". www.rovas.hu. Archived from the original on 22 June 2006. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ↑ Doblhofer, Ernst (1971). Voices in stone : the decipherment of ancient scripts and writings. Collier. p. 289. OCLC 221819485.

- ↑ "ROVÁS.hu - A régi magyar írás - Képek rólunk". 30 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ↑ "Rovásírás ROVÁSÍRÁS Csudabogarak". Archived from the original on 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2017-09-24.

- ↑ "True Ligatures" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-07-31.

- ↑ Old Hungarian/Szekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad Hoc Committee: Old Hungarian/Sekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad hoc Report Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-11-12

- Jenő Demeczky, György Giczi, Gábor Hosszú, Gergely Kliha, Borbála Obrusánszky, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: About the consensus of the Rovas encoding – Response to N4373 (Resolutions of the 8th Hungarian World Congress on the encoding of Old Hungarian). Registered by UTC (L2/12-337), 2012-10-24

- György Gergely Gyetvay (World Federation of Hungarians): Resolutions of the 8th Hungarian World Congress on the encoding of Old Hungarian Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-22

- Jenő Demeczky, György Giczi, Gábor Hosszú, Gergely Kliha, Borbála Obrusánszky, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: Additional information about the name of the Rovas script Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-21.

- Jenő Demeczky, Gábor Hosszú, Tamás Rumi, László Sípos, Erzsébet Zelliger: Revised proposal for encoding the Rovas in the UCS Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-10-14.

- Tamás Somfai: Contemporary Rovas in the word processing Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-05-25

- Michael Everson & André Szabolcs Szelp: Consolidated proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS Archived 2012-12-03 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-05-06

- Miklós Szondi (president of the "Természetesen" society and chair of the "Egységes rovás" conference) Declaration of Support for the Advancement of the Encoding of the old Hungarian Script Archived 2015-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-04-28

- Gábor Hosszú (Hungarian National Body): Code chart font for Rovas block Archived 2012-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-02-06

- André Szabolcs Szelp: Remarks on Old Hungarian and other scripts with regard to N4183 Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-01-30

- Michael Everson (Irish National Body): Code chart fonts for Old Hungarian Archived 2012-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, 2012-01-28

- Gábor Hosszú (Hungarian National Body): Proposal for encoding the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas, Carpathian Basin Rovas and Khazarian Rovas scripts into the Rovas block in the SMP of the UCS Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-12-15

- Hungarian Runic/Szekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad Hoc Committee: Hungarian Runic/Sekely-Hungarian Rovas Ad-hoc Report Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-06-08

- Gábor Hosszú: Issues of encoding the Rovas scripts Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-25

- Gábor Hosszú: Comments on encoding the Rovas scripts Archived 2011-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-22

- Gábor Hosszú: Revised proposal for encoding the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script in the SMP of the UCS Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-21

- Gábor Hosszú: Notes on the Szekely-Hungarian Rovas script Archived 2011-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-15

- Michael Everson & André Szabolcs Szelp: Mapping between Hungarian Runic proposals in N3697 and N4007 Archived 2011-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-08

- Deborah Anderson: Comparison of Hungarian Runic and Szekely‐Hungarian Rovas proposals Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, 2011-05-07

- Deborah Anderson: Outstanding Issues on Old Hungarian/Szekler‐Hungarian Rovas/Hungarian Native Writing Archived 2012-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2009-04-22

- Michael Everson: Mapping between Old Hungarian proposals in N3531, N3527, and N3526 Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-11-02

- Michael Everson and Szabolcs Szelp: Revised proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS = Javított előterjesztés a rovásírás Egyetemes Betűkészlet-beli kódolására) Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-10-12

- Gábor Hosszú: Proposal for encoding the Szekler-Hungarian Rovas in the BMP and the SMP of the UCS Archived 2008-12-21 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-10-04

- Gábor Bakonyi: Hungarian native writing draft proposal Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-09-30

- Michael Everson and Szabolcs Szelp: Preliminary proposal for encoding the Old Hungarian script in the UCS Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, 2008-08-04

- Michael Everson: On encoding the Old Hungarian rovásírás in the UCS Archived 2006-06-21 at the Wayback Machine, 1998-05-02

- Michael Everson: Draft Proposal to encode Old Hungarian in Plane 1 of ISO/IEC 10646-2 Archived 2008-09-08 at the Wayback Machine, 1998-01-18

References

English

- Gábor Hosszú (2011): Heritage of Scribes. The Relation of Rovas Scripts to Eurasian Writing Systems. First edition. Budapest: Rovas Foundation, ISBN 978-963-88437-4-6, fully available from Google Books

- Edward D. Rockstein: "The Mystery of the Székely Runes", Epigraphic Society Occasional Papers, Vol. 19, 1990, pp. 176–183

Hungarian

- Új Magyar Lexikon (New Hungarian Encyclopaedia) – Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 1962 (Volume 5) ISBN 963-05-2808-8

- Gyula Sebestyén: A magyar rovásírás hiteles emlékei, Budapest, 1915

Latin

- J. Thelegdi: Rudimenta priscae Hunnorum linguae brevibus quaestionibus et responsionibus comprehensa, Batavia, 1598

External links

![]() Media related to Old Hungarian script at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Old Hungarian script at Wikimedia Commons

- Hungarian Runes / Rovás on Omniglot

- (in Hungarian and English) Rovásírás (Gábor Hosszú)

- (in Hungarian) Kiszely István: A magyar nép őstörténete

- (in Hungarian) Learning Rovas

- (in Hungarian) The Living Rovas

- (in Hungarian) Hungarian Rovas Portal

- (in Hungarian) Szekely-Hungarian Rovas

- Szekely-Hungarian Rovas on RovasPedia

- Old Hungarian Unicode fonts

- ALPHABETUM by Juan José Marcos (commercial font)

- Noto Sans Old Hungarian

- Old Hungarian by Zsolt Sz. Sztupák

- OptimaModoki by Dare-demo Iie

- TWB01x SMP fonts by Thomas Buchleither (archived on 2019-07-17)