Ruins of the pavilion at Piazza Sallustio | |

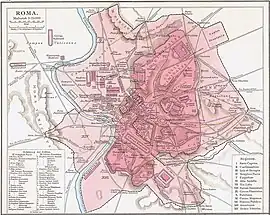

Gardens of Sallust Shown within Augustan Rome | |

| Coordinates | 41°54′29.1″N 12°29′48.9″E / 41.908083°N 12.496917°E |

|---|---|

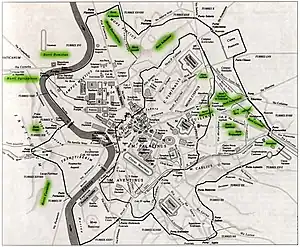

The Gardens of Sallust (Latin: Horti Sallustiani) was an ancient Roman estate including a landscaped pleasure garden developed by the historian Sallust in the 1st century BC.[1] It occupied a large area in the northeastern sector of Rome, in what would become Region VI, between the Pincian and Quirinal hills, near the Via Salaria and later Porta Salaria. The modern rione is now known as Sallustiano.

History

The horti in ancient Rome

Lucullus started the fashion of building luxurious garden-palaces in the 1st century BC with the construction of his gardens (horti) on the Pincian Hill. The horti were a place of pleasure, almost a small palace, and offered the rich owner and his court the possibility of living in isolation, away from the hectic life of the city but close to it. The most important part of the horti was undoubtedly the planting, very often as topiary in geometric or animal shapes. Among the greenery there were often pavilions, arcades for walking away from the sun, fountains, spas, temples and statues, often replicas of Greek originals.

In the 3rd century AD the total number of horti occupied about a tenth of Rome and formed a green belt around the centre.

The Horti Sallustiani

The property originally belonged to Julius Caesar as the Horti Caesaris,[2] but after his death it was acquired by the historian Sallust, one of his closest friends, who developed it using his wealth acquired as governor of the province of Africa Nova (newly conquered Numidia). In 36 BC on the death of the historian, the residence passed to his adopted great-grandson of the same name, and eventually to Claudius as imperial property[3][4] but was maintained for several centuries by the Roman Emperors as a public amenity.[5] The gardens were enriched with many additional structures and monumental sculptures in the four centuries during which they evolved. Many emperors chose it as a temporary residence, as an alternative to the official seat on the Palatine Hill.

Pliny writes that the remains of the guardians of the horti, Posio and Secundilla, were found there in the reign of Augustus and measured 10 feet 3 inches tall.[6]

The Emperor Nerva died of a fever in the villa of the horti in 98, and the emperors Hadrian and Aurelian had major works done there. The latter in particular had a porticus miliarensis built, probably a complex of portico, garden and riding stables, where he went to ride. Other restorations were carried out in the third century.

It remained an imperial resort until it was sacked in 410 by the Goths under Alaric, who entered the city at the gates of the Horti Sallustiani. The complex was severely damaged and never rebuilt.[7] However, the gardens were not finally deserted until the 6th century.[8]

Discoveries

During the planting of 16th century vineyards and especially in the early 17th century when Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi, nephew of Pope Gregory XV, purchased the site and constructed the Villa Ludovisi, many important sculptures were discovered.

In the late 19th century the building fever of the construction of Rome as the capital included the destruction of modern villas that populated the Quirinale. It was a lost opportunity to study the archaeology of the site. The ancient topography was irrevocably altered with the filling of the valley between the Pincio and Quirinal hills where these horti existed.[9]

Nevertheless, excavations led to the partial discovery of a nymphaeum probably dating from Hadrian's renovation of the horti. Its walls were encrusted with enamels, pumice and shells, which framed small landscapes and scenes with animals and flowers painted in bright colours. The sculptural decoration included a round altar with four Seasons and the beautiful group of Artemis and Iphigenia with a doe, now in Copenhagen.

Also part of the later complex was the temple of Venus Erycina which stood at the bottom of the valley, a Republican building located just outside the Porta Collina and incorporated in the horti under Caesar. This small temple was reminiscent of a Hellenistic tholos, a very common type in the late Republican age and a typical element of large suburban villas. The connection to Venus, goddess of love, fertility and nature, and therefore protector of horti suited a large villa such as the Sallustian.

The horti also housed a hippodrome (circus) built by Aurelian.[10]

Remains

A remarkably well-preserved pavilion of the villa can be seen at the centre of present-day Piazza Sallustio, 14 m below present street level. It was probably a summer triclinium like the Serapeum of Hadrian's Villa. The main part of the building was a large circular hall (11 m in diameter by 13 in height), covered by a dome with alternating concave and flat segments (a very rare form, found only in the Serapeum). The walls host three niches on each side, two of which were open as passages for side rooms, probably nymphaea. A few years after construction, the remaining niches were closed and covered with marble panels, which also covered the walls. The floor was also marble, while the dome and the upper part of the walls were decorated with stucco. A grandiose basilica room was framed by two side buildings on two floors, while the upper part of the building had a large panoramic terrace, linked to a gallery.

It was one of the main nuclei in a spectacular location at the bottom of the valley dividing the Quirinale from the Pincio. It was supported by thick walls with arches and buttresses resting on the Servian Walls where the Via Sallustiana runs today, and resting against the hill behind and connected to other remains of poorly preserved buildings.

To the south there is a semi-circular covered room divided into three areas with partitions, two of which still retain ancient mosaics in black and white and the remains of wall paintings probably from a later time; the third room towards the south is occupied by a flight of stairs to the two upper floors, while the north one was interspersed with an room used as a latrine.

The brick stamps of this building confirm a date of 126. The dating is significant because it shows the developments of imperial private architecture after the Domus Augustana, and the evolution from the Domus Aurea model over nearly 50 years.

Among the other remains in the complex is a cryptoporticus with wall paintings, now in the garage of the American Embassy on the side on via Friuli, and a wall with niches along via Lucullo. A large Hadrianic cistern also survives under Collegio Germanico at the corner of Via San Nicola da Tolentino and Via Bissolati[11] consisting of two levels: the first, 1.8 m high, acts as a substructure to the second (overall 39 x 3.3 m).

Art

.jpg.webp)

Testimony of the importance and wealth of the Horti Sallustiani are the great works of art found, many of them ancient Greek originals, even though numerous robberies took place over the centuries.

The sculpture found in the 16th and 17th centuries included:

- the colossal acrolith of a large female head called Acrolito Ludovisi, a divinity of Magna Graecia

- the group of Gauls including the Dying Gaul, Ludovisi Gaul and the Kneeling Gaul

- Orestes and Electra signed by Menelaos, 1st c. BC

- great herms depicting Heracles, Dionysus, Athena, Theseus, Hermes, a discus thrower

- the Borghese Hermaphrodite.

Almost all the works found in the late 19th century were sold to the great collectors of Europe and America, first of all Jacobsen, founder of the Glyptothek of Copenhagen, with the mediation of antique and art dealers who worked for illicit export, violating the Pacca edict on the protection of the works found. Later work of identifying numerous works preserved in Italian and foreign museums has made it possible to trace them back to the Horti Sallustiani.[12]

The works found later[13] included:

- the Obelisco Sallustiano, a Roman copy of an Egyptian obelisk which now stands in front of the Trinità dei Monti church above the Piazza di Spagna at the top of the Spanish Steps

- the Borghese Vase discovered there in the 16th century.

- the Ludovisi Throne found in 1887, and the Boston Throne, found in 1894 between via Sicilia and the intersection with via Abruzzi

- the Crouching Amazon found in 1888 near the via Boncompagni, about 25 m from the via Quintino Sella (Museo Conservatori).

- two refined colossi of Pharaoh Ptolemy II and Queen Arsinoe II, now in the Egyptian Gregorian Museum

- the dying Niobid

- Artemis and Iphigenia from the nymphaeum.

The Niobid, an original of the 5th century BC, is believed be one of the numerous works brought to Rome from Greece by Augustus as spoils of war and which played a large part in the evolution of the taste and style of Roman art. It is similar to the figures of the pediment of the temple of Apollo Daphnephoros in Eretria and perhaps is also linked to the dying Niobid and the running Niobid of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen. The Niobid should have decorated the pediment of a Greek temple but was found hidden to save it from the barbarian raids that devastated the area in the 5th century AD.

The Nike Ludovisi and the famous Ludovisi Throne,[14] both Greek originals brought to Rome, may have been placed in the Temple of Venus Erycina which was later incorporated into the horti. The throne came from the sanctuary of Aphrodite (Venus) at Locri; in 1982 it was shown to fit exactly into remaining blocks in the temple's foundations. Some verses of Ovid suggest the transfer of the cult statue from Magna Graecia to Rome.

.jpg.webp) Obelisk Sallustiano on the Spanish Steps

Obelisk Sallustiano on the Spanish Steps_-_Arte_Ellenistica_Greca_-_Copia_Romana_-_Photo_Paolo_Villa_FO232046_ombre_gimp_bis.jpg.webp) Ludovisi Gaul (Palazzo Altemps)

Ludovisi Gaul (Palazzo Altemps) Dying Gaul (Capitoline Museum entered by way of the Campidoglio)

Dying Gaul (Capitoline Museum entered by way of the Campidoglio) Kneeling Gaul (Louvre)

Kneeling Gaul (Louvre) Dying Niobid discovered in 1906 (Museo Nazionale Romano

Dying Niobid discovered in 1906 (Museo Nazionale Romano

Ludovisi Throne (Palazzo Altemps)

Ludovisi Throne (Palazzo Altemps)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Emilia Talamo, Horti Sallustiani, in Horti Romani, Roma, 1995.

- ↑ Richardson, Lawrence, Jr., 1920-2013. A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-4300-6. OCLC 25009118

- ↑ Tac. Ann. XIII.47

- ↑ CIL VI.5863

- ↑ The Correspondence of Paul and Seneca, From "The Apocryphal New Testament" M.R. James-Translation and Notes Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1924

- ↑ Walter L. Pyle, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, Chapter VII. Anomalies of Stature, Size, and Development.

- ↑ Procopius.

- ↑ Miranda Marvin, "The Ludovisi Barbarians: The Grand Manner", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes, 1, "The Ancient Art of Emulation" (2002:205-223) p. 205 and note 9.

- ↑ Hartswick 2004.

- ↑ Hist. Aug: Aurel. 49

- ↑ Coarelli 2007.

- ↑ Emilia Talamo, Gli Horti di Sallustio a Porta Collina, in Maddalena Cima, Eugenio La Rocca (a cura di), 1998, Horti romani, Atti del convegno internazionale (Roma, 4-6 maggio 1995), Roma, L'Erma di Bretschneider, 1998

- ↑ T. Ashby, "Recent Excavations in Rome", CQ 2/2 (1908) p.49.

- ↑ Melissa M. Terras, 1997. "The Ludovisi and Boston Throne: a Comparison" A thorough website entirely devoted to the Ludovisi Throne and the Boston Throne http://darkroomtheband.net/collective/thrones/htm/

References

- Samuel Ball Platner and Thomas Ashby, 1929. A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, (Oxford University Press): Horti Sallustiani

- Kim J. Hartswick, 2004. The Gardens of Sallust: A Changing Landscape (University of Texas Press) Reviewed by Eric M. Moormann, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 20 The first monograph on the subject, covering topography and history, architecture and sculpture.

- The Gardens of Sallust from Platner/Ashby's Topographical Dictionary

- Filippo Coarelli: Rome and Environs. An Archaeological Guide. University of California Press, 2007. pp. 242–244

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

![]() Media related to Horti Sallustiani (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Horti Sallustiani (Rome) at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Gardens of Maecenas |

Landmarks of Rome Gardens of Sallust |

Succeeded by Stadium of Domitian |