| Hofmann rearrangement | |

|---|---|

| Named after | August Wilhelm von Hofmann |

| Reaction type | Rearrangement reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000410 |

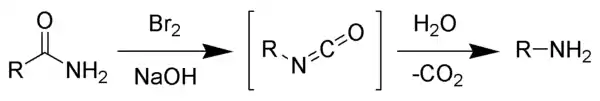

The Hofmann rearrangement (Hofmann degradation) is the organic reaction of a primary amide to a primary amine with one less carbon atom.[1][2][3] The reaction involves oxidation of the nitrogen followed by rearrangement of the carbonyl and nitrogen to give an isocyanate intermediate. The reaction can form a wide range of products, including alkyl and aryl amines.

The reaction is named after its discoverer, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, and should not be confused with the Hofmann elimination, another name reaction for which he is eponymous.

Mechanism

The reaction of bromine with sodium hydroxide forms sodium hypobromite in situ, which transforms the primary amide into an intermediate isocyanate. The formation of an intermediate nitrene is not possible because it implies also the formation of a hydroxamic acid as a byproduct, which has never been observed. The intermediate isocyanate is hydrolyzed to a primary amine, giving off carbon dioxide.[2]

- Base abstracts an acidic N-H proton, yielding an anion.

- The anion reacts with bromine in an α-substitution reaction to give an N-bromoamide.

- Base abstraction of the remaining amide proton gives a bromoamide anion.

- The bromoamide anion rearranges as the R group attached to the carbonyl carbon migrates to nitrogen at the same time the bromide ion leaves, giving an isocyanate.

- The isocyanate adds water in a nucleophilic addition step to yield a carbamic acid (aka urethane).

- The carbamic acid spontaneously loses CO2, yielding the amine product.

Variations

Several reagents can be substituted for bromine. Sodium hypochlorite,[4] lead tetraacetate,[5] N-bromosuccinimide, and (bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo)benzene[6] can affect a Hofmann rearrangement.

The intermediate isocyanate can be trapped with various nucleophiles to form stable carbamates or other products rather than undergoing decarboxylation. In the following example, the intermediate isocyanate is trapped by methanol.[7]

In a similar fashion, the intermediate isocyanate can be trapped by tert-butyl alcohol, yielding the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc)-protected amine.

The Hofmann Rearrangement also can be used to yield carbamates from α,β-unsaturated or α-hydroxy amides[2][8] or nitriles from α,β-acetylenic amides[2][9] in good yields (≈70%).

Applications

- In the preparation of anthranilic acid from phthalimide[10]

- Nicotinamide is converted into 3-Aminopyridine[11]

- The symmetrical structure of α-phenyl propanamide does not change after Hofmann reaction.

- In the synthesis of gabapentin, beginning with the mono-amidation of 1,1-cyclohexane diacetic acid anhydride with ammonia to 1,1-cyclohexane diacetic acid mono-amide, followed by a Hofmann rearrangement[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Hofmann, A. W. (1881). "Ueber die Einwirkung des Broms in alkalischer Lösung auf Amide" [On the action of bromine in alkaline solution on amides]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 14 (2): 2725–2736. doi:10.1002/cber.188101402242.

- 1 2 3 4 Everett, Wallis; Lane, John (1946). The Hofmann Reaction. Vol. 3. pp. 267–306. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or003.07. ISBN 9780471005285.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ↑ Shioiri, Takayuki (1991). "Degradation Reactions". Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Vol. 6. pp. 795–828. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-052349-1.00172-4. ISBN 9780080359298.

- ↑ Mohan, Ram S.; Monk, Keith A. (1999). "The Hofmann Rearrangement Using Household Bleach: Synthesis of 3-Nitroaniline". Journal of Chemical Education. 76 (12): 1717. Bibcode:1999JChEd..76.1717M. doi:10.1021/ed076p1717.

- ↑ Baumgarten, Henry; Smith, Howard; Staklis, Andris (1975). "Reactions of amines. XVIII. Oxidative rearrangement of amides with lead tetraacetate". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 40 (24): 3554–3561. doi:10.1021/jo00912a019.

- ↑ Almond, Merrick R.; Stimmel, Julie B.; Thompson, Alan; Loudon, Marc (1988). "Hofmann Rearrangement under Mildly Acidic Conditions using [I,I-Bis(Trifluoroacetoxy)]iodobenzene: Cyclobutylamine Hydrochloride from Cyclobutanecarboxamide". Organic Syntheses. 66: 132. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.066.0132.

- ↑ Keillor, Jeffrey W.; Huang, Xicai (2002). "Methyl Carbamate Formation via Modified Hofmann Rearrangement Reactions: Methyl N-(p-Methoxyphenyl)carbamate". Organic Syntheses. 78: 234. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.078.0234.

- ↑ Weerman, R.A. (1913). "Einwirkung von Natriumhypochlorit auf Amide ungesättigter Säuren". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 401 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1002/jlac.19134010102.

- ↑ Rinkes, I. J. (1920). "De l'action de l'Hypochlorite de Sodium sur les Amides D'Acides". Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas. 39 (12): 704–710. doi:10.1002/recl.19200391204.

- ↑ Maki, Takao; Takeda, Kazuo (2000). "Benzoic Acid and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_555. ISBN 3527306730..

- ↑ Allen, C. F. H.; Wolf, Calvin N. (1950). "3-Aminopyridine". Organic Syntheses. 30: 3. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.030.0003.; Collective Volume, vol. 4, p. 45

- ↑ US 20080103334, "Process For Synthesis Of Gabapentin"

Bibliography

- Clayden, Jonathan (2007). Organic Chemistry. Oxford University Press Inc. pp. 1073. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- Fieser, Louis F. (1962). Advanced Organic Chemistry. Reinhold Publishing Corporation, Chapman & Hall, Ltd. pp. 499–501.