| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

The history of video game consoles, both home and handheld, began in the 1970s. The first console that played games on a television set was the 1972 Magnavox Odyssey, first conceived by Ralph H. Baer in 1966. Handheld consoles originated from electro-mechanical games that used mechanical controls and light-emitting diodes (LED) as visual indicators. Handheld electronic games had replaced the mechanical controls with electronic and digital components, and with the introduction of Liquid-crystal display (LCD) to create video-like screens with programmable pixels, systems like the Microvision and the Game & Watch became the first handheld video game consoles.

Since then, home game consoles have progressed through technology cycles typically referred to as generations. Each generation has lasted approximately five years, during which the major console manufacturers have released console with broadly similar specifications. Handheld consoles have seen similar advances, and are usually grouped into the same generations as home consoles.

While early generations were led by manufacturers like Atari and Sega, the modern home console industry is dominated by three companies: Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft. The handheld market has waned since the introduction of mobile gaming in the mid-2000s, and today, the only major manufacturer in handheld gaming is Nintendo.

Origins

Home consoles

The first video games were created on mainframe computers in the 1950s, typically with text-only displays or computer printouts, and limited to simple games like Tic Tac Toe or Nim.[1] Eventually displays with rudimentary vector displays for graphics were available, leading to titles like Spacewar! in 1962.[2] Spacewar! directly influenced Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney to create Computer Space in 1971, the first recognized arcade game.[3]

Separately, while at Sanders Associates in 1966, Ralph H. Baer conceived of the idea of an electronic device that could be connected to a standard television to play games. With Sanders' permission, he created the prototype "Brown Box" which was able to play a limited number of games, including a version of table tennis and a simple light gun game. Sanders patented the unit and licensed the patents to Magnavox, where it was manufactured as the first home video game console, the Magnavox Odyssey, in 1972.[4] Bushnell, after seeing the Odyssey and its table tennis game, believed he could make something better. He and Dabney formed Atari, Inc., and with Allan Alcorn, created their second arcade game, Pong. Pong first released in 1972 and was more successful than Computer Space.[5] Atari released a Pong home console through Sears in 1975.[6]

Handheld consoles

The origins of handheld game consoles are found in handheld and tabletop electronic game devices of the 1970s and early 1980s. These electronic devices can only play built-in games,[7] they fit in the palm of the hand or on a tabletop, and they may make use of a variety of video display technologies such as LED, VFD, or LCD.[8] These games derived from the emerging optoelectronic-display-driven calculator market of the early 1970s.[9][10]

The first such handheld electronic game was released by Mattel in 1977, where Michael Katz, Mattel's new product category marketing director, told the engineers in the electronics group to design a game the size of a calculator, using LED technology."[11] This effort led to the 1977 games Auto Race[12] and Football.[13][14] The two games were so successful that according to Katz, "these simple electronic handheld games turned into a '$400 million category.'"[8] Another Ralph Baer invention, Simon, published by Milton Bradley in 1978, followed, which further popularized such electronic games and remained an enduring property by Milton Bradley (later Hasbro) that brought a number of copycats to the market.[15][16] Soon, other manufacturers including Coleco, Parker Brothers, Entex, and Bandai began following up with their own tabletop and handheld electronic games.[17]

The transition from handheld "electronic" games to handheld "video" games came with the introduction of LCD screens. These screens gave handheld games the flexibility to play a wide range of games. Milton Bradley's Microvision, released in 1979, used a 16x16 pixel LCD screen and was the first handheld to use interchangeable game cartridges.[18][19]

Nintendo's line of Game & Watch titles, first introduced in 1980, was designed by Gunpei Yokoi, who was inspired when he saw a man passing time on a train by playing with an LCD calculator.[20][21] Taking advantage of the technology used in the credit-card-sized calculators that had appeared on the market, Yokoi designed the series of LCD-based games to include a digital time display in the corner of the screen, so that they could double as a watch.[22] While the Game & Watch series were considered handheld electronic games rather than handheld video game consoles, their success led Nintendo, through Yokoi's design lead, to produce the Game Boy in 1989.[23]

Console generations

The history of video game consoles are typically segmented into "generations" which are used to group consoles that have shared a competitive market.[24][25] These console generations typically last about five years, following a Moore's law progression where processing power increased by 10 times roughly every five years.[26][27] This cyclic market has resulted in an industry-wide adoption of the razorblade model, where companies sell consoles at a small profit while making the bulk of their money from selling games. The companies then transition users to their new console as the new generation comes on line, using a form of planned obsolescence.[28]

The exact start and end of each console generation is not consistently defined. Some schemes have been based on direct market data (including a seminal work published in an IEEE journal in 2002),[29] while others are based on shifts in technology. Wikipedia itself has been noted for creating its own version of the console generations that differ from academic sources.[24] The discrepancies between how consoles are grouped into generations and how these generations are named have caused confusion when trying to compare shifts in the video game marketplace compared to other consumer markets.[24] Kemerer et al. (2017)[24] provide a comparative analysis of these different generations through systems released up to 2010 as shown below.

Console generation timeline

The generations described here use the Wikipedia system of defining console generations, which generally breaks consoles up by technology features whenever possible, and uses the Odyssey and Pong-style home consoles as the first generation, an approach that has generally been adopted and extended by video game journalists.[37][38] In this approach the generation starts with the release of the first console considered to have the generation's defining features, and ends with the last discontinuation of a console in that generation. For example, the third generation is considered to have ended in 2003 with the formal discontinuation of the Nintendo Entertainment System that year. This can create years with overlaps between multiple generations, as shown.

This approach uses the concept of "bit count", generally meaning the word length used by the processors on the console, to define the earlier console generations. More "bits" generally led to improved gameplay, graphics, and audio capabilities.[39] For example, the original Nintendo Entertainment System was 8-bit, while the Super Nintendo Entertainment System was 16-bit. Bits were commonly used in console marketing, starting with the TurboGrafx 16, which had an 8-bit central processor but included a 16-bit graphical processing unit. NEC, the console's manufacturer, marketed the TurboGrafx 16 as a "16-bit" console, supposedly superior to the "8-bit" NES. Other advertisers followed suit, creating a period known as the "bit wars" that lasted through the fifth generation, where console manufactures tried to outsell each other based on the bit-count of their system.[40]

The bit wars essentially ended after the fifth generation, although some sixth-generation consoles like the PlayStation 2 were marketed as "128-bit". Modern game consoles, like essentially all modern computers, are 64-bit. Though the bit terminology fell out of use, older consoles are strongly associated with their bit-count, and the earlier generations gained alternate names based on the dominant bit-count of the major systems of that era. For example, the third generation can be called the 8-bit generation.[40]

Later console generations are based on groupings of release dates rather than common hardware as base hardware configurations between consoles have greatly diverged, generally following trends in generation definition given by video game and mainstream journalism. Handheld consoles and other gaming systems and innovations are frequently grouped within the release years associated with the home console generations; for example the growth of digital distribution is associated with the seventh generation.[25][41]

Console history timeline by generation

The development of video game consoles primarily follows the history of video gaming in the North American and Japanese markets. Few other markets saw any significant console development on their own, such as in Europe where personal computers tended to be favored alongside imports of video game consoles. The video game clone in less-developed markets like China and Russia were not considered here.

First generation (1972–1980)

The first generation of home consoles were generally limited to dedicated consoles with just one or two games pre-built into the console hardware, with a limited means to alter gameplay factors. In the case of the Odyssey, while it did ship with "game cards", these did not have any programmed games on them but instead acted as jumpers to alter the existing circuitry pathway, and did not extend the capabilities of the console.[42] Unlike most other future console generations, the first generation of consoles were typically built in limited runs rather than as an ongoing product line.

The first home console was the Magnavox Odyssey in September 1972 based on Baer's "Brown Box" design.[43] Originally built from discrete transistors, Magnavox transitioned to integrated circuit chips that were inexpensive, and developed a new line of consoles in the Odyssey series from 1975 to 1977. At the same time, Atari had successfully launched Pong as an arcade game in 1972, and began work to make a home console version in late 1974, which they eventually partnered with Sears to the new home Pong console by the 1975 Christmas season. Pong had several technology advantages over the Odyssey, including an internal sound chip and the ability to track score. Coleco developed the first Telstar console in 1976.[44]: 53–59 With Magnavox, Atari and Coleco all vying in the console space by 1976 and further cost reductions in key processing chips from General Instruments, numerous third-party manufacturers entered the console market by 1977 with ball-and-paddle games.[45]: 147 [6][46] This led to market saturation by 1977,[47] and the industry's first market crash.[44]: 81–89 Atari and Coleco attempted to make dedicated consoles with wholly new games to remain competitive, including Atari's Video Pinball series and Coleco's Telstar Arcade, but by this point, the first steps of the market's transition to the second generation of consoles had begun, making these units obsolete near release.[44]: 53–59

The Japanese market for gaming consoles followed a similar path at this point. Nintendo had already been a business partner with Magnovox by 1971 and helped to design the early light guns for the console. Dedicated home game consoles in Japan appeared in 1975 with Epoch Co.'s TV Tennis Electrotennis. As in the United States, numerous clones of these dedicated consoles began to appear, most made by the large television manufacturers like Toshiba and Sharp, and these games would be called TV geemu or terebi geemu (TV game) as the designation for "video games" in Japan.[48] Nintendo became a major player when Mitsubishi, having lost their manufacturer Systek due to bankruptcy, turned to the company to help continue to build their Color TV-Game line, which went on to sell about 3 million units across four different units between 1977 and 1980.[48][49][50]

| Console[note 1] | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Magnavox Odyssey | — | 1972 | — | — | 350,000[51] |

| Ping-O-Tronic | — | — | 1974 | — | 1,000,000[note 2] |

| Home Pong series | — | 1975 | — | — | 200,000[52] |

| TV Tennis Electrotennis | 1975 | — | — | — | 20,000[53] |

| Coleco Telstar | — | 1976 | — | — | 1,000,000 |

| Color TV-Game | 1977 | — | — | 1980 | 3,000,000[note 3] |

Second generation (1976–1992)

The second generation of home consoles was distinguished by the introduction of the game cartridge, where the game's code is stored in read-only memory (ROM) within the cartridge. When the cartridge is slotted into the console, the electrical connections allow the main console's processors to read the game's code from the ROM. While ROM cartridges had been used in other computer applications prior, the ROM game cartridge was first implemented in the Fairchild Video Entertainment System (VES) in November 1976.[54][55] Additional consoles during this generation, all which used cartridge-based systems, included the Atari 2600 (known as the Atari Video Computer System (VCS) at launch), the Magnavox Odyssey 2, Mattel Electronics' Intellivision, and the ColecoVision. In addition to consoles, newer processor technology allowed games to support up to 8 colors and up to 3-channel audio effects.[56]

With the introduction of cartridge-based consoles came the need to develop a wide array of games for them. Atari was one of the forefronts in development for its Atari 2600. Atari marketed the console across multiple regions including into Japan,[48] and retained control of all development aspects of the games. Game developments coincided with the Golden age of arcade video games that started in 1978–1979 with the releases of Space Invaders and Asteroids, and home versions of these arcade games were ideal targets. The Atari 2600 version of Space Invaders, released in 1980, was considered the killer app for home video game consoles, helping to quadruple the console's sales that year.[57] Similarly, Coleco had beaten Atari to a key licensing deal with Nintendo to bring Donkey Kong as a pack-in game for the Colecovision, helping to drive its sales.[29]

.jpg.webp)

At the same time, Atari has been acquired by Warner Communications, and internal policies led to the departure of four key programmers David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead, who went and formed Activision. Activision proceeded to develop their own Atari 2600 games as well as games for other systems. Atari attempted legal action to stop this practice but ended up settling out of court, with Activision agreeing to pay royalties but otherwise able to continue game development, making Activision the first third-party game developer.[58] Activision quickly found success and were able to generate US$50 million in revenue from about US$1 million in startup funds within 18 months.[29] Numerous other companies saw Activision's success and jumped into game development to try to make fast money on the rapidly expanding North America video game market. This led to a loss of publishing control and dilution of the game market by the early 1980s.[59] Additionally, in following on the success of Space Invaders, Atari and other companies had remained eager for licensed video game possibilities. Atari had banked heavily on commercial sales of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in 1982, but it was rushed to market and poorly-received, and failed to make Atari's sales estimates. Along with competition from inexpensive home computers, the North American home console market crashed in 1983.[29][60]

For the most part, the 1983 crash signaled the end of this generation as Nintendo's introduction of the Famicom the same year brought the start of the third generation. When Nintendo brought the Famicom to North America under the name "Nintendo Entertainment System", it helped to revitalize the industry, and Atari, now owned by Jack Tramiel, pushed on sales of the previously successful Atari 2600 under new branding to keep the company afloat for many more years while he transitioned the company more towards the personal computer market.[61] The Atari 2600 stayed in production until 1992, marking the end of the second generation.[62]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Fairchild Channel F | 1977 | 1976 | — | 1983 | 250,000 |

| Atari 2600 | 1983 | 1977 | 1978 | 1992 | 30,000,000 |

| Magnavox Odyssey² | 1982 | 1979 | 1978 | 1984 | 2,000,000 |

| Intellivision | 1982 | 1980 | 1982 | 1990 | 3,000,000 |

| ColecoVision | — | 1982 | 1983 | 1985 | 2,000,000 |

| Atari 5200 | — | 1982 | — | 1984 | 1,400,000 |

Handhelds of the second generation

Handheld electronic games had already been introduced on the market, such as Mattel Auto Race in 1977 and Simon in 1978. While not considered video games as lacking the typical video screen element, instead using LED lights as game indicators, they still established a market for portable video games.

The first handheld game console emerged during the second home console generation, using simple LC displays. Early attempts at cartridge-based handheld systems included the Microvision by Milton-Bradley and the Epoch Game Pocket Computer, but neither gained significant traction. Nintendo, on the other hand, introduced its line of Game & Watch portable games, each with a single dedicated game, as its first venture into the video game market. First introduced in 1980, the Game & Watch series ran for over a decade and sold more than 40 million units.[63]

Third generation (1983–2003)

Frequently called the "8-bit generation", the third generation's consoles used 8-bit processors, five audio channels, and more advanced graphics capability including sprites and tiles instead of block-based graphics of the second generation. Further, the third console saw the market dominance shift from the United States to Japan as a result of the 1983 crash.[64]

Both the Sega SG-1000 and the Nintendo Nintendo Entertainment System launched near simultaneously in Japan in 1983.[65] The Famicom, after some initial technical recalls, soon gained traction and became the best selling console in Japan by the end of 1984.[66] By that point Nintendo wanted to bring the console to North America but recognized the faults that the video game crash had caused. It took several steps to redesign the console to make it look less like a game console and rebranded it as the "Nintendo Entertainment System" (NES) for North America to avoid the "video game" label stigma.[67][68] The company also wanted to avoid the loss of publishing control that had occurred both in North America as well as in Asia after the Famicom's release, and created a lockout system that required all game cartridges to be manufactured by Nintendo to include a special chip. If this chip was not present, the console would fail to play the game. This further gave Nintendo direct control on the titles published for the system, rejecting those it felt were too mature.[69][70] The NES launched in North America in 1985, and helped to revitalize the video game market there.[71]

Sega attempted to compete with the NES with its own Master System, released later in 1986 in both the US and Japan, but did not gain traction to compete. Similarly, Atari's attempts to compete with the NES via the Atari 7800 in 1987 failed to knock the NES from its dominant position.[72] The NES remained in production until 2003, when it was discontinued along with its successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[73]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Famicom/NES | 1983 | 1985 | 1986 | 2003 | 61,910,000 |

| Mark III/Master System | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1996 | 13,000,000 |

| Atari 7800 | — | 1986 | 1987 | 1992 | 3,770,000 |

| Atari XEGS | — | 1987 | 1987 | 1992 | 100,000 |

Fourth generation (1987–2004)

The fourth generation of consoles, also known as the "16-bit generation", further advanced core console technology with 16-bit processors, improving the available graphics and audio capabilities of games.[74]

NEC's TurboGrafx-16 (or PC Engine as released in Japan), first released in 1987,[75] is considered the first fourth generation console even though it still had an 8-bit CPU. The console's 16-bit graphics processor gave it capabilities comparable to the other fourth generation systems, and NEC's marketing had pushed the console being an advancement over the NES as a "16-bit" system.[40][76] Both Sega and Nintendo entered the fourth generation with true 16-bit systems in the 1988 Sega Genesis (Mega Drive in Japan) and the 1990 Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES, Super Famicom in Japan). SNK also entered the competition with a modified version of their Neo Geo MVS arcade system into the Neo Geo, released in 1990, which attempted to bridge the gap between arcade and home console systems with the shared use of common game cartridges and memory cards.[77] This generation was notable for the so-called "console wars" between Nintendo and Sega primarily in North America. Sega, to try to challenge Nintendo's dominant position, created the mascot character Sonic the Hedgehog, who exhibited cool personality to appeal to the Western youth in contrast to Nintendo's Mario, and bundled the Genesis with the game of the same name. The strategy succeeded with Sega becoming the dominant player in North America until the mid-1990s.[78]

During this generation, the technology costs of using optical discs in the form of CD-ROMs has dropped sufficiently to make them desirable to be used for shipping computer software, including for video games for personal computers. CD-ROMs offered more storage space than game cartridges and could allow for full-motion video and other detailed audio-video works to be used in games.[29] Console manufacturers adapted by created hardware add-ons to their consoles that could read and play CD-ROMs, including NEC's TurboGrafx-CD add-on (as well as the integrated TurboDuo system) in 1988, and the Sega CD add-on for the Genesis in 1991, and the Neo Geo CD in 1994. Costs of these add-ons were generally high, nearing the same price as the console itself, and with the introduction of disc-based consoles in the fifth generation starting in 1993, these fell by the wayside.[29] Nintendo had initially worked with Sony to develop a similar add-on for the SNES, the Super NES CD-ROM, but just before its introduction, business relationships between Nintendo and Sony broke down, and Sony would take its idea on to develop the fifth generation PlayStation.[79] Additionally, Philips attempted to enter the market with a dedicated CD-ROM format, the CD-i, also released in 1990, that included other uses for the CD-ROM media beyond video games but the console never gained traction.[80]

The fourth generation had a long tail that overlapped with the fifth generation, with the SNES's discontinuation in 2003 marking the end of the generation.[73] To keep their console competitive with the new fifth generation ones, Nintendo took to the use of coprocessors manufactured into the game cartridges to enhance the capabilities of the SNES. This included the Super FX chip, which was first used in the game Star Fox in 1993, generally considered one of the first games to use real-time polygon-based 3D rendering on consoles.[74]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| PC Engine/TurboGrafx-16 | 1987 | 1989 | 1989 | 1994 | 5,800,000 |

| Mega Drive/Genesis | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1997 | 30,750,000 |

| Neo Geo | 1990 | 1991 | 1994 | 1997 | 980,000 |

| Super Famicom/Super NES | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 2003 | 49,100,000 |

| Sega CD/Mega-CD | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1996 | 2,240,000 |

| CD-i | 1992 | 1991 | 1992 | 1998 | 1,000,000 |

| Neo Geo CD | 1994 | 1996 | 1994 | 1997 | 570,000 |

Handhelds of the fourth generation

Nintendo brought its experience from the Game & Watch series to develop the Game Boy system in 1989, with subsequent iterations through the years. The unit included a LCD screen that supported a 4-shade monochrome pixel display, the use of a cartridge-based system, and the means to link up two units to play head-to-head games. One of the early packages included Tetris bundled with the unit, which became the Game Boy's best-selling game and led the unit to dominate handheld sales at the time.[81] The Game Boy also introduced the Kirby franchise worldwide, which became a staple of Nintendo's handheld consoles.

The Atari Lynx was also introduced in 1989 and included a color-LED screen, but its small game library and low battery life failed to make it competitive with the Game Boy.[82][83][84] Both Sega and NEC also attempted to compete with the Game Boy with the Game Gear and the TurboExpress, respectively, both released in 1990. Each were attempts to bring the respective home console games to handheld systems, but struggled against the staying power of the Game Boy.[84][85]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Game Boy | 1989 | 1989 | 1990 | 2003 | 118,690,000[note 1] |

| Atari Lynx | 1990 | 1989 | 1990 | 1995 | 3,000,000 |

| Game Gear | 1990 | 1991 | 1991 | 1997 | 10,620,000 |

| TurboExpress | 1990 | 1991 | — | 1994 | 1,500,000 |

| |||||

Fifth generation (1993–2006)

During this time home computers gained greater prominence as a way of playing video games. The video game console industry nonetheless continued to thrive alongside home computers, due to the advantages of much lower prices, easier portability, circuitry specifically dedicated towards video games, the ability to be played on a television set (which PCs of the time could not do in most cases), and intensive first party software support from manufacturers who were essentially banking their entire future on their consoles.[86]

Besides the shift to 32-bit processors, the fifth generation of consoles also saw most companies excluding Nintendo shift to dedicated optical media formats instead of game cartridges, given their lower cost of production and higher storage capacity.[87] Initial consoles of the fifth generation attempted to capitalize on the potential power of CD-ROMs, which included the 3DO and the Atari Jaguar in 1993.[88] However, early in the cycle, these systems were far more expensive than existing fourth-generation models and has much smaller game libraries.[29] Further, Nintendo's use of co-processors in late SNES games further kept the SNES as one of the best selling systems over new fifth generation ones.[29]

Two of the key consoles of the fifth generation were introduced in 1995: the Sega Saturn, and the Sony PlayStation, both which challenged the SNES' ongoing dominance. While the Saturn sold well, it did have a number of technical flaws, but established Sega for a number of key game series going forward.[89] The PlayStation, in addition to using optical media, also introduced the use of memory cards as to save the state of a game. Though memory cards had been used by Neo Geo to allow players to transfer game information between home and arcade systems, the PlayStation's approach allowed games to have much longer gameplay and narrative elements, leading to highly-successful role-playing games like Final Fantasy VII.[29] By 1996, the PlayStation became the best-selling console over the GBA.[29]

Nintendo released their next console, the Nintendo 64 in late 1996. Unlike other fifth generation units, it still used game cartridges, as Nintendo believed the load-time advantages of cartridges over CD-ROMs was still essential, as well as their ability to continue to use lockout mechanisms to protect copyrights.[90][91] The system also included support for memory cards as well, and Nintendo developed a strong library of first-party titles for the game, including Wave Race 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time that helped to drive its sales. While the Nintendo 64 did not match the PlayStation's sales, it kept Nintendo a key competitor in the home console market alongside Sony and Sega.[29]

As with the transition from the fourth to fifth generation, the fifth generation has a long overlap with the sixth console generation, with the PlayStation remaining in production until 2006.[92]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| FM Towns Marty | 1993 | — | — | 1995 | 45,000 |

| Amiga CD32 | — | 1994 | 1993 | 1994 | 100,000 |

| Atari Jaguar | 1994 | 1993 | 1994 | 1996 | 250,000 |

| 3DO | 1994 | 1993 | 1994 | 1996 | 2,000,000 |

| PC-FX | 1994 | — | — | 1998 | 400,000 |

| Sega 32X | 1994 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 665,000 |

| Sega Saturn | 1994 | 1995 | 1995 | 2000 | 9,260,000 |

| PlayStation | 1994 | 1995 | 1995 | 2006 | 102,490,000 |

| Nintendo 64 | 1996 | 1996 | 1997 | 2002 | 32,930,000 |

| Apple Pippin | 1996 | 1996 | — | 1997 | 42,000 |

Handhelds of the fifth generation

Nintendo released the Virtual Boy, an early attempt at virtual reality, in 1995. The unit required the player to play a game through a stereoscopic viewerfinder, which was awkward and difficult, and did not lend well to portable gaming.[93][94][95] Nintendo instead returned to focus on incremental improvements to the Game Boy, including the Game Boy Pocket[96][97] and the Game Boy Color.[98]

Sega also released the Genesis Nomad, a handheld unit that played Sega Genesis games, in 1995 in North America only.[99][100] The unit had been developed through Sega of America with little oversight from Sega's main headquarters, and as Sega moved forward, the company as a whole decided to put more focus on the Sega Saturn to stay competitive and drop support for all other ongoing systems, including the Nomad.[101][102][103]

Despite Nintendo's domination of handheld console market, some competing consoles such as Neo Geo Pocket, WonderSwan, Neo Geo Pocket Color, and WonderSwan Color appeared in the late 1990s and discontinued several years later after their appearance in handheld console market.

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Virtual Boy | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1996 | 770,000 |

| Genesis Nomad | — | 1995 | — | 1999 | Unknown |

| Game Boy Pocket | 1996 | 1996 | 1996 | Unknown | Unknown[note 1] |

| Game.com | — | 1997 | 1997 | 2000 | >300,000 |

| Game Boy Light | 1998 | — | — | Unknown | Unknown[note 1] |

| Game Boy Color | 1998 | 1998 | 1998 | 2003 | Unknown[note 1] |

| Neo Geo Pocket | 1998 | — | — | 1999 | Unknown |

| WonderSwan | 1999 | — | — | 1999 | 1,550,000 |

| Neo Geo Pocket Color | 1999 | 1999 | 1999 | 2001 | Unknown |

| WonderSwan Color | 2000 | — | — | 2000 | 1,100,000 |

Sixth generation (1998–2013)

By the sixth generation, console technology began to catch up to performance of personal computers of the time, and the use of bits as their selling point fell by the wayside. The console manufactures focused on the individual strengths of their game libraries as marketing instead. The consoles of the sixth generation saw further adoption of optical media, expanding into the DVD format for even greater data storage capacity, additional internal storage solutions to function as memory cards, as well as adding support either directly or through add-ons to connect to the Internet for online gameplay.[104] Consoles began to move towards a convergence of features of other electronic living room devices and moving away from single-feature systems.[105]

By this point, there were only three major players in the market: Sega, Sony, and Nintendo. Sega got an early lead with the Dreamcast first released in Japan in 1998.[106] It was the first home console to include a modem to allow players to connect to the Sega network and play online games.[29] However, Sega found several technical issues that had to be resolved before its Western launch in 1999.[107][108][109] Though its Western release was more successful than in Japan,[110] the console was soon outperformed by Sony's PlayStation 2 released in 2000. The PlayStation 2 was the first console to add support for DVD playback in addition to CD-ROM, as well as maintaining backward compatibility with games from the PlayStation library, which helped to draw consumers that remained on the long-tail of the PlayStation.[29] While other consoles of the sixth generation had not anticipated this step, the PlayStation 2's introduction of backwards compatibility became a major design consideration of future generations.[111] Along with a strong game library, the PlayStation 2 went on to sell 155 million units before it was discontinued in 2013,[112] and as of 2020, remains the best selling home console of all time.[113][114] Unable to compete with Sony, Sega discontinued the Dreamcast in 2001 and left the hardware market, instead focusing on its software properties.[29] Nintendo's entry in the sixth generation was the GameCube in 2001, its first system to use optical discs based on the miniDVD format. A special Game Boy Player attachment allowed the GameCube to use any of the Game Boy cartridges as well, and adapters were available to allow the console to connect to the Internet via broadband or modem.

At this point Microsoft also entered the console market with its first Xbox system, released in 2001. Microsoft considered the PlayStation 2's success as a threat to the personal computer in the living room space, and had developed the Xbox to compete. As such, the Xbox was designed based more on Microsoft's experience from personal computers, using an operating system built out from its Microsoft Windows and DirectX features, utilizing a hard disk for save game store, built-in Ethernet functionality, and created the first console online service, Xbox Live to support multiplayer games. While the original Xbox had modest sales compared to the PlayStation 2 and was not profitable for the company, Microsoft considered the Xbox to have successfully demonstrated their abilities to participate in the console market.[115]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Dreamcast | 1998 | 1999 | 1999 | 2001 | 9,130,000 |

| PlayStation 2 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2013 | 155,000,000 |

| GameCube | 2001 | 2001 | 2002 | 2007 | 21,740,000 |

| Xbox | 2002 | 2001 | 2002 | 2009 | 24,000,000 |

Handhelds of the sixth generation

Nintendo continued to refine its Game Boy design with the Game Boy Advance in 2001, including its Game Boy Advance SP in 2003 and Game Boy Micro in 2005, all with the ability to link to the GameCube to extend the functionality of certain games. Also introduced were the Neo Geo Pocket Color in 1998 and Bandai's WonderSwan Color, launched in Japan in 1999. South Korean company Game Park introduced its GP32 handheld in 2001, and with it came the dawn of open source handheld consoles.[116]

During the sixth generation, a new type of market for gaming came from the growing mobile phone arena, where advanced smart phones and other portable devices could be loaded with games. Nokia's N-Gage was one of the first devices marketed as a mobile phone and game system, first released in 2003 and later redesigned as the N-Gage QD.

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Game Boy Advance | 2001 | 2001 | 2001 | 2010 | 81,510,000 |

| N-Gage | — | 2003 | 2003 | 2005 | 3,000,000 |

Seventh generation (2005–2017)

Video game consoles had become an important part of the global IT infrastructure by the mid-2000s. It was estimated that video game consoles represented 25% of the world's general-purpose computational power in the year 2007.[117]

By the seventh generation, Sony, Microsoft, and Nintendo had all developed consoles designed to interface with the Internet, adding networking support for either wired and wireless connections, online services to support multiplayer games, digital storefronts for digital purchases of games, and both internal storage and support for external storage on the console for these games. With the start and transition to the HD-era, these consoles also added support for digital television resolutions through HDMI interfaces, but as the generation occurred in the midst of the High-definition optical disc format war between Blu-ray and HD-DVD, a standard for high-definition playback was yet to be fixed. A further innovation came by the use of motion controllers, either built into the console or offered as an add-on afterwards. Consoles in this generation started using custom CPUs based on the PowerPC instruction set, and were increasingly sharing similarities with the personal computer in game development, although with challenges due to the more complex nature of porting between the differences in architectures.

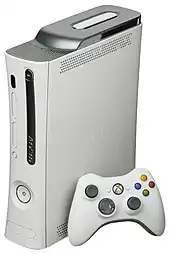

Microsoft entered the seventh generation first with the Xbox 360 in 2005.[118] The Xbox 360 saw several hardware revisions over its lifetime which became a standard practice for Microsoft going forward; these revisions offered different features such as a larger internal hard drive or a fast processor at a higher price point. As shipped, the Xbox 360 supported DVD discs and Microsoft had opted to support the HD-DVD format with an add-on for playback of HD-DVD films. However, this format ended up as deprecated compared to Blu-ray. The Xbox 360 was backward compatible with about half of the original Xbox library. Through its lifetime, the Xbox 360 was troubled by a consistent hardware fault known as "the Red Ring of Death" (RROD), and Microsoft spent over $1 billion correcting the problem.[119]

Sony's PlayStation 3 was released in 2006. The PlayStation 3 represented a shift of the internal hardware from Sony's custom Emotion Engine to a PowerPC-based system. Initial PlayStation 3 units shipped with a special Emotion Engine daughterboard that allowed for backwards compatibility of PlayStation 2 games, but later revisions of the unit removed this, leaving only software-based emulation for PlayStation games available. Sony banked on the Blu-ray format, which was included from the start, and partially helped spur the adoption of Blu-Ray as the favoured format for high-definition optical media.[120] With the PlayStation 3, Sony introduced the PlayStation Network for its online services and storefront. While the system would initially have a slow start in the market in part, due to its high price, complex game development environment and initial lack of quality games, the PlayStation 3 eventually became more well received over time following gradual price cuts, improved marketing campaigns, new hardware revisions particularly the Slim models, and key critically acclaimed exclusives.

Nintendo introduced the Wii in 2006 around the same time as the PlayStation 3. Nintendo lacked the same manufacturing capabilities and relationships with major hardware supplies as Sony and Microsoft,[121] and to compete, diverged on a feature-for-feature approach and instead developed the Wii around the novel use of motion controls in the Wii Remote. This "blue ocean strategy", releasing a product where there was no competition, was considered part of the unit's success,[122] and which drove Microsoft and Sony to develop their own motion control accessors to compete. Nintendo provided various online services that the Wii could connect to, including the Virtual Console where players could purchase emulated games from Nintendo's past consoles as well as games for the Wii. The Wii used regular sized DVDs for its game medium but also directly supported GameCube discs. The Wii was generally considered a surprising success that many developers had initially overlooked.[123][124][125]

The seventh generation concluded with the discontinuation of the PlayStation 3 in 2017.[126]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Xbox 360 | 2005 | 2005 | 2005 | 2016 | 84,700,000 |

| PlayStation 3 | 2006 | 2006 | 2007 | 2017 | 87,400,000 |

| Wii | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 2017 | 101,630,000 |

Handhelds of the seventh generation

Nintendo introduced the new Nintendo DS system in 2004, a game cartridge-based unit that support two screens including one being touch-sensitive. The DS also included built-in wireless connectivity to the Internet to purchase new DS games or Virtual Console titles, as well as the ability to connect to each other or to a Wii system in an ad hoc manner for certain multiplayer titles.[127] Sony entered the handheld market in 2004 with the PlayStation Portable (PSP), with a reduced design based on the PlayStation 3. Like the DS, the PSP also supported wireless connectivity to the Internet to download new games, and ad hoc connectivity to other PSP or to a PlayStation 3. The PSP used a new format called Universal Media Disc (UMD) for game and other media.[128][129][130]

Nokia revived its N-Gage platform in the form of a service for selected S60 devices. This new service launched on April 3, 2008.[131] Other less-popular handheld systems released during this generation include the Gizmondo (launched on March 19, 2005, and discontinued in February 2006) and the GP2X (launched on November 10, 2005, and discontinued in August 2008). The GP2X Wiz, Pandora, and Gizmondo 2 were scheduled for release in 2009.

Another aspect of the seventh generation was the beginning of direct competition between dedicated handheld video game devices, and increasingly powerful PDA/cell phone devices such as the iPhone and iPod Touch, and the latter being aggressively marketed for gaming purposes. Simple games such as Tetris and Solitaire had existed for PDA devices since their introduction, but by 2009 PDAs and phones had grown sufficiently powerful to where complex graphical games could be implemented, with the advantage of distribution over wireless broadband. Apple had launched its App Store in 2008 that allowed developers to publish and sell games for iPhones and similar devices, beginning the rise of mobile gaming.

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Nintendo DS | 2004 | 2004 | 2005 | 2013 | 154,020,000 |

| PlayStation Portable | 2004 | 2005 | 2005 | 2014 | 82,000,000 |

Other seventh generation hardware

Based on the success of the Wii Remote controller, both Microsoft and Sony released similar motion detection controllers for their consoles. Microsoft introduced the Kinect motion controller device for the Xbox 360, which served as both a camera, microphone, and motion sensor for numerous games. Sony released the PlayStation Move, a system consisting of a camera and lit handheld controllers, which worked with its PlayStation 3.

Eighth generation (2012–present)

Aside from the usual hardware enhancements, consoles of the eighth generation focus on further integration with other media and increased connectivity.[134] Consoles at this point had also standardized on CPUs using the x86 instruction set, the same as in personal computers, and there was a convergence of the individual hardware components between consoles and personal computers, making the porting of games between these systems much easier. Later hardware improvements pushed for higher frame rates at up to 4K resolutions.[135] Digital distribution increased in popularity, while the addition and improvements to remote play capabilities became standard, and second screen experiences via companion apps added more interactivity to games.[136]

The Wii U, introduced in 2012, was considered by Nintendo to be a successor to the Wii but geared to more serious players. The console supported backward compatibility with the Wii, including its motion controls, and introduced the Wii U GamePad, a tablet/controller hybrid that acted as a second screen. Nintendo further refined its network offerings to develop the Nintendo Network service to combine storefront and online connectivity services. The Wii U did not sell as well as Nintendo had planned, as they found people mistook the GamePad to be a tablet they could take with them away from the console, and the console struggled to draw the third-party developers as the Wii had.[137]

Both the PlayStation 4 and Xbox One came out in 2013. Both were similar improvements over the previous generation's respective consoles, providing more computational power to support up to 60 frames per second at 1080p resolutions for some games. Each unit also saw a similar set of revisions and repackaging to develop high- and low-end cost versions. In the case of the Xbox One, the console's initial launch had included the Kinect device but this became highly controversial in terms of potential privacy violations and lack of developer support, and by its mid-generation refresh, the Kinect had been dropped and discontinued as a game device.[138] Both consoles eventually released upgraded hardware during their mid-cycle refresh, with Sony releasing the PlayStation 4 Pro and Microsoft releasing the Xbox One X, which allowed for higher frame rates and up to 4K resolution,[139][140] in addition to Slim models, marking a departure from previous generations, while adding considerable longevity to this generation cycle.

Later in the eighth generation, Nintendo released the Nintendo Switch in 2017. The Switch is considered the first hybrid game console. It uses a special CPU/GPU combination that can run at different clock frequencies depending on how it is used. It can be placed into a special docking unit that is hooked to a television and a permanent power supply, allowing faster clock frequencies to be used to be played at higher resolutions and frame rates, and thus more comparable to a home console. Alternatively, it can be removed and used either with the attached Joy-Con controllers as a handheld unit, or can be even played as a tablet-like system via its touchscreen. In these modes, the CPU/GPU run at lower clock speeds to conserve battery power, and the graphics are not as robust as in the docked version. A larger suite of online services was removed through the Nintendo Switch Online subscription, including several free NES and SNES titles, replacing the past Virtual Console system. The Switch was designed to addressed many of the hardware and marketing faults around the Wii U's launch, and has become one of the company's fastest-selling consoles after the Wii.[141]

Game systems in the eighth generation also faced increasing competition from mobile device platforms such as Apple's iOS and Google's Android operating systems. Smartphone ownership was estimated to reach roughly a quarter of the world's population by the end of 2014.[142] The proliferation of low-cost games for these devices, such as Angry Birds with over 2 billion downloads worldwide,[143] presents a new challenge to classic video game systems. Microconsoles, cheaper stand-alone devices designed to play games from previously established platforms, also increased options for consumers. Many of these projects were spurred on by the use of new crowdfunding techniques through sites such as Kickstarter. Notable competitors include the GamePop, OUYA, GameStick Android-based systems, the PlayStation TV, the NVIDIA SHIELD, the Apple TV and Steam Machines.[144]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Wii U | 2012 | 2012 | 2012 | 2017 | 13,560,000 |

| Nintendo Switch | 2017 | 2017 | 2017 | Active | 125,620,000[note 1] |

| PlayStation 4 | 2014 | 2013 | 2013 | Active | 117,200,000 |

| Xbox One | 2014 | 2013 | 2013 | 2020[145] | 51,000,000[note 2] |

Handhelds of the eighth generation

The Nintendo 3DS released in 2011 expanded on the Nintendo DS design and added support for an autostereoscopic screen to project stereoscopic 3D effects without the use of 3D glasses. The console was otherwise remained backward compatible with all of the DS titles.[146][147][148][149] Sony introduced its PlayStation Vita in 2011, a revised version of the PSP but eliminating the use of external media and focusing on digital acquisition of games, as well as incorporating a touchscreen.[150][151][152][153][154] and was released in Europe and North America on February 22, 2012.[155][156]

As noted above, the Nintendo Switch is a hybrid console, capable of both being used as a home console in its docked mode and as a handheld. The Nintendo Switch Lite revision was released in 2019, which reduced some of the features of the system and its size, including eliminating the ability to dock the unit, making the Switch Lite primarily a handheld system, but otherwise compatible with most of the Switch's library of games.[157][158]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| Nintendo 3DS | 2011 | 2011 | 2011 | 2020[159] | 75,940,000 |

| Nintendo Switch Lite | 2019 | 2019 | 2019 | Active | 13,530,000 |

| PlayStation Vita | 2011 | 2012 | 2012 | 2019 | 15,900,000 |

Other eighth generation hardware

Virtual reality systems appeared during the eighth generation, with three main systems: the PlayStation VR headset that worked with PlayStation 4 hardware, the Oculus Rift and the HTC Vive which ran off a personal computer.

Ninth generation (2020–present)

Both Microsoft and Sony released successors to their home consoles in November 2020. Consoles in this generation also launched with lower-cost models lacking optical disc drives, targeting those who would prefer to purchase games exclusively through digital downloads. Both console families target 4K and 8K resolution televisions at high frame rates, support for real-time ray tracing rendering, 3D spatial audio, variable refresh rates, the use of high-performance solid-state drives (SSD) as internal high-speed memory to make delivering game content much faster than reading from optical disc or standard hard drives, which can eliminate loading times and support in-game streaming. With features that were commonly standard in PCs, and the move to higher performance APUs, consoles in the ninth generation now have capabilities comparable to high-end personal computers, often making cross-platform development easier and more widely available than previously, further converging and blurring the line between video game consoles and personal computers.

Microsoft released the fourth generation of Xbox with the Xbox Series X and Series S on November 10, 2020. The Series X has a base performance target of 60 frames per second at 4K resolution to be four times as powerful as the Xbox One X. One of Microsoft's goals with both units was to assure backward compatibility with all games supported by the Xbox One, including those original Xbox and Xbox 360 titles that are backward compatible with the Xbox One, allowing the Xbox Series X and Series S to support four generations of games.[160][161]

Sony's PlayStation 5 was released on November 12, 2020, and also is a similar performance boost over the PlayStation 4. The PlayStation 5 uses a custom SSD solution with much higher input/output rates that are almost comparable to RAM chip speeds, significantly improving rendering and data streaming speeds. The chip architecture is comparable to the PlayStation 4, allowing backwards compatible with most of the PlayStation 4 library while select games will need chip timing tweaking to make them compatible.[162][163]

In terms of handhelds, Sony has announced no further plans for handhelds after discontinuing the Vita, while Nintendo continues to offer the Nintendo Switch and Switch Lite. The market here still continues to compete with the growing mobile gaming market, but developers have taken advantage of new opportunities in cross-platform play support, in part due to the popularity of Fortnite in 2018, to make games that are compatible on consoles, computers, and mobile devices. Cross platform is now used widely in various games.[164][165] Cloud gaming also is seen as a potential replacement of handheld gaming. While earlier cloud gaming platforms have gone by the wayside, newer approaches including PlayStation Now, Microsoft's xCloud, Google's Stadia and Amazon Luna can deliver computer and console-quality gameplay to nearly any platform including mobile devices, limited by bandwidth quality.[166]

| Console | Introduced | Discontinued | Units Sold | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | North America | Europe | |||

| PlayStation 5 | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | Active | 10,000,000[167] |

| Xbox Series X and Series S | 2020 | 2020 | 2020 | Active | ca. 6,500,000[168][note 1] |

| |||||

Console sales

Below is a timeline of each generation with the top three home video consoles of each generation based on worldwide sales.

# | Current | A current generation console being manufactured and sold on the market. |

† | First place | Home console with the highest sales of its generation. |

‡ | Second place | Home console with the second highest sales of its generation. |

◁ | Third place | Home console with the third highest sales of its generation. |

| Remaining places | Manufacturer released a home console but it was not one of the top three best selling home consoles of its generation. | |

| No entry | Manufacturer did not release a home console. |

| Manufacturer | Generation | Ref(s) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (1972–1980) |

Second (1976–1992) |

Third (1983–2003) |

Fourth (1987–2004) |

Fifth (1993–2006) |

Sixth (1998–2013) |

Seventh (2005–2017) |

Eighth (2012–present) |

Ninth (2020–present) | ||

| Atari | Home Pong (150,000) |

Atari 2600 † (30 million)[note 1] |

Atari 7800 ◁ (1 million)[note 2] |

Atari Jaguar (250,000) |

Atari VCS ‡# (10,000+) |

[note 3] | ||||

| Coleco | Telstar ‡ (1 million) |

ColecoVision ◁ (2+ million) |

[note 4] | |||||||

| Nintendo | Color TV-Game series † (3 million) |

NES † (61.91 million) |

Super NES † (49.1 million) |

Nintendo 64 ‡ (32.93 million) |

GameCube ◁ (21.74 million) |

Wii † (101.63 million) |

Nintendo Switch †# (125.62 million)[181][note 5] |

[note 6] | ||

| Magnavox/ Philips |

Odyssey ◁ (330,000) |

Odyssey² (2 million) |

Videopac + G7400 (N/A) |

CD-i (570,000) |

[note 7] | |||||

| Mattel | Intellivision ‡ (3 million) |

HyperScan (N/A) |

[note 8] | |||||||

| Sega | Master System ‡ (10–13 million)[note 9] |

Sega Genesis ‡ (33.75 million) |

Sega Saturn ◁ (9.26 million) |

Dreamcast (9.13 million) |

[note 10] | |||||

| NEC | TurboGrafx-16 ◁ (10 million) |

PC-FX (100,000) |

[note 11] | |||||||

| SNK | Neo Geo AES (1.18 million[cn 1]) |

Neo Geo X (N/A) |

[note 12] | |||||||

| Sony | PlayStation † (102.49 million) |

PlayStation 2 † (>155 million) |

PlayStation 3 ‡ (>87.4 million) |

PlayStation 4‡ # (117.2 million[206] |

PlayStation 5 †# (30 million) |

[note 13] | ||||

| Microsoft | Xbox ‡ (>24 million) |

Xbox 360 ◁ (>84 million) |

Xbox One ◁ (est. 58.6 million[206]) |

Xbox Series X/S ‡ (18.5 million) |

[note 14] | |||||

>Final sales are greater than the reported figure. See notes.

Notes

- ↑ The Atari 2600 sold 30 million units during its life-cycle. Atari also released a second home console during the second generation known as the Atari 5200 which sold 1 million units.

- ↑ The Atari 7800 sold 1 million units. Atari also released the Atari XEGS during the third generation which sold 100,000 units.

- ↑ Home Pong sold 150,000 units.[169][170] Atari 2600 sold 30 million,[171] Atari 5200 and Atari 7800 sold 1 million units each[172][173] Atari XEGS sold 100,000 units,[174] the Atari Jaguar sold 250,000 units.[175] The VCS sold over 10,000+[176]

- ↑

- Telestar: Coleco launched Telstar in 1976 and sold a million. Production and delivery issues, and dedicated consoles being replaced by electronic handheld games dramatically reduced sales in 1977. Over a million Telstars were scrapped in 1978, and it cost Coleco $22.3 million that year[177]—almost bankrupting the company.[178]

- ColecoVision: The ColecoVision reached 2 million units sold by the spring of 1984. Console quarterly sales dramatically decreased at this time, but it continued to sell modestly[179][177] with most inventory gone by October 1985.[180]

- ↑ As of September 30, 2020 the Nintendo Switch has sold 68.30 million units.[182] Nintendo also released the Wii U during the eighth generation which sold 13.56 million units during its lifecycle.[182]

- ↑ Color TV-Game series sold 3 million units.[49] NES, Super NES, Nintendo 64, GameCube and Wii sales figures.[183] Wii U and Switch sales figures.[182]

- ↑ Intellivision sold 3 million units.[186]

- ↑ The Master System sold 10–13 million units. Sega also released the SG-1000 during the third generation which sold 160,000 units.

- ↑

- Master System: 10–13 million, not including recent Brazil sales figures.[187][188] Screen Digest wrote in a 1995 publication that the Master System's active installed user base in Western Europe peaked at 6.25 million in 1993. Those countries that peaked are France at 1.6 million, Germany at 700 thousand, the Netherlands at 200 thousand, Spain at 550 thousand, the United Kingdom at 1.35 million, and other Western European countries at 1.4 million. However, Belgium peaked in 1991 with 600 thousand, and Italy in 1992 with 400 thousand. Thus it is estimated approximately 6.8 million units were purchased in this part of Europe.[189] 1 million were sold in Japan as of 1986.[190] 2 million were sold in the United States.[191] 8 million were sold by Tectoy in Brazil as of 2016.[192]

- Sega Genesis: 30.75 million sold by Sega worldwide as of March 1996,[193][194] not including third-party sales. In addition, Tec Toy sold 3 million in Brazil,[195][196] and Majesco Entertainment projected it would sell 1.5 million in the United States.[197]

- Sega Saturn: 9.26 million units sold.[194]

- Dreamcast: 9.13 million units sold.[194][198][199][200]

- ↑ The TurboGrafx-16 was designed by Hudson and manufactured and marketed by NEC.[201] The TurboGrafx-16 managed to sell 10 million units.[202] The PC-FX sold less than 100,000 after a year on sale.[203]

- ↑ Neo Geo: The AES sold 1 million in Japan[204] 180,000 overseas.[205] The Neo Geo CD was released in the same generation as the AES, sold over 570,000[205] The Neo Geo X was made in a partnership with SNK Playmore & Tommo, currently unknown how many units sold

- ↑ PlayStation: Sony corporate data reports 102.49 million units sold as of March 31, 2007.[207] Sony stopped divulging individual platform sales starting with 2012 fiscal reports,[208][209] and continues to sporadically.[210] PlayStation 2: 155 million units sold as of March 31, 2012.[114] It was discontinued worldwide on January 4, 2013.[211] PlayStation 3: Sony corporate data reports 87.4 million sold as of March 31, 2017.[114] PS3 shipments to Japanese retailers, the last country Sony was selling units to, ceased by May.[212] PlayStation 4: Sony corporate data reports 106 million units sold as of December 31, 2019.[114]

- ↑ Xbox: More than 24 million units sold as of May 10, 2006.[213] Xbox 360: Sold 84 million as of June 2014.[214] Production ended in 2016.[215] Xbox One: Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella unveiled at a December 3, 2014 shareholder presentation that 10 million units were sold.[216] Microsoft announced in October 2015 that individual platform sales in their fiscal reports will no longer be disclosed. The company shifted focus to the amount of active users on Xbox Live as its "primary metric of success".[217] International Data Corporation estimated 46.9 million sold worldwide through the second quarter of 2019.[218]

References

- ↑ "The First Video Game". Brookhaven National Laboratory, U.S. Dept. of Energy. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ↑ Graetz, Martin (August 1981). "The origin of Spacewar". Creative Computing. Vol. 6, no. 8. pp. 56–67. ISSN 0097-8140. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (December 11, 2011). "Computer Space and the Dawn of the Arcade Video Game". Technologizer. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ Baer, Ralph H. (2005). Videogames: In The Beginning. Rolenta Press. pp. 52–59. ISBN 978-0-9643848-1-1.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001). "Chapter 4: And Then There Was Pong". Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- 1 2 Pitre, Boisy G.; Loguidice, Bill (2013-12-10). CoCo: The Colorful History of Tandy's Underdog Computer. CRC Press. p. 11. ISBN 9781466592483.

- ↑ Steinbock, Dan; Johnny L. Wilson (January 28, 2007). The Mobile Revolution. Kogan Page. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7494-4850-9.

- 1 2 Demaria, Rusel; Johnny L. Wilson (2002). High Score! The Illustrated History of Video games. McGraw-Hill. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-07-222428-3.

- ↑ "Optoelectronics Arrives". Time. Vol. 99, no. 14. April 3, 1972. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010.

- ↑ Morgan, Rik (August 5, 2008). "Interview with Howard Cohen". Handheld Museum. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved October 1, 2009.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games. Prima Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (March 28, 2005). "PSPredecessors". 1up. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Mattel's Football (I) (1977, LED, 9 Volt, Model# 2024)". handheldmuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Mattel Electronics Football". Retroland. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Simon Turns 30". 1up.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- ↑ Rubin, Ross (November 10, 2017). "40 Years Of Simon, The Electronic Game That Never Stops Reinventing Itself". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ↑ Demaria, Rusel; Johnny L. Wilson (2002). High Score! The Illustrated History of Video games. McGraw-Hill. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-07-222428-3.

- ↑ Herman, Leonard (2001). Phoenix: The Rise and Fall Of Video Games. Rolenta Press. p. 42. ISBN 0-9643848-5-X.

- ↑ East, Tom (November 11, 2009). "History Of Nintendo: Game Boy". Official Nintendo Magazine. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2013.

- ↑ Crigger, Lara (March 3, 2007). "The Escapist: Searching for Gunpei Yokoi". Escapistmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (October 9, 1997). "Gunpei Yokoi, Chief Designer Of Game Boy, Is Dead at 56". The New York Times.

- ↑ Sheff, David (1999). Game Over: Press Start to Continue. GamePress. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-9669617-0-6.

- ↑ "Game Boy". A Brief History of Game Console Warfare. BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Kemerer, Chris F.; Dunn, Brian Kimball; Janansefat, Shadi (February 2017). Winners-Take-Some Dynamics in Digital Platform Markets: A Reexamination of the Video Game Console Wars (PDF) (Report). University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-12-09. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- 1 2 Maley, Mike (2019). Video Games and Esports: The Growing World of Gamers. Greenhaven Publishing. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-1534568211.

- ↑ Babb, Jeffry; Terry, Neil; Dana, Kareem (2013). "The Impact Of Platform On Global Video Game Sales". International Business & Economics Research Journal. 12 (10): 1273–1288.

- ↑ Conley, James; Andros, Ed; Chinai, Priti; Lipkowitz, Elise; Perez, David (Spring 2004). "Use of a Game Over: Emulation and the Video Game Industry, A White Paper". Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property. 2 (2): 261.

- ↑ Ding, Yifei; Hicks, Daniel; Ju, Jiandong (July 2011). Competing with your own products: Endogenous planned obsolescence in the video game industry (Report). University of Oklahoma.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Gallager, Scott; Ho Park, Seung (February 2002). "Innovation and Competition in Standard-Based Industries: A Historical Analysis of the U.S. Home Video Game Market". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 49 (1): 67–82. doi:10.1109/17.985749.

- ↑ Prieger, James; Hu, Wei-Min (November 2006). "An Empirical Analysis of Indirect Network Effects in the Home Video Game Market". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.941223. S2CID 44033497.

- ↑ Corts, Kenneth; Lenderman, Mara (March 2009). "Software exclusivity and the scope of indirect network effects in the U.S. home video game market". International Journal of Industrial Organization. 27 (2): 121–136. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2008.08.002.

- ↑ Gretz, Richard (November 2010). "Hardware quality vs. network size in the home video game industry". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 76 (2): 168–183. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.07.007.

- ↑ Gretz, Richard (2010). "Console Price and Software Availability in the Home Video Game Industry". Atlantic Economic Journal. 38: 81–94. doi:10.1007/s11293-009-9209-3. S2CID 153330061.

- ↑ Srinivasan, Arati; Venkatraman, N. (November 2010). "Indirect Network Effects and Platform Dominance in the Video Game Industry: A Network Perspective". IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. 57 (4): 661–673. doi:10.1109/TEM.2009.2037738. S2CID 22380339.

- ↑ Derdenger, Timothy (2014). "Technological tying and the intensity of price competition: An empirical analysis of the video game industry". Quantitative Marketing and Economics. 12 (2): 127–165. doi:10.1007/s11129-014-9143-9. S2CID 13439320.

- ↑ Zhou, Yiyi (November 2011). Bayesian estimation of a dynamic equilibrium model of pricing and entry in two-sided markets: application to video games (Report). CiteSeerX 10.1.1.219.4966.

- ↑ "The 8 Generations of Video Game Consoles". BBC. December 1, 2020. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ↑ Lacina, Dia (November 5, 2020). "The Evolution of Game Console Design—and American Gamers". Wired. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Interview: IBM GEKKO (part II)". 18 December 2001. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved January 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Therrien, Carl; Picard, Martin (April 29, 2015). "Enter the bit wars: A study of video game marketing and platform crafting in the wake of the TurboGrafx-16 launch". New Media & Society. 18 (10): 2323–2339. doi:10.1177/1461444815584333. S2CID 19553739.

- ↑ Nieborg, David B. (2014). "Prolonging the Magic: The political economy of the 7th generation console game". Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture. 8 (1): 47–63. doi:10.7557/23.6155. S2CID 61110165.

- ↑ Snider, Mike (February 27, 2020). "Before Nintendo and Atari: How a black engineer changed the video game industry forever". USA Today. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ↑ Buchanan, Levi (May 31, 2007). "ODYSSEY: 35 YEARS LATER". IGN. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016.Between 1970 and 1972, Magnavox and Baer work together to fully develop the Odyssey. The set release date: May 1972. The era of video games is about to explode.

- 1 2 3 Herman, Leonard (2012). "Ball-and-Paddle Controllers". In Wolf, Mark J.P. (ed.). Before the Crash: Early Video Game History. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0814337226.

- ↑ Wolf, Mark J. P. (2012). Encyclopedia of Video Games: A-L. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313379369.

- ↑ Patterson, Shane (June 17, 2008). "Consoles of the '70s". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ↑ Barton, Matt (2019-05-08). Vintage Games 2.0: An Insider Look at the Most Influential Games of All Time. CRC Press. p. 18. ISBN 9781000000924.

- 1 2 3 Picard, Martin (December 2013). "The Foundation of Geemu: A Brief History of Early Japanese video games". International Journal of Computer Game Research. 13 (2). Archived from the original on June 24, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Sheff, David; Eddy, Andy (1999). Game Over: How Nintendo Zapped an American Industry, Captured Your Dollars, and Enslaved Your Children. GamePress. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-9669617-0-6.

Nintendo entered the home market in Japan with the dramatic unveiling of Color TV-Game 6, which played six versions of light tennis. It was followed by a more powerful sequel, Color TV-Game 15. A million units of each were sold. The engineering team also came up with systems that played a more complex game, called "Blockbuster," as well as a racing game. Half a million units of these were sold.

- ↑ DeMaria, Rusel; Wilson, Johnny L. (2003). High Score!: The Illustrated History of Electronic Games (2 ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 363, 378. ISBN 978-0-07-223172-4.

- ↑ Joyce Bedi (January 2019). "Ralph Baer: An interactive life". Human behavior and emerging technologies. 1 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1002/HBE2.119. ISSN 2578-1863. Wikidata Q98908543.

- ↑ John Booth (27 June 2012). "Timeline: A Look Back at 40 Years of Atari". Wired. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ↑ Fujita, Naoki (March 1999). 「ファミコン」登場前の日本ビデオ・ゲーム産業 ―現代ビデオ・ゲーム産業の形成過程(2)― [Japanese Video Game Industry Before the "Famicom": The Rise of the Modern Video Game Industry (2)]. 經濟論叢 (in Japanese). 163 (3): 69. doi:10.14989/45271. ISSN 0013-0273. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2019 – via Kurenai.

- ↑ Weber, Bruce (April 13, 2011). "Gerald A. Lawson, Video Game Pioneer, Dies at 70". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09.

- ↑ "Channel F | The Dot Eaters". thedoteaters.com. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ↑ "CVGA Disassembled - Second Generation (1976-1984)". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ Kent, Steven (2001). Ultimate History of Video Games. Three Rivers Press. p. 190. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ Beller, Peter (January 15, 2009). "Activision's Unlikely Hero". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Stream of video games is endless". Milwaukee Journal. December 26, 1982. pp. Business 1. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (August 28, 2014). "Greatest Years in Gaming History: 1983". USGamer. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ↑ "The Life and Death of Atari". GamePro. No. 92. IDG. May 1996. p. 20.

- ↑ Patterson, Shane; Brett Elston (June 18, 2008). "Consoles of the '80s". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved April 1, 2011.

- ↑ Rwada, Odel (April 20, 2020). "Game & Watch Turns 40: A Look Back at Nintendo's First Gaming Success". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "CVGA Disassembled - Third Generation (1983-1990)". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ↑ "PC-Engine". PC-Engine. Retrieved January 9, 2018.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.

- ↑ "NES". Icons. Season 4. Episode 5010. December 1, 2005. G4. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

- ↑ "25 Smartest Moments in Gaming". GameSpy. July 21–25, 2003. p. 22. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012.

- ↑ Ramirez, Anthony (December 21, 1989). "The Games Played For Nintendo's Sales". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ↑ Cunningham, Andrew (July 15, 2013). "The NES turns 30: How it began, worked, and saved an industry". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved September 21, 2018.

- ↑ "The Nintendo Threat?". Computer Gaming World. June 1988. p. 50.

- ↑ "COMPANY NEWS; Nintendo Suit by Atari Is Dismissed". The New York Times. May 16, 1992. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- 1 2 Nintendo to end Famicom and Super Famicom production. GameSpot.com (May 30, 2003). Retrieved on August 23, 2013.

- 1 2 "Fourth generation (1987-1999)". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ↑ "PC-Engine". Pc-engine.co.uk. Retrieved December 25, 2017.

- ↑ Sartori, Paul (April 2, 2013). "TurboGrafx-16: the console that time forgot (and why it's worth re-discovering)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ↑ Nicoll, Benjamin (2017). "Bridging the Gap: The Neo Geo, the Media Imaginary, and the Domestication of Arcade Games". Games and Culture. 12 (2): 200–221. doi:10.1177/1555412015590048. S2CID 147981978.

- ↑ Kline, Stephen; Dyer-Witheford, Nick; de Peuter, Greig (2003). "Mortal Kombats: Console Wars and Computer Revolutions 1990–1995". Digital play: the interaction of technology, culture, and marketing. McGill Queen University Press. pp. 128–150. ISBN 077357106X.

- ↑ Robinson, Andy (February 5, 2020). "The Road To PS5: PSOne's Betrayal And Revenge Story". Video Games Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ↑ "Philips CD-i 210/45". The Centre for Computing History. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Kindy, David (July 29, 2019). "Thirty Years Ago, Game Boy Changed the Way America Played Video Games". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ "The Atari Lynx". ataritimes.com. 2006. Archived from the original on August 10, 2006. Retrieved August 20, 2006.

- ↑ Beuscher, Dave. "allgame ( Atari Lynx > Overview )". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

One drawback to the Lynx system is its power consumption. It requires 6 AA batteries, which allow four to five hours of game play. The Nintendo Game Boy provides close to 35 hours use before new batteries are necessary.

- 1 2 Blake Snow (July 30, 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Handhelds of All Time". GamePro.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ↑ Bauscher, Dave. "allgame ( Sega Game Gear > Overview )". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

While this feature is not included on the Game Boy, it does not provide a disadvantage -- the Game Gear only requires 6 AA batteries that only last up to six hours. The Nintendo Game Boy requires 4 AA batteries and is capable of providing up to 90 hours of play.

- ↑ "PCs Versus Consoles". Next Generation. No. 18. June 1996. p. 1.

- ↑ "CVGA Disassembled - Fifth generation (1994-2001)". University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ "Which Game System is the Best?!". Next Generation. No. 12. December 1995. pp. 36–85.

- ↑ Fahs, Travis (April 21, 2009). "IGN Presents the History of Sega". IGN. p. 8. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Nintendo Power August, 1994 – Pak Watch. Nintendo. 1994. p. 108.

- ↑ "Nintendo Ultra 64: The Launch of the Decade?". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine (2): 107–8. November 1995.

- ↑ "PlayStation Cumulative Production Shipments of Hardware". Sony Computer Entertainment. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Introduction by Nintendo". The New York Times. 22 August 1995. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ↑ Boyer, Steven. "A Virtual Failure: Evaluating the Success of Nintendos Virtual Boy." Velvet Light Trap.64 (2009): 23-33. ProQuest Research Library. Web. May 24, 2012.

- ↑ King, Geoff; Krzywinska, Tanya (2006). Tomb Raiders and Space Invaders : Videogame Forms and Contexts.

- ↑ "The Incredible Shrinking Game Boy Pocket". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 84. Ziff Davis. July 1996. p. 16.

- ↑ "Pocket Cool". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 89. Ziff Davis. December 1996. p. 204.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Game Console Warfare: Game Boy". BusinessWeek. McGraw-Hill. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- 1 2 Snow, Blake (July 30, 2007). "The 10 Worst-Selling Handhelds of All Time". GamePro. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Sega's 16-Bit Hand-Held Now Named Nomad". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 73. Sendai Publishing. August 1995. p. 27.

- ↑ Horowitz, Ken (February 7, 2013). "Interview: Joe Miller". Sega-16. Archived from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ↑ Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 508, 531. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7.

- ↑ Retro Gamer staff. "Retroinspection: Sega Nomad". Retro Gamer. No. 69. pp. 46–53.