| Western Ukraine | |

|---|---|

Regions that are included in the West of Ukraine | |

| Area | |

| • Coordinates | 50°N 26°E / 50°N 26°E |

Map of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia in the 13th/14th century | |

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine (Ukrainian: Західна Україна, romanized: Zakhidna Ukraina or Захід України, Zakhid Ukrainy) refers to the western territories of Ukraine. There is no universally accepted definition of the territory's boundaries, but the contemporary Ukrainian administrative regions (oblasts) of Chernivtsi, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, Ternopil and Zakarpattia (which were part of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire) are typically included. In addition, Volyn and Rivne Oblasts (parts of the territory annexed from the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during its Third Partition) are also usually included. It is less common to include the Khmelnytskyi Oblasts in this category. It includes several historical regions such as Carpathian Ruthenia, Halychyna including Pokuttia (the eastern portion of Eastern Galicia), most of Volhynia, northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region, and Podolia. Western Ukraine is sometimes considered to include areas of eastern Volhynia, Podolia, and the small northern portion of Bessarabia.

The area of Western Ukraine was ruled by various polities, including the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which became part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but also the Principality of Moldavia; it would then variously come under rule of the Austrian Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Second Polish Republic, the Kingdom of Romania, and finally the Soviet Union (via the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic) in 1939 and 1940 following the invasion of Poland and the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, with the borders finalized after the end of World War II. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it became part of the independent Ukrainian state.

Western Ukraine is known for its exceptional natural and cultural heritage, several sites of which are on the List of World Heritage. Architecturally, it includes the fortress of Kamianets, the Old Town of Lviv, the former Residence of Bukovinian and Dalmatian Metropolitans, the Tserkvas, the Khotyn Fortress and the Pochayiv Lavra. Its landscapes and natural sites also represent a major tourist asset for the region, combining the mountain landscapes of the Ukrainian Carpathians and those of the Podolian Upland. These include Mount Hoverla, the highest point in Ukraine, Optymistychna Cave, the largest in Europe, Bukovel Ski Resort, Synevyr National Park, Carpathian National Park or the Uzhanskyi National Nature Park protecting part of the primary forests included in the Carpathian Biosphere Reserve.[6]

The city of Lviv is the main cultural center of the region and was the historical capital of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia. Other important cities are Chernivtsi, Rivne, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil, Lutsk, Khmelnytskyi and Uzhhorod.

History

Western Ukraine, takes its roots from the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, a successor of Kievan Rus' formed in 1199 after the weakening of Kievan Rus' and attacks from the Golden Horde.

Following the 14th century Galicia–Volhynia Wars, most of the region was transferred to the Crown of Poland under Casimir the Great, who received the lands legally by a downward agreement in 1340 after his nephew's death, Bolesław-Jerzy II. The eastern Volhynia and most of Podolia was added to the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania by Lubart.

The territory of Bukovina was part of Moldavia since its formation by voivode Dragoș, who was departed by the Kingdom of Hungary, during the 14th century.

After the 18th century partitions of Poland (Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth), the territory was split between the Habsburg monarchy and the Russian Empire. The modern south-western part of Western Ukraine became the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, after 1804 crownland of the Austrian Empire. Its northern flank with the cities of Lutsk and Rivne was acquired in 1795 by Imperial Russia following the third and final partition of Poland. Throughout its existence Russian Poland was marred with violence and intimidation, beginning with the 1794 massacres, imperial land-theft and the deportations of the November and January Uprisings.[7] By contrast, the Austrian Partition with its Sejm of the Land in the cities of Lviv and Stanyslaviv (Ivano-Frankivsk) was freer politically perhaps because it had a lot less to offer economically.[8] Imperial Austria did not persecute Ukrainian organizations.[9] In 1846, the Austrian government used the peasant uprising to decimate Polish nobles, who were organising an uprising against Austria.[10] In later years, Austria-Hungary de facto encouraged the existence of Ukrainian political organizations in order to counterbalance the influence of Polish culture in Galicia. The southern half of West Ukraine remained under Austrian administration until the collapse of the House of Habsburg at the end of World War One in 1918.[9]

In 1775, following the Russo-Turkish Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, Moldavia lost to the Habsburg monarchy its northwestern part, which became known as Bukovina, and remained under Austrian administration until 1918.

Interbellum and World War II

Following the defeat of Ukrainian People's Republic (1918) in the Soviet–Ukrainian War of 1921, Western Ukraine was partitioned by the Treaty of Riga between Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Soviet Russia acting on behalf of the Soviet Belarus and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic with capital in Kharkiv. The Soviet Union gained control over the entire territory of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic east of the border with Poland.[11] In the Interbellum most of the territory of today's Western Ukraine belonged to the Second Polish Republic. Territories such as Bukovina and Carpatho-Ukraine belonged to Romania and Czechoslovakia, respectively.

At the onset of Operation Barbarossa by Nazi Germany, the region became occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941. The southern half of West Ukraine was incorporated into the semi-colonial Distrikt Galizien (District of Galicia) created on August 1, 1941 (Document No. 1997-PS of July 17, 1941 by Adolf Hitler) with headquarters in Chełm Lubelski, bordering district of General Government to the west. Its northern part (Volhynia) was assigned to the Reichskommissariat Ukraine formed in September 1941. Notably, the District of Galicia was a separate administrative unit from the actual Reichskommissariat Ukraine with capital in Rivne. They were not connected with each other politically for Nazi Germans.[12] The division was administrative and conditional, in his book "From Putyvl to the Carpathian" Sydir Kovpak never mentioned about any border-like divisions. Bukovina was controlled by the Nazi-allied Kingdom of Romania.

Post-War

After the defeat of Germany in World War II, in May 1945 the Soviet Union incorporated all territories of current Western Ukraine into the Ukrainian SSR.[11] Between 1944 and 1946, a population exchange between Poland and Soviet Ukraine occurred in which all ethnic Poles and Jews who had Polish citizenship before September 17, 1939 (date of the Soviet Invasion of Poland) were transferred to post-war Poland and all ethnic Ukrainians to the Ukrainian SSR, in accordance with the resolutions of the Yalta and Tehran conferences and the plans about the new Poland–Ukraine border.[13]

Recent history

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russia attacked Ukrainian military facility near the city of Lviv,[14] in Western Ukraine with cruise missiles. Later in March Russia performed missile attacks on oil depots in Lviv,[15] Dubno[16][17] and Lutsk.[18]

Divisions

Western Ukraine includes such lands as Zakarpattia, Volyn, Halychyna (Prykarpattia, Pokuttia), Bukovina, Polissia, and Podillia.

The history of Western Ukraine is closely associated with the history of the following lands:

- Easternmost Bukovina, historical region of Central Europe in official use since 1775, controlled by the Kingdom of Romania after World War I, and half of it ceded to the USSR in 1940 (reconfirmed by Paris Peace Treaties, 1947)

- Eastern Galicia (Ukrainian: Halychyna), once a small kingdom with Lodomeria (1914), province of the Austrian Empire until the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918. See also: crownland of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

- Red Ruthenia since medieval times in the area known today as Eastern Galicia.

- West Ukrainian People's Republic declared in late 1918 until early 1919 and claiming half of Galicia with mostly Polish city dwellers (historical sense).

- Carpatho-Ukraine region within Czechoslovakia (1939) under Hungarian control until the Nazi occupation of Hungary in 1944.

- General Government of Galicia and Bukovina captured from Austria-Hungary during World War I.

- Ținutul Suceava (Kingdom of Romania)

- Volhynia, historic region straddling Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus to the north. The alternate name for the region today is Lodomeria after the city of Volodymyr. See also: Polish unofficial term Kresy (Borderlands, 1918–1939) that includes the West Belarus as well as Volhynia.

- Zakarpattia or Carpathian Ruthenia presently in the Zakarpattia Oblast of western Ukraine.

Administrative and historical divisions

| Administrative region | Area sq km | Population (2001 Census) | Population Estimate (Jan 2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chernivtsi Oblast | 8,097 | 922,817 | 905,264 |

| Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast | 13,927 | 1,409,760 | 1,380,128 |

| Khmelnytskyi Oblast | 20,629 | 1,430,775 | 1,320,171 |

| Lviv Oblast | 21,831 | 2,626,543 | 2,540,938 |

| Rivne Oblast | 20,051 | 1,173,304 | 1,154,256 |

| Ternopil Oblast | 13,824 | 1,142,416 | 1,080,431 |

| Volyn Oblast | 20,144 | 1,060,694 | 1,038,598 |

| Zakarpattia Oblast | 12,753 | 1,258,264 | 1,250,759 |

| Total | 131,256 | 10,101,756 | 9,765,281 |

Cultural characteristics

Differences with rest of Ukraine

"Perhaps, if Ukraine did not have its western regions, with Lviv at the centre, it would be easy to turn the country into another Belarus. But Galichina (Halychyna) and Bukovina, which became part of Soviet Ukraine under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, brought to the country a rebellious and free spirit."

Andrey Kurkov in an opinion piece about Euromaidan on BBC News Online (28 January 2014)[19]

Ukrainian is the dominant language in the region. Back in the schools of the Ukrainian SSR learning Russian was mandatory; currently, in modern Ukraine, in schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, classes in Russian and in other minority languages are offered.[9][20]

In terms of religion, the majority of adherents share the Byzantine Rite of Christianity as in the rest of Ukraine, but due to the region escaping the 1920s and 1930s Soviet persecution, a notably greater church adherence and belief in religion's role in society is present. Due to the complex post-independence religious confrontation of several church groups and their adherents, the historical influence played a key role in shaping the present loyalty of Western Ukraine's faithful. In Galician provinces, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has the strongest following in the country, and the largest share of property and faithful. In the remaining regions: Volhynia, Bukovina and Transcarpathia the Orthodoxy is prevalent. Outside of Western Ukraine the greatest in terms of Church property, clergy, and according to some estimates, faithful, is the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). In the listed regions (and in particular among the Orthodox faithful in Galicia), this position is notably weaker, as the main rivals, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church, have a far greater influence. Within the lands of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest Eastern Catholic Church, priests' children often became priests and married within their social group, establishing a tightly-knit hereditary caste.[21]

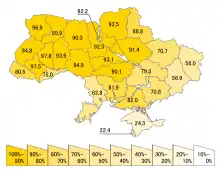

Noticeable cultural differences in the region (compared with the rest of Ukraine especially Southern Ukraine and Eastern Ukraine) are more "negative views" on the Russian language[22][23] and on Joseph Stalin[24] and more "positive views" on Ukrainian nationalism.[25] A higher percentage of voters in Western Ukraine supported Ukrainian independence in the 1991 Ukrainian independence referendum than in the rest of the country.[26][27]

In a poll conducted by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in the first half of February 2014 0.7% of polled in West Ukraine believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5, this study did not include polls in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine.[28]

During elections voters of Western oblasts (provinces) vote mostly for parties (Our Ukraine, Batkivshchyna)[29] and presidential candidates (Viktor Yushchenko, Yulia Tymoshenko) with a pro-Western and state reform platform.[30][31][32] Of the regions of Western Ukraine, Galicia tends to be the most pro-Western and pro-nationalist area. Volhynia's politics are similar, though not as nationalist or as pro-Western as Galicia's. Bukovina-Chernvisti's electoral politics are more mixed and tempered by the region's significant Romanian minority. Finally, Zakarpattia's electoral politics tend to be more competitive, similar to a Central Ukrainian oblast. This is due to the region's distinct historical and cultural identity as well as the significant Hungarian and Romanian minorities. The politics in the region was dominated by such Ukrainian parties as Andriy Baloha's Team, Social Democratic Party of Ukraine (united), Congress of Carpathian Ruthenians led by the Rusyn Orthodox Church bishop Dimitry Sydor and KMKSZ – Hungarian Party in Ukraine.

Demographics

Religion

Religion in western Ukraine (2016)[33]

According to a 2016 survey of religion in Ukraine held by the Razumkov Center, approximately 93% of the population of western Ukraine declared to be believers, while 0.9% declared to non-believers, and 0.2% declared to atheists.

Of the total population, 97.7% declared to be Christians (57.0% Eastern Orthodox, 30.9% members of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, 4.3% simply Christians, 3.9% members of various Protestant churches, and 1.6% Latin Church Catholics), by far more than in all other regions of Ukraine, while 0.2% were Jews. Non-believers and other believers not identifying with any of the listed major religious institutions constituted about 2.1% of the population.[33]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Perfecky, George A. (1973). The Galician-Volynian Chronicle. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. OCLC 902306

- ↑ "Kam'ianets-Podilskyi historical". kampod.name (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 2011-04-30. Retrieved 2011-05-10.

- ↑ Bochenek 1980, p. 93.

- ↑ Welcome to Ukraine: About Kamianets-Podilskyi Archived 2013-05-13 at the Wayback Machine MIBS Travel

- ↑ A trip to historic Kamianets-Podilskyi: crossroads of many cultures Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Roman Woronowycz, Kyiv Press Bureau.

- ↑ UNESCO: Carpathian, July 2011

- ↑ Norman Davies (2005), "Part 2. Rossiya: The Russian Partition", God's Playground. A History of Poland, vol. II: 1795 to the Present, Oxford University Press, pp. 60–82, ISBN 0199253404, archived from the original on February 11, 2023, retrieved January 27, 2014

- ↑ David Crowley (1992), National Style and Nation-state: Design in Poland from the Vernacular Revival to the International Style (Google Print), Manchester University Press ND, 1992, p. 12, ISBN 0-7190-3727-1, archived from the original on 2023-02-11, retrieved 2020-11-21

- 1 2 3 Serhy Yekelchyk Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- ↑ (in Polish) rabacja galicyjska Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine in Internetowa encyklopedia PWN

- 1 2 Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States: 1999 Archived 2023-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, Routledge, 1999, ISBN 1857430581 (page 849)

- ↑ Arne Bewersdorf. "Hans-Adolf Asbach. Eine Nachkriegskarriere" (PDF). Band 19 Essay 5 (in German). Demokratische Geschichte. pp. 1–42. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ↑ ""Переселение белорусов из Польши и Полесская область (1944-1947 гг.)"". 30 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2022-03-11.

- ↑ "Russia strikes Ukraine army base near Poland as it widens attacks". Aljazeera News Agency. 14 March 2022. Archived 2022-03-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The Lviv oil depot was completely destroyed by a Russian missile - the Regional State Administration". Ukrainska Pravda. 27 March 2022. Archived 2022-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Rivne Administration: Oil depot in Dubno razed to the ground after missile strike". Ukrainska Pravda. March 27, 2022. Archived 2022-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Russian rocket hits an oil depot in the Rivne region". Ukrainska Pravda. March 28, 2022. Archived 2022-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Lutsk missile strike: Head of Volyn region shares details". Ukrainska Pravda. March 28, 2022. Archived 2022-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Viewpoint: Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov on the protests Archived 2018-10-11 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (28 January 2014)

- ↑ The Educational System of Ukraine Archived 2020-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Recognition Network, April 2009.

- ↑ Subtelny, Orest (2009). Ukraine: a history (4th ed.). Toronto [u.a.]: University of Toronto Press. pp. 214–219. ISBN 978-1-4426-9728-7. Archived from the original on 2023-02-11. Retrieved 2021-01-11.

- ↑ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012 Archived 2015-07-09 at the Wayback Machine, RATING (25 May 2012)

- ↑ "Poll: Over half of Ukrainians against granting official status to Russian language - Dec. 27, 2012". 27 December 2012. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ↑ (in Ukrainian) Ставлення населення України до постаті Йосипа Сталіна Attitude population Ukraine to the figure of Joseph Stalin Archived 2018-09-17 at the Wayback Machine, Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (1 March 2013)

- ↑ "Who's Afraid of Ukrainian History?" by Timothy D. Snyder, The New York Review of Books (21 September 2010). Archived 2015-10-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ukrainian Nationalism in the 1990s: A Minority Faith by Andrew Wilson, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521574579 (page 128). Archived 2023-02-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ivan Katchanovski. (2009). Terrorists or National Heroes? Politics of the OUN and the UPA in Ukraine Archived 2017-08-08 at the Wayback Machine Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association, Montreal, June 1–3, 2010

- ↑ "How relations between Ukraine and Russia should look like? Public opinion polls' results", Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (4 March 2014). Archived 2017-12-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Центральна виборча комісія України - WWW відображення ІАС "Вибори народних депутатів України 2012" Archived 2012-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

CEC substitues Tymoshenko, Lutsenko in voting papers Archived 2014-08-13 at the Wayback Machine - ↑ Communist and Post-Communist Parties in Europe Archived 2023-02-11 at the Wayback Machine by Uwe Backes and Patrick Moreau, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008, ISBN 978-3-525-36912-8 (page 396)

- ↑ Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle? Archived 2017-10-14 at the Wayback Machine, openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)

- ↑ Kuzio, Taras (17 October 2012). "Eight Reasons Why Ukraine's Party of Regions Will Win the 2012 Elections". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 2016-03-28.

Kuzio, Taras (5 October 2007). "UKRAINE: Yushchenko needs Tymoshenko as ally again" (PDF). Oxford Analytica. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15. - 1 2 РЕЛІГІЯ, ЦЕРКВА, СУСПІЛЬСТВО І ДЕРЖАВА: ДВА РОКИ ПІСЛЯ МАЙДАНУ (Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan) Archived 2017-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, 2016 report by Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches. pp. 27-29.

External links

Western Ukraine travel guide from Wikivoyage

Western Ukraine travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Western Ukraine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Western Ukraine at Wikimedia Commons